Lack of Public Notice for New Share Issuance: A Ground for Nullity, Japanese Supreme Court Rules

Judgment Date: January 28, 1997

Case: Action for Confirmation of Non-Existence and Nullity of New Share Issuance (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

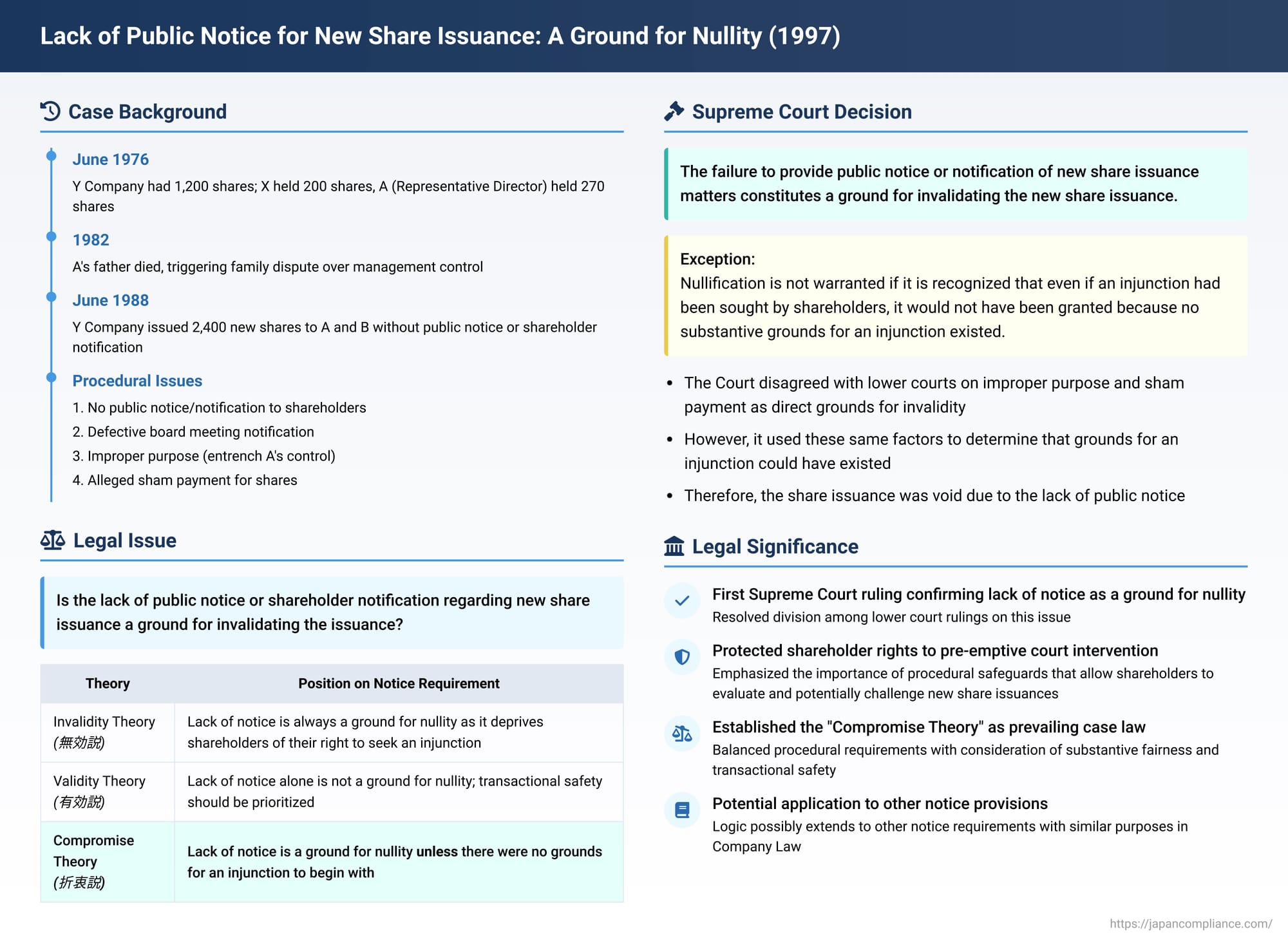

This 1997 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed a critical procedural aspect of issuing new shares: What happens if a company fails to provide the legally required public notice or notification to its shareholders about the terms of a new share offering? The Court concluded that such an omission can indeed be a ground for invalidating the entire share issuance, albeit with an important caveat.

Factual Background: A Family Feud and a Disputed Share Issuance

The case involved Y Company, a family-controlled business where A was the representative director, though A's father had historically held the actual power.

- Shareholding Structure and Dispute: As of June 1976, Y Company had 1,200 issued shares. A was the largest shareholder with 270 shares, and X (A's nephew and the plaintiff in this case) held 200 shares. Following the death of A's father in 1982, a significant dispute over management control erupted within the family. (A related 1979 share issuance by Y Company was also the subject of a separate Supreme Court case).

- The 1988 New Share Issuance: In June 1988, Y Company issued 2,400 new shares. These shares were subscribed to by A and another individual, B. This share issuance, however, was plagued by several alleged procedural and substantive issues:

- (1) Lack of Public Notice: No public notice or notification to shareholders regarding the terms of the new share issuance was made, as required by Article 280-3-2 of the Commercial Code then in effect.

- (2) Defective Board Resolution: One director was reportedly not properly notified of the board of directors' meeting at which the new share issuance was resolved.

- (3) Improper Purpose: The share issuance was allegedly orchestrated by A primarily to solidify their own control over Y Company in anticipation of an upcoming shareholders' meeting.

- (4) Lack of Genuine Capital Contribution: It was contended that the subscribers, A and B, did not make a genuine payment for the new shares, meaning there was no real increase in the company's capital (a situation often referred to as a "sham payment" or misekin).

- Legal Challenge: X filed a lawsuit seeking to have this 1988 new share issuance declared void.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The Kanazawa District Court (first instance) ruled the share issuance void. While acknowledging that procedural flaws like the lack of public notice or defective board meeting notice might not, on their own, be sufficient to invalidate an issuance made by the representative director, the court focused on the improper purpose (establishing A's control) and the lack of genuine capital contribution. Given these issues, and the fact that the new shares were issued only to A and B (meaning nullification would not unduly disrupt broader legal stability), the court found the issuance void.

- The Nagoya High Court, Kanazawa Branch (appellate court), largely affirmed the first instance decision on similar grounds. Y Company then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Nullity Based on Lack of Notice

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Company's appeal, thereby upholding the nullification of the share issuance, but it did so based on different reasoning than the lower courts.

The Supreme Court first addressed and dismissed some of the grounds relied upon by the lower courts:

- Improper Purpose: The Court stated that even if a new share issuance is conducted by a director with representative authority for a grossly unfair purpose (such as entrenching their own control), this alone is not a cause for invalidating the share issuance (citing a Supreme Court judgment from July 14, 1994).

- Lack of Genuine Capital Contribution (Sham Payment): Similarly, the Court noted that even in cases of sham payments, where it appears no genuine subscription occurred, the law (then Commercial Code Art. 280-13(1)) often deems the directors to have jointly subscribed to the shares. This does not automatically lead to the invalidity of the share issuance itself (citing a Supreme Court judgment from April 19, 1955).

However, the Supreme Court then focused critically on the lack of public notice or shareholder notification (defect (1) above):

- The Court reiterated that the purpose of requiring public notice or notification of new share issuance matters (under then Commercial Code Art. 280-3-2) is to guarantee shareholders the opportunity to exercise their right to seek an injunction to stop the share issuance (under then Commercial Code Art. 280-10) if it is unlawful or unfair. This principle was affirmed in a Supreme Court judgment from December 16, 1993.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the failure to provide such public notice or notification of new share issuance matters constitutes a ground for invalidating the new share issuance.

- There is an exception: nullification would not be warranted if it is recognized that even if an injunction had been sought by shareholders, it would not have been granted because no substantive grounds for an injunction actually existed.

- Applying this to the present case, the Court looked at the very issues of improper purpose (point (3)) and the lack of genuine contribution (point (4))—which it had just said were not direct causes of invalidity. It reasoned that these factors did suggest that, had X been properly notified and sought an injunction, grounds for such an injunction could have existed.

- Conclusion: Because it could not be said that there were no grounds for an injunction in this case, the failure to provide public notice (defect (1)) was indeed a valid reason to nullify the new share issuance.

Thus, although the Supreme Court disagreed with the primary reasoning of the lower courts, it upheld their ultimate conclusion that the share issuance was void, but on the specific ground of the lack of public notice.

Analysis and Implications: Protecting Shareholder Rights Through Procedural Safeguards

This 1997 Supreme Court decision was a pivotal moment in clarifying the consequences of failing to adhere to procedural requirements for new share issuances.

1. Significance of the Ruling:

Japanese company law (both the old Commercial Code and the current Company Law) provides a mechanism for shareholders to sue to nullify a new share issuance (Company Law Art. 828(1)(ii)) but does not explicitly list all the specific defects that can lead to nullification. Historically, courts tended to interpret these grounds narrowly to protect legal stability and the security of transactions. This Supreme Court judgment was the first to definitively state that a lack of the required public notice of "offering matters" (募集事項 - boshu jiko, as per then Commercial Code Art. 280-3-2, now covered by Company Law Art. 201(3) and (4)) constitutes a ground for nullity, subject to the exception noted. This resolved a point of division among lower court rulings and was subsequently followed by the Supreme Court (e.g., judgment on July 17, 1998).

2. The Purpose of Public Notice of Offering Matters:

The legal requirement for a company to publicly announce or notify its shareholders of the terms of a proposed share issuance (or disposal of treasury stock) serves a crucial purpose: it is designed to inform shareholders before the issuance takes place. This advance information enables them to scrutinize the proposal and, if they believe it to be unlawful or unfair (e.g., an excessively dilutive or unfairly priced issuance), to exercise their right to seek a court injunction to stop it (Company Law Art. 210; then Commercial Code Art. 280-10). This mechanism aims to ensure that share issuances are conducted lawfully and fairly. It is important to note that the current Company Law exempts non-public companies from this specific public notice obligation (Company Law Art. 201(3), (4)).

3. Competing Legal Theories on the Effect of Lacking Public Notice:

The legal effect of issuing new shares without the required public notice had been a subject of academic debate:

- Invalidity Theory (無効説 - muko setsu): This view prioritizes the shareholder's right to seek an injunction. The lack of notice unfairly deprives shareholders of this opportunity, and therefore, the share issuance itself should be considered void. Several lower court decisions had adopted this stance.

- Validity Theory (有効説 - yuko setsu):

- One version (Validity Theory ①) strongly emphasizes transactional safety, arguing that a lack of notice should not invalidate the share issuance. Proponents of this view often extend this to say that even issuances conducted through grossly unfair methods should not be voided, again for reasons of transactional security.

- Another version (Validity Theory ②) suggests that the validity of the share issuance should hinge on more substantive defects rather than the lack of notice alone. Procedural flaws that do not directly harm existing shareholders' core interests should not lead to nullification. However, those who hold this view generally agree that a share issuance conducted through grossly unfair methods would be a ground for nullity. The High Court's reasoning in the present case leaned towards this second version of the Validity Theory.

- Compromise Theory (折衷説 - setchu setsu) - Adopted by the Supreme Court:

- The version adopted by the Supreme Court in this 1997 judgment (Compromise Theory ①) holds that, in principle, the lack of public notice is a ground for invalidating the new share issuance because it undermines the statutory mechanism for shareholders to seek an injunction. However, it introduces an exception: if the company can prove that no grounds for an injunction existed even if proper notice had been given, then the share issuance will not be nullified. This approach had gained traction in many lower court decisions prior to this Supreme Court ruling, and this judgment effectively solidified it as the prevailing case law for such situations.

- Another variant (Compromise Theory ②) also treats lack of notice as making the issuance void in principle, but frames the exception differently: the defect is "cured" if the company proves there are no other substantive grounds for invalidity (essentially shifting the burden of proof regarding unfairness to the company).

4. Relevance to Other Notice Provisions:

The logic underpinning this Supreme Court judgment—that failing to provide a notice designed to enable shareholders to seek an injunction can be an invalidity ground—has potential implications for other notice requirements in the Company Law. For instance, Company Law Art. 202(4) mandates that shareholders be notified of the terms of a rights offering at least two weeks before the subscription deadline. A 2015 Osaka District Court decision, explicitly citing the 1997 Supreme Court judgment, held that a violation of this notice requirement is also a ground for invalidating the share issuance unless it can be shown that no grounds for an injunction existed.

5. Critique of the Supreme Court's Overall Approach :

The question of what constitutes a ground for invalidating a new share issuance should ideally be resolved by balancing the nature of the defect and the interests infringed against the need for transactional safety. Generally, only flaws that are fundamental to the "existence" of the new shares (e.g., issuing shares beyond the company's authorized limit, or issuing shares of a type not permitted by the articles of incorporation) or those that directly infringe upon the core interests of existing shareholders should lead to nullification.

From this perspective, the commentator argues that a "grossly unfair method" of issuance (like the alleged improper purpose in point (3) of this case) should be considered a ground for nullity. Conversely, the mere lack of public notice, being a procedural defect that does not in itself directly harm existing shareholder interests, should arguably not be a primary ground for nullification. (This view aligns with Validity Theory ②).

The commentator observes that the Supreme Court's general stance appears to be to limit grounds for invalidity to protect transactional safety, while simultaneously treating the deprivation of the opportunity to seek an injunction (caused by lack of notice) as an invalidity ground. This is contrasted with a reluctance to void issuances due to "grossly unfair methods" if the basic procedures were followed.

Many cases involving a lack of notice, including this one, often have at their core a dispute over company control, which raises the question of whether the issuance was conducted in a grossly unfair manner. The commentator finds a potential imbalance in the Supreme Court's approach: making a procedural notice defect a ground for nullity in principle, while not consistently treating substantively unfair issuances (e.g., those for improper control purposes) as direct grounds for nullity. This perceived imbalance is particularly relevant given that "public companies" under the Company Law can include many SMEs not listed on an exchange.

Conclusion: Emphasizing Shareholder Opportunity for Pre-emptive Action

The 1997 Supreme Court judgment established that a company's failure to provide the legally mandated public notice or shareholder notification regarding the terms of a new share issuance can indeed lead to the nullification of that issuance. The key exception is if the company can demonstrate that, even with proper notice, no legitimate grounds for a shareholder to obtain an injunction against the issuance would have existed. This ruling underscored the importance of the procedural safeguards designed to allow shareholders to seek pre-emptive court intervention against potentially unlawful or unfair share issuances. While the Court in this specific case dismissed improper purpose and sham payment as direct grounds for invalidity, it used these very factors to conclude that grounds for an injunction likely existed, thus making the lack of notice a fatal flaw. The decision continues to inform discussions on the appropriate balance between procedural regularity, substantive fairness, shareholder protection, and the stability of corporate transactions.