Levying Special Fees on Non-Resident Condominium Owners in Japan: The "Special Impact" Test Revisited – A 2010 Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: January 26, 2010

Case Number: 2008 (Ju) No. 666 (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench)

Introduction

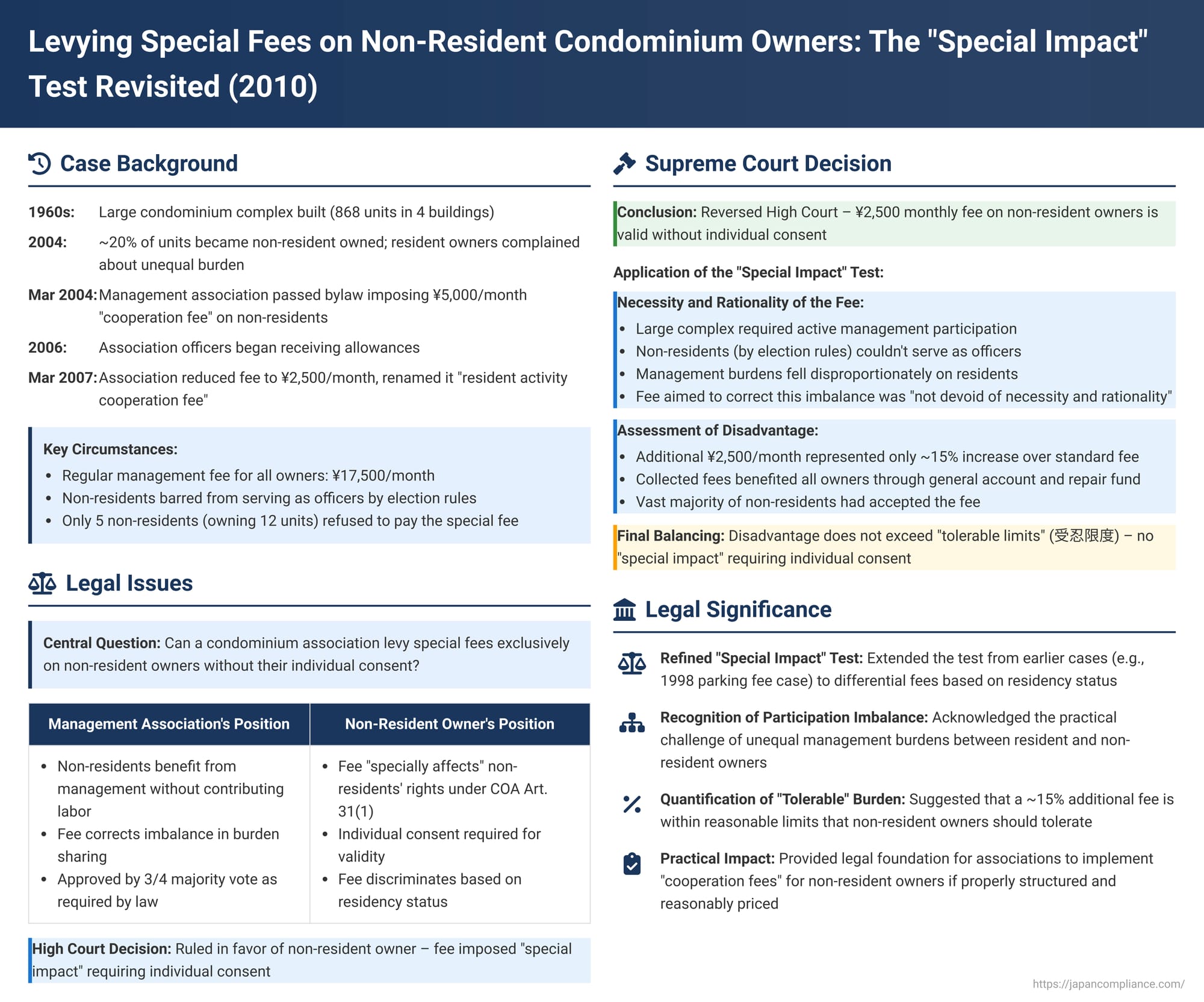

As condominium living has matured in Japan, many older and larger complexes face evolving demographics, including a significant increase in non-resident unit owners (often landlords who lease their units). This trend can lead to a perception among resident owners that they disproportionately shoulder the burdens of day-to-day management, committee work, and community activities, while non-resident owners benefit from a well-maintained property without contributing equivalent effort. In response, some condominium management associations have considered or implemented special fees levied exclusively on non-resident owners to address this imbalance.

A key legal question arising from such measures is whether imposing a differential financial burden based on residency status constitutes a "special impact" on the rights of non-resident owners under Japan's Condominium Ownership Act (COA). If so, their individual consent would be required for the bylaw change imposing the fee to be valid against them. The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this issue in a significant judgment on January 26, 2010, providing important guidance on how to apply the "special impact" test in this context.

Facts of the Case

The case involved "the Condominium" (identified in proceedings as "B Corp"), a large multi-building complex (団地 - danchi) constructed in the 1960s, comprising four buildings and a total of 868 units. The defendant, Y (whose litigation was succeeded by heirs after Y's predecessor, A, passed away), was a non-resident owner of one unit, which was leased to a third party. The plaintiff was X, the Condominium's Management Association.

Background of Management and Fees:

- The Management Association X was responsible for the maintenance and management of the Condominium's site and common areas, as well as for fostering a good living environment and smooth community life. It could delegate specific tasks to various sub-groups composed mainly of unit members.

- All unit members paid a uniform monthly association fee of ¥17,500. This comprised ¥8,500 for general administrative expenses and ¥9,000 for the long-term repair reserve fund.

- Initially, all officers of the Association and members participating in its various sub-groups performed their duties on a voluntary, unpaid basis.

The Growing Issue of Non-Resident Owners and Unequal Burdens:

- According to the Association X's election regulations, individuals eligible to become officers (directors, auditors) had to be residents of the Condominium (or their spouse or a close cohabiting relative). Consequently, non-resident unit owners ("absentee members" - 不在組合員, fuzai kumiaiin) were effectively barred from serving as officers and thus did not share in these leadership responsibilities.

- By around 2004, the number of absentee members in the Condominium had grown significantly. Resident members began to express dissatisfaction, feeling that the operational burdens of the Association fell disproportionately on them. They perceived that absentee members, while benefiting from the upkeep and management of the Condominium, did not contribute to these efforts through labor or participation in governance.

The First Bylaw Change: Introduction of a "Cooperation Fee" (2004):

- To address this perceived inequity, the Association's board proposed a bylaw amendment at a general meeting in March 2004. The proposal was to introduce a "cooperation fee" (協力金 - kyōryokukin) of ¥5,000 per month, to be paid by absentee members in addition to their regular association fees.

- Despite some opposition from absentee members, this bylaw amendment was approved by the requisite special majority vote (as stipulated by the COA Article 31, Paragraph 1, and Article 66 for multi-building complexes, requiring at least three-fourths of both unit owners and voting rights).

Introduction of Officer Allowances and Subsequent Legal Challenges:

- From December 2006, the Association's officers began receiving allowances for their duties, based on resolutions of the board of directors.

- The Association X initiated legal proceedings against several absentee members, including A (Y's predecessor), who refused to pay the ¥5,000 cooperation fee. The outcomes of these first-instance lawsuits varied. In some of the appeal cases, the appellate court suggested a compromise, proposing that the cooperation fee be reduced to ¥2,500 per month.

The Second Bylaw Change: Fee Reduction and Renaming (2007):

- Taking these developments into account, the Association's board proposed further bylaw amendments at a general meeting in March 2007:

- Rename the "cooperation fee" to "resident activity cooperation fee" (住民活動協力金 - jūmin katsudō kyōryokukin).

- Reduce the amount of this fee to ¥2,500 per month, with this change being applied retroactively.

- Formally incorporate provisions into the bylaws authorizing the payment of allowances to officers for their activities.

- These amendments were also approved by the required special majority. (These two sets of bylaw amendments concerning the fee are collectively referred to as "the Bylaw Changes").

- The collected cooperation fees were integrated into the Association's general account, and any year-end surpluses from this account were transferred to the long-term repair reserve fund.

Lower Court Rulings in the Specific Case Against Y (A's Successor):

- Court of First Instance (likely District Court): Ruled in favor of the Management Association X, upholding the claim for the cooperation fee against Y.

- High Court (Appellate Court): Reversed the first instance decision and ruled in favor of Y. The High Court determined that the Bylaw Changes, by imposing a fee exclusively on absentee members, "specially affected" their rights under COA Article 31, Paragraph 1 (as applied to multi-building complexes by Article 66). Since Y's predecessor (A) had not consented to these changes, the High Court deemed them invalid as applied to Y.

The Management Association X appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, on January 26, 2010, overturned the High Court's judgment and ruled in favor of the Management Association X, thereby upholding the validity of the "resident activity cooperation fee" imposed on non-resident members.

1. Reaffirmation of the "Special Impact" Test:

The Court began by reiterating the established legal standard for determining whether a bylaw amendment "specially affects the rights of some unit owners," referencing its own precedent (a 1998 Supreme Court decision, commonly associated with parking fee disputes):

- The determination involves a comparative weighing of:

- The necessity and rationality of the bylaw establishment, change, or abolition.

- The disadvantage thereby incurred by the affected group of unit owners.

- This balancing must be conducted considering the actual circumstances and specific nature of the unit ownership relationship within that particular condominium.

- A "special impact" exists if the disadvantage imposed on the affected unit owners exceeds the limits they should reasonably be expected to tolerate (受忍すべき限度 - junin subeki gendo).

2. Application of the Test to the Facts of This Case:

- Necessity and Rationality of the Bylaw Changes (Imposing the Fee):

- The Condominium was a large complex, and its proper maintenance and the preservation of a good living environment indispensably required the active involvement of the Management Association X, its various sub-groups, and the cooperation of its members.

- A significant and growing number of units (approximately 170 to 180 out of 868) were owned by absentee members.

- Under X's election rules, these absentee members were effectively barred from serving as officers and were thus exempt from the duties and responsibilities associated with these roles. In practice, they also did not contribute labor or participate in the day-to-day activities of the Association.

- Consequently, resident members alone were shouldering the burdens of serving as officers and engaging in various activities essential for the maintenance of the Condominium and its environment, from which all unit members, including absentee members, derived benefits. Absentee members were, in effect, "merely enjoying the benefits" without sharing the operational burdens.

- The Supreme Court stated a general principle: the tasks and expenses necessary for operating a condominium management association should, fundamentally, be borne equally by all its constituent members.

- In this context, the Court found that the Association X's decision to seek a certain monetary contribution from absentee members (who, as a group, generally found it difficult to participate directly in the Association's operations) through the Bylaw Changes, with the aim of correcting the existing disparity and imbalance of burdens between absentee and resident members, was "not devoid of necessity and rationality." (This characteristic Japanese double-negative phrasing implies a positive affirmation, albeit a somewhat reserved one).

- The Court acknowledged the argument that some resident members might also be inactive or unable to participate fully due to age or other reasons, and that exploring some form of contribution from them could be considered. However, given the large proportion of absentee members and their systemic inability (due to election rules and non-residency) to participate in the Association's operational activities, the Court did not find it irrational to target only absentee members for this specific monetary contribution.

- Furthermore, the fact that officer allowances were introduced later (formalized by the 2007 Bylaw Changes) did not negate the necessity and rationality of the cooperation fee. The Court reasoned that the Association's activities were not solely performed by its officers, and therefore, officer allowances did not fully compensate for or redress the broader imbalance of contributions between absentee and resident members.

- Degree of Disadvantage Incurred by Absentee Members:

- The specific disadvantage was the obligation to pay the "resident activity cooperation fee" of ¥2,500 per month.

- This fee, along with the standard association fee of ¥17,500 per month (paid uniformly by all members, resident and non-resident alike), was pooled into the Association X's general account. Any surpluses from this general account were ultimately transferred to the long-term repair reserve fund, benefiting all unit owners.

- The total monthly monetary burden on an absentee member was ¥20,000 (¥17,500 + ¥2,500). This represented an approximate 15% increase over the ¥17,500 paid by resident members. The Court deemed this level of additional financial burden "only" about 15% more.

- Balancing Necessities/Rationality Against Disadvantage, and Final Conclusion on "Special Impact":

- The Supreme Court then weighed the affirmed necessity and rationality of the Bylaw Changes against the assessed degree of disadvantage to the absentee members.

- It also took into additional consideration the fact that, out of the large number of absentee members affected by the fee, only a very small minority (identified as 5 members owning a total of 12 units, out of approximately 180 absentee-owned units) were, at the time of the judgment, still actively refusing to pay the fee on grounds of principle.

- Based on this comprehensive assessment, the Supreme Court concluded that the Bylaw Changes, including the amount of the "resident activity cooperation fee" (¥2,500 per month), did not impose a burden that exceeded the limits absentee members should reasonably be expected to tolerate.

- Therefore, the Bylaw Changes did not fall into the category of measures that "specially affect the rights of some unit owners" as defined in COA Article 31, Paragraph 1 (applied via Article 66).

- Consequently, the Bylaw Changes were valid and enforceable against Y (and other absentee members) even without their individual consent.

The Supreme Court thus reversed the High Court's judgment. Finding no merit in Y's other arguments against the validity of the Bylaw Changes (such as alleged violations of public policy), it effectively reinstated the first instance judgment that had found in favor of the Management Association X and ordered Y to pay the outstanding fees.

Analysis and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's 2010 decision has been influential, offering a significant precedent on the ability of condominium management associations to address participation imbalances through differential fees.

1. Significance of the Ruling:

This judgment is practically important as it provides a clear example where a bylaw imposing a special fee exclusively on non-resident unit owners was upheld by the nation's highest court. Theoretically, it further refines the application of the "special impact" test from COA Article 31, Paragraph 1, to a new set of factual circumstances – differential financial contributions based on residency status and participation levels in management activities.

2. Context within "Special Impact" Jurisprudence:

The Supreme Court explicitly followed the comparative balancing and "tolerable limit" (受忍限度 - junin gendo) framework established in its earlier key rulings, notably the 1998 decision concerning increases in exclusive parking usage fees. This 2010 decision reinforced the utility of that framework while applying it to a distinct type of financial burden – a "cooperation fee" rather than a fee for a specific service or right. While cooperation fees contribute to the overall management budget, they are qualitatively different from standard management fees as they are specifically intended to compensate for a lack of direct labor or participation by a defined subgroup of members.

3. Characteristics of the Supreme Court's Assessment in This Case:

Several aspects of the Court's assessment are noteworthy:

- Affirmation of Necessity/Rationality: The Court's language affirming the necessity and rationality of the fee was somewhat reserved (using double negatives like "not devoid of..."). It did not demand that the association prove this was the only or best possible solution, suggesting a degree of deference to the association's judgment in addressing a real problem.

- Assessment of Disadvantage: The Court characterized the additional ¥2,500 monthly fee (a ~15% increase over what residents paid) as not excessively burdensome. The rationale for including the repair reserve portion of the standard fee in the base for this percentage comparison might be debated by some. Also, the Court did not deeply explore whether the very rule preventing non-residents from becoming officers (which underpinned the rationale for the fee) was itself entirely reasonable or whether it created a qualitative disadvantage for non-residents beyond the fee.

- Weight Given to Majority Compliance: The Court's mention of the small number of dissenting non-resident owners as a factor in finding the burden "tolerable" has drawn comment. While perhaps reflecting the practical acceptance of the measure by most, some critics argue that such reasoning could risk downplaying the protection of legitimate minority rights if applied too broadly.

4. Practical Impact and Trend:

Following this ruling, there has been an observable increase in condominium management associations in Japan considering or implementing similar "cooperation fee" systems for non-resident owners. The Supreme Court's somewhat pragmatic and relatively flexible approach to assessing necessity and rationality may have encouraged this trend.

5. Caution Against Over-Generalization:

Legal commentators caution against an overly broad application of this judgment's outcome. The "special impact" test is, by its nature, highly fact-sensitive and requires an individualized assessment based on the "actual circumstances" of each condominium. The Supreme Court's decision was rooted in the specific facts of "the Condominium" – its large scale, the high proportion of non-resident owners, the clear disparity in management burdens due to existing election rules, and the relatively modest amount of the fee.

Furthermore, the landscape of condominium management continues to evolve. For example, the official Standard Management Rules (upon which many condominiums base their bylaws) have since been revised, and some revisions encourage removing residency requirements for officer eligibility to address officer shortages. Such changes could alter the "necessity and rationality" calculus in future cases. Therefore, while this judgment provides a strong precedent, each association considering such a fee must still carefully evaluate its own unique circumstances against the principles articulated by the Court.

Conclusion

In its 2010 judgment, the Supreme Court of Japan acknowledged the real-world challenges faced by large condominium complexes with a significant number of non-resident owners. It affirmed that a reasonably structured "cooperation fee," levied exclusively on non-resident members to compensate for their general inability to participate in the hands-on management and operational activities of the association, can be a valid measure. Such a fee will not be considered to have a "special impact" requiring individual consent if its necessity and rationality are established, and if the financial burden it imposes is deemed within a tolerable limit, all considered in light of the specific condominium's situation. This ruling offers a pragmatic path for management associations to address participation imbalances but also implicitly calls for careful, context-specific justification for any differential treatment of unit owners.