Land or Cash? Japanese Supreme Court on Inheriting Property Mid-Sale

Date of Judgment: December 5, 1986

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Inheritance Tax Assessment Disposition (昭和56年(行ツ)第89号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

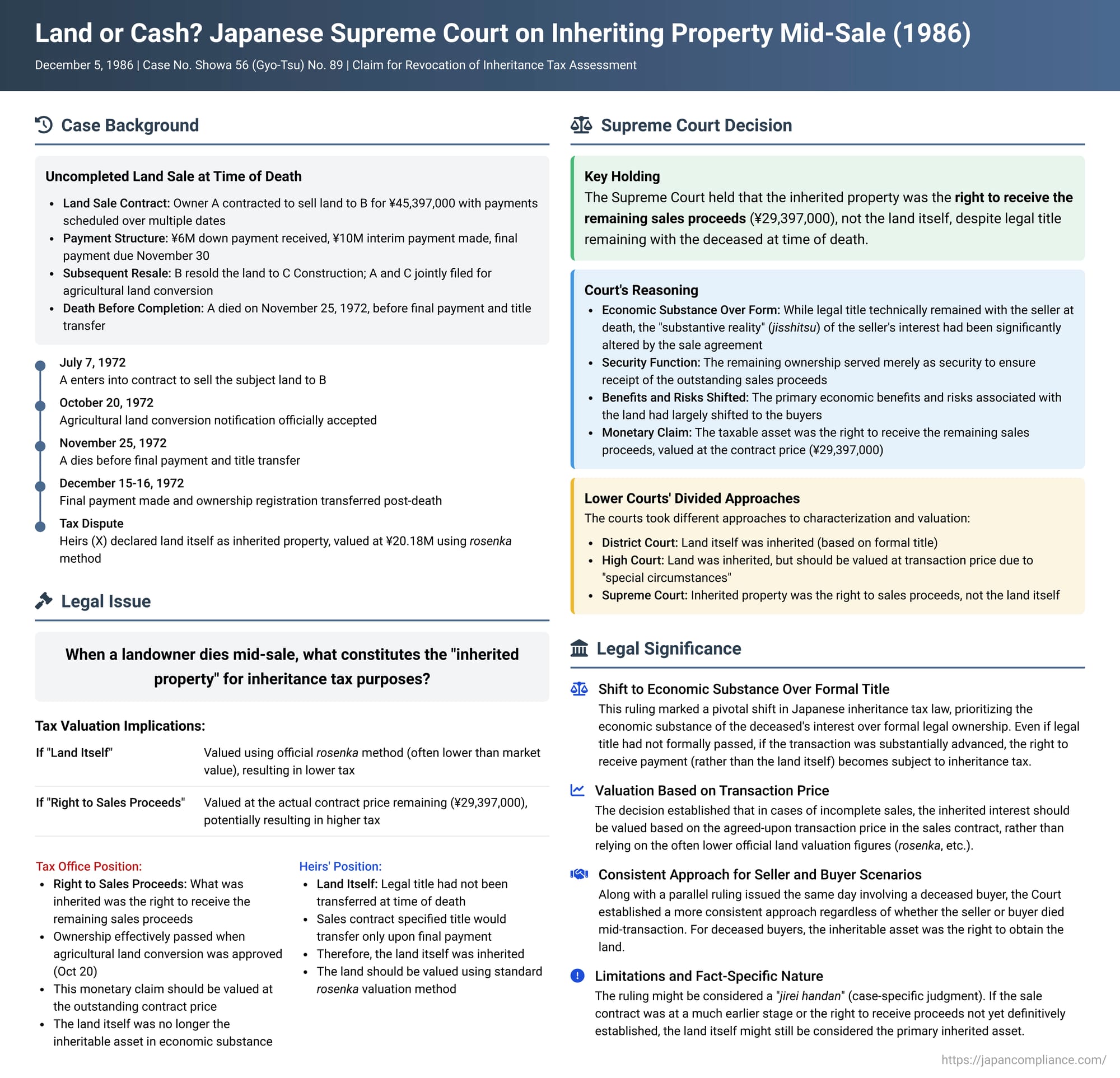

In a significant decision on December 5, 1986, the Supreme Court of Japan provided crucial clarification on what constitutes "inherited property" for the purposes of inheritance tax when a landowner dies after entering into a contract to sell land but before the sale is fully consummated. The ruling marked a notable shift towards emphasizing the economic substance of the deceased's interest at the time of death, rather than strictly adhering to the formalities of legal title transfer. This case underscores the complexities that can arise in valuing inherited assets when transactions are pending.

The Uncompleted Land Sale: A Tax Conundrum for Heirs

The appellants, X et al., were the heirs of an individual, A, who had owned a parcel of land ("the subject land"). The sequence of events leading to the tax dispute was as follows:

- Land Sale Contract: On July 7, 1972, A entered into a contract to sell the subject land to B et al. for a total price of ¥45,397,000. The payment schedule was structured with a down payment of ¥6 million received on the contract date, an interim payment of ¥10 million due on September 30, 1972, and the remaining balance due on November 30, 1972. The agreement stipulated that the transfer of ownership registration and the physical handover of the land would occur concurrently with the final payment. A special clause in the contract permitted the buyers (B et al.) to subdivide the land and resell it to third parties during the contract period.

- Subsequent Resale and Land Use Conversion: After making the interim payment, B et al. resold the subject land to a company, C Construction. The subject land was agricultural land located within an urban promotion area. Conversion of such land to non-agricultural use required notification under the Agricultural Land Act. Both A (the original seller) and C Construction (the subsequent buyer) jointly filed this notification on October 7, 1972, and it was officially accepted on October 20, 1972. Following this, on October 26, 1972, C Construction applied for permits to construct buildings on the land.

- Death of the Seller: A, the original seller, died suddenly on November 25, 1972. This was before the scheduled final payment date of November 30, 1972, and before the title registration had been transferred.

- Post-Death Contract Completion: Due to A's death, the completion of the sale was delayed. The remaining balance of the sales price was eventually paid on December 15, 1972, and the ownership registration was formally transferred on December 16, 1972.

Upon A's death, his heirs, X et al., filed an inheritance tax return. They declared that the "inherited property" subject to tax was the subject land itself, arguing that legal ownership had not yet passed from A at the time of his death. For valuation purposes, they assessed the land at approximately ¥20.18 million. This valuation was based on the official rosenka (roadside land value) method, as prescribed by the then-effective "Basic Circular on Valuation of Inherited Property" (評価通達 - hyōka tsūtatsu), a set of guidelines issued by the National Tax Agency for valuing assets for inheritance and gift tax purposes.

The head of the Y tax office (Nerima Tax Office) disagreed with this assessment. The tax office contended that the ownership of the land should be considered to have effectively passed to C Construction on October 20, 1972, the date the agricultural land use conversion notification was accepted. Based on this view, the tax office asserted that the asset inherited by X et al. was not the land itself, but rather A's right to receive the remaining sales proceeds from the land sale contract (a monetary claim). This monetary claim would be valued at the outstanding contract price. Consequently, the tax office issued a corrective assessment for inheritance tax, along with underpayment penalties.

The first instance court (Tokyo District Court) ruled in favor of the heirs, X et al. It found that the sales contract contained a specific agreement deferring the transfer of legal ownership until the final payment was made. Therefore, at the time of A's death, title had not yet passed, and the land itself was the inheritable asset.

The Tokyo High Court (appellate court) agreed with the District Court that the land itself was the inherited property. However, it diverged on the valuation. The High Court held that in circumstances like this—where the land's market value was concretely evidenced by a recent arm's length transaction price, and the heirs were set to receive (and did shortly receive) the full transaction price—it would be unreasonable to apply the standard official valuation methods (like rosenka) if doing so resulted in a significant disparity with the actual transaction price, especially if that transaction price was objectively fair. The High Court thus concluded that there were "special circumstances" justifying the valuation of the inherited land based on its transaction price. For the purpose of what the heirs substantively inherited, it focused on the remaining sales proceeds of ¥29,397,000 as representing this value (the already paid portions having become part of A's other assets like cash at the time of death). X et al. appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court, challenging primarily the valuation method but implicitly also the characterization of the inherited asset that underpinned that valuation.

The Legal Question: What Exactly is "Inherited Property" in a Pending Sale?

The central legal question before the Supreme Court was: when a landowner dies after executing a contract to sell land, but before the sale is fully consummated (i.e., before final payment is made and legal title is registered), what constitutes the "inherited property" for inheritance tax purposes? Is it:

- The physical land itself, because legal title had not formally passed from the deceased at the moment of death? Or,

- The deceased seller's contractual right to receive the remaining portion of the sales price?

This distinction is critical for inheritance tax calculation because, as highlighted by legal commentary, official valuation methods for land in Japan (such as the rosenka system, which tends to value land at approximately 80% of its posted market price for stability and safety in valuation) often result in assessed values that are considerably lower than actual market transaction prices. If the land itself were deemed the inherited asset and valued using official methods, the resulting inheritance tax could be significantly lower than if the (typically higher) contractual sales proceeds were considered the inherited asset.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Economic Substance Trumps Formal Title

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X et al. While this upheld the monetary outcome determined by the Tokyo High Court (which had used the transaction price for valuation), the Supreme Court did so based on a different legal characterization of the inherited asset.

The Supreme Court reasoned as follows:

- Substantive Nature of the Deceased's Interest: Under the specific factual circumstances of this case, even if legal title to the subject land technically remained with the seller (A) at the time of his death, the "substantive reality" (jisshitsu) of A's interest in the land had been significantly altered by the sale agreement and the subsequent actions (payments, resale by initial buyers, land use conversion approval). The Court found that A's remaining ownership interest, in substance, served merely as a form of security to ensure the receipt of the outstanding sales proceeds. The primary economic benefits and risks associated with the land had largely shifted or were irrevocably committed to the buyers.

- Inherited Property is the Monetary Claim: Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the ownership interest in the land inherited by X et al. did not, in itself, constitute an independent taxable asset for inheritance tax purposes in this context. Instead, the actual taxable asset that passed to the heirs was A's right to receive the remaining sales proceeds (売買残代金債権 - baibai zan-daikin saiken) from the land sale contract, which amounted to ¥29,397,000. The judgment noted that the down payment and interim payment already received by A before his death would have become part of his other inheritable assets, such as cash or bank deposits.

- Valuation Consistent with Claim: Consequently, for the purpose of calculating the heirs' taxable inheritance value, the value attributable to the subject land transaction should be considered equivalent to the amount of this remaining sales proceeds claim (¥29,397,000). The Supreme Court concluded that the Tokyo High Court's decision to use this amount (¥29,397,000) as the basis for valuation, and then allocate it among the heirs according to their respective inheritance shares, was correct in its ultimate conclusion regarding the taxable value, even though the High Court had characterized it as the value of the "land" under special circumstances.

Key Principles and Implications

This Supreme Court decision, along with a parallel ruling issued on the same day concerning the estate of a deceased buyer in a similar uncompleted land transaction (Supreme Court, Showa 57 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 18), had significant implications:

- Shift to Economic Substance over Formal Title: These rulings marked a pivotal jurisprudential shift in Japanese inheritance tax law. Previously, tax practice often placed heavy emphasis on the formal legal ownership of land at the moment of death. This decision, however, prioritized an assessment of the economic substance of the deceased's interest. Even if legal title had not formally passed, if the transaction was substantially advanced and the seller's remaining interest was effectively a right to receive cash, then that right to cash (or its value) is what becomes subject to inheritance tax.

- Valuation Based on Transaction Price: In cases of incomplete sales, the inherited interest—whether it's the seller's claim for outstanding proceeds or the buyer's right to acquire the land—is generally to be valued based on the agreed-upon transaction price in the sales contract, rather than necessarily relying on the often lower official land valuation figures (rosenka, etc.). This aligns the tax valuation more closely with the actual economic value being transferred.

- Striving for Consistency in Seller and Buyer Scenarios: The Supreme Court aimed to establish a more consistent approach, regardless of whether it was the seller or the buyer who died mid-transaction. In the parallel buyer-side case, the Court held that the deceased buyer's inheritable asset was the contractual right to obtain the land (土地の所有移転請求権等 - tochi no shoyū iten seikyūken tō), and this right was to be valued at the land's acquisition price as stipulated in the sales contract.

- Impact on Tax Administration and Practice: Following these Supreme Court rulings, Japanese tax administration practices evolved. Generally, if a seller or buyer dies after a land sale contract is signed but before the physical handover of the land (or before the relevant regulatory approvals, such as for agricultural land conversion, if applicable, are finalized in a way that determines effective transfer of control/benefits), the inherited asset is now typically treated as the outstanding sales proceeds claim (in the case of a deceased seller) or the land acquisition right (in the case of a deceased buyer). Both are generally valued at the contract price.

- Limitations and Fact-Specific Nature: Legal commentators have noted that the Supreme Court's ruling in this specific case might be considered a "事例判断" (jirei handan), meaning its direct applicability could be limited by the unique facts presented. For instance, if the sale contract was at a much earlier stage, or if the seller's right to receive the remaining proceeds was not yet definitively established or was subject to significant contingencies at the time of death, the land itself might still be considered the primary inherited asset. Indeed, a subsequent Tax Tribunal decision reached such a conclusion where the seller's right to the remaining proceeds was deemed not yet definitively attributable to the deceased. Furthermore, cases where heirs have subsequently rescinded the sales contract after the inheritance have also led to different outcomes in lower courts, where the land itself was treated as the inherited property.

Current Practice and Lingering Questions

While the principles from these 1986 Supreme Court decisions have largely shaped current tax practice, some nuances remain. For example, legal commentary points out that current tax administration sometimes allows the heirs of a deceased buyer (as opposed to a seller) to report the land itself as the inherited property (valued using official methods) under certain circumstances. This may be for practical administrative reasons or in situations where the contract might not ultimately be fulfilled. Such exceptions, however, can raise questions about perfect consistency in the application of the economic substance principle across all scenarios.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1986 decision in this case involving an uncompleted land sale at the time of the seller's death was a crucial development in Japanese inheritance tax law. It firmly established that the determination of the taxable inherited property should look beyond mere formal legal title to the economic substance of the deceased's remaining interest. In such pending sales, the seller's inheritable asset is generally considered to be the right to the outstanding sales proceeds, valued at the agreed transaction price. This ruling underscores a pragmatic approach that seeks to align tax consequences with economic realities, particularly when official valuation methods for assets like land can significantly diverge from their actual market values demonstrated in recent, arm's-length transactions.