Liberty During Evaluation: Japan's Supreme Court on Revoking Pre-Hearing Psychiatric Commitment Orders

Date of Decision: August 7, 2009, Supreme Court of Japan (Third Petty Bench)

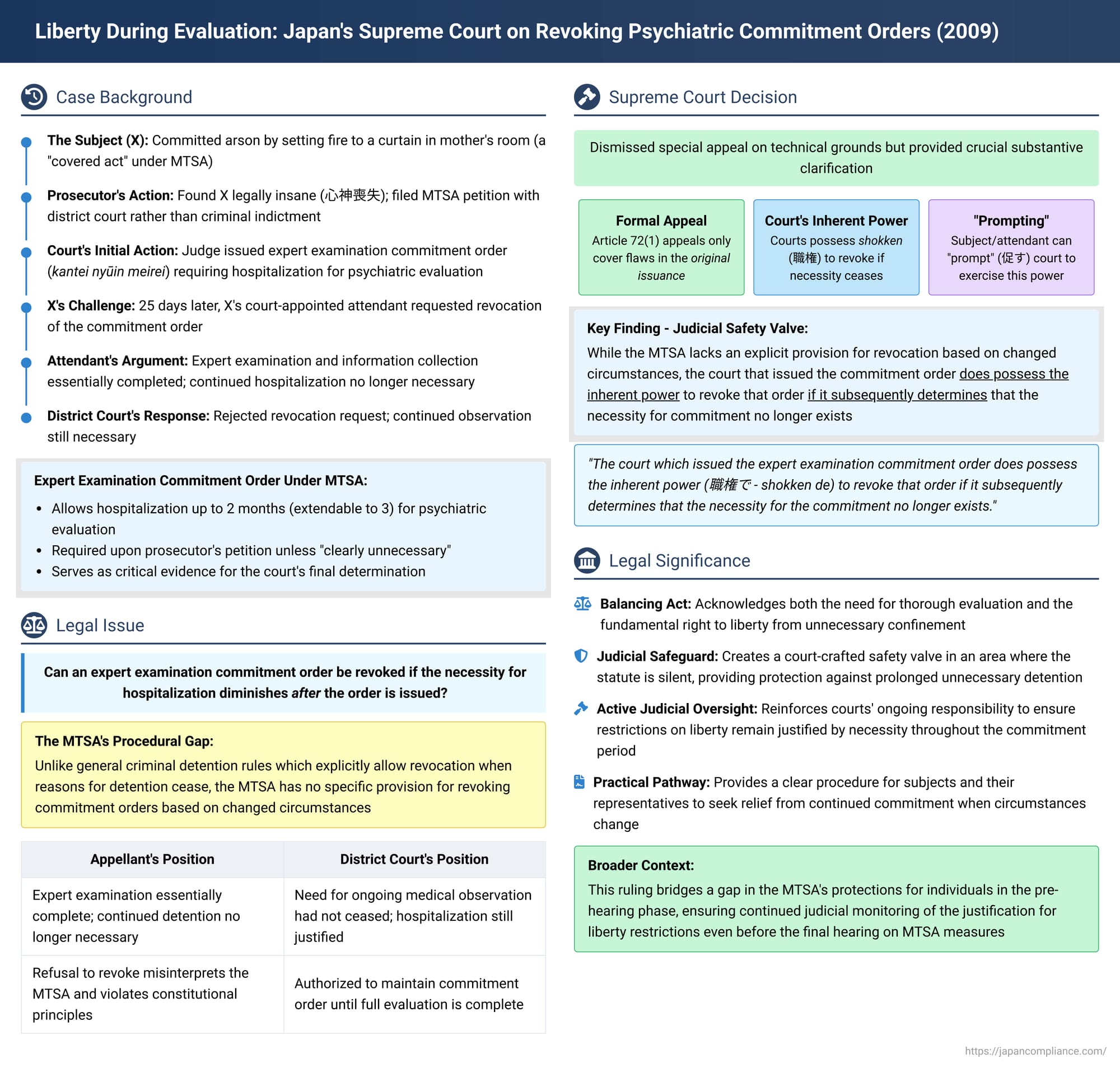

Japan's "Act for Medical Treatment and Supervision of Persons Who Have Caused Serious Harm to Others in a State of Insanity or Diminished Capacity" (commonly known as the 医療観察法 - Iryō Kansatsu Hō, or the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act, MTSA) establishes a specialized legal and medical framework for individuals who commit serious offenses while mentally incapacitated. A critical early step in this process is often an "expert examination commitment order" (kantei nyūin meirei), which mandates the individual's hospitalization for psychiatric evaluation. A Supreme Court decision on August 7, 2009, addressed the important question of what legal recourse is available if the necessity for such a commitment appears to diminish after the order has been issued but before the examination period concludes.

The Medical Treatment and Supervision Act (MTSA): A Brief Overview

The MTSA, enacted to bridge a gap between the criminal justice and mental health systems, aims to provide "continuous and appropriate medical care, and the observation and guidance necessary to secure it, thereby improving their medical condition, preventing the recurrence of similar acts, and promoting their social reintegration" (Article 1). It applies to individuals who have committed specified serious "covered acts" (such as arson, homicide, robbery, serious assault, or sexual offenses) but were found to be in a state of legal insanity (shinshin sōshitsu) or diminished capacity (shinshin kōjaku) at the time.

The process typically begins when a public prosecutor, after deciding not to indict an individual for a covered act due to their mental state (or if they are acquitted on such grounds), files a petition with a district court. This court, comprising a judge and lay mental health assessors (精神保健審判員 - seishin hoken shinpan'in), then holds a hearing to determine the necessity and type of measures under the MTSA. The court can order inpatient treatment, outpatient treatment, or determine that no treatment under the Act is necessary (Article 42, paragraph 1).

A crucial precursor to this hearing is often the Expert Examination Commitment Order (鑑定入院命令 - kantei nyūin meirei). Under Article 34, paragraph 1 of the MTSA, upon receiving the prosecutor's petition, a judge must issue this order—unless it is "clearly unnecessary" to provide medical treatment under the Act. This order mandates the individual's hospitalization for a period, generally not exceeding two months (extendable to three months in necessary cases, Article 34, paragraph 3), for two main purposes:

- Expert Psychiatric Examination (鑑定 - kantei): To determine if the person has a mental disorder and whether they require treatment under the MTSA to improve their condition and prevent future harm (Article 37, paragraph 1). This examination considers various factors, including past medical history, current and past symptoms, the nature of the committed act, and future prognosis.

- Medical Observation (医療的観察 - iryō-teki kansatsu): Ongoing, daily observation of the individual's behavior, symptoms, and response to any interim medical interventions from a medical standpoint.

The findings of this expert examination and observation period are vital evidence for the court panel in making its final determination on MTSA measures.

The Case of X: Arson, Insanity, and a Challenge to Continued Commitment

The appellant, X, had committed an act of arson by setting fire to a curtain in his mother's room, with the fire subsequently spreading and damaging parts of the room. The act would typically constitute the serious crime of "arson of an inhabited structure" (Penal Code Article 108).

The public prosecutor investigated X but concluded that X was in a state of legal insanity (shinshin sōshitsu) at the time of the act. Consequently, X was not indicted. Instead, the prosecutor filed a petition with the district court for a hearing under the MTSA, alleging that X had committed a covered act while mentally incapacitated and required treatment under the Act.

Following the prosecutor's petition, a judge of the Kyoto District Court issued an expert examination commitment order against X, mandating his hospitalization for evaluation. Twenty-five days after this order was issued, X's court-appointed attendant (tsukisoinin, a legal representative in MTSA proceedings) filed a request with the District Court to revoke the commitment order. The attendant argued that the necessary expert examination and the collection of information for the social circumstances investigation had essentially been completed, and therefore, the continued necessity for X's involuntary hospitalization had significantly diminished.

The Kyoto District Court, however, rejected this revocation request. It found that the need for X's continued presence in the hospital for the purposes of expert examination and ongoing medical observation had not ceased. X's attendant then lodged a special appeal with the Supreme Court, arguing that the District Court's decision to maintain the commitment order involved a misinterpretation of the MTSA and violated constitutional principles.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (August 7, 2009)

The Supreme Court unanimously dismissed X's special appeal on the technical grounds that the arguments presented (primarily alleging misinterpretation of law and constitutional violations) did not meet the stringent criteria for a special appeal under MTSA Article 72, paragraph 3, and Article 433 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

However, the Court did not stop there. Recognizing the importance of the underlying issue, it exercised its inherent judicial authority (shokken, 職権) to provide a significant clarification on the law concerning the revocation of expert examination commitment orders:

- Limitations of Statutory Appeal (MTSA Article 72, paragraph 1): The Supreme Court first clarified the scope of the formal appeal process available under MTSA Article 72, paragraph 1. This provision allows an appeal against the issuance of an expert examination commitment order. The Court stated that arguments based on circumstances that arise after such an order has been validly issued—for example, a claim that the necessity for the commitment has subsequently disappeared (as argued by X's attendant)—are not valid grounds for a revocation request under this specific statutory appeal route. This implies that Article 72, paragraph 1 is intended to challenge flaws or errors present at the moment the original order was made, not to address subsequent changes in circumstances.

- Court's Inherent Power to Revoke on Its Own Motion (Shokken): Despite this limitation on the formal appeal, the Supreme Court established a crucial alternative. It ruled that the court which issued the expert examination commitment order does possess the inherent power (職権で - shokken de) to revoke that order if it subsequently determines that the necessity for the commitment no longer exists. This could occur, for instance, if the court, after hearing the expert's opinion or based on other emerging information, becomes convinced that medical treatment under the MTSA is "clearly unnecessary" for the individual.

- Prompting the Court to Exercise its Shokken Power: While this power of revocation is discretionary and exercised on the court's own initiative, the Supreme Court further clarified that the subject of the order, their legal guardian, or their court-appointed attendant can "prompt" (促す - unagasu) the court to exercise this discretionary power. This means they can bring new information or arguments to the court's attention, effectively requesting that the court consider revoking the order due to changed circumstances indicating a lack of ongoing necessity.

Discussion: Balancing Evaluative Needs and Individual Liberty

The Supreme Court's decision navigates a delicate balance between the state's need to conduct thorough evaluations under the MTSA and the protection of individual liberty.

- Importance of the Expert Examination: The commitment order facilitates a crucial phase of the MTSA process. The psychiatric examination and continuous medical observation during this period provide essential data for the court panel to make an informed and appropriate final decision regarding long-term treatment and supervision. In this sense, the commitment can serve the subject's interest by ensuring any subsequent treatment order is well-founded.

- Liberty Concerns: Nevertheless, an expert examination commitment order results in involuntary hospitalization, which is a significant deprivation of personal liberty. This occurs before a final judicial determination has been made about the necessity of long-term compulsory treatment under the MTSA.

- Gaps in the MTSA for Pre-Hearing Detainees: Legal commentators have pointed out that the MTSA, while providing various safeguards for individuals under a final treatment order (e.g., regarding communication rights, limitations on physical restraint in Articles 92 and 93), has fewer explicit protections for those under a pre-hearing expert examination commitment order.

- For instance, the Act does not contain a specific provision analogous to Article 87, paragraph 1 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (which allows for the revocation of criminal detention if the reasons or necessity for detention cease). The rationale often given is that the ultimate decision on whether MTSA treatment is necessary is reserved for the main hearing panel. If found unnecessary, the panel will issue a decision to that effect (Article 42, paragraph 1, item (iii)).

- Furthermore, the provision of medical treatment (as distinct from mere observation or examination) during the expert examination commitment period is not explicitly detailed in the MTSA itself, though administrative notices permit treatment that does not conflict with the aims of the examination.

The Supreme Court's "Rescue Measure"

The Supreme Court's clarification regarding the court's inherent shokken power to revoke a commitment order is highly significant. It acts as a crucial, judicially crafted safeguard in an area where the statute itself is relatively silent on post-issuance changes in necessity.

- Addressing a Legislative Lacuna: By recognizing this power, the Court provides a mechanism to ensure that individuals are not subjected to unnecessary or unduly prolonged pre-hearing detention if the grounds for that detention clearly dissipate after the initial order.

- Affirming Judicial Oversight and Minimized Restriction: This ruling reinforces the judiciary's active role in overseeing such commitments and affirms the principle that restrictions on personal liberty, even within the specialized framework of the MTSA, should be minimized and continuously justified by necessity. While the individual or their attendant cannot formally demand revocation based on new circumstances through the standard appeal route of Article 72(1), they can actively bring these new facts to the court's attention to trigger its discretionary review.

Implications for Practice

This decision has important practical implications:

- It provides a clear, albeit non-statutory, pathway for individuals and their representatives to seek relief from an expert examination commitment if they believe its continuation is no longer justified by new developments.

- It encourages courts to remain vigilant and responsive to changes in a subject's condition or the progress of the examination, even after a commitment order has been lawfully issued.

- It underscores the importance for attendants to diligently gather and present any information that might suggest the diminishing necessity of continued commitment to prompt such a discretionary review by the court.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's August 7, 2009, decision, while formally dismissing the special appeal on technical grounds, delivered an important substantive clarification regarding the management of expert examination commitment orders under Japan's Medical Treatment and Supervision Act. By confirming that courts retain an inherent, discretionary power to revoke such orders if the underlying necessity ceases to exist—and that subjects or their representatives can prompt the exercise of this power—the Supreme Court provided a vital, judicially recognized safeguard for individual liberty. This ruling acknowledges the critical balance that must be struck between the requirements of a thorough psychiatric evaluation process for serious cases and the fundamental right of individuals to be free from unnecessary confinement, especially during the often-vulnerable pre-hearing phase of MTSA proceedings.