Knowing When to Sue: Japan's Supreme Court on Timelines for Challenging Partial Information Disclosure

A First Petty Bench Ruling from March 10, 2016

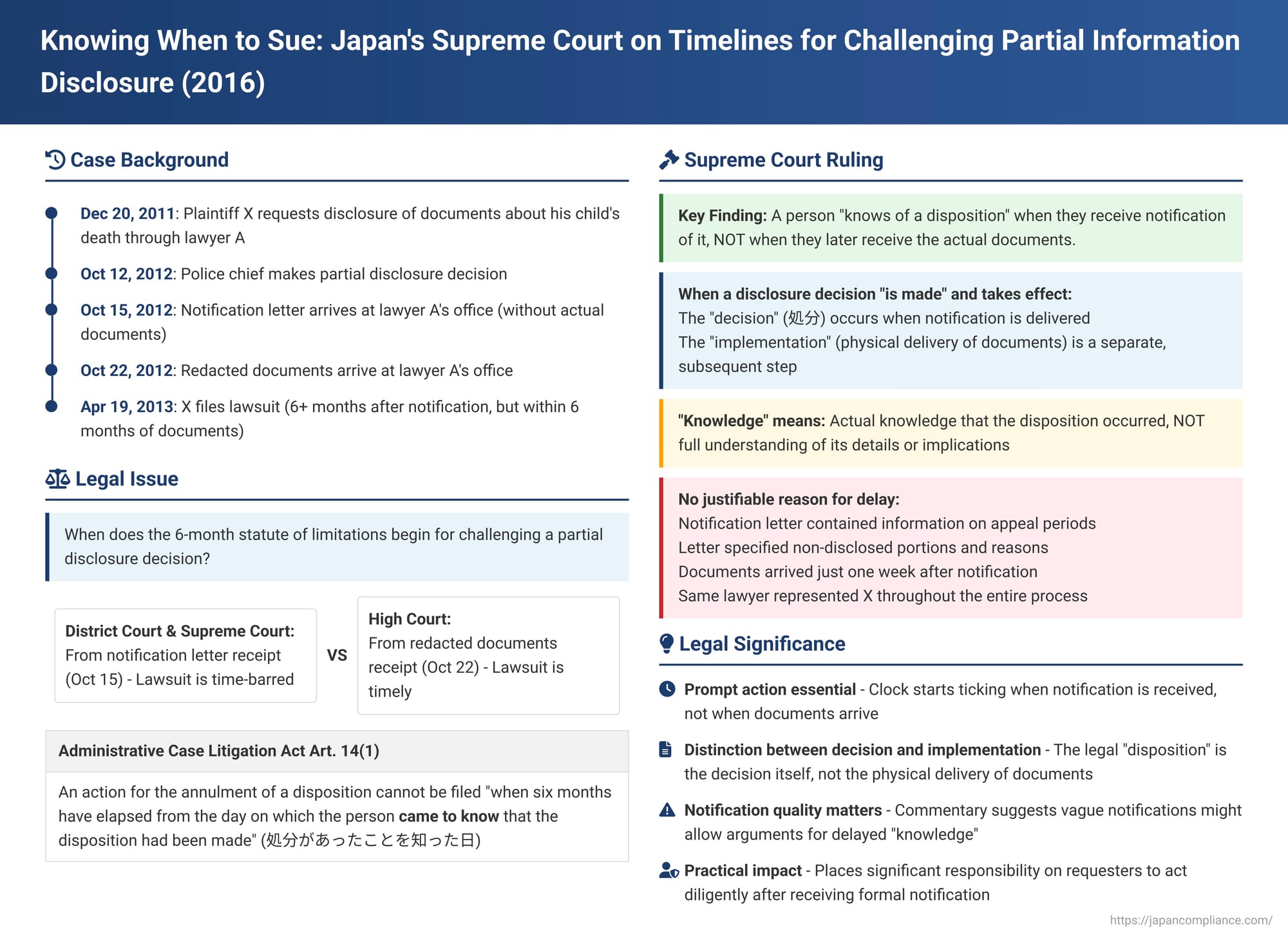

In legal systems around the world, the ability to challenge government decisions is a cornerstone of accountability, but this right is almost always subject to time limits, often referred to as statutes of limitations. Knowing precisely when this time limit begins to run is crucial for any individual or entity seeking judicial review. A 2016 decision by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan (Heisei 27 (Gyo Hi) No. 221) provided important clarification on this point in the context of information disclosure requests, specifically addressing when a person is deemed to have "known" about a partial non-disclosure decision for the purpose of calculating the period to file a lawsuit.

The Case: A Father's Quest for Information and a Delayed Lawsuit

The plaintiff, X, was seeking information related to the tragic death of his child, who had fallen from a building. On December 20, 2011, acting through his lawyer, A, X submitted a request to the Chief of the Kyoto Prefectural Police Headquarters (the "disposing administrative agency"). This request was made under the Kyoto Prefectural Personal Information Protection Ordinance (hereinafter "the Ordinance") and sought disclosure of all documents created or obtained by the Kyoto Prefectural Police Tanabe Police Station concerning the child's death. X was requesting this information as his "own personal information."

After some initial procedural steps (including an earlier decision that the child's information was not X's, and a separate voluntary provision of some documents related to the child), the police chief, following a local court ruling in another case that recognized an heir's right to request a deceased person's information as their own, revised this stance. On October 12, 2012, the police chief made a new formal decision (referred to as "the present disposition" - 本件処分 honken shobun) to partially disclose documents containing information about X's child, recognizing it as X's personal information.

The notification of this October 12 decision unfolded in stages:

- October 12, 2012 (Phone Call): A representative from the Kyoto Prefectural Police telephoned X's lawyer, A. In this call, the representative informed lawyer A that the redacted documents to be formally delivered under this new decision (hereinafter "the present disclosed documents" - 本件各開示文書 honken kaku kaiji bunsho) would be identical in content to the documents that lawyer A had already received through the voluntary provision on October 3.

- October 15, 2012 (Notification Letter Arrives): The official written notification (通知書 - tsūchisho) of the October 12 partial disclosure decision was delivered to lawyer A's office. This letter explicitly stated that it was the response to X's disclosure request and that a partial disclosure was being made. According to the record, this letter also specified which portions of the requested documents were not being disclosed and provided the reasons for non-disclosure. However, the letter did not physically include the redacted documents themselves; it indicated that the actual disclosure (i.e., delivery of the document copies) would be done by mail at a later date and time.

- October 22, 2012 (Redacted Documents Arrive): The actual redacted documents (the "present disclosed documents") were delivered to lawyer A's office.

On April 19, 2013, X, again represented by lawyer A, filed a lawsuit against Y (Kyoto Prefecture). The suit sought the annulment of the non-disclosed portions of the October 12 decision and also requested a court order mandating the disclosure of the withheld information. This filing date was crucial: it was more than six months after October 15, 2012 (the date the notification letter was received), but less than six months after October 22, 2012 (the date the actual redacted documents were received).

The Legal Sticking Point: When Did the Clock Start Ticking?

The case turned on Article 14, paragraph 1 of Japan's Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA). This provision states that an action for the annulment of an administrative disposition cannot be filed "when six months have elapsed from the day on which the person came to know that the disposition had been made" (処分があったことを知った日 - shobun ga atta koto o shitta hi), unless there is a "justifiable reason" (正当な理由 - seitō na riyū) for the delay.

The Kyoto District Court (first instance) dismissed X's lawsuit as untimely. It held that the six-month statute of limitations began to run on October 15, 2012, when lawyer A received the formal notification letter, as X (through his lawyer) knew of the disposition on that date.

However, the Osaka High Court (second instance) reversed this decision. It reasoned that the notification letter alone, without the actual redacted documents, did not make the full extent of the non-disclosure clear. The High Court viewed the notification letter and the subsequently delivered redacted documents as together constituting the notification of the disposition's content. Therefore, it concluded that X "knew that the disposition had been made" only on October 22, 2012, when the documents arrived, making the lawsuit filed on April 19, 2013, timely. Kyoto Prefecture appealed this appellate ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of March 10, 2016

The Supreme Court's First Petty Bench reversed the Osaka High Court's decision and upheld the District Court's original dismissal of the lawsuit as untimely.

Key Rulings by the Supreme Court:

- When a Disclosure Decision "Is Made" and Takes Effect: The Court first clarified when the administrative "disposition" (the partial non-disclosure decision) legally occurred and took effect. Under the Kyoto Prefectural Personal Information Protection Ordinance, the "implementation of disclosure" (e.g., the physical delivery of document copies, governed by Article 16 of the Ordinance) is a procedural step that follows the formal "disclosure decision" (開示決定等 - kaiji kettei-tō, governed by Article 15). Therefore, a disclosure decision under the Ordinance takes legal effect at the moment the notification letter detailing that decision reaches the requester, even if the actual redacted documents have not yet been delivered. In this case, the October 12 partial disclosure decision legally "was made" (処分があった - shobun ga atta) and took effect on October 15, 2012, when the notification letter arrived at lawyer A's office.

- When a Requester "Knew that the Disposition Had Been Made": The Court then addressed the crucial phrase from ACLA Article 14(1). Citing established precedents (Supreme Court, November 20, 1952, and Supreme Court, October 24, 2002 ), it stated that for administrative dispositions individually notified to the addressee, the day on which the person "knew that the disposition had been made" refers to the day the person actually knew that the disposition had occurred. Significantly, the Court clarified that this "knowledge" does not require the person to have a full understanding of "the detailed content of the disposition or its adverse nature, etc." (当該処分の内容の詳細や不利益性等の認識までを要するものではない).

The October 12 partial disclosure decision was formally notified to X via the notification letter received by lawyer A on October 15. The Court emphasized that the case record showed this notification letter clearly stated it was a response to X's disclosure request and that a partial disclosure was being made. Furthermore, the letter specified the portions of the documents that were not being disclosed and provided the reasons for their non-disclosure.

Given these facts, the Supreme Court concluded that X (through his lawyer A) "actually knew that the disposition had been made" on October 15, 2012. - Timeliness of the Lawsuit: Since X knew of the disposition on October 15, 2012, the six-month period for filing an annulment action under ACLA Article 14(1) began on that date. Consequently, the lawsuit filed on April 19, 2013, was initiated after this six-month period had expired.

- No "Justifiable Reason" for Delay: The Court also briefly addressed the possibility of a "justifiable reason" for the late filing under the proviso of ACLA Article 14(1). It noted that the notification letter itself contained information about the period for filing an appeal (教示 - kyōji). The letter specified the non-disclosed portions and the reasons for non-disclosure. The actual redacted documents arrived only one week after the notification letter. Moreover, lawyer A had consistently represented X throughout the entire process, from the initial disclosure request to the filing of the lawsuit. Given these circumstances, the Court found no "justifiable reason" to excuse the delay in filing the suit.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that X's annulment action was time-barred and should be dismissed as unlawful. The claim for an order mandating disclosure, being dependent on the annulment action, was also deemed unlawful.

Understanding "Knowledge of Disposition" for Limitation Periods

This decision reinforces the Supreme Court's consistent interpretation of what it means for an individual to have "known that the disposition had been made" for the purpose of starting the statute of limitations.

- The standard is "actual knowledge" of the occurrence of the disposition.

- This does not necessarily equate to having a complete and detailed understanding of all aspects of the disposition, its full legal implications, or its precise adverse impact.

- The role of the official notification letter is paramount. If such a letter clearly communicates that a decision has been made, its nature (e.g., partial disclosure), and, as in this case, specifies the non-disclosed parts and the reasons, it is generally considered sufficient to impart the requisite "knowledge" to the recipient (or their legal representative) and thus to trigger the limitation period.

The Distinction Between "Decision" and "Implementation"

A key element in the Supreme Court's reasoning is the distinction between the formal administrative decision and the subsequent implementation of that decision.

- In information disclosure cases, the "decision" to disclose, partially disclose, or not disclose is a distinct legal act by the administrative agency, typically formalized in a written determination.

- The "implementation" of a disclosure decision (e.g., the physical act of providing copies of documents) is a subsequent procedural step.

The statute of limitations for challenging the decision begins to run from the point of knowing about the decision itself, not necessarily from the completion of its implementation.

What if the Notification Letter is Vague?

The legal commentary accompanying the source material raises an interesting point: what if the notification letter is extremely vague and provides little to no information about the scope of non-disclosure or the reasons?

- The commentary notes that in this particular case, the Supreme Court did observe that the notification letter did specify the non-disclosed parts and the reasons. This specificity was a factor.

- It speculates that if a notification letter were so deficient that it made it impossible to understand the nature or extent of the non-disclosure, an argument might be made that the recipient had not truly "known" of the (content of the) disposition merely upon receiving such an uninformative letter. In such a hypothetical scenario, the disposition might be argued to have a defect in the specification of its content, potentially delaying its legal effect until the content is clarified (e.g., by the arrival of the redacted documents).

- However, an alternative view mentioned in the commentary is that even if a notification is flawed (e.g., in its statement of reasons), it might still constitute "knowledge" of the disposition's occurrence for limitation purposes, and the flaw itself could then become one of the grounds for the annulment lawsuit (if filed in a timely manner).

In the present case, the Supreme Court was satisfied with the level of detail provided in the notification letter.

Significance of the Ruling for Information Requesters

This Supreme Court decision carries important practical implications for individuals and entities requesting information from government agencies in Japan:

- It underscores the critical importance of acting promptly upon receiving an official notification letter regarding a partial disclosure (or non-disclosure) decision, even if the actual disclosed documents are scheduled to be delivered later.

- The "knowledge" that starts the six-month clock for filing an annulment action is generally triggered by the awareness of the decision's existence and its basic nature, as conveyed by the official notification, rather than by the subsequent receipt and detailed analysis of all related materials.

- It also highlights the importance of administrative agencies providing clear and sufficiently detailed notifications that include information on appeal rights and applicable deadlines, as appears to have been done in this case.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2016 judgment in this personal information disclosure case provides a firm clarification on the starting point for the statute of limitations when challenging partial non-disclosure decisions. By emphasizing that "knowledge of the disposition" occurs when the recipient is aware of the decision itself, typically through a sufficiently clear notification letter, rather than at the later point of receiving the actual disclosed (redacted) documents, the Court places a significant responsibility on information requesters and their legal representatives to act diligently and within the prescribed timeframes once they are formally notified of an adverse or partially adverse administrative decision. This ruling reinforces the importance of understanding procedural timelines in administrative litigation.