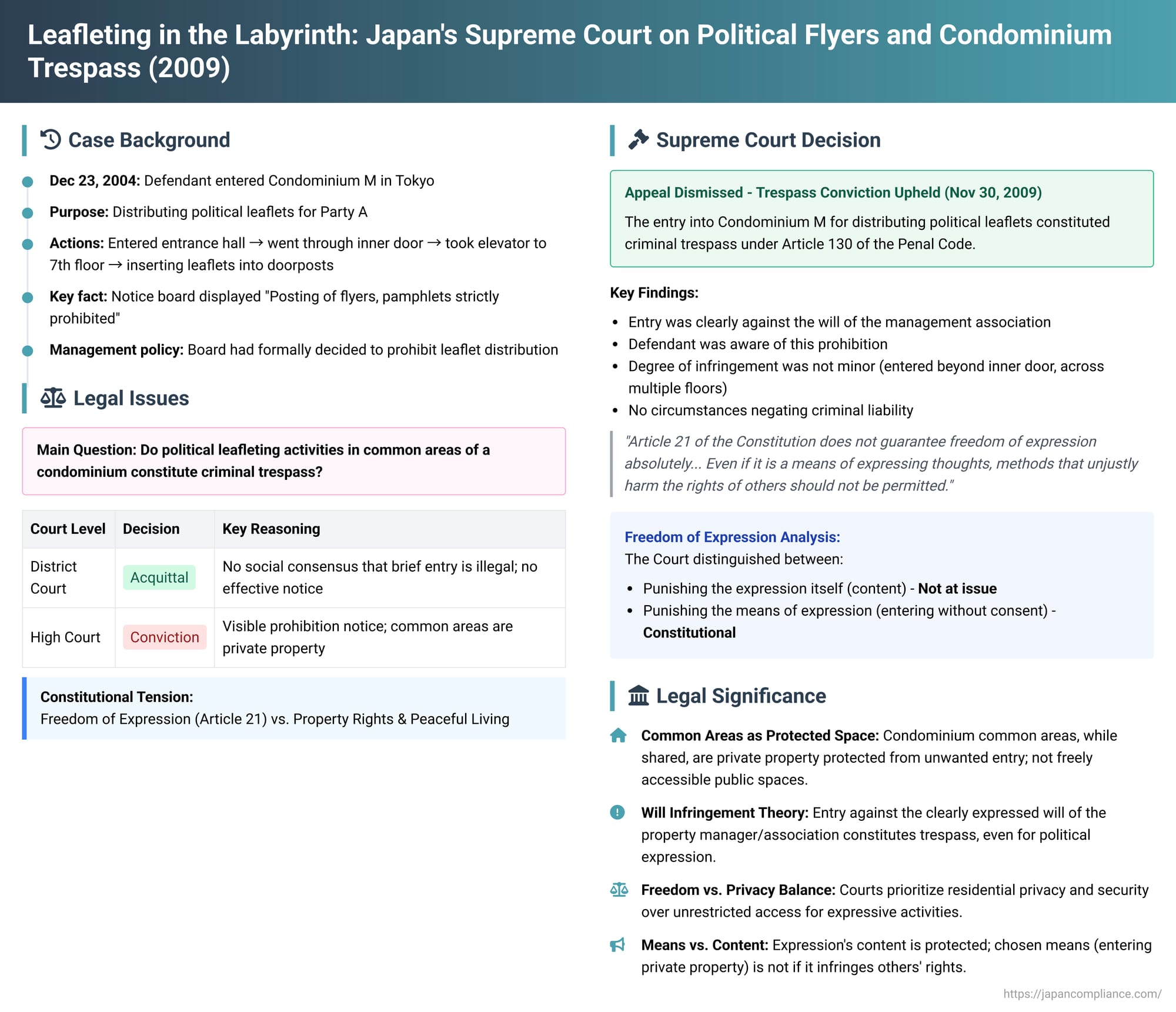

Leafleting in the Labyrinth: Japan's Supreme Court on Political Flyers and Condominium Trespass

The distribution of leaflets and flyers is a common method for disseminating information, from commercial advertisements to political manifestos. However, when does this activity cross the line from legitimate outreach to criminal trespass, particularly when it involves entering private residential complexes? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this sensitive issue in a judgment on November 30, 2009 (Heisei 20 (A) No. 13), in a case concerning a defendant charged with住居侵入 (trespass) for distributing political leaflets within a condominium.

The Facts: A Political Campaign Reaches Private Doors

The defendant, on the afternoon of December 23, 2004, entered Condominium M in Katsushika Ward, Tokyo, with the purpose of distributing leaflets for Political Party A's Katsushika Ward assembly representatives. The defendant opened the main entrance door of Condominium M, entered the entrance hall, proceeded through an inner door on the east side, walked down a first-floor corridor, and then took an elevator to the seventh floor. The defendant was in the process of inserting the leaflets into the doorposts of individual residential units when a resident confronted them, at which point the leaflet distribution was halted.

Condominium M was a seven-story (with a basement) reinforced concrete building where units were individually sold (bunjō manshon). The entrance for the residential units (second floor and above) was completely separate from the entrances to the shops and offices located on the first floor. Upon entering the residential section, one would find an entrance hall containing a notice board and collective mailboxes. A conspicuous notice, bearing the name of the condominium's management association, was posted in a prominent position on the notice board, stating: "Posting of flyers, pamphlets, and other advertisements is strictly prohibited." A building manager was typically on duty only during daytime on weekdays. Furthermore, the board of directors of Condominium M's management association had formally decided to prohibit entry for the purpose of distributing any leaflets to the collective mailboxes, with the sole exception of official newsletters from the local ward office.

The Legal Path: From Acquittal to Conviction

The case saw differing outcomes in the lower courts:

- First Instance (Tokyo District Court): The defendant was acquitted. The court acknowledged that the common areas entered by the defendant (corridors, etc.) could be considered part of a "residence" under Article 130 of the Penal Code (which criminalizes unlawful entry into a person's residence, or guarded building or vessel). However, it reasoned that, even considering heightened contemporary awareness of privacy and crime prevention, there was no established societal consensus that briefly entering the common areas of a typical residential condominium during the daytime to distribute leaflets to individual doorposts was an inherently illegal act of intrusion. While the management association had an internal policy against such leaflet distribution, including for political purposes, the court found that effective measures to physically prevent or clearly forbid entry to all visitors for such purposes were not in place at the time. Therefore, the entry could not be definitively classified as lacking "justifiable reason."

- Appellate Court (Tokyo High Court): The prosecution appealed, and the High Court overturned the acquittal, finding the defendant guilty of trespass. The High Court noted that the notice prohibiting leaflet distribution was posted in a prominent location visible to anyone entering the entrance hall, and it concluded the defendant was aware of this notice. It disagreed with the notion that society broadly permits outsiders without specific business to enter multi-unit dwellings. The court found that effective measures to communicate the prohibition of entry beyond the inner east door were not lacking. It emphasized that the common areas of a condominium, even if shared, are private property subject to the property and management rights of the residents (as co-owners). Residents are not obliged to tolerate entry that goes against their expressed will. Consequently, convicting the defendant for entering without permission from the management (acting on behalf of residents) or individual residents did not violate Article 21, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution (guaranteeing freedom of expression).

The defense subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Stance (November 30, 2009): Trespass Affirmed

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, upholding the High Court's guilty verdict.

The Court's key reasoning was as follows:

- Entry Against Management's Will & Defendant's Awareness: "Given the structure and management condition of Condominium M, the situation within the entrance hall, the content of the aforementioned posted notice, and the purpose of the entry," the Court found it "clear that the act of entry was contrary to the will of the management association of Condominium M, and it is recognized that the defendant was also aware of this."

- Non-Trivial Infringement: The Court highlighted that Condominium M was a condominium where units were sold to individual owners. The defendant's actions involved opening an inner door and entering the corridors and stairwells from the seventh down to the third floor. In light of these factors, "the degree of infringement of legal interests cannot be said to have been extremely minor." Finding no other circumstances that would negate criminal liability, the Court concluded that the act of entry constituted a crime under the first part of Penal Code Article 130.

Freedom of Expression vs. Property Rights and Peaceful Living

A significant part of the appeal concerned the intersection of criminal trespass with the constitutional right to freedom of expression.

- The Supreme Court acknowledged that distributing political leaflets, like those in this case containing Political Party A's political opinions, "can be described as an exercise of freedom of expression."

- However, it reiterated a well-established principle: "Article 21, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution does not guarantee freedom of expression absolutely and without limit, and it accepts necessary and reasonable restrictions for the public welfare. Even if it is a means of expressing thoughts externally, methods that unjustly harm the rights of others should not be permitted."

- Means vs. Content: The Court drew a crucial distinction: "In this case, the constitutionality of punishing the expression itself is not being questioned; rather, it is the constitutionality of punishing the act of entering Condominium M without the consent of its management association for the purpose of distributing leaflets, i.e., the means of expression."

- Nature of the Location: The Court emphasized that the areas entered by the defendant—the common corridors and other shared spaces within Condominium M—were "parts of a residential building where the residents of Condominium M conduct their private lives, managed as such by the management association composed of its owners, and are not places where people can generally enter and exit freely."

- Infringement of Rights: Therefore, "even for the exercise of freedom of expression, entering such a place against the will of the management association of Condominium M not only infringes the management rights of the said management association but also must be said to infringe the peace of the private lives of those who conduct their private lives there."

- Conclusion on Constitutionality: Consequently, convicting the defendant for this act of entry under Penal Code Article 130 "does not violate Article 21, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution."

Deeper Dive: Defining "Intrusion" and Its Boundaries

The case touches upon several core concepts in Japanese criminal law regarding trespass.

- What is a "Residence" for Trespass Purposes? Article 130 of the Penal Code refers to unlawfully entering a "residence" (jūkyo), or a guarded "building or vessel" (kenzōbutsu). The commentary notes that the High Court (and the First Instance court) considered the common areas of Condominium M as part of the "residence" because of their intrinsic connection to the private dwelling units and the need to protect the peaceful daily life of the residents. The Supreme Court, while affirming the conviction under Article 130, did not explicitly label the common areas as "residence" in its judgment. This is interesting in light of a previous Supreme Court case (the Tachikawa Public Servants' Dormitory case, Heisei 20.4.11), which classified common areas of a government-managed dormitory as a "mansion/residence" (teitaku, a term often encompassing a dwelling and its enclosed grounds, usually implying a manager's oversight) rather than strictly "residence" (jūkyo).

- The "Will Infringement" Theory of Intrusion: The prevailing legal theory in Japan for "intrusion" (shinnyū) is the "will infringement theory" (ishi shingai setsu). This means that an intrusion occurs when someone enters a place against the will of the person who has the right to control access—typically the resident in the case of a home, or the manager in the case of a controlled building. For the common areas of a condominium owned by its residents, the will of the management association (representing the collective owners) is considered primary. The Supreme Court's approach, consistent with a prior precedent (Showa 58.4.8), involves assessing whether the access controller would not have tolerated the entry, based on factors like the building's nature, purpose, management status, the controller's attitude, and the purpose of the entry—even if an entry refusal wasn't actively displayed at the exact moment. However, in this specific case, the Supreme Court did explicitly refer to the "posted notice" and the defendant's awareness of it as key factors.

- The Element of Intent (Koi): For criminal liability, the defendant must have the intent to trespass. If the access controller's will to prohibit entry is not manifested externally in a way that an ordinary person could perceive, the defendant might argue they were unaware their entry was unwelcome, potentially negating intent. The First Instance court leaned in this direction, citing a lack of "effective measures" to communicate the ban that would be understood by any visitor at the time of entry. However, the High Court and the Supreme Court found that the posted notice and the physical layout of Condominium M (requiring passage through an inner door to reach residential areas) were sufficient to establish that the defendant was, or should have been, aware of the prohibition against their entry for leafleting.

- The "De Minimis" Argument: The defense might argue that such an entry is a trivial infraction. However, the Supreme Court explicitly stated that due to the extent of the entry (beyond the inner door and across multiple floors of a bunjō manshon), the infringement of legal interests was "not extremely minor."

Lingering Questions and Implications

While the Supreme Court's decision provides clarity on this specific set of facts, some questions and broader implications arise from the judgment and the surrounding legal commentary:

- The Significance of the Point of Entry: The Supreme Court noted the defendant went beyond the "entrance hall inner east door" and onto multiple upper floors. Some legal commentators have suggested that if the defendant had confined their activities to the initial entrance hall and only deposited leaflets into the collective mailboxes (which were also subject to a ban by the management association, except for official ward mailings), the constitutional analysis regarding freedom of expression might have been different, or the trespass claim itself potentially viewed as more minor. The act of proceeding deep into purely residential common areas appears to have weighed heavily.

- Selective Enforcement Concerns: A critique raised by some commentators is the potential for arbitrary or selective enforcement of trespass laws against leafleting. If commercial flyers (e.g., for food delivery services) are routinely distributed in a similar manner without criminal prosecution, but political leafleting is targeted, it could raise questions about whether the regulation is truly content-neutral in practice, despite appearing so on its face.

- Balancing Democratic Activities and Residential Peace: The case highlights the delicate balance between activities considered vital for a democratic society, such as political campaigning and the dissemination of political opinions, and the rights of individuals to privacy, security, and the peaceful enjoyment of their homes. The Supreme Court's decision indicates a strong leaning towards protecting the latter in the context of private residential spaces when a clear will to restrict access is communicated.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2009 judgment in the Kunitachi condominium leafleting case affirms that entering the common areas of a private residential complex for purposes like distributing political leaflets, when such entry is clearly against the expressed will of the property's management and this prohibition is known to the entrant, can constitute criminal trespass. The Court prioritized the management rights of the condominium association and the residents' interest in maintaining the peace and security of their private living environment over an unrestricted right to use private property as a forum for expression. This ruling underscores the importance for condominium associations to clearly communicate access restrictions and for individuals and groups engaged in leafleting to be mindful of these boundaries to avoid potential criminal liability.