Landmark "Karoshi-Jisatsu" Ruling: Japan's Supreme Court on Employer Liability for Overwork Suicide (March 24, 2000)

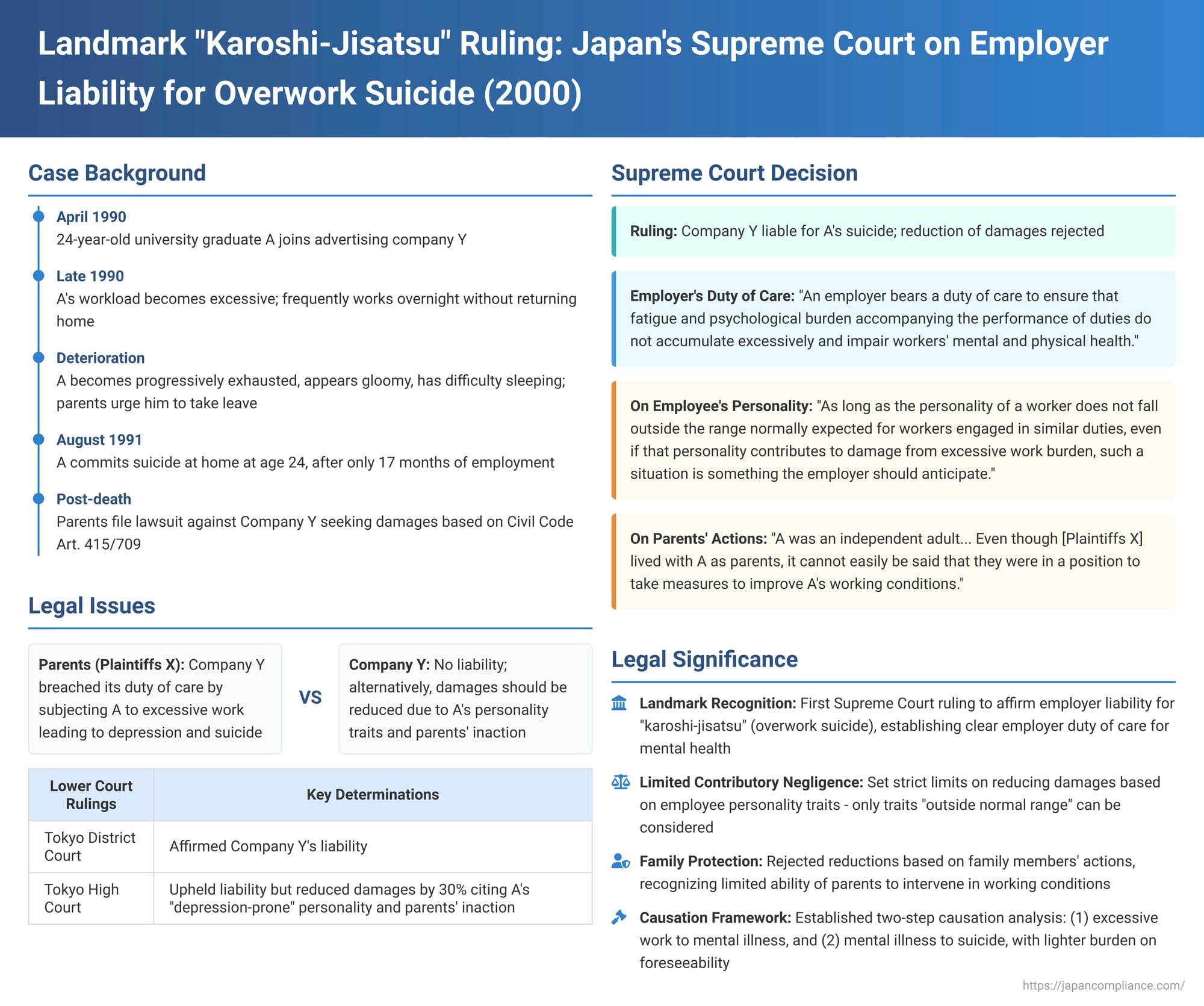

On March 24, 2000, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a groundbreaking judgment in a damages claim case. This ruling was pivotal in establishing employer liability for "karoshi-jisatsu" – suicide resulting from overwork and work-related stress. It clarified the employer's duty of care concerning employee mental and physical health in the face of excessive workloads and set important precedents regarding the application of contributory negligence principles in such tragic circumstances.

The Case of A: A Young Life Overwhelmed by Work

The deceased, A, was a bright and healthy young man who, after graduating from university, joined Company Y, a major advertising agency, in April 1990. He was assigned to the radio promotion department. A was described as athletic, cheerful, honest, responsible, and possessing perfectionist tendencies—qualities generally well-received by superiors and clients. His primary responsibilities involved soliciting corporate sponsorship for radio programs and planning and executing promotional events for these client companies.

Company Y had a prevailing culture of extremely long working hours, and A was no exception. From around late November 1990, A's workload became so immense that he frequently did not return home at night. His parents, Plaintiffs X, grew increasingly concerned about his health and urged him to take paid annual leave, but A felt unable to do so.

A's superiors reportedly instructed him to go home and ensure he got adequate sleep, suggesting that if work remained unfinished, he should come in early the next morning to complete it. Despite these instructions, there was no substantive adjustment or reduction in A's actual workload; in fact, it continued to increase.

Over time, A became progressively physically and mentally exhausted. His demeanor changed; he appeared gloomy and depressed, his complexion was poor, and at times, he seemed unfocused and had difficulty maintaining eye contact. He confided in his superiors, expressing feelings of inadequacy, confusion about his own speech, and an inability to sleep. Tragically, in August 1991, at the age of 24, A took his own life at his home.

A's parents, Plaintiffs X, subsequently filed a lawsuit against Company Y, seeking damages. They argued that A had developed depression as a direct result of the excessively long working hours and overwhelming workload, and that this depression ultimately led to his suicide. Their claim was based on Civil Code Article 415 (breach of contract, specifically the employer's duty of care) and/or Article 709 (tort liability).

The Lower Courts: Liability Affirmed, but Damages Reduced

- Tokyo District Court (First Instance): The District Court affirmed Company Y's liability for A's death.

- Tokyo High Court (Appeal): The High Court also upheld Company Y's liability. However, it significantly reduced the amount of damages payable by 30%. The High Court analogously applied the principle of comparative negligence (or contributory fault, 過失相殺 - kashitsu sōsai) under Civil Code Article 722, Paragraph 2, based on several factors:

- A's perceived "depression-prone" or pre-morbid personality traits.

- Allegations that A had underreported his working hours and had contributed to his situation by mismanaging his time and continuing to work excessively late into the night.

- A's failure to seek professional psychiatric help or to take available paid leave.

- The assertion that A's parents, Plaintiffs X, while being generally aware of A's demanding work situation, had not taken concrete measures to improve it.

Both A's parents (regarding the reduction of damages) and Company Y (regarding the finding of liability) appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding its liability. Crucially, it allowed the appeal from A's parents concerning the reduction of damages, quashing that part of the High Court's decision and remanding the issue of damages back to the High Court for reconsideration without the contested reductions. (A settlement was reportedly reached in the subsequent remand trial.)

I. Establishing the Employer's Duty of Care Regarding Overwork

The Supreme Court laid down a clear foundation for the employer's responsibility:

- "It is well-known that if a worker continues to engage in duties for long hours on working days, leading to excessive accumulation of fatigue and psychological burden, there is a danger of impairing the worker's mental and physical health".

- The Court noted that the Labor Standards Act sets limits on working hours, and Article 65-3 of the Industrial Safety and Health Act stipulates that employers should strive to appropriately manage the work their employees perform, with due consideration for their health. These provisions, the Court reasoned, are aimed at preventing such health dangers from materializing.

- Based on this, the Court concluded: "it is reasonable to conclude that an employer, in assigning duties to its employees and managing these duties, bears a duty of care to ensure that fatigue and psychological burden accompanying the performance of duties do not accumulate excessively and impair the workers' mental and physical health". Furthermore, "Persons with authority to supervise workers on behalf of the employer should exercise their authority in accordance with the content of this employer's duty of care".

II. Affirming Company Y's Liability

The Supreme Court found the High Court's determination of Company Y's liability to be justifiable. The High Court had established a considerable causal link between A's work performance, his subsequent development of depression, and his suicide. It had also found A's superiors to be negligent because they were aware that A was consistently working excessively long hours and that his health was deteriorating, yet they failed to take appropriate measures to alleviate his burden. The Supreme Court endorsed this finding of liability, likely based on Civil Code Article 715 (employer's vicarious liability for the actions of its employees/supervisors).

III. Rejecting Reductions for Contributory Negligence

This was the most groundbreaking part of the judgment. The Supreme Court meticulously addressed and overturned the High Court's reasons for reducing the damages.

- Regarding the Employee's Personality:

- The Court acknowledged the general principle that in personal injury cases, a victim's psychological factors (like personality) that may have contributed to the occurrence or extent of the damage can be considered to a certain extent when determining compensation, based on an analogous application of comparative negligence rules (referencing a prior Supreme Court judgment, Showa 63.4.21). This principle, it stated, applies fundamentally to cases involving harm from excessive work burden as well.

- However, the Court introduced a crucial qualifier: "it goes without saying that the personalities of workers employed by enterprises are diverse. As long as the personality of a specific worker engaged in certain duties does not fall outside the range normally expected for the diversity of individuality among workers engaged in similar duties, even if that personality and the manner of work performance based on it contribute to the occurrence or aggravation of damage suffered by the worker due to an excessive work burden, such a situation is something the employer should anticipate".

- Moreover, employers and their supervisors have the responsibility to assess a worker's suitability for assigned tasks, including considering their personality, when making decisions about job placement and duty assignments.

- Therefore, the Court ruled: "if the worker's personality does not fall outside the aforementioned range, the court, in determining the amount of compensation an employer should pay in a damages claim based on excessive work burden, cannot take into account that personality and the manner of work performance based on it as a psychological factor for reduction".

- Applying this to A's case, the Supreme Court noted that A's personality traits (responsible, perfectionist, etc.) were commonly found among ordinary members of society and had, in fact, been positively viewed by his superiors in relation to his work. Thus, A's personality was not outside the normally expected range. The High Court's decision to reduce damages based on A's personality was therefore deemed an error in legal interpretation and application.

- Regarding the Conduct of A's Parents (Plaintiffs X):

- The High Court had reduced damages on the grounds that A's parents, living with him and aware of his stressful work life, could supposedly have foreseen the tragic outcome and taken steps to improve his working conditions, but had failed to do so.

- The Supreme Court firmly rejected this reasoning: "However, A's said damage resulted from an excessive work burden. A was an independent adult who had graduated from university, became an employee of [Company Y], and engaged in [Company Y]'s duties based on A's own will and judgment. Even though [Plaintiffs X] lived with A as parents, it cannot easily be said that they were in a position to take measures to improve A's working conditions". Under the established facts, the High Court's decision to reduce damages on this basis was also found to be an error in legal interpretation and application.

Key Legal Principles and Impact

The case is a landmark for several reasons:

- First Supreme Court Recognition of Karoshi-Jisatsu Liability: It was the first time Japan's highest court explicitly affirmed an employer's civil liability for damages in a case of "karoshi-jisatsu" (suicide induced by overwork). This provided significant legal backing to claims by families of victims of overwork.

- Defining Employer's Duty of Care for Mental Health: The judgment clearly articulated the employer's duty to take care that an employee's mental and physical health is not impaired by an excessive accumulation of fatigue or psychological stress stemming from their work. This duty is proactive and rooted in general labor law principles and safety legislation.

- Causation and Foreseeability in Overwork Suicides: The Court appeared to accept the established lower court practice of a two-step causation analysis: (1) a causal link between the excessive work and the onset of a mental illness (like depression), and (2) a causal link between the mental illness and the act of suicide. Given that individuals with depression have a statistically higher risk of suicide, if the work-induced mental illness is established, the subsequent link to suicide is often more readily accepted.

Regarding foreseeability, the Supreme Court found it sufficient that A's superiors were aware that he was working to the point of exhaustion (including all-nighters) and that his health was visibly deteriorating. Legal commentary on the case suggests that the employer does not need to foresee the specific outcome of suicide or even clinical depression; rather, foreseeability of a general deterioration in the employee's health due to overwork is likely sufficient to trigger the duty of care. - Strict Limitations on Contributory Negligence: The Court set a high bar for reducing an employer's liability based on the employee's individual characteristics or family actions:

- Personality: An employee's personality traits can only be considered for reducing damages if they are so unusual as to fall outside the "normally expected range of diversity" for workers in similar roles. This significantly limits the "personality defense" for employers.

- Family Conduct: The Court recognized the limited ability of parents or family members to intervene in the working conditions of an independent adult employee.

Broader Impact and the Path Forward

The judgment has had a profound influence on subsequent litigation and administrative practices concerning overwork-related health problems and suicides in Japan. It strengthened the legal basis for holding employers accountable and underscored the importance of proactive measures to manage workloads and protect employee well-being.

The commentary also notes that issues surrounding the privacy of an employee's mental health information can interact with discussions of employer duty and contributory negligence. For example, in a later Supreme Court case (the "Toshiba (Depression) Case," Heisei 26.3.24), where an employer's breach of its safety duty of care was established, the Court did not permit a reduction of damages based on the employee's failure to report hospital visits for mental health issues, citing the highly private nature of such information, particularly when the employee's distress and work impairment were already evident to the employer.

Conclusion: A Resounding Call for Employer Responsibility

The Supreme Court's 2000 ruling in the case was a watershed moment in Japanese labor law. It sent a clear message that employers have a fundamental duty of care to prevent their employees from succumbing to the devastating effects of overwork, including mental illness and suicide. By affirming employer liability for "karoshi-jisatsu" and by strictly limiting the grounds upon which damages could be reduced due to an employee's personality or family actions, the judgment significantly bolstered protections for workers and emphasized the profound responsibility employers bear for the health and safety of their workforce in high-stress, demanding work environments.