Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Purchaser's Rights in Property Auctions Involving Non-Existent Land Lease Rights

Case Name: Case Seeking Return of Purchase Price, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 5 (O) No. 1054

Date of Judgment: January 26, 1996

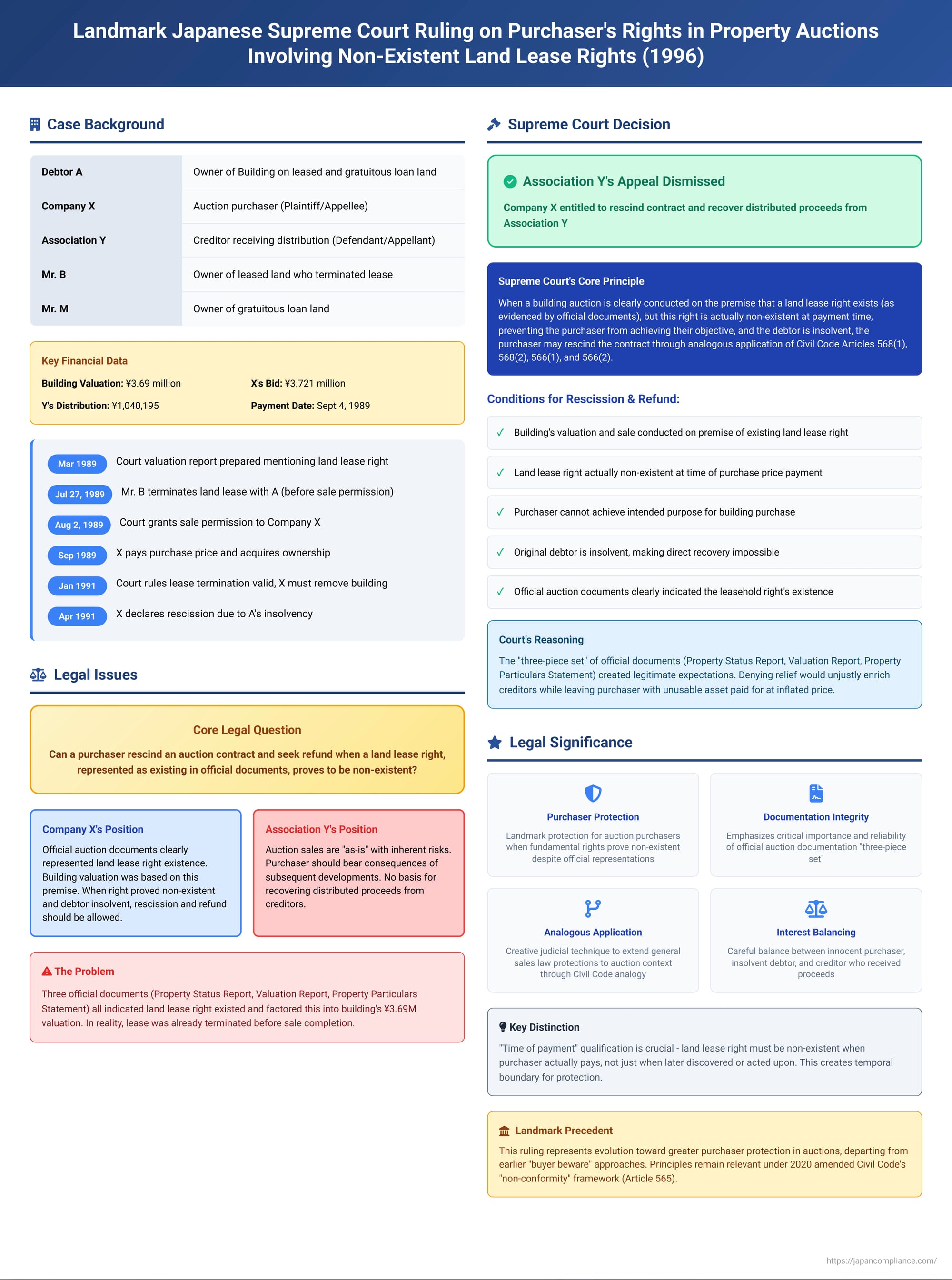

This article delves into a significant January 26, 1996, judgment by the Supreme Court of Japan. The case addresses the remedies available to a purchaser in a compulsory auction of a building when a land lease right, which was presumed to exist and formed the basis of the building's valuation and sale, was in fact non-existent at the time of purchase. This ruling has important implications for understanding purchaser protection in Japanese real estate auctions.

Facts of the Case

The factual background leading to this Supreme Court decision is as follows:

Mr. A, a debtor, owned a building ("the Building") situated on two parcels of land. One parcel ("the Leased Land") was leased by Mr. A from its owner, Mr. B, under a formal lease agreement ("the Land Lease Agreement"), granting Mr. A a land lease right (shakuchiken). The adjacent parcel ("the Gratuitous Loan Land") was used by Mr. A based on a gratuitous loan agreement with its owner, Mr. M.

Due to Mr. A's debts, compulsory auction (kyōsei keibai) proceedings were initiated against the Building. In the course of these proceedings, several official documents were prepared and made available to potential bidders:

- Valuation Report (hyōkasho): Dated March 31, 1989, prepared by a court-appointed appraiser. This report stated that the Building was constructed on the Leased Land (subject to the land lease right) and the Gratuitous Loan Land. It explicitly mentioned that the Building's appraised value of JPY 3.69 million was calculated by taking into account the existence of the land lease right (of indeterminate duration) for the Leased Land and the right of use for the Gratuitous Loan Land.

- Property Status Report (genkyō chōsa hōkokusho): Dated April 13, 1989, prepared by a court execution officer (shikkōkan). This report indicated that the purchaser of the Building would naturally succeed to the land lease right associated with the Leased Land.

- Property Particulars Statement (bukken meisai sho): Prepared by the execution court. This document also noted the existence of the Land Lease Agreement (of indeterminate duration) for the Leased Land for the benefit of the Building.

Company X, the eventual purchaser (and appellee in the Supreme Court), reviewed these three key documents on July 17, 1989. Additionally, Mr. M (owner of the Gratuitous Loan Land) had expressed an intention to Company X to lease the Gratuitous Loan Land to them anew. Based on this information, Company X believed it would secure the necessary land use rights for the entire property upon purchasing the Building.

Consequently, Company X submitted a bid of JPY 3,721,000, exceeding the minimum bid price of JPY 3.69 million (which was based on the official valuation). The court granted a sale permission decision to Company X on August 2, 1989. Company X paid the purchase price on September 4, 1989, acquired ownership of the Building, and completed the ownership transfer registration on September 13, 1989.

From the proceeds of this sale, Association Y, a creditor of Mr. A (and the appellant in the Supreme Court), received a distribution of JPY 1,040,195 on October 6, 1989.

However, a critical issue unbeknownst to Company X at the time of bidding and payment emerged. Mr. B, the owner of the Leased Land, had already sent a notice to Mr. A on July 27, 1989 – prior to the court's sale permission decision to Company X – terminating the Land Lease Agreement due to Mr. A's failure to pay rent.

Subsequently, on January 8, 1990, Mr. B filed a lawsuit against Company X, demanding the removal of the Building from the Leased Land and the return of the land. The Osaka District Court, on January 29, 1991, ruled in favor of Mr. B, finding that the termination of the Land Lease Agreement was valid. This judgment effectively meant Company X could not use the Leased Land for the Building.

Facing the loss of the essential land lease right, Company X found that the purpose for which it purchased the Building was unattainable. On April 22, 1991, Company X notified Mr. A (the debtor) of its intention to rescind the sale contract for the Building formed through the compulsory auction. At this time, Mr. A was insolvent.

Company X then initiated legal proceedings against Association Y (the creditor who had received a distribution from the sale proceeds) to recover the distributed amount.

Procedural History

The Osaka District Court, as the court of first instance, found in favor of Company X. It affirmed the purchaser's right to rescind the contract by analogous application of relevant Civil Code provisions and ordered Association Y to return the distributed sales proceeds.

Association Y appealed to the Osaka High Court. The High Court also affirmed the analogous application of the Civil Code and upheld Company X's claim for rescission and refund. However, it modified the first instance judgment by ordering Association Y to return the funds in exchange for Company X completing the procedures to cancel the registration of its ownership of the Building (a condition of simultaneous performance).

Association Y further appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, on January 26, 1996, dismissed Association Y's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions in substance regarding Company X's right to rescind and seek a refund.

The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning revolved around the analogous application (ruisui tekiyō) of Articles 568(1), 568(2), 566(1), and 566(2) of the pre-amendment Civil Code to the facts of this case. These articles primarily deal with a seller's liability (often termed warranty liability or liability for defects) when the subject matter of a sale is deficient in terms of rights that were presumed to exist or when it is encumbered by rights of third parties.

The Court established a general principle:

- If, in a compulsory auction of a building, it is clear that the building's valuation and minimum sale price were determined on the premise that a land lease right exists for the building's benefit, and the sale was conducted on this basis;

- AND, in reality, this land lease right did not exist at the time the purchaser paid the purchase price;

- AND, as a result, the purchaser cannot achieve the purpose for which they bought the building;

- AND, the debtor is insolvent;

- THEN, it is appropriate to allow the purchaser, by analogous application of the aforementioned Civil Code articles, to rescind the sale contract arising from the compulsory auction and demand the return of the purchase price from creditors who received distributions from those proceeds.

The Supreme Court provided a detailed rationale for this principle:

- Expectation of Acquiring Leasehold Rights: When a land lease right exists for a building, a purchaser of that building typically expects to acquire this leasehold right as an ancillary right. The legal framework for compulsory auctions supports this expectation.

- Duties of Auction Officials and Transparency:

- The court execution officer (shikkōkan) is obligated to investigate the debtor's basis for occupying the land, including the existence and details of any land use rights, and to record these findings in the Property Status Report.

- The court-appointed appraiser (hyōka-nin), in valuing the building, must consider not only the value of the structure itself but also the value of any associated land lease right, detailing this calculation process in the Valuation Report.

- The execution court determines the minimum sale price based on this comprehensive valuation and prepares a Property Particulars Statement. These documents (Property Status Report, Valuation Report, and Property Particulars Statement – often referred to as the "three-piece set" or san-ten setto) are made available for public inspection.

- Premise of the Sale: When these official documents clearly indicate the existence of a land lease right, and this forms the basis for the building's valuation and minimum sale price, the auction is unequivocally conducted on the premise that the purchaser will acquire this leasehold right.

- Equity and Fairness: If, despite this clear premise, the land lease right is non-existent at the time of payment, preventing the purchaser from achieving their objective, and the debtor is insolvent (making recovery from the debtor impossible), allowing rescission and recovery from creditors who benefited from the sale proceeds aligns with principles of fairness among the three parties involved: the purchaser, the debtor, and the creditors. To deny such a remedy would unjustly enrich the creditors and leave the purchaser with an unusable asset for which they paid a price reflecting the non-existent right.

Applying this principle to the specific facts of the case, the Supreme Court found:

- The auction of the Building was clearly conducted on the premise that the land lease right on the Leased Land existed, as evidenced by the Valuation Report, Property Status Report, and Property Particulars Statement.

- The land lease right was, in fact, non-existent when Company X paid the purchase price because Mr. B had validly terminated the Land Lease Agreement with Mr. A prior to the sale's finalization.

- Company X was unable to achieve its purpose for purchasing the Building (i.e., using it on the Leased Land).

- Mr. A, the debtor, was insolvent at the time Company X declared rescission.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Company X was entitled to rescind the auction sale contract and claim a refund of the distributed sale proceeds from Association Y, based on the analogous application of Civil Code Articles 568(1), 568(2), 566(1), and 566(2). The High Court's judgment was deemed just and affirmed.

The Supreme Court also briefly addressed other points of appeal raised by Association Y:

- One-Year Exclusion Period: Association Y argued that Company X's claim was time-barred under Article 566(3) of the Civil Code (which typically requires claims for defects in rights to be made within one year of the buyer discovering the defect). The Supreme Court upheld the High Court's finding that Company X had exercised its right to rescind within one year of learning about the valid termination of the Land Lease Agreement.

- Factual Findings: The Supreme Court dismissed other arguments by Association Y that challenged the lower court's factual determinations, stating that these findings were reasonably supported by the evidence and that the appellant's arguments were merely re-assertions of their own views or criticisms of the lower court's exclusive domain of fact-finding.

Analysis and Significance

This 1996 Supreme Court decision is pivotal for several reasons, particularly concerning the protection of purchasers in real estate auctions under Japanese law:

- Clarification of Purchaser Remedies for Non-Existent Rights: The judgment provides crucial clarification on the remedies available to a purchaser when an essential right, such as a land lease right, which was represented as existing and formed a fundamental basis for the auction, turns out to be absent. Prior to this, the legal position could be less certain, as compulsory auctions inherently carry different risk profiles than ordinary negotiated sales.

- Addressing a Legislative Gap through Analogous Application: The Civil Code, at the time, did not directly and explicitly regulate the precise scenario of a non-existent land lease right in a compulsory building auction. The Supreme Court's use of "analogous application" (ruisui tekiyō) of existing articles governing seller's liability in general sales demonstrates a common judicial technique in civil law jurisdictions to bridge legislative gaps and achieve equitable outcomes. By applying Articles 568 (concerning rights belonging to the subject-matter of a sale that do not exist) and 566 (concerning encumbrances or the non-existence of stated servitudes), the Court extended the principles of fairness and protection found in ordinary sales to the context of compulsory auctions, with necessary modifications (such as the debtor's insolvency as a precondition for claiming from creditors).

- Emphasis on the Integrity of Auction Documentation: The ruling underscores the critical importance and reliability of the official documents prepared for compulsory auctions – the Property Status Report, Valuation Report, and Property Particulars Statement. The Supreme Court's reasoning heavily relied on the fact that these documents explicitly stated the existence of the land lease right and that this information was used to determine the building's value and the minimum bid price. This places a significant responsibility on the execution court, court officers, and appraisers to ensure the accuracy of these documents, as purchasers are entitled to rely on them. The decision implicitly signals that if the auction process itself represents certain rights as part of the sale, the system must provide a remedy if those representations prove false.

- Evolution of Judicial Precedent: The ruling can be seen as part of an evolution in Japanese case law towards greater purchaser protection in auctions. Earlier precedents, including some from the pre-war Great Court of Cassation (Daishin'in), had sometimes taken a stricter view, suggesting that building auctions did not necessarily guarantee the existence or transfer of land use rights, and that bidders assumed certain risks. This 1996 judgment, particularly in light of the post-war Civil Execution Act (Minji Shikkō Hō) which reformed and systematized execution proceedings with an emphasis on clearer investigations and disclosures, reflects a more protective stance, especially where official documentation forms a clear basis for the purchaser's expectations.

- Balancing Interests: The decision carefully balances the interests of the innocent purchaser (Company X), the insolvent debtor (Mr. A), and the creditor who received proceeds (Association Y). By allowing rescission and recovery from the creditor only when the debtor is insolvent and the purchaser cannot achieve their primary objective, the Court fashions a remedy that aims for fairness. The creditor, in this specific scenario, is essentially asked to return funds they might not have received had the true state of the land lease right been known and reflected in a (presumably lower or non-existent) sale price.

- The "Time of Payment" Qualification: A notable aspect of the judgment is its specification that the land lease right was non-existent "at the time the purchaser paid the purchase price." This leaves open questions about scenarios where a land lease right might exist at the moment of payment but is subsequently lost due to a cause that pre-dated the payment (e.g., a pre-existing ground for termination that is acted upon later). The specific facts of this case, where the termination notice was issued before the sale permission and payment, made the application of this principle relatively straightforward. Future cases might need to explore the boundaries of this temporal qualification.

- Relevance under the Amended Civil Code: While this judgment was rendered under the pre-2020 amendment Civil Code, its underlying principles regarding purchaser expectations and the consequences of misrepresentations in auction particulars remain relevant. Under the amended Civil Code, which reconceptualized seller's liability in terms of "non-conformity of the subject matter with the terms of the contract" (契約不適合責任 - keiyaku futekigō sekinin), a similar situation would likely be analyzed under Article 565. If the existence of the land lease right was deemed to be a part of the "content of the contract" formed by the auction, its absence would constitute a non-conformity. The determination of what constitutes the "content of the contract" in an auction would still heavily rely on the official auction documents (the "three-piece set"), suggesting that a comparable outcome might be reached.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in the Heisei 5 (O) No. 1054 case represents a significant affirmation of purchaser rights in Japanese compulsory auctions. By allowing the analogous application of Civil Code provisions on seller's liability, the Court provided a pathway for relief when a purchaser is misled by official auction documentation regarding the existence of essential rights like a land lease. The judgment emphasizes the importance of accurate information in the auction process and seeks to ensure a fair outcome when the fundamental purpose of a purchase is frustrated due to the non-existence of such critical, represented rights, particularly when the original debtor is insolvent. This case continues to serve as an important precedent illustrating the judiciary's role in adapting existing legal principles to ensure equity in specific transactional contexts.