Knowing Your Tormentor: A 1973 Japan Supreme Court Ruling on When the Clock Starts Ticking for Tort Claims

Date of Judgment: November 16, 1973

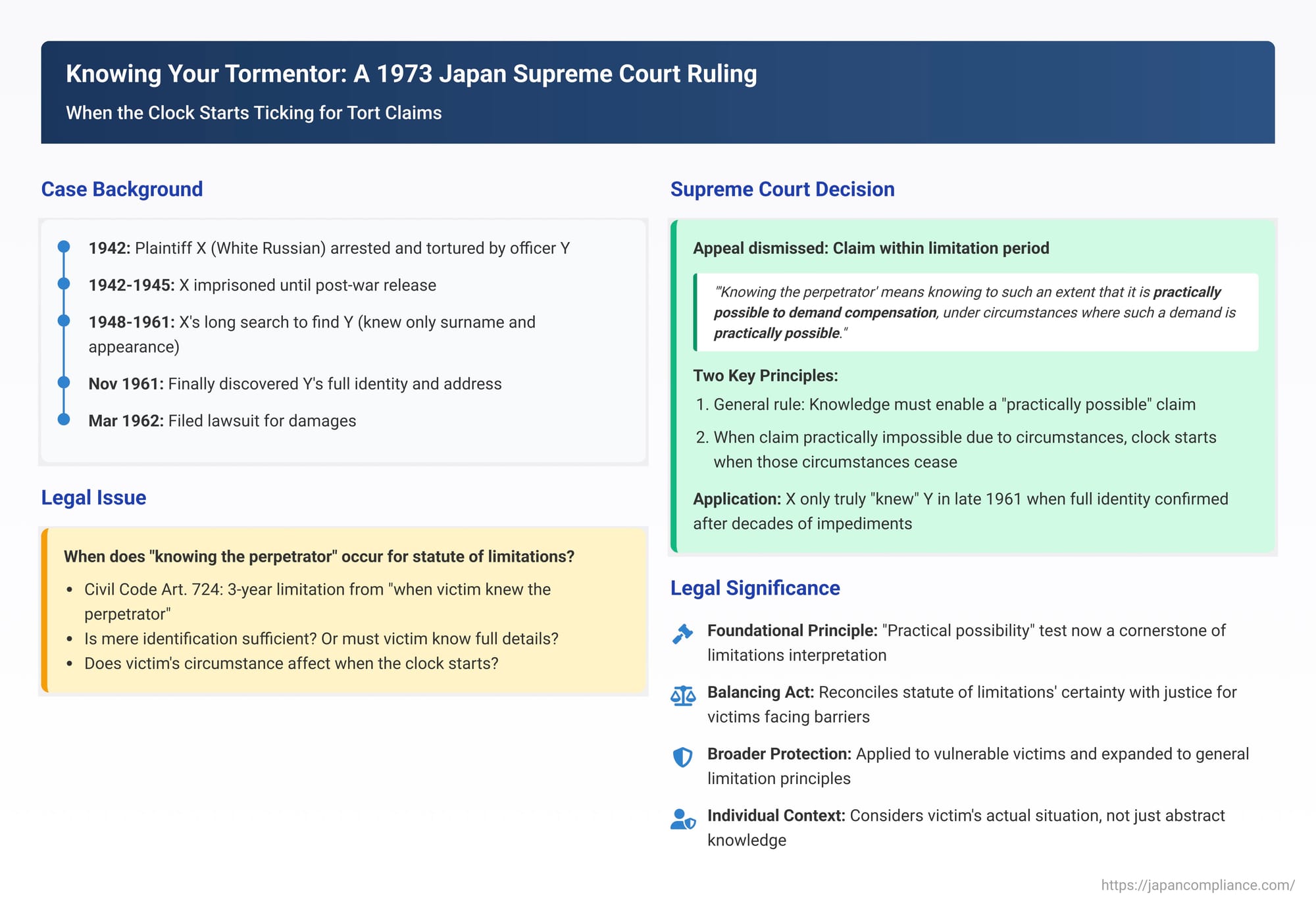

The statute of limitations in tort law dictates the period within which a victim must file a claim for damages. A common starting point for this period is when the victim becomes aware of both the harm they have suffered and the identity of the person who caused it. But what does it truly mean to "know the perpetrator"? Is it enough to know their face or surname? Or must the victim possess their full name and address before the clock starts ticking? And what if circumstances make it practically impossible for the victim to seek redress, even if they have some information about their tormentor? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed these profound questions in a landmark decision on November 16, 1973 (Showa 45 (O) No. 628), a case born from a harrowing pursuit of justice spanning decades.

The Facts: A Decades-Long Ordeal and a Difficult Search

The plaintiff, X, a White Russian, faced an unimaginable ordeal. In early 1942 (Showa 17), he was arrested under suspicion of violating the Military Secrets Protection Law and detained at Police Station A. During his interrogations, which lasted until April 16, 1942, X endured multiple assaults—the "tortious acts" central to the case—at the hands of several police officers, one of whom was Y. Under duress, X signed a confession. Subsequently, he was convicted of violating the Military Secrets Protection Law, and following the finalization of his sentence, he remained imprisoned until his release on September 4, 1945, amidst the chaos of post-war Japan.

At the time of the assaults, X knew Y's surname and his position as a police inspector at Station A, as well as his appearance. However, he did not know Y's first name or his address.

Upon his release, X embarked on a painstaking search for the officers who had brutalized him. It was a slow and arduous process. Around 1948 (Showa 23), he learned that Y might be residing in Akita Prefecture. By approximately 1951 (Showa 26), he had discovered Y's first name. X's persistence led him to inquire with a Human Rights Division of a Legal Affairs Bureau. In a letter dated November 8, 1961 (Showa 36), he was informed that Y had previously lived at an address in Akita Prefecture but had since moved to Tokyo, though his new Tokyo address was unknown. Undeterred, X continued his investigation based on these leads, eventually locating Y's current address in Tokyo and confirming that this was indeed the man who had assaulted him.

Having finally pinpointed his perpetrator, X filed a lawsuit against Y on March 7, 1962 (Showa 37), seeking compensation for both property damage and the profound psychological suffering he had endured. In response, Y denied the assaults and, crucially, argued that X's claim for damages was barred by the statute of limitations.

The appellate court, overturning the first instance, found that the statute of limitations had not expired and awarded X damages for emotional distress, leading Y to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Interpretation of "Knowing the Perpetrator"

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the lower court's decision that the claim was not time-barred. In doing so, the Court provided a highly influential interpretation of Article 724 of the Civil Code (the provision governing the statute of limitations for tort claims at the time), specifically the phrase "the time when the victim came to know the perpetrator" (加害者ヲ知リタル時 - kagaisha o shiritaru toki).

The Court's reasoning can be understood through two key points:

1. The General Principle: Knowledge Enabling a Practically Possible Claim (Point I)

The Court first laid down a general principle: "The phrase 'the time when the victim came to know the perpetrator' in Article 724 of the Civil Code, considering the purpose of establishing a special rule for the starting point of the statute of limitations in that article, should be construed to mean the time when the victim came to know the perpetrator to such an extent that it is practically possible to demand compensation from the perpetrator, under circumstances where such a demand is practically possible."

This principle (Point I of the judgment) has been widely recognized as profoundly important, becoming a cornerstone for subsequent case law and academic discourse on the statute of limitations in torts. It shifts the focus from mere abstract awareness of the perpetrator's identity to a more practical assessment of the victim's ability to actually pursue a claim.

2. Elaboration for Specific Circumstances: Overcoming Practical Impossibility (Point II)

The Court then elaborated on how this principle applies when a victim faces significant obstacles: "If, at the time of the tortious act, the victim did not precisely know the perpetrator's name and address, and moreover, if it was practically impossible under the circumstances at that time to exercise the right to demand compensation against them, then 'the time when the victim came to know the perpetrator' should be deemed to be when those circumstances cease and the victim confirms the perpetrator's name and address."

Application to X's Case:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court meticulously reviewed X's long journey. X knew Y's surname, rank, and appearance in 1942 but lacked crucial details like his first name and address. More importantly, X was continuously detained under the pre-war legal system, prosecuted, convicted, and imprisoned until September 1945, emerging into a Japan still reeling from the war's aftermath. The Court acknowledged that it was exceedingly difficult for X to ascertain Y's full identity and whereabouts both before and immediately after his release.

X's diligent efforts—learning Y might be in Akita around 1948, discovering Y's first name around 1951, and finally, through official inquiries and further investigation, pinpointing Y's Tokyo address and confirming his identity around November 1961—were crucial. The Supreme Court concluded that X truly "came to know the perpetrator" in the sense required by Article 724 only at this point in late 1961. Since X filed his lawsuit on March 7, 1962, this was within the three-year statute of limitations (as it was then for tort claims from the point of knowing the perpetrator and damage), and thus his claim was not time-barred.

The Significance of "Practically Possible Circumstances"

The phrase "under circumstances where such a demand is practically possible," introduced in Point I of the judgment, has had a lasting impact. It signifies that the starting point of the statute of limitations is not determined by a rigid, formalistic test of what the victim "knows," but also considers the victim's actual, concrete situation and whether it is reasonable to expect them to pursue a claim.

This means that even if a victim possesses some information that could theoretically identify the perpetrator, the statute of limitations may not begin to run if the victim's personal circumstances make it socially or practically unreasonable to expect them to initiate legal action. Subsequent legal interpretations and academic analyses have emphasized this aspect, suggesting that if a "reasonable person" in the victim's shoes could not fairly be expected to sue, the condition of "knowing" for limitations purposes may not be met.

Examples of how this principle has been applied or understood in later contexts include:

- Victims Wrongly Accused: A victim who is themselves a defendant in a related criminal case (e.g., a traffic accident where they are wrongly accused) might not be expected to sue the actual perpetrator until their own name is cleared through acquittal. The psychological and practical barriers to suing while under criminal prosecution can render the claim "practically impossible" for a time.

- Vulnerable Individuals: In cases involving vulnerable individuals, such as an intellectually disabled person abused by their employer, the statute of limitations might not commence until the victim is free from the coercive environment and has received assistance or explanation that enables them to act.

- Unlawful Litigation as Tort: Where the tort itself is an act of unlawful litigation, it is often difficult for the victim to sue for damages until the unlawfulness of that initial litigation is formally established by a court. Thus, the finalization of the related case often marks the starting point for the statute of limitations.

X's situation during his long detention under the pre-war regime and the immediate post-war chaos was an extreme example of such "practically impossible circumstances".

What Does "Knowing the Perpetrator" Entail? More Than Just a Name

It is important to note that this Supreme Court ruling does not establish a blanket rule that a victim must always know the perpetrator's full name and current residential address for the statute of limitations to begin. Academic commentary and even judicial analysis accompanying this specific case have clarified that this was a highly fact-specific determination due to X's extraordinary circumstances.

The prevailing understanding, consistent with legal scholarship before and after this ruling, is that "knowing the perpetrator" generally means having sufficient information to identify them as the party responsible for the harm and against whom a claim can be directed. If a victim can identify the perpetrator to this extent, and can reasonably ascertain further necessary details (like full name or address) through ordinary and accessible means of investigation, the clock may start to run at that point. The extreme difficulty X faced in identifying Y, compounded by his imprisonment and the societal upheaval, was what led the Court to conclude that he only truly "knew" Y in the legal sense in 1961.

Legacy and Broader Impact of the 1973 Ruling

While the specific factual narrative of X's decades-long pursuit of Y was unique and harrowing, the legal principle articulated in Point I of the judgment has had a broad and enduring legacy in Japanese tort law. This principle—that "knowing the perpetrator" is tied to the practical possibility of making a claim under circumstances where it is practically possible to do so—has become a foundational element in interpreting the statute of limitations.

Later Supreme Court decisions have consistently cited and applied this principle, extending its logic not just to the requirement of "knowing the perpetrator" but to the composite requirement of "knowing the damage and the perpetrator". This allows courts a degree of flexibility to consider the individual victim's circumstances, preventing the statute of limitations from becoming an unjust bar to claims where victims faced genuine, substantial impediments to seeking timely redress. The principles from this judgment are even considered influential in interpreting the general statute of limitations for claims under Article 166(1)(i) of the Civil Code.

Conclusion: Justice Tempered with Pragmatism

The Supreme Court's decision of November 16, 1973, is a powerful testament to the law's capacity to adapt to ensure fairness, particularly for victims who have faced extraordinary obstacles in their quest for justice. By defining "knowing the perpetrator" not in purely abstract terms but through the lens of practical possibility and reasonable expectation, the Court introduced a vital element of pragmatism into the application of the statute of limitations. This ruling underscores that the right to seek compensation for wrongs suffered should not be prematurely extinguished when circumstances beyond a victim's control render the pursuit of such a claim practically impossible. It remains a key precedent, guiding courts in the delicate task of balancing the need for legal certainty with the imperative of achieving just outcomes in individual cases.