Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Employment Income Taxation and Equality

Judgment Date: March 27, 1985

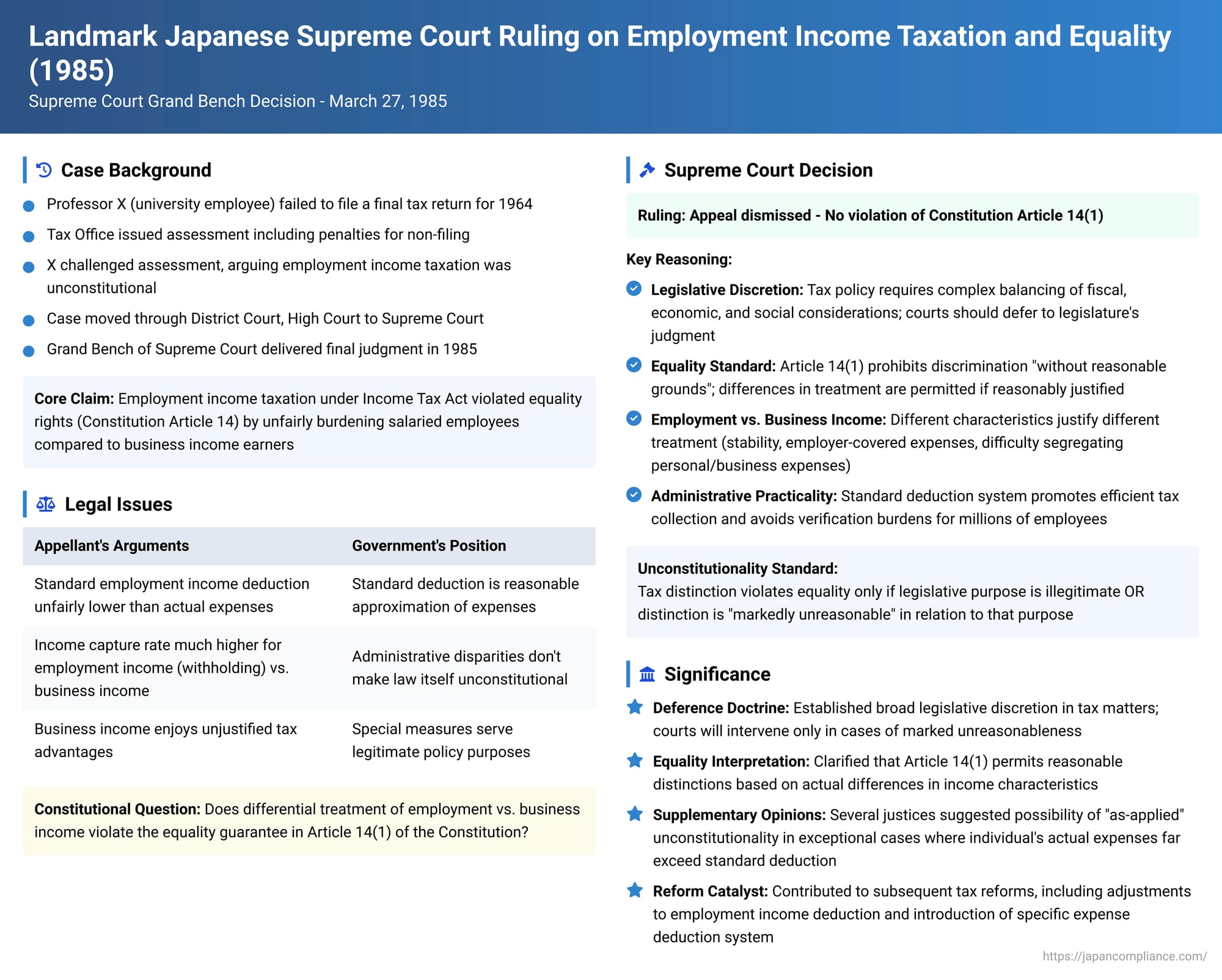

In a significant decision with lasting implications for Japanese tax law and constitutional interpretation, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered its judgment in a case challenging the fairness of employment income taxation compared to business income taxation. The case, formally an appeal seeking the cancellation of an income tax assessment, explored deep questions about equality under the law, legislative discretion in tax matters, and the practicalities of tax administration. The appeal was ultimately dismissed, with the Court upholding the constitutionality of the then-existing tax provisions.

Background of the Dispute

The appellant, referred to as X (originally Mr. M.O., whose suit was continued by his successor Ms. N.O. after his passing), was a professor at D University. For the 1964 tax year, X had employment income and some miscellaneous income. Under the provisions of the Former Income Tax Act (specifically, the version predating the 1965 amendments), individuals with employment income exceeding a certain threshold were required to file a final tax return. X failed to do so.

Consequently, Y, the Head of the Sakyo Tax Office, issued a tax determination for X. This included an assessment of his total income, taxable income, tax due, and an additional amount for failure to file. X contested these determinations, launching a legal battle that would span two decades and culminate in this Supreme Court ruling.

X's core contention was that the taxation of employment income under the Former Income Tax Act was unconstitutional, violating Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution of Japan, which guarantees equality under the law. He argued that salaried employees were subjected to unfairly heavy taxation and discriminatory treatment compared to other categories of income earners, particularly those with business income.

The Plaintiff's Core Arguments for Unconstitutionality

X's challenge was built on three main pillars:

- Inequitable Treatment of Necessary Expenses: The Former Income Tax Act allowed individuals earning business income to deduct the actual necessary expenses incurred in generating that income. In contrast, employment income earners were not permitted to deduct actual expenses. Instead, they were granted a standard "employment income deduction." X argued that this standard deduction was often considerably less than the actual expenses incurred by employees in the course of their work, leading to an unfair inflation of their taxable income. He asserted that his own actual expenses exceeded this standard deduction.

- Disparity in Income Capture Rates: X pointed to a significant and persistent difference in "income capture rates" between employment income and other types of income, especially business income subject to self-assessment. Employment income is typically subject to withholding tax at the source, leading to a very high rate of capture by tax authorities. Business income, relying on self-declaration, historically had a lower capture rate. X argued this systemic discrepancy resulted in an unjust shifting of the tax burden onto salaried employees.

- Unjustified Tax Advantages for Business Income: X contended that various special tax measures and benefits available to business income earners lacked reasonable justification. These preferential treatments, he argued, further exacerbated the disparity, compelling salaried workers to bear an excessively heavy tax burden in comparison.

The case proceeded through lower courts. The Kyoto District Court initially dismissed X's claims. On appeal, the Osaka High Court, while introducing the concept of "appropriate professional expenses" and suggesting that employees could theoretically seek non-taxation for actual expenses exceeding the standard deduction, ultimately did not find in X's favor regarding his specific circumstances and dismissed his appeal. X then brought the case to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment and Reasoning

The Supreme Court meticulously addressed each of X's arguments, ultimately concluding that the challenged provisions of the Former Income Tax Act regarding employment income did not violate Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution.

1. The Distinction in Deducting Necessary Expenses

The Court first acknowledged the differential treatment: business income allowed for the deduction of actual necessary expenses, while employment income was subject to a standard employment income deduction. The Court recognized that this standard deduction was intended, at least in part, to account for necessary expenses in an estimated manner.

(a) The Constitutional Guarantee of Equality (Article 14, Paragraph 1)

The Court reiterated that Article 14, Paragraph 1, which states that "all of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin," is a cornerstone of the Constitution. This guarantee extends to all governmental actions, including the exercise of taxing power.

However, the Court clarified that this principle does not mandate absolute or mechanical equality, treating all individuals uniformly regardless of their factual differences. Such an approach, the Court noted, could paradoxically lead to substantive inequality. Instead, Article 14, Paragraph 1 prohibits discrimination without reasonable grounds. Therefore, legislative distinctions in legal treatment that correspond to actual differences among individuals are permissible, provided such distinctions are reasonable.

(b) Legislative Discretion in Tax Law

The Court then delved into the nature of tax legislation. Taxes, it explained, are financial contributions levied by the state based on its taxing power, not as a direct payment for specific services, but to fund public expenditures. In a democratic nation, the expenses necessary for the state's maintenance and activities should be borne by the citizens, the sovereigns, as a common cost, determined through their representatives. The Japanese Constitution embodies this view, stipulating that citizens have the duty to pay taxes as provided by law (Article 30) and that new taxes or modifications to existing ones require law or conditions prescribed by law (Article 84).

Consequently, tax requirements and the procedures for assessment and collection must be clearly defined by law. The Constitution itself does not specify the detailed content of these tax laws, delegating this to the legislature. The Court emphasized that modern taxation serves multiple functions beyond merely satisfying fiscal needs; it plays roles in income redistribution, optimal resource allocation, and economic stabilization. Determining tax burdens thus necessitates comprehensive policy judgments encompassing fiscal, economic, and social policy considerations, as well as highly specialized, technical assessments for defining taxable events and amounts.

Given these complexities, the formulation of tax laws is primarily entrusted to the policy-oriented and technical judgment of the legislature, which is expected to act based on accurate data concerning national finances, the socio-economic landscape, national income, and citizens' living standards. As such, the judiciary must, in principle, respect the discretionary judgment of the legislature in this domain.

Applying this to distinctions in tax treatment based on factors like the nature of income, the Court established a standard for judicial review: such a distinction would contravene Article 14, Paragraph 1 only if its legislative purpose is illegitimate, or if the specific manner of distinction adopted by the legislature is markedly unreasonable in relation to that legitimate purpose. The burden is on the challenger to demonstrate such marked unreasonableness.

(c) Justifications for the Different Treatment of Employment Income Expenses

The Court then examined the rationale behind the differentiated treatment of expense deductions for salaried employees compared to business income earners.

- Nature of Employment: Salaried employees, unlike business proprietors, do not conduct their work based on their own calculations and at their own risk. They provide services under the direction of their employer, and their remuneration is typically predetermined and stable.

- Employer-Covered Costs: It is customary for employers to bear the costs of facilities, equipment, supplies, and other items necessary for the performance of work in the workplace.

- Difficulty in Segregating Expenses: When employees do incur work-related expenses out-of-pocket, these expenditures often reflect personal choices or circumstances. Their connection to income generation can be indirect or unclear, making it generally difficult to draw a clear line between necessary work expenses and personal or household-related expenses.

- Administrative Impracticality: The sheer number of salaried employees is vast. Individually assessing and verifying actual necessary expenses based on each employee's declaration would present substantial technical and quantitative challenges for tax authorities. This could lead to a significant increase in tax collection costs and potentially cause considerable administrative disruption.

- Risk of Inequity: Permitting actual expense deductions for all employees could, paradoxically, lead to unfairness in tax burdens. This could arise from variations in individuals' subjective spending habits or their differing abilities and diligence in documenting and substantiating claimed expenses.

The Court found that the Former Income Tax Act's approach—denying actual expense deductions for employment income and instead providing a standard deduction—was intended to prevent these issues while aiming for a balance in tax burdens between employees and business income earners. The objectives of ensuring a fair distribution of the tax burden and achieving reliable, accurate, and efficient tax collection are fundamental principles of tax law and are, therefore, legitimate legislative purposes.

(d) Reasonableness of the Standard Employment Income Deduction System

The crucial question then became whether the system of providing a standard employment income deduction, and specifically its amount, was reasonable in relation to these legitimate purposes, particularly when compared to the treatment of actual necessary expenses for employment income.

The Court acknowledged that, according to materials like reports from the Tax System Council and legislative history, the employment income deduction was understood to encompass not only an approximation of necessary work-related expenses but also elements intended to adjust for:

i. The perceived lower tax-bearing capacity of employment income (which typically ceases upon the earner's death or incapacitation) compared to income from assets or business.

ii. The fact that employment income is more accurately captured through the withholding tax system compared to other income types.

iii. An adjustment for the interest cost associated with the earlier payment of income tax by employees (on average, about five months sooner) compared to those filing final returns.

However, the Supreme Court stated that such adjustments, while potentially part of legislative policy considerations, are not inherently mandated by the nature of income tax or by Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution. For the purpose of assessing equality in comparison to business income (which allows actual expense deductions), the Court held that the employment income deduction should be evaluated primarily as a proxy for the deduction of necessary expenses related to employment.

Viewing it through this lens, the Court considered that:

- Employers generally cover the costs of major work-related facilities and equipment.

- Many cash allowances provided to employees for specific work-related needs (e.g., travel expenses, commuting costs) and certain benefits-in-kind are often treated as non-taxable income.

Taking these factors into account, the Court concluded that, based on all the evidence presented in the litigation, it was difficult to establish that the amount of actual necessary expenses personally borne by salaried employees generally and clearly exceeded the amount of the standard employment income deduction provided under the Former Income Tax Act. Consequently, the Court could not find that the standard deduction amount was clearly lacking in reasonableness when compared to the likely necessary expenses of employees.

(e) Conclusion on Expense Deductions

Based on this detailed analysis, the Supreme Court ruled that the distinction made by the Former Income Tax Act regarding the deduction of necessary expenses between business income earners and employment income earners was reasonable and did not violate the equality guarantee of Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution.

2. Disparity in Income Capture Rates

X had argued that the significantly lower income capture rate for business income compared to the high capture rate for employment income (due to withholding) rendered the tax system unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court acknowledged that evidence might suggest that the capture rate for business income had indeed been lower than that for employment income for a substantial period. It agreed that, from the standpoint of tax fairness, efforts to rectify such imbalances are necessary.

However, the Court viewed the problem of uneven income capture as being, in principle, an issue to be addressed through the proper and diligent execution of tax administration. Disparities in capture rates alone do not automatically render the underlying tax legislation unconstitutional. Such a conclusion might be warranted only if the disparity were so extreme as to offend fundamental notions of justice and equity, and if it were proven to be a long-standing, constant feature directly attributable to flaws inherent in the tax legislation itself. The Court found that the evidence in this case did not support a finding of such systemic, legislatively embedded unconstitutionality.

Therefore, the Court held that the existence of differing income capture rates did not cause the taxation provisions for employment income to violate Article 14, Paragraph 1.

3. Unjustified Tax Advantages for Business Income

X's third argument was that certain tax incentive measures favoring business income earners were unreasonable and contributed to an unfair burden on salaried employees.

The Supreme Court addressed this point concisely. It stated that even if, hypothetically, some of the tax incentive measures X referred to were found to lack rational justification, such a finding would primarily affect the validity of those specific incentive measures themselves. It would not, the Court reasoned, cascade to render the entirely separate provisions governing the taxation of employment income (which were the subject of X's challenge to his own assessment) unconstitutional or invalid.

The Supreme Court's Final Decision

Having rejected all of X's arguments for unconstitutionality, the Supreme Court concluded that the challenged provisions of the Former Income Tax Act concerning employment income did not violate Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution. Accordingly, the Court upheld the judgment of the Osaka High Court and dismissed X's appeal. The costs of the appeal were to be borne by the appellants.

Supplementary Opinions by Justices

It is noteworthy that several justices of the Grand Bench issued supplementary opinions, adding further nuance and perspective to the Court's decision, even while concurring with the overall judgment.

One significant line of reasoning in these supplementary opinions, supported by multiple justices, was that while the tax law itself (the Former Income Tax Act's provisions) might be constitutional on its face, its application in a specific, concrete case could potentially raise constitutional issues under Article 14, Paragraph 1. This could occur if a particular salaried employee could demonstrate that their actual, necessary work-related expenses clearly and substantially exceeded the standard employment income deduction allowed. In such an exceptional circumstance, applying the standard deduction and thereby taxing income that was, in effect, offset by demonstrable expenses, might be considered markedly unreasonable and thus unconstitutional in its application to that individual. However, these justices also generally agreed that in X's specific case, the evidence did not establish that his expenses clearly and substantially exceeded the deduction.

Another supplementary opinion highlighted the widespread public perception of unfairness in the tax system, particularly among salaried employees, even if the legal provisions themselves withstood constitutional challenge. This opinion referred to statistical data suggesting disparities in the ratios of taxpayers to income earners, and taxable income to total income, across different income categories (salaried workers, agricultural income earners, other business income earners). It posited that a significant portion of these disparities could be attributed to differences in income capture mechanisms (withholding versus self-assessment) and various tax incentive measures. This justice emphasized that the constitutional principle of fair taxation prohibits not only unfavorable treatment of specific groups without reasonable cause but also the granting of special benefits to others without such cause. If income underreporting by business income earners or irrational tax incentives create a substantial and persistent gap in the actual tax burdens, such a situation could indeed raise constitutional questions under Article 14, Paragraph 1. This opinion called for prompt and proactive efforts to rectify such imbalances.

A further perspective offered in a supplementary opinion suggested that even if the excess of actual expenses over the standard deduction is not deemed "substantial," the very existence of such an excess means that, to that extent, tax is being levied where no net income exists. While this might not immediately render the taxation unconstitutional under Article 14, it could be seen as conflicting with the fundamental principle of income taxation, which is to tax net income (income minus necessary expenses). This justice raised the possibility of exploring a system where salaried employees could have the option to choose between the standard deduction and an itemized deduction of actual expenses, warranting broader consideration for reform of the employment income deduction system.

Conclusion and Significance

The 1985 Supreme Court judgment in this case, often referred to as the "Salaryman Tax Lawsuit" or the "Oshima Litigation," remains a landmark decision in Japanese tax jurisprudence. It affirmed the broad legislative discretion granted to the Diet (Japan's parliament) in formulating tax policy, particularly concerning distinctions based on the nature of income and the practicalities of administration. The Court's interpretation of "equality under the law" in the tax context—emphasizing "reasonableness" of distinctions rather than absolute uniformity—has been influential.

While upholding the constitutionality of the standard employment income deduction system, the case and the justices' supplementary opinions also brought to the fore ongoing debates about tax fairness, the challenges of ensuring equitable income capture across different taxpayer groups, and the potential for "as-applied" unconstitutionality in exceptional cases. The issues raised in this litigation contributed to subsequent discussions and reforms in the Japanese tax system, including adjustments to the employment income deduction and the introduction of a system for deducting certain specific expenditures for employees if they exceed a threshold. The case underscores the dynamic interplay between constitutional principles, tax policy, and the evolving socio-economic landscape.