Landlocked Property in Japan: Does a Special Right of Passage Survive Sale of the Access Land?

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of November 20, 1990 (Heisei 2) (Case No. 181 (O) of 1986 (Showa 61))

Subject Matter: Third-Party Objection, Confirmation of Right of Passage, Land Vacation, etc. Claim Case (第三者異議、通行権確認、土地明渡等請求事件 - Daisansha Igi, Tsūkōken Kakunin, Tochi Akewatashi tō Seikyū Jiken)

Introduction

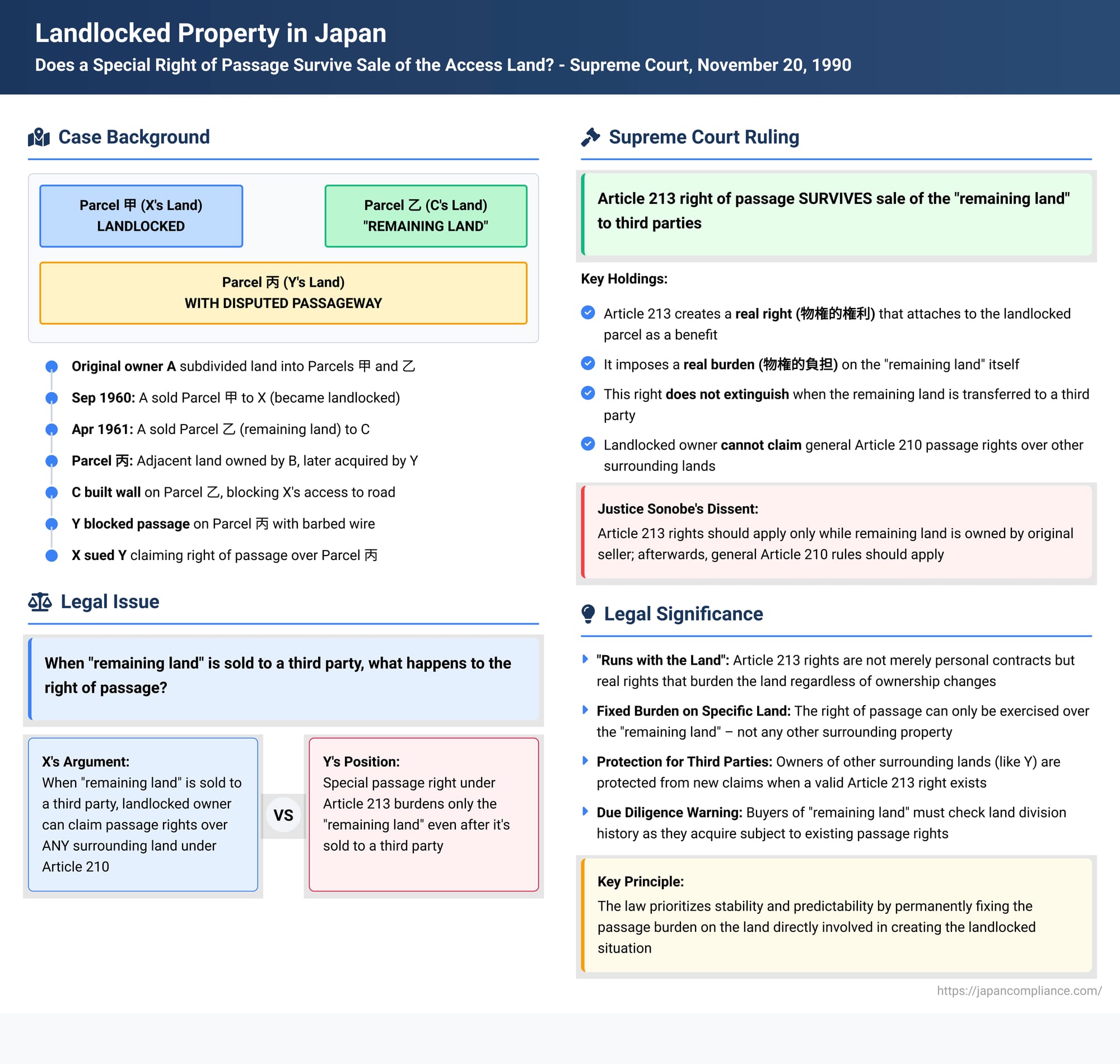

This article analyzes a 1990 Japanese Supreme Court judgment concerning the rights of an owner whose land becomes "landlocked" (袋地 - fukurochi) – meaning it has no direct access to a public road – as a result of a partition or partial sale of a larger tract of land. Japanese Civil Code Article 213 provides a special right of passage for such landlocked parcels, typically over the "remaining land" (残余地 - zan'yochi) from which it was divided, and this right is often without compensation. The central legal question in this case was whether this special right of passage under Article 213 continues to burden the remaining land even if that remaining land is subsequently sold to a third party, or if the landlocked owner must then seek a general right of passage under Article 210 over other surrounding properties.

The dispute involved X (appellant/plaintiff), the owner of a landlocked parcel (Parcel 甲), and Group Y (appellees/defendants), the owners of a different neighboring parcel (Parcel 丙) over which X sought to establish a right of passage.

Factual Background

A originally owned a larger piece of land. In consultation with X, A decided to subdivide and sell this land into Parcel 甲 and Parcel 乙. Before this, A had been using an adjacent parcel, Parcel 丙 (owned by B, and later acquired by Group Y), for vegetable cultivation under a lease. In anticipation of Parcel 甲 becoming landlocked after the sale, A, without B's permission, created a passageway (the "Disputed Passageway") over a portion of Parcel 丙 to provide access from Parcel 甲 to a public road. A and X agreed that X could use this Disputed Passageway over Parcel 丙 free of charge. In September 1960, A completed the subdivision and sold Parcel 甲 to X.

Meanwhile, B (the owner of Parcel 丙) had rescinded the lease to A in August 1960 due to A's unauthorized use of the land (creating the passageway) and successfully sued A for vacation of Parcel 丙. In April 1966, when X started preparations to build on Parcel 甲, Group Y (who had succeeded B as owners of Parcel 丙) blocked X's access over the Disputed Passageway on Parcel 丙 by erecting a barbed-wire fence.

Separately, in April 1961, A sold the other subdivided parcel, Parcel 乙 (the "remaining land" from the original tract after selling Parcel 甲 to X), to C. C built a residence on Parcel 乙 and constructed a stone wall 1-2 meters high along the boundary with X's Parcel 甲, making passage over Parcel 乙 from Parcel 甲 to the public road impossible. As a result, X claimed that the only way to access the public road from Parcel 甲 was via the Disputed Passageway on Group Y's Parcel 丙.

X sued Group Y, asserting, among other things, a right of passage over the Disputed Passageway on Parcel 丙 based on the general provision for landlocked properties, Article 210 of the Civil Code. Both the first instance and appellate courts dismissed X's claim for a right of passage over Group Y's Parcel 丙. They reasoned that when X acquired Parcel 甲 from A, making it landlocked, X obtained a special right of passage under Article 213, paragraph 2, exclusively over the "remaining land," which was Parcel 乙 (then still owned by A, later sold to C). The courts held that this obligation to permit passage under Article 213 is an attribute of the remaining land itself and is inherited by subsequent purchasers of that remaining land (like C). Therefore, X's right of passage was over Parcel 乙 (now C's land), and X could not claim a new right of passage under Article 210 over a different surrounding parcel (Group Y's Parcel 丙). X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that Article 210 should apply to his situation.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of Right of Passage under Article 213: When a parcel of land becomes landlocked as a result of a partition of commonly owned property or a partial transfer of land, the owner of the landlocked parcel, under Article 213 of the Civil Code, acquires a right of passage only over the other land divided from the common property or over the land retained by the seller/transferee from the partial transfer (collectively referred to as "remaining land" - 残余地).

- Right Attaches to the Land (Real Right): The provisions concerning neighborhood relations (相隣関係 - sōrin kankei) in Articles 209 et seq. of the Civil Code are intended to adjust the use of land and are not merely personal (in personam) relationships. The right of passage for landlocked land stipulated in Article 213 is also to be construed as a real right (物権的権利 - bukkenteki kenri) attached to the landlocked parcel and a real burden (物権的負担 - bukkenteki futan) imposed on the remaining land itself.

- Survival Against Subsequent Purchasers of Remaining Land: Therefore, this right of passage under Article 213 over the remaining land does not extinguish even if the remaining land is subsequently transferred to a third party (a specific successor like C in this case).

- No Alternative Right under Article 210: Consequently, the owner of the landlocked parcel cannot claim a general right of passage under Article 210 (which allows passage over any surrounding land under conditions of necessity and compensation) over other surrounding lands not designated as "remaining land" under Article 213.

- To interpret that the Article 213 right extinguishes upon sale of the remaining land would lead to an unreasonable result where the landlocked owner is deprived of legal protection due to an accidental event (the sale of the remaining land) beyond their control.

- Conversely, to allow the landlocked owner to then claim a right of passage over other surrounding lands (like Group Y's Parcel 丙) under Article 210 would impose an unforeseen detriment on the owners of those other lands, which is also not appropriate.

Applying this to the facts, when A sold Parcel 甲 to X, Parcel 甲 became landlocked. X acquired a right of passage under Article 213(2) over Parcel 乙, which was the "remaining land" then still owned by A. Even after A sold Parcel 乙 to C, X's right of passage continued to exist over Parcel 乙 (now C's property). Therefore, X could not assert a general right of passage under Article 210 over Group Y's Parcel 丙. The appellate court's judgment to this effect was deemed correct.

Dissenting Opinion

Justice Sonobe Itsuro dissented. He argued that Article 213 is an exceptional provision to Article 210(1), and considering that the right of passage is determined by both physical attributes of the land and personal elements between owners, Article 213 should be interpreted as granting a right of passage (often gratuitous) over the remaining land only as long as the remaining land is owned by the original party to the division or partial transfer. If the remaining land is subsequently transferred to a third party, the special right under Article 213 should extinguish, and a general right of passage under Article 210 should arise, allowing the landlocked owner to seek access over any surrounding land based on the criteria of necessity and least damage, including potentially the (now third-party owned) remaining land. The dissent argued that the majority's view could lead to unreasonable hardship if the original remaining land becomes unusable for passage after being sold to a third party, and that the purpose of ensuring access for landlocked parcels would be better served by reverting to the general principles of Article 210 in such cases.

Analysis and Implications

This 1990 Supreme Court judgment provides a definitive interpretation of the nature and durability of the special right of passage created under Article 213 of the Civil Code.

- Article 213 Right is a Real Right: The majority opinion firmly establishes that the right of passage over "remaining land" under Article 213 is not merely a personal contractual right between the original parties to the division/sale but is a real right (or a right with real effect) that attaches to the landlocked parcel as a benefit and burdens the remaining land as a servitude.

- Survival Against Subsequent Purchasers: Because it's a real right attached to the land, it "runs with the land." This means that if the remaining land (the servient parcel) is sold to a new owner, that new owner takes the land subject to the pre-existing right of passage held by the owner of the landlocked parcel. The landlocked owner does not lose their specific Article 213 right of passage simply because the servient land changes hands.

- Exclusivity of Passage over Remaining Land: A key consequence is that the landlocked owner's right of passage under Article 213 is exclusive to the designated remaining land. They cannot choose to seek a general right of passage under Article 210 over other neighboring properties if an Article 213 right exists over a specific parcel, even if that parcel is now owned by a third party. The burden is fixed on the original "remaining land."

- Rationale: Predictability and Protection of Other Neighbors: The Court's rationale emphasizes predictability and the protection of other surrounding landowners who were not party to the original act that created the landlocked situation. If the special right over the remaining land could be easily lost and a new right claimed against any neighbor, it would create uncertainty and potential unfairness for those other neighbors.

- Dissent's Concern for Flexibility: The dissenting opinion highlights a potential rigidity in the majority's approach. It argues for more flexibility, suggesting that once the original parties to the land division are no longer involved (i.e., the remaining land is sold), the situation should revert to the general rules of Article 210, allowing for a fresh assessment of the most appropriate and least damaging route, potentially including compensation. The dissent fears that the specific path established under Article 213 might become unsuitable or that the new owner of the remaining land might be unfairly burdened without compensation, especially if the original passage was gratuitous.

- Practical Implications:

- For owners of landlocked parcels created by division/partial sale: Their right of passage is primarily over the specific "remaining land" and continues even if that land is sold.

- For purchasers of "remaining land": They acquire the land subject to this existing statutory right of passage, even if it's not explicitly mentioned in their purchase agreement or registered (as Article 213 rights are statutory and don't always require registration to be effective between the directly affected parcels and their successors). Due diligence would involve checking the history of land divisions.

- For owners of other surrounding lands: They are generally protected from new claims for passage under Article 210 if a valid Article 213 right exists over another specific "remaining land."

This Supreme Court judgment provides a clear rule on the enduring nature of the special right of passage under Article 213, emphasizing its character as a real right burdening the specific "remaining land" irrespective of subsequent transfers of that land. While the dissent raises valid concerns about flexibility and potential hardships, the majority prioritizes the stability and certainty derived from fixing the passage right to the land directly involved in the creation of the landlocked situation.