Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Resale Price Maintenance: The 1975 Infant Formula Case

Decision Date: July 10, 1975 (Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench)

Introduction

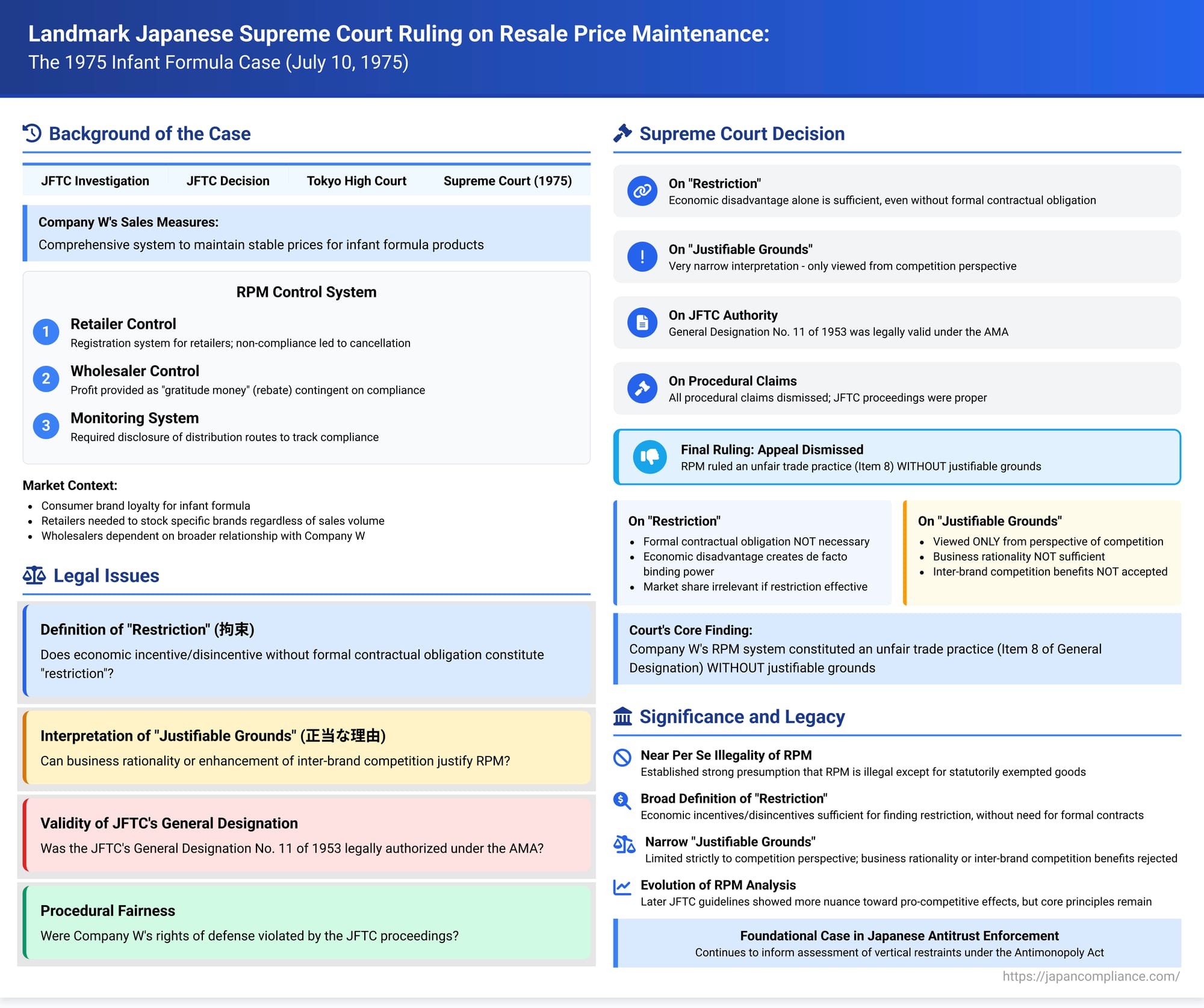

On July 10, 1975, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment concerning resale price maintenance (RPM) practices in the context of infant formula distribution. This case, often referred to as the First Infant Formula Case, involved an appeal against a Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) decision that found a company's sales practices constituted an unfair trade practice under Japan's Act on Prohibition of Private Monopolization and Maintenance of Fair Trade (Antimonopoly Act or AMA). The Court's decision provides crucial interpretations of key concepts like "restriction" and "justifiable grounds" within the framework of Japanese competition law, particularly regarding vertical restraints.

Factual Background

The appellant, Company W, served as the general distributor for infant formula products manufactured by another entity, Company S. Seeking to maintain stable prices for two specific infant formula products, "Product A" and "Product N," Company W implemented a comprehensive set of sales policies (hereinafter referred to as the "Sales Measures").

The core objective of these Sales Measures was price stabilization. Company W predetermined the wholesale and retail prices for its products and devised several strategies to ensure compliance by its distributors:

- Retailer Control: Company W established a registration system for retailers. Retailers who failed to adhere to the designated retail price faced the cancellation of their registration. This effectively meant losing the ability to sell Company W's products.

- Wholesaler Control: The control mechanism for wholesalers was more intricate.

- Pricing: Wholesalers were required to pay Company W the exact amount of the designated wholesale price as the payment for the products supplied.

- Margin System: The wholesaler's profit margin was not built into the purchase price. Instead, it was provided later by Company W in the form of a rebate, termed "gratitude money" (感謝金, kansha-kin).

- Enforcement via Rebate: If a wholesaler violated the designated wholesale price or sold products to retailers who were not part of Company W's registration system, Company W would apply disadvantageous treatment in the calculation of this "gratitude money". This created a strong financial incentive for wholesalers to comply with Company W's pricing and distribution channel restrictions.

- Monitoring: To verify compliance, Company W required wholesalers to disclose the distribution routes for individual products, allowing the company to track sales prices and ultimate destinations.

The JFTC investigated these Sales Measures. It concluded that Company W was engaged in RPM and that these actions constituted an unfair trade practice, specifically falling under Item 8 ("Dealing with Restrictive Terms") of the then-applicable General Designation No. 11 of 1953 (which specified types of unfair trade practices based on Article 2(7)(iv) of the AMA, the precursor to the current Article 2(9)(vi)(b)). Consequently, the JFTC issued a decision ordering Company W to cease and desist from these practices. Company W challenged this decision in the Tokyo High Court, which upheld the JFTC's findings. Company W then appealed to the Supreme Court.

Key Legal Issues and the Supreme Court's Analysis

The Supreme Court addressed several key arguments raised by Company W. The most significant aspects of the ruling relate to the interpretation of "restriction" (kōsoku) and "justifiable grounds" (seitō na riyū) under the AMA.

Issue 1: The Meaning and Existence of "Restriction"

Appellant's Argument (Company W): Company W argued that its Sales Measures did not actually "restrict" the transactions between its wholesalers and the retailers they sold to. It particularly emphasized that the JFTC and the High Court had unreasonably failed to consider Company W's relatively low market share in the infant formula market, implying that a company with low market power could not effectively impose such restrictions.

Supreme Court's Analysis: The Court rejected Company W's argument and affirmed the finding that the Sales Measures constituted a restriction.

- Defining "Restriction": The Court clarified the legal standard for a "restriction" in this context. It held that a formal contractual obligation compelling adherence to the terms is not necessary. It is sufficient if non-compliance with the terms realistically entails some form of economic disadvantage for the counterparty (in this case, the wholesaler), thereby ensuring the practical effectiveness of the restriction. This interpretation aligns with established precedent regarding mutual "restraint" in the context of unreasonable restraints of trade (cartels) under AMA Article 2(6). The focus is on the de facto binding power created by the economic consequences of non-compliance. The commentary notes that while this specific case involved clear economic disadvantages (loss of rebates), the requirement of "economic disadvantage" might be interpreted somewhat broadly, focusing more on the overall effectiveness ensured by the supplier's artificial means.

- Applying the Definition to the Facts: The Court then applied this standard to the specific circumstances of the infant formula market and Company W's practices. It highlighted several critical findings from the JFTC decision, which it deemed supported by substantial evidence:

- Product Characteristics: Infant formula possesses unique characteristics. Consumers tend to develop brand loyalty and typically purchase by specifying a particular brand, even if price differences exist between brands. Switching brands after initial use is uncommon.

- Constant Demand: Consequently, there is a persistent demand for specific brands like those sold by Company W.

- Retailer Necessity: Retailers catering to this demand must stock Company W's formula, regardless of the sales volume, to meet consumer requests.

- Wholesaler Position: Wholesalers dealing with Company W often handled not only the infant formula but also numerous other baby products and pharmaceuticals manufactured or sold by Company W. Therefore, even if Company W's formula had a low market share and low sales volume for a particular wholesaler, the wholesaler could not realistically afford to cease its overall business relationship with Company W just to avoid the formula restrictions.

- Economic Compulsion: As long as wholesalers continued the relationship, they were compelled to follow Company W's specified sales prices and customer limitations (selling only to registered retailers) to secure their essential profit margin, which came via the "gratitude money" rebate system. Failure to comply directly impacted their profitability.

- Conclusion on Restriction: Based on this factual context, the Court concluded that the Sales Measures effectively restricted the transactions between wholesalers and retailers concerning price and sales counterparts. This restriction was real and effective irrespective of Company W's overall market share in the infant formula sector. The specific market dynamics and the structure of the rebate system created sufficient leverage for Company W to enforce its terms. Therefore, the JFTC's finding of a "restriction" was deemed reasonable.

Issue 2: The Absence of "Justifiable Grounds"

Appellant's Argument (Company W): Company W contended that even if its actions constituted RPM, there were "justifiable grounds" for them, meaning they should not be deemed illegal under General Designation Item 8. It presented two main arguments:

- Finding no justifiable grounds for RPM contradicts the existence of AMA Article 24-2, which specifically exempts RPM for certain designated commodities and copyrighted works under certain conditions.

- RPM applied to products with weak market competitiveness (like Company W claimed its formula had) could actually promote competition between different brands (inter-brand competition), and this pro-competitive effect should be considered "justifiable grounds."

Supreme Court's Analysis: The Court firmly rejected the existence of justifiable grounds in this case, providing a narrow interpretation of the concept.

- Purpose of Unfair Trade Practice Regulation: The Court began by stating that the fundamental purpose of prohibiting unfair trade practices under the AMA is to maintain a fair competitive order. The term "unjustly" (futō ni) used in the underlying AMA provision (then Art. 2(7)(iv)) must be interpreted in light of this purpose.

- Interpretation of General Designation Item 8: The Court interpreted General Designation Item 8 (which prohibited "Dealing with Restrictive Terms... without justifiable grounds") as reflecting this purpose. The provision identifies the inherent "unjustness" in the fact that restrictive conditions impede competition in the counterparty's business activities. The phrase "without justifiable grounds" was interpreted as an exception clause, intended to exclude specific instances where, despite the restrictive condition, this inherent "unjustness" (i.e., harm to fair competition) is absent.

- Defining "Justifiable Grounds": Crucially, the Court defined "justifiable grounds" as a concept viewed exclusively from the standpoint of maintaining the fair competitive order. It means circumstances where the restrictive condition poses no risk of impeding free competition in the counterparty's business activities. The Court explicitly stated that reasons which might appear "justifiable" in an ordinary sense – such as having business rationality or necessity from a management or transactional perspective unrelated to maintaining the competitive order – cannot constitute "justifiable grounds" under this provision. This established a very high bar for invoking the exception.

- Relationship with RPM Exemptions (Art. 24-2): The Court dismissed the argument regarding Article 24-2. It explained that Article 24-2 operates on the premise that RPM constitutes a restrictive dealing (an unfair trade practice) and is illegal unless justifiable grounds exist (or unless it falls under the exemption). Article 24-2 provides a specific, exceptional exemption for certain designated goods (typically daily necessities designated by the JFTC) and copyrighted works, based on different economic policy considerations – primarily to prevent detrimental effects like brand image erosion caused by extreme discounting or loss-leader sales, even after considering the need to secure competition. For these exempted items only, the legality of RPM is determined without inquiring into the presence or absence of justifiable grounds. This exceptional provision, aimed at different policy goals than the general prohibition in Item 8 (which focuses on ensuring competition among distributors), does not conflict with the principle that RPM for non-exempted goods (like infant formula) should be assessed individually for its anti-competitive effect (i.e., lack of justifiable grounds).

- Inter-Brand Competition Argument: The Court also rejected the argument that potential enhancement of inter-brand competition could serve as a justifiable ground. It reiterated that the primary focus of General Designation Item 8 is to eliminate restrictions on competition in the counterparty's business activities – that is, intra-brand competition (competition among distributors of the same brand). The Court stated that even if RPM by a supplier might strengthen the competitive relationship between that supplier and its own competitors (inter-brand competition), this does not necessarily produce the same positive economic effects for consumers as allowing free price competition among the distributors of the specific product (intra-brand competition). As long as intra-brand competition is restricted, the potential harm to competition cannot be denied simply because inter-brand competition might be enhanced.

- The commentary points out that this ruling became a basis for the long-held view in Japan that RPM is generally treated as per se illegal or nearly so, where the anti-competitive effect is presumed from the conduct itself. It suggests the Court, possibly influenced by the differentiated nature of demand for Company W's formula (meaning consumers specifically sought that brand), was particularly concerned that restricting intra-brand price competition would directly harm these consumers, negating any potential benefits from enhanced inter-brand competition. The commentary also notes that if demand were not so differentiated, and consumers could easily switch brands, the Court's concerns might have been lessened. Furthermore, it mentions that the top two competitors in the market were also engaging in similar RPM practices, suggesting a potential for coordinated behavior that would dampen, rather than enhance, overall competition.

- Conclusion on Justifiable Grounds: Applying this strict interpretation, the Court found no justifiable grounds for Company W's RPM practices. The High Court's judgment upholding the JFTC decision on this point was affirmed. The commentary observes that while this judgment appeared to strongly reject the consideration of pro-competitive justifications, later Supreme Court cases concerning other types of unfair trade practices have acknowledged certain justifications. Moreover, current JFTC guidelines, while maintaining a generally strict stance on RPM, explicitly acknowledge that pro-competitive effects can be considered in the analysis. Therefore, the absolute rejection of justifications in this specific ruling might be read in the context of the specific arguments made and the prevailing legal thought at the time, rather than as a complete bar on considering pro-competitive effects in all RPM cases today.

Issue 3: Validity of the JFTC's General Designation

Appellant's Argument (Company W): Company W challenged the legality of the JFTC's General Designation itself. It argued that the AMA (specifically Art. 2(7) at the time) only empowered the JFTC to issue "Special Designations" – rules targeting specific unfair practices within specific industries – not broad, abstract "General Designations" like No. 11 of 1953, which applied across industries. Alternatively, if the AMA did authorize such general designations, it constituted an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power by the Diet (Japan's parliament) under Article 41 of the Constitution.

Supreme Court's Analysis: The Court rejected this challenge.

- It found that the legislative history and purpose of the AMA revisions clearly indicated that the JFTC's authority was not limited to issuing only Special Designations. The existence of specific procedural requirements for Special Designations (like mandatory public hearings under AMA Art. 71) did not imply a prohibition on other forms of designation.

- Regarding the existing General Designation No. 11, the Court found that it provided more specific and concrete definitions of the types of conduct listed generally in the AMA statute (Art. 2(7)). Given the need for rules applicable across all business fields in a dynamic economy, the level of specificity in the General Designation was deemed sufficient and not contrary to the intent of the legislative delegation.

- The constitutional argument was dismissed because the Court found that the scope of the delegation under AMA Article 2(7) was substantially limited by the statute itself; it was not an unfettered "blank check" delegation of power. Thus, the premise for the unconstitutionality claim was lacking.

Issue 4: Procedural Fairness (Scope of Proceedings & Right of Defense)

Company W raised two procedural objections concerning the fairness of the JFTC proceedings.

- Scope of the Cease-and-Desist Order:

- Argument: The initial JFTC proceedings focused on the Sales Measures as applied to "Product A" and "Product N." However, the final JFTC decision ordered Company W to cease the practices with respect to all infant formula it sold. Company W argued this exceeded the scope of the original complaint and violated its right to defend itself adequately.

- Court's Finding: The Court disagreed. Examining the JFTC's initial hearing decision and the course of the proceedings, the Court determined that the actual subject matter under review was the entire sales policy for infant formula decided by Company W at specific management meetings in June and July 1964. The mention of Product A and Product N in the initial documents was merely illustrative, reflecting the products being marketed at that time, and did not limit the scope of the investigation to only those two products. Therefore, ordering the cessation of the policy for all infant formula was not outside the scope of the proceedings. The Court also found no evidence that Company W had been deprived of the opportunity to defend itself regarding the broader application of the policy.

- Inclusion of the "Gratitude Money" System:

- Argument: The initial JFTC hearing decision notice did not explicitly mention the "gratitude money" (rebate) system as a component of the alleged violation. Yet, the JFTC's final decision relied heavily on this system to establish the restrictive nature of the Sales Measures. Company W claimed this also violated its right of defense.

- Court's Finding: The Court acknowledged the omission in the initial notice but ruled it did not constitute a violation. It reasoned that JFTC administrative adjudication procedures, aimed at restoring competitive order, are distinct from civil or criminal litigation and do not require the same strict adherence to initial pleadings. While the JFTC process incorporates adversarial elements to ensure fairness and protect the respondent's right of defense, the scope of findings in the final decision is not rigidly confined to the facts explicitly stated in the initial notice. As long as the "identity of the facts" is maintained (i.e., the core conduct under review remains the same) and the respondent has not been denied a fair opportunity to defend itself throughout the entire course of the proceedings, incorporating related details not mentioned initially is permissible. In this case, the "gratitude money" system was an integral part of the specific Sales Measures being investigated. It was natural for the JFTC's inquiry into whether these measures constituted an unfair trade practice to extend to the details of the rebate system. Its inclusion did not alter the fundamental identity of the conduct under review. Furthermore, the Court found, based on the record, that Company W had been given ample opportunity during the JFTC proceedings to present arguments and evidence regarding the gratitude money system. Therefore, the JFTC's reliance on it in the final decision was deemed lawful.

Issue 5: Other Procedural Issues (Evidence)

Company W also appealed rulings related to evidence, including the JFTC's denial of its requests to compel the submission of certain documents and allow inspection of records from another case, as well as the High Court's refusal to admit new evidence during the judicial review phase. The Supreme Court dismissed these arguments, finding the lower bodies' actions consistent with the relevant procedural provisions of the AMA concerning the necessity of evidence, the definition of "interested party" entitled to inspect records, the "substantial evidence rule" (whereby JFTC findings of fact are binding on courts if supported by substantial evidence), and the strict limitations on introducing new evidence during judicial review of JFTC decisions.

Conclusion and Significance

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed Company W's appeal, upholding the JFTC's decision finding the RPM practices illegal. This 1975 judgment remains a cornerstone decision in Japanese competition law regarding resale price maintenance. Its key contributions include:

- Defining "Restriction": Establishing that practical effectiveness, often achieved through economic disadvantage for non-compliance, is sufficient to constitute a "restriction," even without explicit contractual obligations.

- Narrowly Interpreting "Justifiable Grounds": Holding that justifiable grounds for restrictive conduct exist only when there is no risk of impeding free competition from the perspective of maintaining the competitive order, largely excluding broader business justifications.

- Setting a Precedent for RPM: Reinforcing the view that RPM for goods not specifically exempted under Article 24-2 is generally considered an unfair trade practice under the AMA, with limited scope for justification. While subsequent developments and guidelines have introduced more nuance, particularly regarding the potential consideration of pro-competitive effects, this case established a foundational principle of skepticism towards RPM in Japanese antitrust enforcement.

The Court's detailed analysis, particularly concerning the interplay between market characteristics, supplier leverage, and the effectiveness of restrictive terms, continues to inform the assessment of vertical restraints under the Antimonopoly Act.