Lending Your Name for a Loan: Japanese Supreme Court on Consumer Rights in "Sham Credit" Schemes

Judgment Date: February 21, 2017

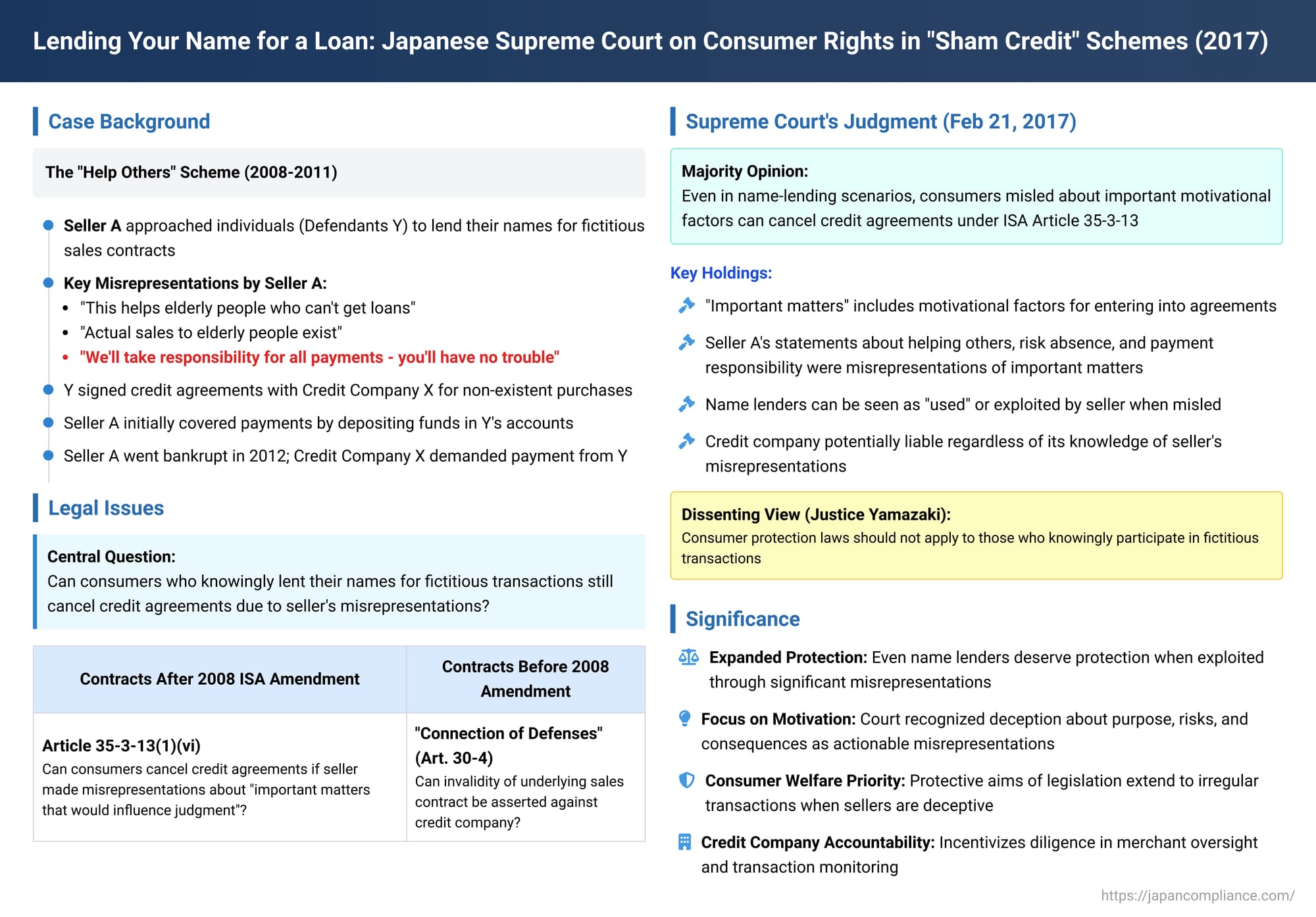

In the complex world of consumer credit, various deceptive practices can unfortunately arise. One such practice involves "name lending" (名義貸し - meigi-gashi), where an individual allows their name to be used to conclude a contract, often for a purchase they do not intend to make or for a transaction that isn't genuine. This is frequently orchestrated by a seller seeking to illicitly obtain funds from a credit company. A pivotal Supreme Court of Japan decision on February 21, 2017 (Heisei 27 (Ju) No. 659) addressed the rights of such "name lenders" when the seller who induced their participation made significant misrepresentations. The case particularly focused on the application of newly amended provisions in Japan's Installment Sales Act (ISA or 割賦販売法 - Kappu Hanbai Hō).

The "Help Others" Ploy: How the Sham Credit Scheme Unfolded

The plaintiff, X, was a credit company that had an affiliate merchant agreement with Seller A, a business engaged in the wholesale and retail of kimonos, jewelry, and similar items, from around April 2004. The defendants, Y et al. (referred to collectively as Y), were individuals who, between November 2008 and November 2011, were earnestly requested by Seller A to participate in a name-lending scheme.

Y agreed to have fictitious sales contracts (for goods they neither intended to purchase nor receive) formally concluded in their names with Seller A. Simultaneously, they signed payment advance agreements (立替払契約 - tatekaebarai keiyaku), which are essentially three-party credit contracts, with X Credit Company for the purported purchase prices of these non-existent goods. These transactions were structured to appear as "door-to-door sales" (訪問販売 - hōmon hanbai), a category specifically regulated under Japan's Act on Specified Commercial Transactions (SCTA) and often subject to stricter consumer protection rules under the ISA.

When soliciting Y to enter into these credit agreements, Seller A made several key misrepresentations:

- A told Y that the purpose of these contracts was "to help elderly people and others who cannot obtain loans themselves."

- A assured Y that genuine sales contracts with these third-party elderly individuals and the actual delivery of goods to them did exist.

- Most importantly, A told Y, "We (Seller A) will take full responsibility for the payments, so you will absolutely not be troubled (financially)."

For a period, this arrangement appeared to function as A described, at least from Y's perspective regarding payments. The installment payments due to X Credit Company under Y's name were made via direct debit from Y's bank accounts. However, up until October 2011, Seller A effectively covered these payments by depositing equivalent amounts into Y's accounts.

The scheme unraveled when Seller A ceased operations in November 2011 and subsequently filed for bankruptcy in April 2012. With A no longer covering the payments, X Credit Company turned to Y (the nominal debtors on the credit agreements) and demanded payment of the outstanding balances.

The Legal Defenses: Cancellation Under the Amended ISA and "Connected Defenses"

X Credit Company initiated lawsuits against Y to recover the unpaid amounts. Y raised several defenses:

- For contracts concluded after the 2008 amendments to the Installment Sales Act ("Post-Amendment Contracts"): Y argued for the cancellation (取 消 - torikeshi) of their credit agreement applications under the newly introduced Article 35-3-13, Paragraph 1 of the ISA. This provision allows consumers to cancel a credit agreement if the seller, acting as an intermediary in soliciting the credit agreement, made misrepresentations about certain important matters. Y contended that Seller A's assurances constituted such misrepresentations.

- For contracts concluded before the 2008 ISA amendments ("Pre-Amendment Contracts"): Y argued that the underlying sham sales contracts with A were void (e.g., under former Civil Code Article 93 proviso – mental reservation, or Article 94, Paragraph 1 – fictitious declaration of intent). They claimed they could assert this voidness as a defense against X Credit Company's payment demands, based on the principle of "connection of defenses" (抗弁の接続 - kōben no setsuzoku) provided for in former ISA Article 30-4, Paragraph 1.

The first instance court (Asahikawa District Court) largely sided with Y, finding that A's statement about Y having no payment burden was a misrepresentation, and that Y's assertion of defenses was not contrary to good faith. It dismissed X Credit Company's claims.

However, the Sapporo High Court reversed this decision. It held that since Seller A had actually covered the payments until its business failure, A's statements about Y not having to pay were not, in fact, misrepresentations at the time they were made. Furthermore, the High Court ruled that Y, having knowingly lent their names for these fictitious transactions, could not assert the invalidity of the underlying sales against X Credit Company because doing so would be contrary to the principle of good faith. It granted X Credit Company's claims. Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Interpretation of ISA Article 35-3-13 (Post-Amendment Contracts)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of February 21, 2017, focused significantly on the application of the amended Installment Sales Act Article 35-3-13, Paragraph 1, particularly its Item 6.

- Purpose and Scope of ISA Article 35-3-13: The Court explained that this provision was introduced in the 2008 ISA reforms to significantly bolster consumer protection, especially in contexts like door-to-door sales that are often linked with credit agreements. It recognizes the close operational relationship between sellers (who frequently act as intermediaries for credit applications) and credit companies. The provision was designed to address situations where a seller's improper solicitation tactics could lead to a consumer's flawed consent in entering into a credit agreement.

Critically, Article 35-3-13 allows a consumer to cancel their offer or acceptance of a credit agreement if the seller, when soliciting that credit agreement, made a misrepresentation about "important matters that would influence the purchaser's judgment" concerning either the sales contract or the credit contract. This right of cancellation against the credit company applies regardless of whether the credit company itself knew, or could have known, about the seller's misrepresentation. This provision acts as a special rule, strengthening consumer rights beyond those generally available under Articles 4 and 5 of the Consumer Contract Act. - "Important Matters" Broadly Defined to Include Motivational Factors: The Supreme Court clarified that the "important matters" referred to in item (vi) of ISA Article 35-3-13, Paragraph 1 – which covers misrepresentations by the seller about "important matters that would influence the purchaser's or service recipient's judgment" – is not limited to the direct terms or quality of the goods/services or credit. It can also include matters concerning the motive for concluding the contract.

- Application to Name-Lending Scenarios: The Court then addressed the core issue: can this provision apply when the consumer knowingly participated in a "name-lending" scheme for what they knew were fictitious sales?

The Supreme Court held that even if a credit agreement was concluded through the irregular method of name lending with the nominal purchaser's consent, if this participation was based on the seller's request and that request was accompanied by misrepresentations about important motivational factors, then the name lender might still be able to cancel the credit agreement under ISA Art. 35-3-13.

The key factors for this consideration include misrepresentations by the seller regarding:- The alleged necessity for the contract (e.g., "helping others").

- The presence or absence of actual risks for the nominal purchaser.

- The likelihood of the credit company suffering any real financial loss (e.g., due to the seller's assurances of covering payments).

If such misrepresentations led the nominal purchaser to a mistaken understanding and, as a result, they entered into the credit agreement, the Court found that these individuals could be seen as having been "used" or exploited by the seller. In such circumstances, they are not automatically undeserving of legal protection, and allowing them to cancel the credit agreement due to the seller's significant misrepresentations about these motivational aspects would not contravene the purpose of ISA Article 35-3-13.

- Seller A's Statements as Misrepresentations of Important Motivational Matters: The Supreme Court found that Seller A's statements to Y—that the scheme was "to help elderly people who couldn't get loans," that actual underlying sales contracts and goods deliveries to these elderly individuals existed, and the crucial assurance that "we (Seller A) will take full responsibility for the payments, so you will absolutely not be troubled"—were indeed statements concerning:

- The purported reasons why Y's participation was necessary.

- The (supposed lack of) financial risk Y would personally bear.

- The (supposed lack of) possibility that X Credit Company would suffer any actual loss because A would ensure all payments were made.

The Court concluded that these representations directly pertained to important matters related to Y's motive for agreeing to enter into the credit contracts.

- Remand for Factual Assessment of Misrepresentation and Reliance: Based on this interpretation, the Supreme Court ruled that Seller A's statements did qualify as statements about "important matters that would influence the purchaser's judgment" under ISA Article 35-3-13(1)(vi). The High Court had erred in finding no actionable misrepresentation. Therefore, the portion of the case concerning the Post-Amendment Contracts was remanded to the High Court for a factual determination of whether Y et al. were indeed misled by these misrepresentations into signing the credit agreements.

Consideration for Pre-Amendment Contracts

For the contracts concluded before the 2008 ISA amendments, the primary defense available to Y was the "connection of defenses" under former ISA Article 30-4. This would allow Y to argue that the underlying sham sales contracts with A were void (e.g., due to being fictitious declarations of intent or due to A's fraudulent inducement) and that this voidness should serve as a defense against X Credit Company's claims under the credit agreements.

The High Court had rejected this, finding that for Y (as name lenders) to assert such defenses against the credit company would be contrary to the principle of good faith. The Supreme Court found that the High Court's reasoning on this point was likely influenced by its (erroneous) finding that there were no actionable misrepresentations by Seller A. Therefore, the Supreme Court also remanded this part of the case for the High Court to reconsider whether, given the full context of Seller A's misrepresentations and the circumstances under which Y agreed to lend their names, asserting the invalidity of the sales contracts against X Credit Company would indeed violate the principle of good faith.

The Dissenting View: Should Knowing Participants in Sham Transactions Receive Statutory Protection?

Justice Toshimitsu Yamazaki dissented from the majority opinion regarding the application of ISA Article 35-3-13 to name-lending situations. He argued that name lending, where the nominal purchaser is aware that the underlying sales contract is fictitious and that they will not actually receive the goods, is a situation markedly different from those the Installment Sales Act primarily intends to protect (i.e., consumers involved in genuine, albeit perhaps improperly induced, purchase transactions). Justice Yamazaki was of the view that extending the protections of ISA Art. 35-3-13 to individuals who knowingly participated in such fundamentally irregular and arguably "improper" transactions by lending their names was not appropriate and did not align with the legislative intent of the provision. This dissenting view reflects a more traditional skepticism towards granting relief to parties who are, at some level, aware of the fictitious nature of the underlying transaction.

Implications of the Majority Decision

The Supreme Court's majority decision in this 2017 case is significant for several reasons:

- Expanded Protection for "Used" Consumers in Name-Lending Schemes: The ruling broadens the protective ambit of the amended Installment Sales Act (specifically Art. 35-3-13) to potentially include individuals who, while formally agreeing to "lend their name" for what they know are not genuine purchases for themselves, were nonetheless victims of significant misrepresentations by the seller regarding the purpose, risks, and financial consequences of their participation. The Court recognized that such individuals are often "used" by fraudulent sellers and may still warrant protection.

- Focus on Seller's Misrepresentations about Motivational Factors: The decision places crucial emphasis on the nature of the seller's representations when inducing someone to participate in a name-lending scheme. If the seller lies about why the name lending is needed, who will ultimately bear the financial responsibility, or the risks involved, these can be considered misrepresentations of "important matters" allowing the nominal purchaser to cancel the linked credit agreement against the credit company.

- Balancing Culpability and Protecting Vulnerable Parties: The judgment reflects a nuanced approach to balancing the formal irregularity of name-lending with the potential vulnerability of individuals who are persuaded into such schemes through deceit and exploitation of trust or goodwill. It suggests that merely knowing a sale is fictitious does not automatically strip a name lender of all consumer protections if they were fundamentally misled about the implications for the credit agreement they signed.

- Reinforcing Credit Company Responsibilities (Indirectly): While ISA Article 35-3-13 allows cancellation against the credit company irrespective of its own knowledge of the seller's misdeeds, rulings like this indirectly incentivize credit companies to be more diligent in their oversight of affiliated merchants and the types of transactions they are financing, as the risk of cancellation due to seller misconduct now more clearly extends even to these irregular name-lending scenarios.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's February 2017 decision regarding name lending in sham credit transactions marks an important development in Japanese consumer protection law. It demonstrates a willingness to look beyond the formal act of name lending and scrutinize the seller's conduct in inducing such participation. By interpreting "important matters" under the amended Installment Sales Act to include motivational factors, the Court has opened a pathway for nominal purchasers who were misled about the purpose and risks of their involvement to potentially cancel their obligations to credit companies. This ruling underscores the protective aims of consumer legislation, even for individuals involved in transactions that deviate from standard commercial norms, when they are victims of misrepresentation by unscrupulous sellers.