Lawyer, Auditor, Company Counsel? Navigating Dual Roles in Japanese Corporate Litigation

Case: Action for Change of Share Certificate Denominations and Issuance of True Share Certificates

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of February 18, 1986

Case Number: (O) No. 223 of 1985

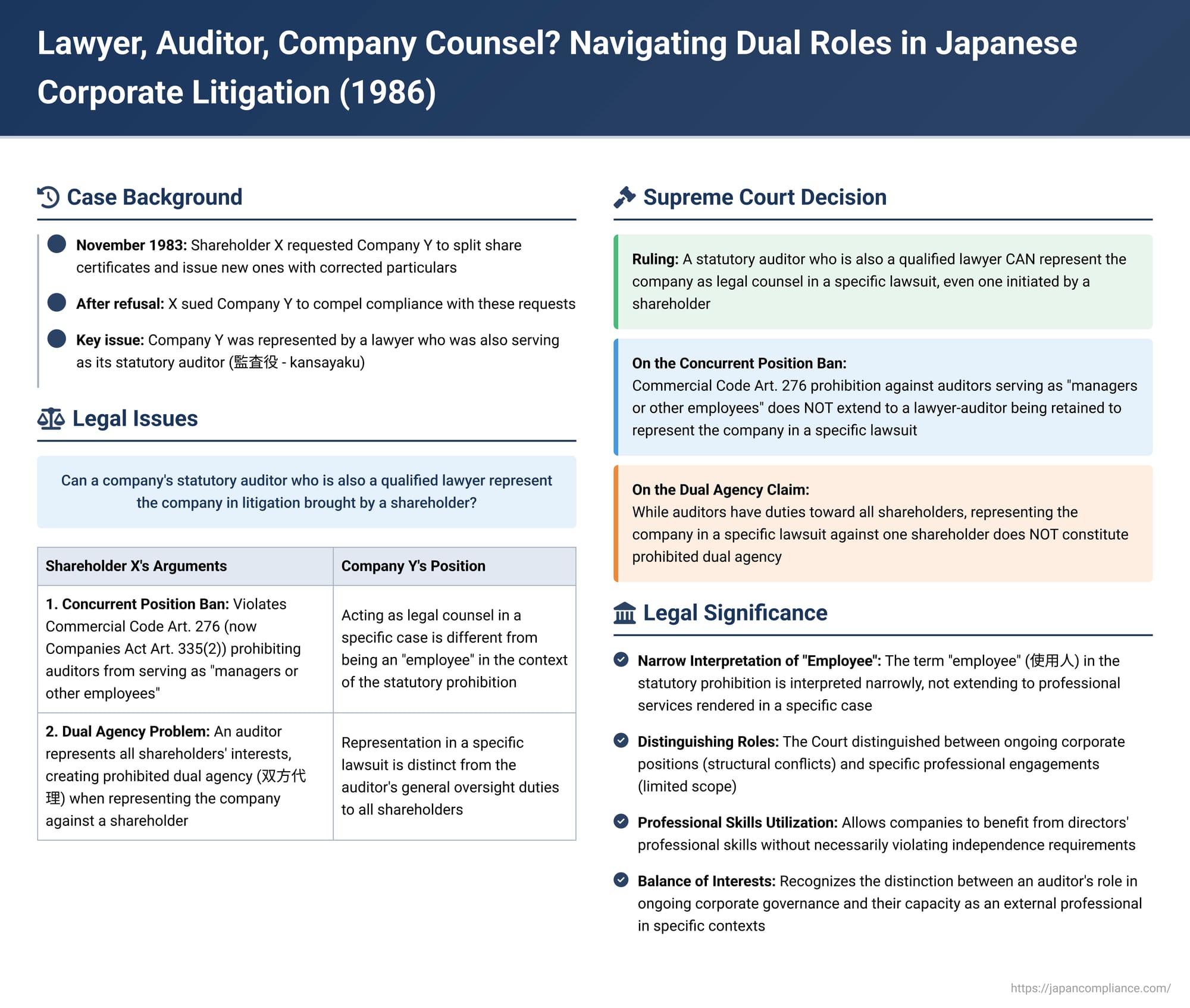

The statutory auditor (監査役 - kansayaku) in a Japanese stock company plays a crucial role in corporate governance, primarily by auditing the company's financial statements and overseeing the conduct of its directors. To ensure their independence and objectivity, the Companies Act (and its predecessor, the Commercial Code) imposes restrictions on auditors holding concurrent positions within the company, such as being a director or an employee. This raises an interesting question: if an auditor is also a qualified lawyer, can they represent the company as its legal counsel in a lawsuit, particularly when that lawsuit is brought against the company by one of its own shareholders? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this issue in a significant judgment on February 18, 1986.

A Shareholder's Claim and a Dual-Hatted Lawyer: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, X, was a shareholder of Company Y. In November 1983, X made several requests to Company Y concerning share certificates. Specifically, X asked the company to:

- Split two existing 1000-share certificates into twenty 100-share certificates.

- Recall the existing certificates due to alleged errors in their recorded particulars (記載事項 - kisai jikō) and issue new, corrected share certificates.

When Company Y did not comply with these requests (except, eventually, for the share splitting), X filed a lawsuit to compel the company to act. The court of first instance (Kobe District Court) and the appellate court (Osaka High Court) largely dismissed X's claims, granting only the request for the change in share certificate denominations.

X appealed to the Supreme Court, raising several grounds. One of the key arguments on appeal concerned a procedural impropriety: the lawyer who had represented Company Y in both the first and second instance court proceedings was also serving as a statutory auditor of Company Y. X contended that this dual role was improper for two main reasons:

- Violation of the Ban on Concurrent Positions: X argued that this situation violated Article 276 of the then-Commercial Code (a provision substantially similar to Article 335, Paragraph 2 of the current Companies Act). This article prohibited a statutory auditor from concurrently serving as a director or as a "manager (shihainin) or any other employee" (支配人その他の使用人 - shihainin sono ta no shiyōnin) of the company or its subsidiaries. X's position was that a lawyer acting as the company's retained legal counsel in a lawsuit effectively assumes a role akin to that of an "employee" or, at least, a position of dependency that compromises the auditor's independence.

- Prohibited Dual Agency: X further argued that a statutory auditor, by nature of their role, represents the interests of all shareholders. Therefore, for an auditor to also act as the company's legal counsel in a lawsuit initiated by a shareholder against the company constituted a form of prohibited "dual agency" (双方代理 - sōhō dairi), where one person attempts to represent two parties with conflicting interests.

The Supreme Court's Stance: Representation Deemed Permissible

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal. In doing so, it rejected X's arguments concerning the impropriety of Company Y's lawyer-auditor acting as its legal counsel in the lawsuit.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Interpreting the Scope of Prohibitions

The Supreme Court provided distinct reasoning for each of X's contentions:

- Regarding the Prohibition on Auditors Holding Concurrent Positions (Commercial Code Art. 276 / Companies Act Art. 335(2)):

The Court held that the statutory provision preventing an auditor from concurrently serving as a director, manager, or other employee of the company or its subsidiaries does not extend so far as to prohibit a qualified lawyer, who also happens to be an auditor of the company, from being retained by that company to act as its legal representative in a specific lawsuit.

The Court's interpretation suggests a distinction between holding an ongoing status within the company that implies subordination or executive function (like being a director or a regular employee) and undertaking a specific professional engagement as external legal counsel for a particular piece of litigation. - Regarding the Allegation of Dual Agency:

The Court acknowledged the appellant's point that a statutory auditor is indeed appointed by the shareholders' meeting, their relationship with the company is governed by the principles of mandate (委任 - inin), and they are expected to exercise their powers and fulfill their duties for the benefit of the company and, by extension, all of its shareholders. Furthermore, the law (then-Commercial Code Article 275-4) specifically provided that in lawsuits between a director and the company, the auditor represents the company.

However, the Supreme Court concluded that these principles do not automatically mean that when a qualified lawyer, who is also an auditor, is retained by the company to act as its legal counsel in a specific lawsuit filed by an individual shareholder against the company, this constitutes prohibited dual agency.

The implication here is that the auditor, when acting as retained legal counsel in such a specific litigation context, is primarily fulfilling a mandate from the company to defend its interests in that particular dispute. This specific role was not seen by the Court as inherently creating an impermissible conflict with their broader duties as an auditor owed to the collective body of shareholders, at least not to the extent of constituting dual agency in that lawsuit.

Analysis and Implications: Auditor Independence and Professional Roles

This 1986 Supreme Court decision offers important, albeit specific, guidance on the interpretation of auditor independence rules in Japan.

- The Purpose of Auditor Independence Rules (Companies Act Art. 335(2)):

The primary objective of prohibiting auditors from concurrently holding positions such as director or employee is to safeguard their independence and ensure they can perform their oversight functions objectively. The core concern is to prevent "self-audit" – a situation where the auditor might be reviewing their own actions or the actions of individuals to whom they are subordinate. As one legal commentary aptly puts it, "if the one who audits and the one who is audited are the same, the audit cannot be effective." This concern applies whether the auditor is concurrently a director, an executive officer, or an employee who is part of the company's operational hierarchy.

The Supreme Court's decision in this case seems to draw a line between an auditor holding an ongoing status or position within the company that implies a structural conflict or dependence, and an auditor undertaking a specific, limited professional engagement like representing the company in a particular lawsuit. - Interpreting "Employee" (使用人 - shiyōnin) in the Context of Auditor Independence:

The term "employee" in Article 335, Paragraph 2 is generally understood to be broader than just individuals with formal employment contracts or significant representative authority (like a shihainin, or manager). It can encompass individuals who, in fact, operate in a position of subordination to the company's executive management or are deeply integrated into its operational functions.

This has led to considerable debate regarding, for example, whether a company's long-term "consulting lawyer" (顧問弁護士 - komon bengoshi) should be considered an "employee" for the purpose of this prohibition if they also serve as an auditor.- Some legal scholars argue that a continuous advisory relationship, especially if the lawyer derives significant income from it or is perceived as being closely aligned with management, can create a de facto dependency that compromises the necessary independence for an auditor.

- Others contend that a lawyer, by virtue of their professional ethics and duties, can maintain independence even in a long-term advisory role, and thus should not automatically be classified as an "employee" whose auditor role would be invalidated. (The Supreme Court briefly touched upon the status of a consulting lawyer in a 1989 decision, but this 1986 case is more focused).

The 1986 Supreme Court decision, however, specifically addressed the scenario of an auditor-lawyer acting as counsel in a particular lawsuit. The Court appeared to view this as distinct from a general, ongoing "employee" status or a comprehensive consulting role that might more readily suggest subordination to the company's management.

- The Nature of Legal Representation in a Specific Case:

The Supreme Court's ruling implies that acting as external legal counsel for a defined piece of litigation is primarily a professional service rendered to the company, rather than an assumption of an internal corporate "position" that inherently conflicts with the auditor's oversight role.

The argument often made in favor of allowing lawyers to serve as auditors, even if they have some form of advisory relationship with the company, is that their professional ethics (e.g., under the Lawyer Act Article 25 and the Japan Federation of Bar Associations' Basic Rules of Lawyer's Duties Articles 27 and 28, which govern conflicts of interest) provide a safeguard. These ethical rules require lawyers to avoid situations where their duties to one client conflict with their duties to another, or with their own interests.

However, legal commentary points out that compliance with a lawyer's professional ethics, while important, does not automatically equate to satisfying the structural independence requirements that company law imposes on statutory auditors. The aims of professional legal ethics and company law's auditor independence rules, though overlapping, are not identical. Relying solely on professional ethics might not always address the company law's concern about potential structural or perceived lack of independence for an auditor who is also, for example, the company's long-standing general counsel.

Nevertheless, for the more limited engagement of representing the company in a specific lawsuit, the Supreme Court in 1986 found that this did not trigger the statutory prohibition. The Court seems to have concluded that the risk of such a specific retainer fatally compromising the auditor's overall objectivity and independence in performing their statutory audit duties was not sufficiently direct or substantial to warrant a ban. - The Dual Agency Argument:

The plaintiff's argument that the lawyer-auditor representing the company against a shareholder constituted prohibited dual agency was also rejected. While it's true that auditors are elected by shareholders and have a broad duty to act in the interest of the company, which in turn encompasses the collective interests of all shareholders, the Supreme Court did not see this as creating an automatic dual agency problem in this specific litigation context.

When a single shareholder sues the company, the company has a right to defend itself. The auditor, in their capacity as retained legal counsel for that specific suit, is acting upon the company's instructions to represent its interests in that litigation. This specific role is distinct from their broader statutory duties as an auditor overseeing management on behalf of all shareholders. The interests of one shareholder engaged in litigation against the company are not necessarily identical to, and can even conflict with, the interests of the shareholder body as a whole or the company as an entity, which the auditor must also consider in their audit capacity. The Court implicitly found that these roles could be managed without necessarily creating an impermissible conflict of dual agency in the lawsuit itself. - The "Sitting Well" Problem – A Deeper Look at the Auditor's Role:

Some legal commentary delves into the theoretical underpinnings of the auditor's role within the corporate governance structure, sometimes referring to the "awkward fit" or "sitting well" problem (座りの悪さ - suwari no warusa) of the statutory auditor. This refers to the unique and somewhat hybrid nature of the auditor's function, especially concerning "operational audits" (業務監査 - gyōmu kansa), which can involve assessing the appropriateness and legality of directors' business decisions.

If an auditor's role extends too far into evaluating the substantive business judgment of directors, it begins to resemble the decision-making and oversight functions of the directors themselves. The prohibition against an auditor concurrently serving as a director (Companies Act Art. 335(2)) is seen as fundamental to maintaining a clear conceptual and functional separation between the executive/managerial role of directors and the oversight role of auditors.

The prohibition against auditors also being "employees," on the other hand, is often viewed less as a fundamental structural separation of distinct corporate organs and more as a practical rule aimed at preventing direct subordination and ensuring impartiality – essentially, avoiding even the appearance of impropriety (often likened to the proverb, "Do not adjust your cap under a plum tree" – 李下に冠を正さず - rika ni kanmuri o tadasazu – to avoid suspicion of stealing plums).

In this context, the Supreme Court's 1986 decision seems to have viewed the specific act of a lawyer-auditor representing the company in a single lawsuit as not creating the kind of ongoing, status-based dependency or inherent conflict that the prohibition against being an "employee" or "director" primarily aims to prevent.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of February 18, 1986, provides an important clarification regarding the professional engagements of statutory auditors who are also qualified lawyers. It establishes that such an individual is not, by virtue of their dual roles, automatically barred from representing the company as its legal counsel in a specific lawsuit, even when that lawsuit is initiated by a shareholder against the company. The Court determined that this specific form of legal representation does not fall within the intended scope of the statutory prohibition against auditors concurrently serving as company "employees," nor does it inherently constitute a prohibited instance of dual agency. This decision offers a degree of flexibility, recognizing that an auditor's professional legal skills can be utilized by the company in litigation without necessarily compromising the core principles of auditor independence, provided the engagement is for a specific, defined matter.