Killer Beneficiary: No Insurance Payout Even Without Profit Motive, Says 1967 Japanese Supreme Court

Date of Judgment: January 31, 1967

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. 933 (o) of 1941 (Life Insurance Claim Case)

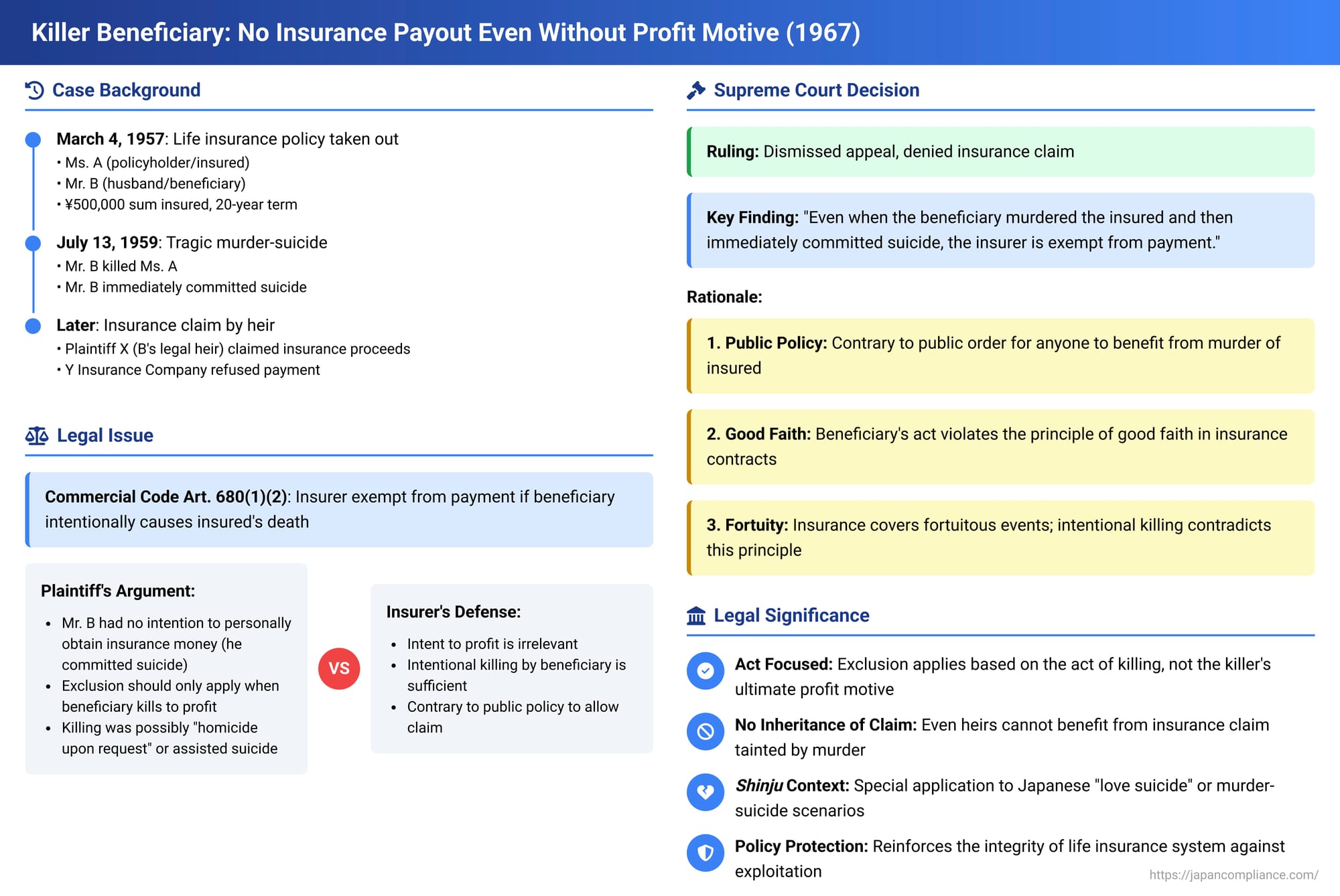

A fundamental principle in insurance law, often referred to as the "slayer rule," generally prevents a beneficiary who intentionally kills the insured from receiving the policy proceeds. But what happens in the tragic and complex scenario where the beneficiary kills the insured and then immediately commits suicide? Does the apparent lack of intent by the beneficiary to personally profit from the insurance alter the application of this rule? This was the grim question before the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant 1967 decision that underscored the strength of the public policy against beneficiaries causing the insured's death.

A Tragic Pact: Facts of the Case

The case originated from a life insurance policy taken out on March 4, 1957. Ms. A was the policyholder and the insured, and her husband, Mr. B, was the designated beneficiary. The policy, provided by Y Insurance Company, had a sum insured of 500,000 yen and a term of 20 years.

On July 13, 1959, a little over two years into the policy, Mr. B intentionally killed his wife, Ms. A. Immediately after murdering her, Mr. B took his own life.

The plaintiff in the subsequent lawsuit, X, was the sole legal heir of Mr. B and, as such, inherited all of Mr. B's rights and obligations. X filed a claim with Y Insurance Company for the life insurance proceeds. The argument was that upon Ms. A's death, Mr. B (as the beneficiary) acquired the right to the insurance claim, and upon Mr. B's subsequent death, this right passed to X by inheritance.

Y Insurance Company refused to pay the claim. The insurer invoked Article 680, paragraph 1, item 2 of the old Commercial Code (a provision corresponding to Article 51, item 3 of the current Insurance Act). This article exempted the insurer from the obligation to pay if the designated beneficiary intentionally caused the death of the insured.

X argued that Mr. B's act of killing Ms. A was either upon Ms. A's own request (a "homicide upon request" or shokutaku satsujin) or merely assistance to Ms. A's suicide (jisatsu hōjo). More crucially, X contended that because Mr. B committed suicide immediately after killing Ms. A, Mr. B had no intention of personally obtaining the insurance money. Therefore, X asserted, the exclusionary provision of the Commercial Code should not apply.

The Osaka District Court (first instance) dismissed X's claim. It reasoned that even if Ms. A's death was a homicide upon request or an assisted suicide, the inherent risk of such acts being induced by the prospect of insurance could not be entirely dismissed. The court stated that it would be contrary to the aleatory (chance-based) nature of an insurance contract to allow someone who foresaw and caused (or facilitated) the insured's death to claim insurance benefits as a result of that death, irrespective of the victim's consent or the killer's intent to acquire the insurance money. The Osaka High Court (second instance) upheld this decision for substantially similar reasons. X then appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the lower courts misunderstood the legislative intent of the exclusion, which X believed was solely to prevent beneficiaries from killing the insured in order to receive the insurance money—a motive absent in Mr. B's case due to his immediate suicide.

The Legal Issue: Intent to Profit vs. The Act of Killing

The central legal question was whether the insurer's exemption under Article 680, paragraph 1, item 2 of the old Commercial Code required proof that the beneficiary killed the insured with the specific motive of obtaining the insurance funds. Or was the intentional act of killing the insured by the beneficiary, regardless of the ultimate financial motive (especially when the beneficiary also died), sufficient to trigger the exemption?

The Supreme Court's Unwavering Stance

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions and thereby refusing the insurance claim.

The Court meticulously outlined the legislative rationale behind the Commercial Code provision (Art. 680(1)(2) regarding the exemption, and Art. 680(2) regarding the insurer's obligation to refund accumulated premiums to the policyholder in such cases). It stated that the provision exempting the insurer when the beneficiary intentionally kills the insured is based on several interconnected reasons:

- Public Policy (Anti-Public Interest): It is contrary to public policy for a person who has murdered the insured to obtain the insurance money. Allowing such a benefit would be socially unacceptable.

- Principle of Good Faith and Fair Dealing: Such an act by the beneficiary violates the principle of good faith and fair dealing that underpins insurance contracts.

- Fortuity of the Insured Event: The intentional killing of the insured by the beneficiary contravenes the requirement that the insured event (death) be, from the perspective of the contract, a fortuitous or accidental occurrence.

Based on these fundamental principles, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Therefore, even in cases like the present one, where the insurance beneficiary murdered the insured and then immediately committed suicide, meaning the murderer had no intent at the time of the killing to personally obtain the insurance money, the aforementioned legal provision applies, and it is appropriate to interpret that the insurer is exempt from the obligation to pay the insurance amount."

The Court found the High Court's judgment, which reached the same conclusion, to be legitimate and saw no error in its application of the law.

Unpacking the Rationale: Why Motive Doesn't Override the Exclusion

The Supreme Court's decision places strong emphasis on the wrongful nature of the beneficiary's act of intentionally causing the insured's death. The lack of a subsequent personal financial gain by the killer-beneficiary (due to their own death) was deemed irrelevant to the application of the exclusion.

The key takeaways from the rationale are:

- Focus on the Act, Not the Ultimate Benefit: The law is triggered by the beneficiary's "intentional causing of the insured's death." The provision does not require an additional inquiry into whether the beneficiary also intended to live to enjoy the proceeds.

- Upholding Public Policy: Allowing the estate of a killer-beneficiary to receive the insurance money, even if the killer did not personally benefit, would still be seen as an indirect benefit stemming from a wrongful act, which is contrary to public policy.

- Integrity of the Insurance Mechanism: The principle of good faith and the requirement of fortuity are essential to the functioning of insurance. When a beneficiary intentionally engineers the insured event, these principles are fundamentally breached.

Legal scholarship has extensively discussed the foundations of this exclusion. While the Supreme Court cited public policy, good faith, and fortuity, some scholars have debated the precise interplay and primary importance of these elements. For instance, some argue that "public policy" or "anti-public interest" is the sole or primary ground, focusing on the social unacceptability of a killer benefiting. Others have emphasized the good faith aspect, particularly given the aleatory nature of insurance contracts. More recent academic discourse has sometimes questioned the applicability of "good faith" violation directly to a beneficiary who is not a contractual party with the insurer, suggesting that "abuse of rights" by the beneficiary might be a more fitting framework alongside public policy. Regardless of these theoretical nuances, the outcome—that the act of killing itself is the disqualifying factor—is widely supported.

A minority of scholars, prioritizing survivor protection and defining "public policy" narrowly as preventing the killer beneficiary themselves from obtaining the money, have argued against insurer exemption in murder-suicide scenarios where no insurance acquisition intent by the killer is present. However, this view is criticized for potentially understating the broader public policy concerns.

Broader Implications and Scholarly Discussion

Consent Killings and Assisted Suicide:

The lower courts in this case had already determined that the exclusion would apply even if the killing was a homicide upon request or an assisted suicide. The Supreme Court's reasoning, by focusing on the intentional act of the beneficiary causing death, implicitly supports this. While an insured's own suicide might be covered by insurance after a contractually specified waiting period, the active, unlawful involvement of the beneficiary in causing the death—even with the insured's consent—introduces a different legal dynamic. Such acts (homicide upon request, assisted suicide) are themselves criminal offenses under Japanese law (Penal Code Art. 202). The beneficiary's commission of a crime to bring about the insured event strongly implicates public policy concerns.

The "Shinju" (心中) Context:

The facts of this case—a beneficiary killing the insured and then immediately committing suicide—are characteristic of what is known in Japan as shinju, a term often translated as joint suicide, love suicide, or, in darker forms, murder-suicide. While such cases involve complex socio-cultural and emotional factors, the legal analysis for insurance purposes tends to focus on the nature of the beneficiary's actions. Legal commentary distinguishes various shinju patterns:

- Simultaneous suicide of the insured and beneficiary.

- Consent-based shinju, which can include the beneficiary assisting the insured's suicide or a homicide upon request followed by the beneficiary's suicide.

- Non-consensual murder of the insured by the beneficiary, followed by the beneficiary's suicide (muri-shinju).

The latter two categories, where the beneficiary actively and unlawfully causes the insured's death, would generally fall under the beneficiary-slayer exclusion. The emphasis remains on the beneficiary's culpable act.

Alternative Legislative Approaches:

It is noteworthy that not all legal systems address this issue identically. For example, German insurance contract law (specifically §162 VVG) stipulates that if a third-party beneficiary intentionally and unlawfully causes the death of the insured, the beneficiary's designation is deemed ineffective. This means the insurance proceeds would typically be paid to the policyholder or, if the policyholder is the deceased insured, to the insured's estate. Some Japanese scholars have suggested that a similar legislative approach—treating the beneficiary designation as void rather than automatically exempting the insurer—might be worth considering. This could allow the proceeds to benefit the insured's innocent heirs via the estate, even if the beneficiary who committed the act would have been among those heirs.

Significance of the 1967 Ruling

The Supreme Court's 1967 decision was pivotal for Japanese insurance law:

- It definitively established that the beneficiary-slayer exclusion (under the old Commercial Code) applies even if the beneficiary's subsequent immediate suicide indicates a lack of intent to personally profit from the insurance money.

- It reinforced the robust public policy against any party benefiting, even indirectly through their estate, from the intentional killing of an insured person.

- It clarified that the critical factor for the exclusion is the beneficiary's intentional act of causing the insured's death, not their ultimate financial motive or whether they lived to receive the proceeds.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1967 Supreme Court judgment delivers a clear and stern message: the act of a life insurance beneficiary intentionally killing the insured is a fundamental breach that nullifies any claim to the policy proceeds. The Court's multi-pronged rationale—invoking public policy, good faith, and the fortuity of the insured event—underscores the gravity of such an act within the framework of insurance law. By confirming that the beneficiary's subsequent suicide and lack of personal enrichment motive do not alter this outcome, the decision upholds the integrity of the insurance system and reinforces strong societal prohibitions against profiting from homicide.