AI-Generated Copyright Infringement in Japan: Liability for Users, Developers & Platforms Explained

TL;DR

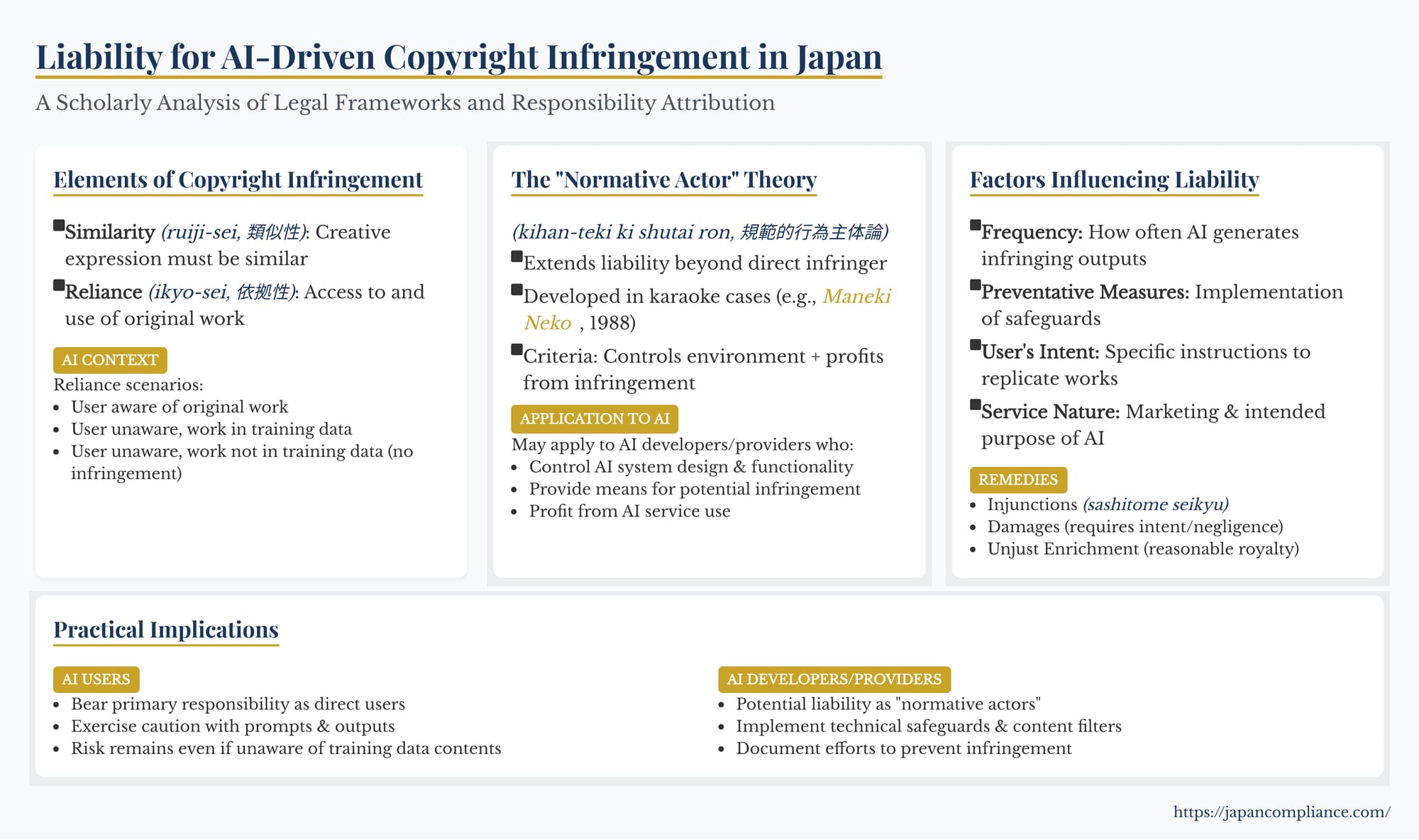

- Direct users of a generative-AI tool are the primary infringers when outputs copy protected works, but intent/negligence determines damages.

- Japan’s unique “normative actor” theory can extend liability to AI developers or service providers who control, profit from and fail to curb infringing outputs.

- Key defences are robust output filters, documented safeguards and clear user policies.

Table of Contents

- Elements of Copyright Infringement in Japan

- Establishing Reliance in the AI Context

- Primary Liability: The AI User

- Extending Liability: The “Normative Actor” Theory

- Factors Influencing Developer/Provider Liability

- Remedies for AI-Driven Infringement

- Comparison with US Secondary Liability Theories

- Conclusion

Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems possess the remarkable ability to create novel content, but this power comes with inherent legal risks. When an AI generates text, images, or music that is substantially similar to existing copyrighted works, who is legally responsible for the potential copyright infringement under Japanese law? Is it the end-user who provided the prompt? The company that developed the AI model? Or the platform that hosts the AI service?

Understanding the potential allocation of liability is crucial for businesses developing, deploying, or utilizing generative AI technologies in connection with the Japanese market. While case law specifically addressing generative AI infringement is still developing, Japan's Copyright Act and established legal principles, including the unique "normative actor" theory, provide a framework for analyzing potential responsibility.

Elements of Copyright Infringement in Japan

To establish copyright infringement under the Japanese Copyright Act, a claimant generally needs to demonstrate two key elements:

- Similarity (類似性 - ruiji-sei): The allegedly infringing work must be similar to the pre-existing copyrighted work. Crucially, this similarity must pertain to the creative expression of thoughts or feelings, not merely the underlying ideas, facts, concepts, or general style. The standard for assessing similarity remains the same whether the work was created by a human or generated with AI assistance – it involves an objective comparison of the expressive features.

- Reliance (依拠性 - ikyo-sei): The creator of the allegedly infringing work must have had access to the original copyrighted work and used it as a basis for their creation. Independent creation, even if resulting in a similar work by chance, does not constitute infringement.

Establishing Reliance in the AI Context

The element of "reliance" becomes particularly complex with generative AI. How can reliance be established when the AI, not the human user, processed the original work during training, and the user might be unaware of the original work's existence?

The Agency for Cultural Affairs' March 2024 "Perspectives Regarding AI and Copyright" (the "Views") outlines several scenarios:

- User Aware of Original Work: If the AI user knew about the existing copyrighted work (e.g., inputted it directly or prompted the AI using specific references to it) and the output is similar, reliance can generally be established based on the user's knowledge and actions, much like in traditional infringement cases.

- User Unaware, Work in Training Data: If the user was unaware of the original work, but that work was included in the AI's training data, reliance is generally presumed. The reasoning is that the AI system itself had "access" to the work during training, and this access is attributed to the generation process initiated by the user. This presumption is potentially rebuttable, but only under specific circumstances where it can be reasonably demonstrated that, due to the AI's architecture or effective output filtering mechanisms, the creative expression of the specific training work could not have influenced the final output. Proving this negative could be challenging.

- User Unaware, Work Not in Training Data: If the user was unaware of the original work, and the work was not part of the AI's training data, then any similarity in the output is considered coincidental. In this case, reliance cannot be established, and there is no copyright infringement.

This framework places significant importance on the composition of the AI's training dataset when the user lacks direct knowledge of the original work.

Primary Liability: The AI User

Generally, the individual or entity who directly uses the generative AI system – providing prompts, selecting outputs, and utilizing the generated content – is considered the primary actor. If the generated output infringes a copyright (i.e., is substantially similar to a protected work based on reliance), the user is typically considered the direct infringer and primarily liable.

However, liability for remedies like damages hinges on the user's mental state. If the user intentionally prompted the AI to replicate a copyrighted work or was negligent in using the AI (e.g., ignoring obvious signs of infringement), they could be liable for damages (Japanese Civil Code, Article 709). If the user acted without intent or negligence – for example, if they were reasonably unaware that the output was infringing or that the underlying work was in the training data – their liability might be limited to injunctive relief (stopping the infringing use) and potentially disgorgement of unjust enrichment (often equivalent to a reasonable royalty), but not compensatory damages.

Extending Liability: The "Normative Actor" Theory

A unique feature of Japanese law that could potentially extend liability beyond the direct user is the "normative actor" theory (規範的行為主体論 - kihan-teki kōi shutai ron). This doctrine, developed by the Japanese Supreme Court primarily in cases involving karaoke establishments and copyright infringement by patrons, allows liability to be imposed on a party who did not directly commit the infringing act but who controls the environment where infringement occurs and profits from it.

Origins in Karaoke Cases

In landmark cases like Maneki Neko (Supreme Court, January 23, 1988) and Club Cat's Eye (Supreme Court, March 15, 2001), karaoke bar operators were held liable for copyright infringement committed by their customers singing copyrighted songs using the karaoke equipment provided by the bar. The Court reasoned that although the customers were the ones physically performing the infringement (singing), the bar owners were the "normative actors" because they:

- Controlled the premises and the overall business operation.

- Provided the essential means for the infringement (karaoke machines, music library).

- Managed the infringing activities occurring within their sphere of control.

- Profited financially from the customers' infringing performances.

The courts deemed it fair to attribute liability to the party managing and profiting from the system that enabled the infringement.

Potential Application to AI Developers and Service Providers

The "Views" document explicitly suggests that this normative actor theory could, under certain circumstances, be applied to AI developers (who create the models) or AI service providers (who make the AI tools available to users). The rationale is analogous to the karaoke cases:

- Control: Developers/providers control the design, training, and functionality of the AI system.

- Means: They provide the essential tool (the AI model/platform) that generates the potentially infringing output.

- Management: They manage the service and potentially the conditions under which outputs are generated.

- Profit: They often derive financial benefit (directly or indirectly) from the use of their AI service.

If an AI developer or provider meets these criteria and infringing outputs are generated by users, they might be considered a normative actor and held liable for copyright infringement, even though they didn't directly generate the infringing output themselves.

Factors Influencing Developer/Provider Liability

The "Views" document outlines several factors that would influence whether an AI developer or service provider could be deemed a liable normative actor:

- Frequency of Infringing Outputs: If a specific AI system is known to generate outputs highly similar to existing copyrighted works frequently or predictably, the provider's responsibility increases.

- Provider's Knowledge and Preventative Measures: If the provider was aware (or reasonably should have been aware) of the high probability that their AI would generate infringing content, but failed to implement reasonable technical measures to prevent or mitigate such outputs (e.g., effective output filters, mechanisms to avoid replicating specific styles identified as problematic), their likelihood of being held liable increases significantly. Conversely, implementing robust preventative measures would decrease this likelihood.

- User's Intent and Input: If an infringing output results primarily from a user's specific intent and detailed instructions aimed at replicating a known work, especially if circumventing provider safeguards, the liability is more likely to remain solely with the user. Liability for the provider is less likely if their system generally avoids infringement but is misused in a specific instance.

- Nature of the AI Service: An AI designed or marketed specifically for purposes likely to lead to infringement (e.g., an AI explicitly marketed as "mimicking famous artists") would face a higher risk of liability.

Essentially, the normative actor theory, as potentially applied to AI, focuses on whether the developer/provider created or maintained a system with a known propensity for infringement without taking adequate steps to control that risk, particularly when profiting from the system's use.

Remedies for AI-Driven Infringement

If copyright infringement through AI generation is established, Japanese law provides standard remedies:

- Injunctions (差止請求 - sashitome seikyū): The copyright holder can demand the cessation of the infringing activity (Article 112). This could include stopping the reproduction, public transmission (e.g., posting online), or distribution of the infringing AI output.

- Against Users: Straightforwardly applies to stop using the infringing output.

- Against Developers/Providers: This is more complex. An injunction might seek "measures necessary for the prevention" of future infringement. The "Views" suggest this could potentially include demanding the removal of the plaintiff's specific copyrighted works from future training datasets if there's a high probability of future infringement. It might also involve demanding the implementation of technical measures to filter or block the generation of outputs similar to the plaintiff's work. However, the "Views" express skepticism about ordering the destruction of an entire pre-trained AI model, viewing it generally as distinct from a mere infringing copy.

- Damages (損害賠償請求 - songai baishō seikyū): Compensation for losses requires proof of intent or negligence (kashitsu) on the part of the infringer (Article 709, Civil Code). As noted, establishing negligence for a user might be complex if they were unaware the work was in the training data. For developers/providers deemed normative actors, establishing negligence might involve showing they knew or should have known about the infringement risks and failed to take reasonable preventative action.

- Unjust Enrichment (不当利得返還請求 - futō ritoku henkan seikyū): Even without intent or negligence, a claim for the return of unjust enrichment might be possible, often calculated based on a reasonable royalty (Article 703, 704 Civil Code).

Comparison with US Secondary Liability Theories

While Japan uses the distinct "normative actor" theory, the underlying goal of holding responsible parties beyond the direct infringer shares similarities with US secondary copyright liability doctrines:

- Vicarious Liability: Holds a defendant liable if they (1) had the right and ability to supervise the infringing activity and (2) derived a direct financial benefit from it. This could potentially apply to AI platform providers who host user activity and profit from it, if they have sufficient control mechanisms.

- Contributory Liability: Holds a defendant liable if they (1) had knowledge of the infringing activity and (2) induced, caused, or materially contributed to it. This might apply to an AI developer/provider if they knew their tool was being used for infringement and provided material assistance or encouragement.

While the specific legal tests differ, both the Japanese normative actor theory and US secondary liability doctrines grapple with attributing responsibility to entities that enable or profit from infringement facilitated by their platforms or tools. The Japanese focus on "management and control" within the normative actor framework may lead to slightly different outcomes than the US focus on supervision/financial benefit (vicarious) or knowledge/material contribution (contributory).

Conclusion

The legal landscape surrounding liability for AI-generated copyright infringement in Japan is complex and evolving. While the direct user of the AI is the primary potential infringer, the unique Japanese "normative actor" theory opens the door for AI developers and service providers to also be held liable under specific conditions. Key factors include the degree of control the provider exerts over the AI system, their knowledge of potential infringing outputs, the frequency of such outputs, and the adequacy of preventative measures taken.

For businesses operating in this space, this means:

- AI Users: Must exercise caution regarding the prompts used and the outputs generated, as they bear primary responsibility. Relying on AI outputs that closely mimic existing works carries direct infringement risk.

- AI Developers/Providers: Face potential liability not just for their direct actions (e.g., infringing training data) but also indirectly for user-generated infringements via the normative actor theory. Implementing robust technical safeguards (e.g., filters, content moderation), designing systems to minimize predictable infringement, and potentially offering indemnities are crucial risk management strategies. Documenting efforts to prevent infringement will be vital in defending against claims of negligence or normative liability.

As generative AI continues to integrate into creative and commercial workflows, understanding this nuanced liability framework under Japanese law is essential for managing risk and fostering responsible innovation.

- Japan’s Article 30-4: Navigating AI Training Data and Copyright Exceptions

- Who Owns AI-Generated Works in Japan? Copyright, Authorship & Article 2 Criteria Explained

- AI and Intellectual Property in Japan: Safeguarding Your Innovations in a New Era

- Perspectives Regarding AI and Copyright (Agency for Cultural Affairs, Mar 2024, PDF)