Lapse Without Warning? Japanese Supreme Court on Insurance 'No-Notice Lapse Clauses' and Consumer Protection

Date of Judgment: March 16, 2012

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. 332 (Ju) of 2010 (Claim for Confirmation of Existence of Life Insurance Contracts)

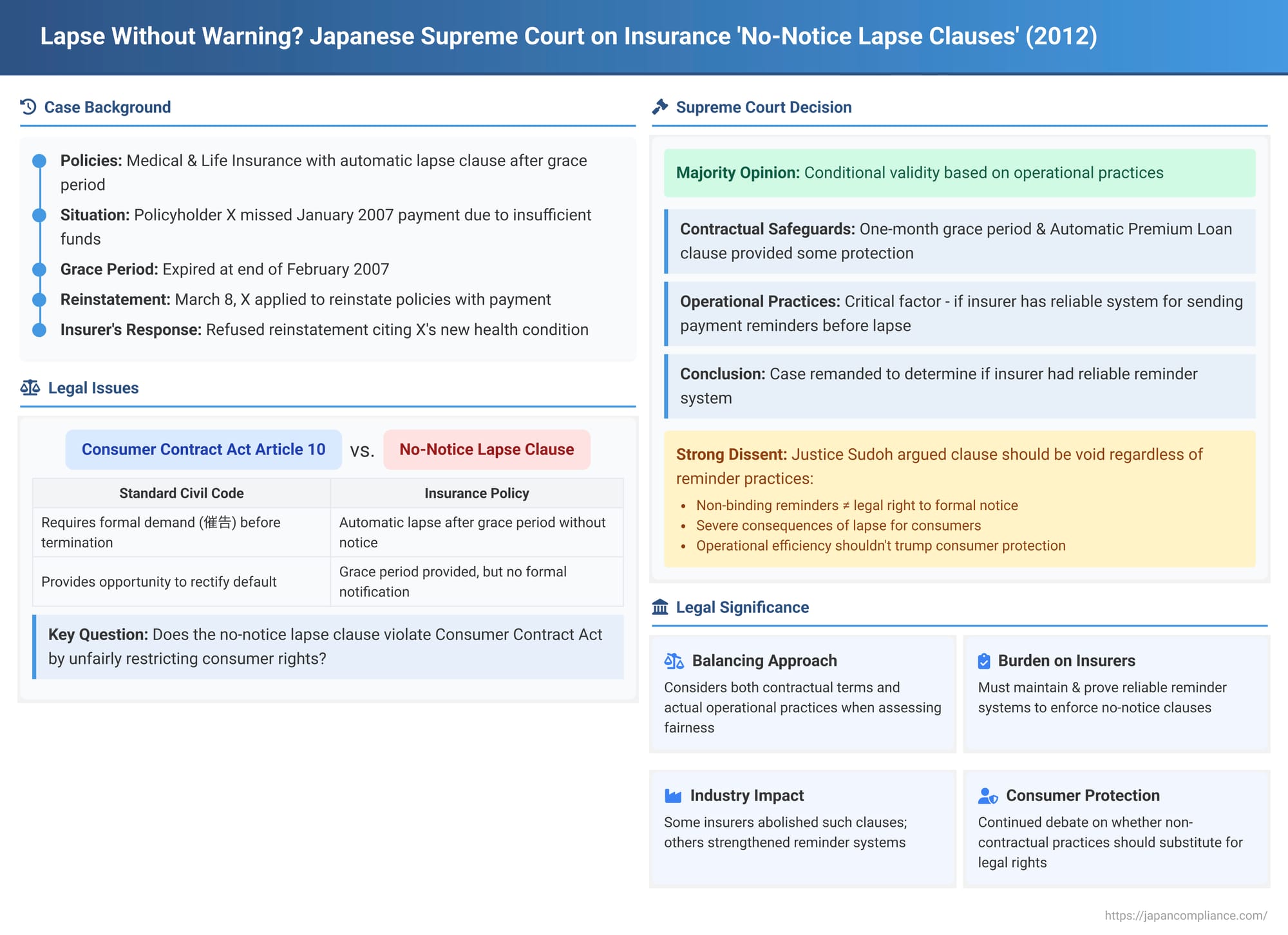

Insurance policies often contain clauses stipulating that the policy will automatically lapse if premiums remain unpaid after a specified grace period, without requiring the insurer to issue a formal demand for payment (a "no-notice lapse clause," or musaikoku shikkō jōkō). While such clauses may offer operational efficiencies for insurers, they can pose significant risks for consumers who might inadvertently miss a payment. The validity of these clauses under Japan's Consumer Contract Act (CCA) was the central issue in a pivotal Supreme Court decision on March 16, 2012.

The Policyholder's Predicament: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, X, a "consumer" as defined by the Consumer Contract Act, had entered into a medical insurance contract and a life insurance contract with Y, the insurer. X was both the policyholder and the insured. The terms and conditions of these policies stipulated that after the initial payment, premiums were due monthly and were to be paid via bank account transfer during a "payment month" (the calendar month corresponding to the policy's anniversary date).

The policies included several key clauses:

- The Lapse Clause (本件失効条項 - honken shikkō jōkō): If a premium was not paid within the payment month, a grace period would extend from the first day to the last day of the following month. If the premium remained unpaid by the end of this grace period, the insurance contract would automatically lose its validity (lapse) from the day immediately following the end of the grace period.

- Automatic Premium Loan (APL) Clause: Even if premiums were unpaid during the grace period, if the total amount of overdue premiums plus interest did not exceed the policy's cash surrender value (CSV), the insurer would automatically loan the premium amount to the policyholder, applying it to the due premium and thereby keeping the policy in force.

- Reinstatement Clause: If a policy lapsed, the policyholder could apply to have it reinstated with Y's approval within one year for the medical insurance policy, or three years for the life insurance policy.

Notably, the medical insurance policy had no cash surrender value, and the life insurance policy, according to its terms, also had no cash surrender value for the first two years of the contract.

X failed to pay the premium for January 2007 due to insufficient funds in the designated bank account. This non-payment continued through the grace period, which ended on the last day of February 2007. On March 8, 2007, X applied to Y for the reinstatement of both policies, offering to pay the overdue premiums for January through March. However, Y refused to approve the reinstatement, citing, among other reasons, that X had been diagnosed with idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head around July 2006 (a new health condition arising after policy inception but before the lapse).

X subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking confirmation from the court that the insurance contracts were still in existence and valid. Y countered that the contracts had lapsed at the end of February 2007 due to non-payment of premiums, in accordance with the no-notice lapse clause.

The court of first instance ruled against X, upholding the validity of the lapse clause. However, the High Court, on appeal, reversed this decision, finding the lapse clause void under Article 10 of the Consumer Contract Act and ruling in X's favor. Y Insurance Company then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Battleground: CCA Article 10 vs. Standard Insurance Terms

The core legal issue revolved around Article 10 of Japan's Consumer Contract Act. This article is designed to protect consumers from unfair contract terms. It declares void any clause in a consumer contract that restricts the rights of a consumer or expands the obligations of a consumer, as compared to provisions of the Civil Code or other laws that are not mandatory (i.e., "optional rules"), and which, in violation of the fundamental principle of good faith and trust, unilaterally prejudices the interests of the consumer.

Under the Japanese Civil Code (Article 541 at the time, now Articles 541 and 542 relate to contract termination), if a party fails to perform its obligation, the other party generally must first make a formal demand for performance (a saikoku - 催告), setting a reasonable period for compliance. Only if performance is not rendered within that period can the contract typically be terminated. The no-notice lapse clause in Y's insurance policies bypassed this saikoku requirement, allowing the contract to terminate automatically after the grace period. This was seen as restricting a right X would otherwise have under the Civil Code's default rules, thus bringing Article 10 of the CCA into play.

The Supreme Court's Conditional Green Light

The Supreme Court, in its majority opinion, reversed the High Court's decision (which had found the clause void) and remanded the case for further examination.

Majority Opinion:

The Court acknowledged that a formal demand for performance (saikoku) serves the function of making the defaulting party aware of their non-performance and giving them an opportunity to perform before the contract is terminated. The no-notice lapse clause, by eliminating this step, indeed restricts the consumer's rights compared to the Civil Code's default provisions.

However, the Court then considered several factors:

- The insurance policies clearly stipulated that premiums were due within the "payment month." Lapse did not occur immediately upon non-payment but only if the default was not rectified during a subsequent grace period. This grace period was one month, which the Court noted was longer than the "reasonable period" typically required for a saikoku.

- The presence of the Automatic Premium Loan (APL) clause, where applicable (i.e., if there was sufficient cash surrender value), provided a mechanism to prevent policies with a history of paid premiums from lapsing easily due to a single missed payment. The Court viewed these features as demonstrating a degree of consideration for protecting the policyholder's rights in the event of non-payment.

The most critical part of the Supreme Court's reasoning was its focus on the insurer's actual operational practices:

- The Court stated that if Y Insurance Company, at the time the contracts were concluded, had an established system for sending reminders to policyholders about overdue premiums before the policies lapsed, and if this practice was reliably and consistently carried out, then it could be presumed that policyholders would normally become aware of their non-payment.

- Considering the nature of the insurance business, which involves a large number of contracts, the Court concluded that if the policy terms included protective measures (like the grace period and APL clause) and if the insurer reliably implemented such a reminder system, then the no-notice lapse clause would not be deemed to unilaterally prejudice the consumer's interests in violation of the principle of good faith, as prescribed by Article 10 of the CCA.

Because the High Court had not sufficiently examined whether Y actually had such a reliable operational practice for reminders, the Supreme Court remanded the case for this factual determination. (The remanded High Court subsequently found that Y's reminder system was reliably operated and upheld the lapse clause's validity ).

A Strong Dissent: Prioritizing Consumer Rights

Justice Sudoh Masahiko issued a strong dissenting opinion, arguing that the no-notice lapse clause should be held void under CCA Article 10.

Key points from the dissent included:

- The protections offered by the policy terms (grace period, APL) were insufficient substitutes for the legally guaranteed right to a formal saikoku. A one-month grace period can pass quickly, and if the consumer is unaware of the missed payment (e.g., due to an oversight in bank balance), the actual time they have to rectify the situation after receiving a non-binding reminder might be very short.

- The APL clause is meaningless if the policy has no cash surrender value, or insufficient CSV, as was the situation for X's policies at the time of the missed payment.

- Most importantly, a mere factual practice of sending reminder notices, however consistently performed, is not a legal obligation stipulated in the contract. The insurer could change or cease this practice, for instance, due to cost-cutting measures, leaving consumers without even this informal protection. Such a non-guaranteed practice cannot be equated with the legal right to receive a formal saikoku.

- The consequences of policy lapse are often devastating for consumers, particularly if their health has deteriorated, making it difficult or impossible to obtain new insurance coverage. The insurer's pursuit of operational efficiency and cost reduction should not come at the expense of such fundamental consumer protection.

- Justice Sudoh suggested that, at a minimum, insurers should be legally obligated, through the policy terms themselves, to send proper reminder notices that clearly warn of impending lapse.

Unpacking the Majority's Rationale

The Supreme Court's majority decision sought a balance. It did not give a blanket approval to all no-notice lapse clauses, nor did it condemn them outright. Instead, it hinged the validity of such clauses on a combination of:

- Contractual Safeguards: The existence of terms within the policy itself that offer some measure of protection, such as a clearly defined (and reasonably long) grace period and mechanisms like APL where feasible.

- Reliable Operational Practices: Crucially, the insurer's proven, consistent, and reliable system of notifying policyholders about overdue payments before the policy actually lapses.

The underlying idea is that if a consumer is made aware of their default and given a reasonable opportunity to cure it, the core function of a formal saikoku is effectively fulfilled, even if the awareness comes through a systematic but non-contractual reminder rather than a legally mandated demand.

Legal commentary prior to this decision was divided, with some arguing for the general validity of such clauses (especially if reminder practices were in place) and others deeming them contrary to consumer protection principles. The Supreme Court's decision was notable for explicitly incorporating the insurer's actual operational practices into the assessment under CCA Article 10, a point on which the original High Court had taken a different view.

Implications and Developments

The Supreme Court's 2012 ruling has had several important implications:

- Emphasis on "Reliable Operational Practice": It places a burden on insurers who use no-notice lapse clauses to demonstrate that they have robust and consistently applied systems for reminding policyholders of missed payments. The mere existence of a policy to send reminders may not be enough; its effective and reliable implementation is key.

- Nuanced Validity: The decision means that the validity of a no-notice lapse clause is not determined in a vacuum but is assessed based on the totality of circumstances, including both the written terms of the policy and the insurer's real-world conduct.

- Insurer Practices: In response to this and other legal developments, some insurance companies in Japan, like Nippon Life, reportedly moved to abolish no-notice lapse clauses and automatic premium loan provisions in their standard policies, opting instead for systems involving formal saikoku and subsequent notice of termination. Other insurers, however, appear to continue using clauses similar to the one in this case, presumably prepared to defend their reminder systems if challenged.

- Relevance to Broader Contract Law: The Court's approach of considering operational practices when assessing the fairness of a standard term under CCA Article 10 may also inform how similar issues are treated under other legal provisions, such as Article 548-2, paragraph 2 of the revised Civil Code, which deals with the incorporation and validity of standard contract terms ("定型約款" - teikei yakkan). This provision also involves an assessment of whether a term unilaterally harms the other party's interests in light of "the circumstances of the standard transaction and its actual conditions".

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2012 decision on no-notice lapse clauses in insurance contracts attempts to strike a balance between the operational needs of insurers dealing with numerous small premium payments and the protection of consumers from unexpected policy termination. By making the validity of such clauses conditional on the insurer's demonstrable and reliable reminder practices, in addition to certain contractual safeguards, the Court avoided a categorical ruling. However, this conditional approach means that the protection afforded to consumers can depend significantly on the insurer's internal systems and their proven consistency, rather than solely on clearly defined contractual rights. The strong dissenting opinion serves as a reminder of the ongoing debate about the extent to which non-contractual practices should substitute for legally enshrined consumer protections, especially when fundamental interests like insurance coverage are at stake.