Landmark Ruling on Collective Agreements and Non-Union Employees: The Y Inc. Case (Supreme Court of Japan, March 26, 1996)

Case Name: Claim for Confirmation of Status, etc.

Court: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: (O) No. 650 of 1993

Date of Judgment: March 26, 1996

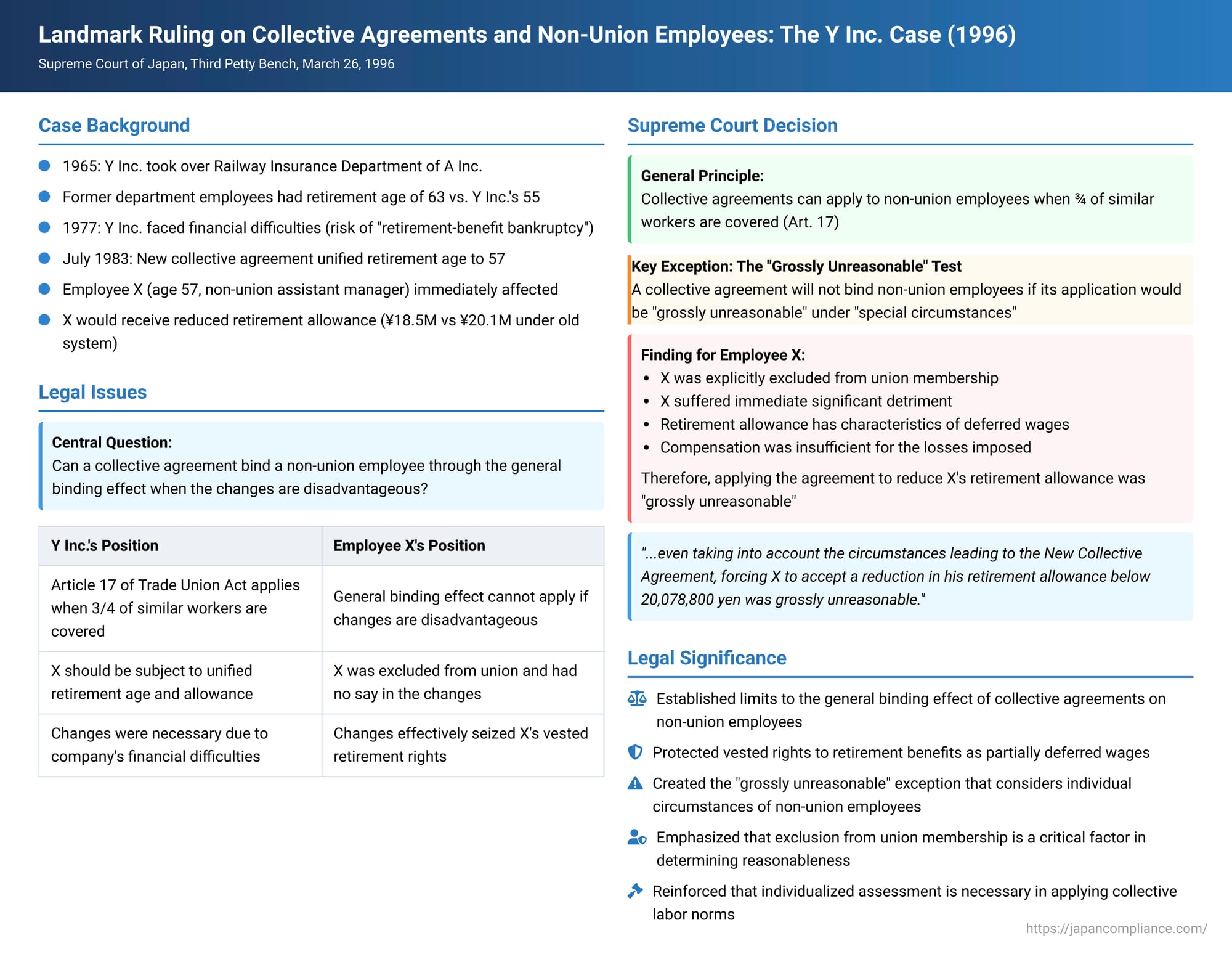

This case, decided by the Supreme Court of Japan, delves into the complex interplay between collective labor agreements, company work rules, and the rights of non-union employees, particularly concerning changes to fundamental working conditions like retirement age and severance pay.

I. Factual Background

The case revolves around Mr. X, an employee whose employment journey involved several transitions and evolving contractual terms.

- Initial Employment with A Inc.: On June 1, 1951, Mr. X was hired as an employee of the Railway Insurance Department of A Inc. The terms and conditions for employees in this department were determined by the Head of the Railway Insurance Department. These were set out in the "Railway Insurance Department Work Rules" (hereinafter "Department Work Rules") and a collective labor agreement concluded between the Department Head and the All Japan Non-Life Insurance Labor Union, Railway Insurance Branch (hereinafter "Department Collective Agreement"). Under these provisions, the mandatory retirement age for department employees was 63.

- Transfer to Y Inc.: On February 1, 1965, Y Inc. (the appellant) took over the insurance business previously handled by A Inc.'s Railway Insurance Department. Consequently, Mr. X and other employees of the department had their employment contracts with A Inc. consensually terminated and entered into new employment contracts with Y Inc.At that time, Y Inc. already had its own established work rules and a collective agreement with its own union, the All Japan Non-Life Insurance Labor Union, Y Inc. Branch. However, there was no immediate agreement on unifying these existing rules and agreements with those of the former Railway Insurance Department. It was mutually understood that, pending such unification, the Department Work Rules would retain their legal normative effect, and the Department Collective Agreement would continue to have its prescribed effect under the Trade Union Act.

- Union Merger and Negotiations for Unification: After the former Railway Insurance Department employees joined Y Inc., their union branch merged with Y Inc.'s existing union branch, forming a single union (hereinafter "the Union"). Y Inc. and the Union engaged in ongoing negotiations to unify the working conditions of the former Railway Insurance Department employees and other employees. Over time, by 1972, they successfully unified conditions related to working hours, retirement benefits, and wage systems. However, the unification of the retirement age remained an unresolved issue. Former Railway Insurance Department employees retained a retirement age of 63, while other employees had a retirement age of 55.

- Y Inc.'s Financial Difficulties and the New Collective Agreement: In 1977, Y Inc. faced a deteriorating financial situation. The increasing cost of retirement benefits was a contributing factor, and an inspection by the Ministry of Finance indicated a risk of "retirement-benefit bankruptcy" if the situation persisted.Against this backdrop, Y Inc. prioritized the unification of retirement ages as a crucial measure for corporate restructuring. During wage negotiations in fiscal 1979, the company proposed revisions to its personnel and retirement benefit systems, including the unification of the retirement age. After extended negotiations, Y Inc. and the Union reached a verbal agreement on May 9, 1983, regarding the unification of retirement ages and changes to the retirement benefit calculation rates. This agreement was formalized in writing as the "New Collective Agreement" on July 11, 1983, backdated to May 9, 1983.Concurrently with the New Collective Agreement, Y Inc., on July 11, 1983, amended its work rules (specifically Article 55 concerning retirement) and its Retirement Allowance Regulations to align with the New Collective Agreement. It also newly established Special Employee Regulations and Special Employee Salary Regulations, all of which were communicated to the employees. Notably, an interim agreement made in fiscal 1979 to freeze the base amount for calculating retirement benefits at the fiscal 1978 basic salary level (pending a new agreement on revising the Retirement Allowance Regulations) was terminated with the conclusion of the New Collective Agreement.

- Key Terms of the New Collective Agreement Affecting Mr. X:

- (a) Retirement Age and Re-employment:

- Effective April 1, 1983, the retirement age was set at 57.

- Employees wishing to continue working after retirement and in good health would, in principle, be re-employed as "special employees" until age 60, with one-year contract renewals.

- Salary for special employees would be governed by the Special Employee Salary Regulations.

- Retirement allowance would be paid at the age of 57, with no further payments thereafter.

- (b) Transitional Measures for Retirement Age Unification (as of April 1, 1983):

- For employees aged 57 or older: Re-employment as special employees until age 62. Retirement allowance would be paid based on their basic salary as of March 31 of that year, calculated using a new formula, with no further payments.

- For employees aged 57 or older but under 60: The Special Employee Salary Regulations would apply from fiscal 1983. For those aged 60 and above, their salary (special employee salary, additional pay, and fixed additional pay) would be 70% of their salary at age 60, with other allowances as per the Special Employee Salary Regulations.

- (c) Revision of Retirement Benefit System:

- The standard payment rate in the Retirement Allowance Regulations was changed from "71 months' salary for 30 years of service" to "51 months' salary for 30 years of service."

- The base amount for calculating retirement benefits from fiscal 1983 onwards would be the full amount of basic salary (personal pay and job-grade pay) stipulated for each employee from April 1, 1983.

- (d) Transitional Measures for Retirement Benefit System Revision (for employees with 30+ years of service): A three-year transitional period for the standard payment rate:

- Fiscal 1983: 60 months

- Fiscal 1959: 57 months

- Fiscal 1960: 54 months

- (e) Compensation Payment:

- Y Inc. agreed to pay a compensatory sum to all eligible employees to address the changes in retirement age, unification, and retirement allowance regulations. This amounted to an average of 120,000 yen per person (a lump sum of 70,000 yen plus an average of 50,000 yen). Eligible employees were those on the payroll as of April 1, 1983, excluding 7 new hires in fiscal 1983 and other ineligible employees, totaling 762 individuals.

- For former Railway Insurance Department employees: Those aged 50 or older as of April 1, 1983 (22 individuals) received an additional 300,000 yen. Those under 50 (49 individuals) received an additional 100,000 yen.

- (f) Supplementary Provisions:

- The agreement was effective from April 1, 1983.

- Parts of previous agreements conflicting with this new agreement would lose their effect.

- (a) Retirement Age and Re-employment:

- Special Employee Salary Regulations: These stipulated, among other things:

- For "specialist/general staff" special employees, monthly salary would be a combination of special employee salary and various allowances.

- Special employee salary was set at 60% of the sum of personal pay and functional pay at the time of retirement.

- Certain allowances (family, skills, Hokkaido posting, housing, separation, remote work, heating) were 100% of the regular employee rates, while additional pay and fixed additional pay were 60%.

- Salary was paid from the month following becoming a special employee.

- No salary increases for special employees, except for general base pay increases applicable to regular employees.

- Mr. X's Situation: As of April 1, 1983, Mr. X was an Assistant Manager in charge of sales at Y Inc.'s Kitakyushu branch and had already reached the age of 57. He performed insurance sales duties under the direction of the branch manager, who was a union member. However, the collective agreement between Y Inc. and the Union stipulated that assistant managers were non-union members, and thus Mr. X was excluded from union membership. At the Kitakyushu branch, three-fourths of the regularly employed workers were union members.

- Y Inc.'s Actions: Y Inc. believed that the New Collective Agreement and the associated changes to work rules (including retirement allowance, special employee, and special employee salary regulations) would retroactively alter Mr. X's employment conditions from April 1, 1983.

- Anticipating this, from May 1983, Y Inc. paid Mr. X only the salary stipulated under the Special Employee Salary Regulations.

- For the April 1983 salary, which had already been paid based on the regular employee salary regulations, Y Inc. deducted the difference (between the regular and special employee salary) from Mr. X's June 1983 bonus, treating it as an overpayment.

- Y Inc. treated Mr. X as having retired at the end of March 1983. His retirement allowance was calculated as his basic salary on that date (308,400 yen) multiplied by 60 (as per the transitional measures for fiscal 1983), totaling 18,504,000 yen.

- Mr. X's basic salary in fiscal 1978 was 282,800 yen. Multiplied by the pre-amendment retirement allowance rate of 71, this would have yielded 20,078,800 yen. The difference between this amount and the sum Y Inc. paid was 1,574,800 yen.

Mr. X challenged these actions, leading to the litigation. The lower courts largely sided with Mr. X, and Y Inc. appealed to the Supreme Court.

II. Legal Issues and the Supreme Court's Reasoning

The Supreme Court addressed two main arguments raised by Y Inc.:

- Whether Mr. X's salary from April 1983 should be based on the new Special Employee Salary Regulations due to the retroactive application of the New Collective Agreement and revised work rules.

- Whether Mr. X's retirement allowance should be calculated according to the New Collective Agreement and the revised Retirement Allowance Regulations.

A. Retroactive Application of Salary Changes (Point 2 of Y Inc.'s Appeal)

The Court swiftly dismissed this argument. It noted that the New Collective Agreement and the amendments to the work rules clearly took effect on July 11, 1983. Therefore, from April 1, 1983, to July 10, 1983, Mr. X continued to work in his existing capacity as a regular employee and had already acquired the right to wages calculated according to the pre-existing standards.

The Court affirmed the principle that vested wage claims, i.e., rights to payment for work already performed, cannot be divested or altered by a collective agreement concluded or work rules changed after the work was performed and the wage claim arose. Citing a previous Supreme Court judgment (September 7, 1989, First Petty Bench), it held that Y Inc. was obligated to pay Mr. X his salary as a regular employee until July 10, 1983. The High Court's decision on this point was therefore upheld.

B. Application of the New Collective Agreement and Revised Work Rules to Retirement Allowance (Point 3 of Y Inc.'s Appeal)

This was the core of the dispute, involving the general binding effect of collective agreements on non-union employees and the reasonableness of disadvantageous changes to work rules.

1. General Binding Effect of the Collective Agreement (Trade Union Act, Article 17)

- The Principle: Article 17 of the Trade Union Act provides that when three-fourths or more of the workers of the same kind regularly employed in a factory or workplace come under the application of a single collective agreement, the normative effect of that agreement extends to other workers of the same kind employed in that workplace (the "general binding effect").

The Court acknowledged that Mr. X worked at Y Inc.'s Kitakyushu branch, where the New Collective Agreement met the three-fourths requirement. Therefore, in principle, its terms should apply to him. - Disadvantageous Terms and Overall Context: The Court stated that even if some provisions of a collective agreement are less favorable to non-union employees of the same kind compared to their previous conditions, this alone does not prevent those disadvantageous parts from applying. Collective agreements typically establish working conditions comprehensively, considering various socio-economic factors at the time of negotiation. It is inappropriate to isolate specific parts and label them simply as "advantageous" or "disadvantageous."

Furthermore, the purpose of Article 17 is primarily to unify working conditions within a workplace based on those applicable to the majority (three-fourths) of employees, thereby maintaining and strengthening the union's right to organize and realizing fair and appropriate working conditions. Given this purpose, it is not appropriate to deny the normative effect of a collective agreement simply because some of a non-union employee's prior conditions were more favorable. - The "Grossly Unreasonable" Exception for Non-Union Employees: However, the Court introduced a crucial qualification. Non-union employees are not involved in the union's decision-making processes. Conversely, a union is generally not in a position to actively work to improve the conditions or protect the interests of non-union employees.

Considering these factors, the Court held that if applying a collective agreement to a specific non-union employee would be "grossly unreasonable" under "special circumstances," then the normative effect of that collective agreement cannot be extended to that employee.

The "special circumstances" to be considered include:- The degree and nature of the disadvantage imposed on the specific non-union employee.

- The circumstances leading to the conclusion of the collective agreement (including its necessity).

- Whether the employee in question was eligible for union membership.

- Application to Mr. X's Case:

- Context of the Agreement: The Court acknowledged that Y Inc. had long-standing issues unifying working conditions between former Railway Insurance Department employees and others. The company's financial stability was genuinely threatened by the existing retirement allowance system, necessitating even an interim measure of freezing the calculation base. Thus, the Union's decision to accept the New Collective Agreement, which included some disadvantageous terms for certain employees, was seen as having a reasonable basis, aimed at ensuring employment stability for all union members and achieving balanced overall working conditions. Therefore, a blanket denial of the application of disadvantageous parts of the New Collective Agreement to Mr. X based solely on their partial unfavorability was not appropriate.

- Gross Unreasonableness for Mr. X: Despite the general validity of the agreement, the Court found its application to Mr. X regarding his retirement allowance to be grossly unreasonable.

- Immediate and Significant Detriment: As of July 11, 1983 (the effective date of the New Collective Agreement), Mr. X had already reached 57. Applying the agreement to him meant he was deemed retired on that very day. Simultaneously, his accrued retirement allowance entitlement would be reduced compared to the amount calculated under the previous regulations. He stood to suffer only significant disadvantages from the New Collective Agreement.

- Nature of Retirement Allowance: When retirement allowance conditions are clearly defined in advance (e.g., in retirement allowance regulations), employees acquire a right to a specific amount calculated thereunder upon retirement. Retirement allowance also has characteristics of deferred wages for past labor.

- Impact on Vested Rights: Applying the New Collective Agreement to reduce Mr. X's retirement allowance to an amount less than 20,078,800 yen (calculated using his fiscal 1978 basic salary and the pre-amendment payment rate of 71) was deemed almost equivalent to the Union unilaterally disposing of or altering Mr. X's concretely acquired right to retirement benefits against his will.

- Exclusion from Union Membership: Critically, Mr. X was explicitly excluded from union membership by the terms of the collective agreement between Y Inc. and the Union.

- Conclusion on Unreasonableness: Considering these factors, even taking into account the circumstances leading to the New Collective Agreement, forcing Mr. X to accept a reduction in his retirement allowance below 20,078,800 yen was grossly unreasonable. To that extent, the normative effect of the New Collective Agreement did not extend to him.

- Insufficiency of Compensation: The New Collective Agreement did provide for compensation payments to mitigate the disadvantages arising from the unified retirement age and changes to the retirement benefit calculation. However, the Court found this compensation insufficient for Mr. X. The lowering of the retirement age advanced his retirement by approximately six years. While re-employment was possible, the salary under the "special employee" status was significantly lower. The agreed-upon compensation was inadequate to cover even the economic disadvantages resulting from the earlier retirement, let alone justify the reduction of his retirement allowance below the previously calculated sum.

- Unification Argument Not Persuasive Here: Y Inc. argued that the changes were part of a process of unifying working conditions, where former Railway Insurance Department employees had previously seen favorable changes. The Court rejected this for the retirement allowance calculation. The retirement allowance calculation method had already been unified for both groups of employees before 1972. The changes to the retirement allowance calculation in the New Collective Agreement were driven by separate managerial necessities, not by the goal of unifying disparate systems. Therefore, this history did not alter the conclusion about the unreasonableness of the reduction for Mr. X.

2. Reasonableness of Changes to Work Rules (Retirement Allowance Regulations)

- The Principle: The Court reiterated the established legal principle that when work rules are changed to the disadvantage of employees, such changes are only legally binding if they are "reasonable." Reasonableness is judged by considering both the necessity for the change and the content of the change, particularly in light of the degree of disadvantage suffered by the employees. (Citing Supreme Court, Grand Bench, December 25, 1968, and Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, February 16, 1988).

- Application to Mr. X's Case:

- Necessity for Change: The Court acknowledged a high degree of necessity for Y Inc. to reduce the retirement allowance payment rates to avoid further financial deterioration and to resolve the irregular situation of freezing the calculation base.

- Unreasonableness of Content for Mr. X: However, in conjunction with the lowering of the retirement age through the work rule changes, the effect on Mr. X – who was deemed retired on the day the changes took effect (July 11, 1983) – was that his retirement allowance would be reduced below 20,078,800 yen. This specific outcome, regarding the content of the change as applied to him, was found to lack the reasonableness required to be legally normative. This was clear from the reasoning provided in the discussion of the collective agreement's general binding effect.

- Conclusion on Work Rules: Therefore, to the extent that the revised Retirement Allowance Regulations would reduce Mr. X's payable retirement allowance below 20,078,800 yen, they could not be recognized as effective against him.

III. Conclusion of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment, which had ruled in favor of Mr. X on these points, to be justifiable. Y Inc.'s arguments, based on its own interpretation of the law, were not accepted.

Therefore, the appeal by Y Inc. was dismissed. The appellant, Y Inc., was ordered to bear the costs of the appeal.

IV. Key Takeaways

This judgment underscores several critical aspects of Japanese labor law:

- Protection of Vested Rights: Rights to wages already earned for past labor are strongly protected and generally cannot be retroactively diminished by subsequent changes to collective agreements or work rules.

- General Binding Effect of Collective Agreements (Article 17, Trade Union Act): While a collective agreement covering three-fourths of similar employees generally extends to non-union employees, this is not absolute.

- "Grossly Unreasonable" Exception: The normative effect of a collective agreement will not apply to a non-union employee if its application would be "grossly unreasonable" under "special circumstances." Key factors include the extent of the disadvantage, the background of the agreement, and, significantly, the employee's eligibility (or lack thereof) for union membership. Exclusion from union decision-making processes and representation is a vital consideration.

- Reasonableness of Disadvantageous Changes to Work Rules: Unilateral changes to work rules by an employer that disadvantage employees are only valid if they are objectively reasonable. This involves a balancing act, weighing the employer's need for the change against the nature and extent of the detriment to the employees. Even if a general need is high, the specific application and content of the change must still be reasonable for affected individuals.

- Individualized Assessment: The case demonstrates that even if a collective agreement or a change to work rules is generally valid and reasonable for the majority, its application to a specific individual in unique circumstances (like Mr. X, who was near retirement and excluded from the union) can be deemed unenforceable if it leads to an exceptionally unfair outcome.

This ruling provides important guidance on the limits of managerial prerogative and the protective scope of labor law principles when employers seek to modify employment conditions, especially when such changes adversely affect long-serving employees, non-union members, and their accrued benefits.