Leadership, Trust, and Tragic Error: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Medical Team Responsibility in Anticancer Drug Overdose

Date of Decision: November 15, 2005, Supreme Court of Japan (First Petty Bench)

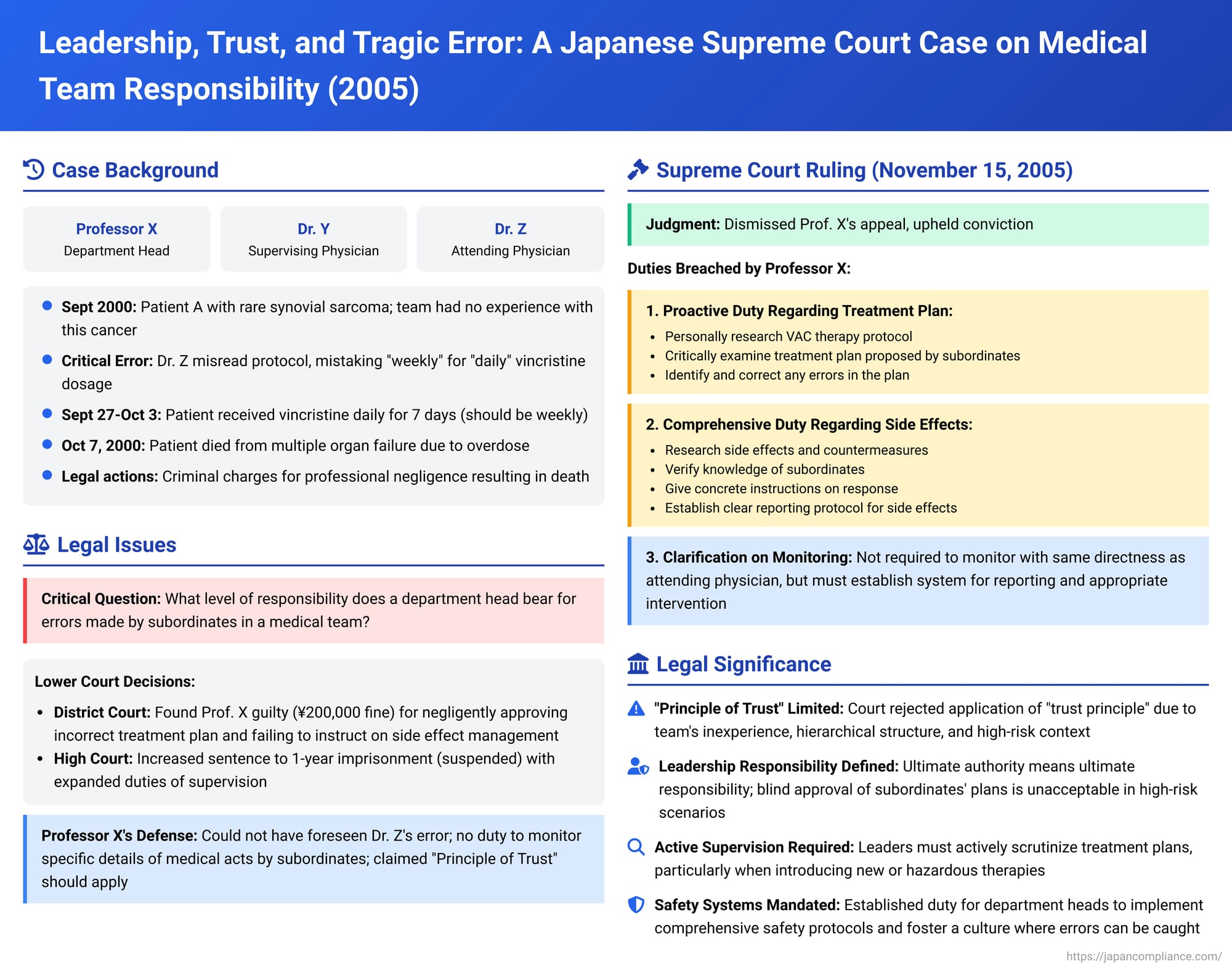

The complexities of modern medical treatment often necessitate a team-based approach, pooling the expertise of various professionals. However, this collaborative model can also lead to tragic errors if roles, responsibilities, and oversight are not meticulously managed. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on November 15, 2005, addressed the criminal liability of senior supervising physicians in a case involving a fatal overdose of an anticancer drug due to a misread protocol within a university hospital's medical team. This case provides crucial insights into the duties of care expected from those in leadership positions within such medical teams.

The Tragic Error: Facts of the Case

The case involved Patient A, who was suffering from synovial sarcoma in the right submandibular region, a rare and aggressive cancer with a poor prognosis. Given the rarity of the disease, the medical team at a University Hospital (referred to in the judgment as "the Center") had no prior clinical experience with treating this specific condition.

The medical team responsible for Patient A's care included:

- Professor X: The head of the Otolaryngology Department and a professor at the university, who was responsible for the overall supervision of medical care within the department and for guiding and overseeing its physicians.

- Dr. Y: A university assistant, designated as the supervising physician (指導医 - shidōi) for Patient A's treatment team.

- Dr. Z: A hospital assistant, serving as the attending physician (主治医 - shujii) for Patient A.

The team decided to implement VAC therapy, a combination chemotherapy regimen involving three anticancer drugs: vincristine sulfate, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide. This therapy was also new to the entire team, including Professor X.

The critical error occurred when Dr. Z, the attending physician, was preparing the treatment plan. While consulting a VAC therapy protocol found in medical literature, Dr. Z misread the dosage schedule for vincristine sulfate, mistaking the instruction "week" (週 - shū) for "day" (日 - nichi). Consequently, Dr. Z formulated a treatment plan that called for vincristine (2mg) to be administered daily for 12 consecutive days, instead of the correct dosage of once per week (with a maximum single dose of 2mg).

This erroneous plan was subsequently put into action. Patient A received 2mg of vincristine sulfate intravenously every day for seven consecutive days, from September 27 to October 3, 2000. As a result of this massive overdose, Patient A suffered severe side effects and died on October 7, 2000, from multiple organ failure.

The Legal Proceedings: From Trial Court to High Court

Criminal charges for professional negligence resulting in death were brought against Professor X, Dr. Y, and Dr. Z.

- Dr. Z (Attending Physician): His conviction was finalized at the trial court level (Saitama District Court). He was found negligent for creating the erroneous dosage plan and for failing to respond appropriately to Patient A's severe side effects. He received a sentence of two years imprisonment, suspended for three years.

- Professor X (Department Head) and Dr. Y (Supervising Physician):

- Trial Court (Saitama District Court): Found both X and Y guilty. Their negligence was identified as:

- Negligently approving Dr. Z's incorrect treatment plan, thereby allowing the overdose.

- Failing to adequately instruct Dr. Z beforehand on how to manage the potential side effects of VAC therapy.

Professor X was fined 200,000 yen, and Dr. Y was fined 300,000 yen.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): Both the prosecution and defendants X and Y appealed. The High Court upheld the finding of negligence regarding the approval of the erroneous treatment plan (point 1 above) for both X and Y. However, it found that the trial court had erred in its assessment of their duties concerning side effect management. The High Court believed their responsibility extended beyond just prior instruction.

It found Professor X negligent for:- Approving the incorrect plan.

- Failing in his duty to accurately grasp Patient A's treatment status and the emergence of side effects, and to promptly implement appropriate countermeasures when severe side effects appeared. This failure included neglecting to check Patient A's medical chart during his professorial rounds.

The High Court found Dr. Y negligent for: - Approving the incorrect plan.

- As the supervising physician, failing to accurately monitor Patient A's treatment and side effects. He had neglected to examine Patient A until her condition had significantly deteriorated, thereby overlooking severe side effects and failing to take timely and appropriate action.

The High Court increased the sentences: Professor X received a one-year prison sentence, suspended for three years, and Dr. Y received a one-year and six-month prison sentence, also suspended for three years. Dr. Y's conviction became final at this stage.

- Trial Court (Saitama District Court): Found both X and Y guilty. Their negligence was identified as:

Professor X appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court of Japan. He argued, among other points, that he could not have foreseen Dr. Z’s error and that he had no duty to monitor the specific details of medical acts carried out by his subordinates.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Stance (November 15, 2005)

The Supreme Court dismissed Professor X's appeal, upholding his conviction. In its decision, the Court exercised its authority to provide a detailed clarification of the duties incumbent upon Professor X in his capacity as department head and overall supervisor.

The Supreme Court found that Professor X had breached several key duties of care:

- Proactive Duty Regarding Treatment Plan Formulation:

The Court emphasized that given the circumstances—the extreme rarity of Patient A's illness (no prior experience within the department, including for X himself), the fact that VAC therapy was being implemented for the first time by the team, the known severe and potentially fatal toxicity of vincristine if misused (with overdose deaths already reported in medical literature), and Professor X's awareness that physicians in his department generally required careful guidance to prevent errors—Professor X had a profound duty that went beyond passive approval.

He was obligated to:- Personally research and investigate VAC therapy, including reviewing clinical examples, medical literature, and the drug's official package insert to understand its appropriateness, correct dosage, administration methods, and potential side effects.

- Critically and specifically examine the content of any proposed treatment plan formulated by his subordinates (Dr. Z and Dr. Y).

- Identify and correct any errors in such a plan.

The Court noted it would have been easy for Professor X to fulfill this duty by requiring Dr. Z to report the detailed treatment plan to him between September 20th (when B sought approval for VAC therapy) and September 28th (when a conference was held after administration began). His failure to grasp the concrete details of the plan and assess its appropriateness, instead merely approving the choice of VAC therapy without scrutinizing the dosage, constituted negligence.

- Comprehensive Duty Regarding Side Effect Management:

Even if a treatment plan is initially correct, errors in administration or the emergence of severe side effects can lead to harm or death. Given the team’s inexperience with VAC therapy and their insufficient knowledge of its side effects and management, Professor X was deemed to have a duty to foresee that his subordinates might fail to appropriately identify and respond to side effects.

Therefore, Professor X was obligated to:- Personally research the side effects of VAC therapy and the methods to counteract them.

- Verify the knowledge of Dr. Z and Dr. Y regarding vincristine's side effects.

- Provide them with prior, concrete instructions on how to respond effectively to these side effects.

- Specifically direct them to report immediately to him if any anticipated severe side effects manifested.

The Supreme Court concluded that if Professor X had fulfilled these duties, Patient A’s life could have been saved, as the severe side effects would have been identified and acted upon, at the latest, by October 1st (the fifth day of overdose), when strong side effects were already apparent. His failure to perform these actions constituted negligence.

- Clarification on the Scope of X's Side Effect Monitoring Duty:

The Supreme Court addressed the High Court's formulation of Professor X's duty regarding side effect management. It stated that if the High Court meant Professor X had a duty to monitor Patient A's side effects with the exact same directness and immediacy as the attending physician (Dr. Z), such a duty would be "excessive" (kadai na chūi gimu). However, the Supreme Court interpreted the High Court's judgment as encompassing the duties of prior instruction and ensuring a system for reporting and response was in place—that is, a duty to instruct subordinates on side effect management beforehand and to stay informed through reports from them to prevent adverse outcomes. Understood in this light, the High Court's finding was deemed justifiable.

Discussion: The "Principle of Trust" in Team Medicine

A key legal concept often discussed in cases of team-based error is the "Principle of Trust" (shinrai no gensoku). Generally, this principle allows members of a professional team, under certain conditions, to trust that their colleagues will properly perform their assigned tasks, absolving them of liability for errors committed by those colleagues.

However, in this particular case involving Professor X, this principle was effectively deemed inapplicable due to several "special circumstances" that undermined the basis for such trust:

- Rarity of Disease and Universal Inexperience: Neither Professor X nor any member of his team had prior experience with Patient A's specific type of sarcoma or with the VAC chemotherapy regimen. This shared inexperience necessitated a higher degree of caution and mutual checking than in routine procedures.

- Hierarchical Structure and Final Authority: Professor X was not merely a colleague but the department head with ultimate decision-making authority regarding treatment plans. Dr. Z and Dr. Y were his subordinates operating under his guidance and supervision, not fully independent practitioners in this context.

- Critical Nature of Anticancer Drug Dosage: The administration of potent anticancer drugs like vincristine carries inherent, well-documented risks of severe harm or death if dosages are incorrect. This demands exceptional scrutiny at all levels, especially from the supervising authority. The error—misreading "weekly" for "daily"—was a fundamental mistake in a high-stakes context.

- Opportunities for Intervention: Professor X had multiple opportunities to review the treatment plan and monitor its initial progress, including through direct reports, departmental conferences (where Patient A's case was discussed, albeit without full dosage details being presented by Dr. Z), and his own professorial rounds.

- Acknowledged Need for Guidance: Professor X himself felt that the physicians in his department generally required his careful guidance and supervision to prevent errors. This pre-existing awareness heightened his responsibility.

This case, therefore, serves as a significant example of how "special circumstances" can negate the typical application of the "Principle of Trust," even among qualified medical professionals working in a team. The gravity of the potential harm, the inexperience of the team, and the hierarchical command structure all pointed towards a heightened, non-delegable oversight responsibility for Professor X.

Nature of a Supervisor's Negligence: Direct and Systemic Failures

The negligence attributed to Professor X by the Supreme Court was not merely a passive failure to supervise but involved breaches of active, personal duties:

- Failure in Direct Oversight of Critical Plan Elements: His negligence included failing to personally verify the fundamental details (like drug dosage and administration frequency) of a high-risk treatment plan he approved, despite the team's collective inexperience.

- Failure to Establish Robust Safety Systems: He also failed to ensure adequate systems were in place for the safe execution of the therapy. This included a lack of proactive measures to educate his team about the specific drugs and their side effects, failure to issue clear prior instructions on managing these side effects, and critically, a failure to mandate a clear reporting line for when such side effects occurred.

This judgment implies that the responsibility of a department head in such situations transcends simple vicarious liability for subordinates' errors. It points to direct, personal duties of care related to ensuring the safety and appropriateness of treatments administered under their overall command, particularly when those treatments are novel, complex, or inherently dangerous.

Implications for Medical Team Leaders

The Supreme Court's decision in this tragic case carries profound implications for physicians in leadership and supervisory roles within medical teams:

- Ultimate Authority Means Ultimate Responsibility: Those with final decision-making power, such as department heads, cannot operate under the assumption that subordinates will always perform flawlessly, especially when introducing new or hazardous therapies.

- Scrutiny of Subordinates' Plans: Supervising physicians have a duty to actively scrutinize and verify critical aspects of treatment plans proposed by their subordinates, particularly in areas of shared inexperience or high patient risk. Blind approval is not an option.

- Proactive Safety Protocols: Leaders are responsible for ensuring that robust safety protocols are not just in place but are understood and followed. This includes comprehensive education on treatments and their risks, clear guidelines for managing complications, and effective communication and reporting mechanisms within the team.

- Fostering a Culture of Safety: Beyond specific protocols, medical leaders must cultivate a workplace culture where safety is paramount, questions are encouraged, and potential errors can be openly discussed and caught before they lead to harm.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 15, 2005, decision is a sobering reminder of the high standards of care and diligence expected from senior medical professionals in supervisory roles. While teamwork in medicine relies on a distribution of tasks and responsibilities, leaders cannot abdicate their fundamental duty to ensure patient safety. This duty involves proactive engagement in the planning of risky treatments, meticulous oversight of their execution, and the establishment of comprehensive systems to manage known complications. In this case, the confluence of a rare disease, an unfamiliar treatment, a basic but catastrophic reading error, and failures in supervisory oversight led to a patient's death and the criminal conviction of a department head, underscoring that leadership in medicine is a profound and active responsibility.