Keeping Executive Power in Check: Japan's Supreme Court on the Limits of Delegated Legislation in Land Reform

A Grand Bench Ruling from January 20, 1971

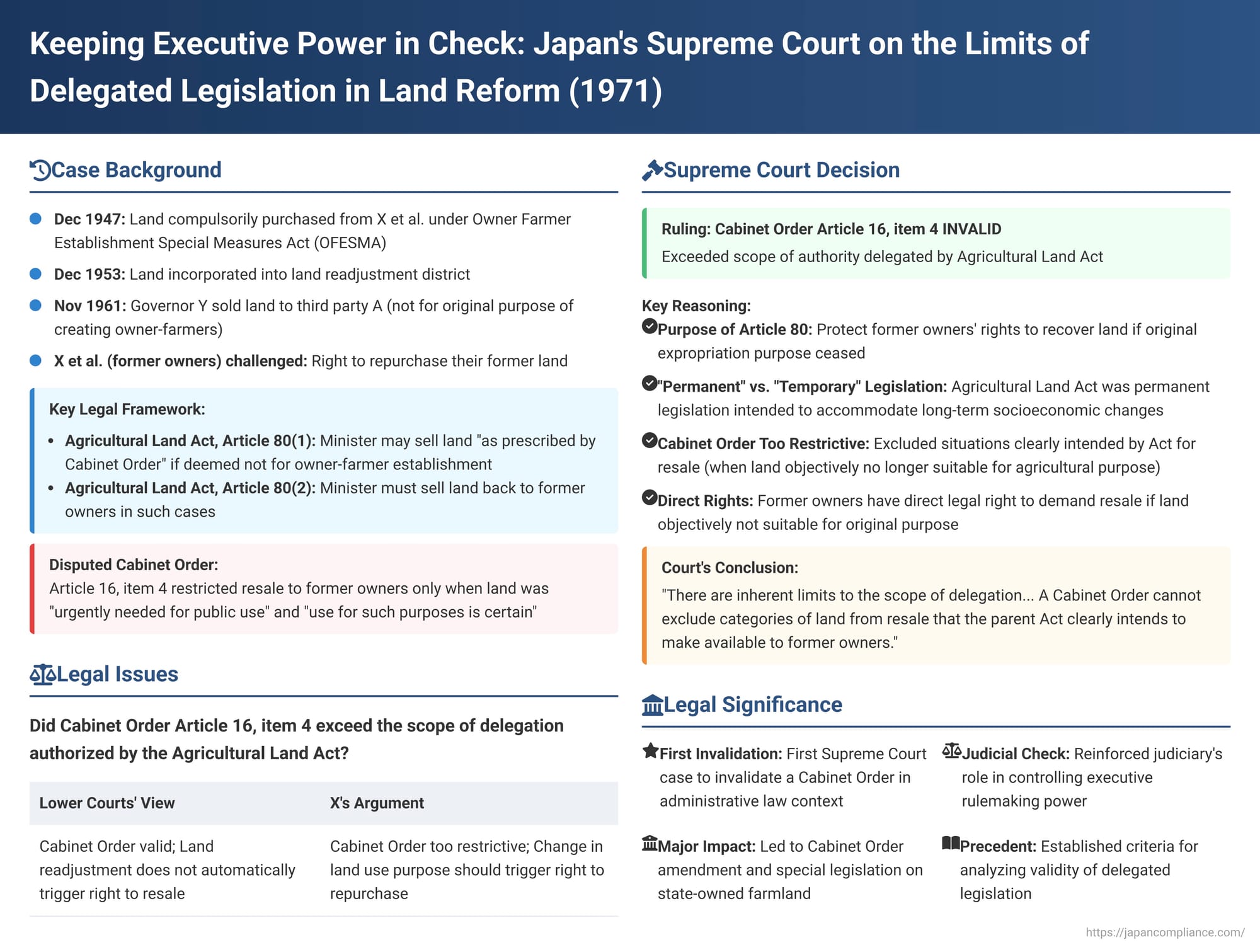

In modern states, legislatures often enact laws that empower executive bodies to create more detailed rules and regulations through cabinet orders or ministerial ordinances. This "delegated legislation" is a practical necessity for efficient governance, allowing for flexibility and technical expertise in rulemaking. However, it carries an inherent risk: executive bodies might overstep the authority granted to them by the primary legislation passed by the parliament. A landmark decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on January 20, 1971 (Showa 42 (Gyo Tsu) No. 52), powerfully addressed this issue, scrutinizing a Cabinet Order provision related to Japan's post-World War II land reforms and the conditions for reselling state-acquired farmland.

The Land in Question: A Legacy of Reform

The case involved agricultural land originally owned by X et al. (the plaintiffs/appellants). In December 1947, their land was compulsorily purchased by the State under the Owner Farmer Establishment Special Measures Act (OFESMA) (自作農創設特別措置法 - Jisaku-nō Sōsetsu Tokubetsu Sochi Hō). This Act was a cornerstone of the extensive land reforms undertaken in post-war Japan to democratize land ownership by transferring land from landlords to tenant farmers. However, in this instance, the purchased land was not subsequently resold to create new owner-farmers as initially intended.

Years later, in December 1953, the land was incorporated into a land readjustment district by approval of the Kyoto Regional Agricultural Administration Office Director. Then, in November 1961, Y, the Governor of Aichi Prefecture, acting under the subsequent Agricultural Land Act (農地法 - Nōchi Hō), sold the land in question to a third party, A, who was not a party to this specific lawsuit. X et al., the former owners, challenged this sale.

The Legal Framework for Resale to Former Owners

The dispute hinged on Article 80 of the Agricultural Land Act, which governed the disposal of land acquired under OFESMA but not used for its original purpose.

- Agricultural Land Act, Article 80(1) stated that if the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry deemed it appropriate that such land should not be used for the purpose of establishing owner-farmers or promoting agricultural land use, the Minister may sell it off or transfer its jurisdiction, "as prescribed by Cabinet Order". This phrase "as prescribed by Cabinet Order" indicated a delegation of authority to the executive to flesh out the details.

- Agricultural Land Act, Article 80(2) provided a crucial directive: in such cases (where the land was not to be used for the original land reform purpose), the Minister must sell the land back to the "former owner or their general successor" (旧所有者 - kyū shoyūsha), subject to certain exceptions not central to this part of the dispute.

- Agricultural Land Act Enforcement Order (Cabinet Order), Article 16, item 4 (農地法施行令第16条4号 - Nōchi Hō Shikōrei Dai Jūroku-jō Yon-gō): This provision of the Cabinet Order, enacted under the authority delegated by Article 80(1) of the Act, set specific conditions for when the Minister could make the determination that the land would not be used for establishing owner-farmers. It restricted this determination—and thus the possibility of resale to former owners—to situations where the land was "urgently needed for public use, public utility purposes, or facilities necessary for the stability of national life, and its use for such purposes is certain".

The Core Dispute: Did the Cabinet Order Go Too Far?

X et al. argued that this Cabinet Order provision (Rei Article 16, item 4) was unduly restrictive and narrowed the scope of their right to repurchase the land beyond what was intended by the parent Agricultural Land Act. They contended that the incorporation of their land into a land readjustment district, effectively changing its planned use, should have been sufficient for the Minister to determine that it was no longer for establishing owner-farmers, thereby triggering their right to repurchase under Article 80(2) of the Act. The lower courts, the Nagoya District Court and Nagoya High Court, had dismissed their claims, finding that the conditions of Rei Article 16, item 4 were not met and that the land readjustment did not automatically satisfy the requirements for resale to former owners.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision of January 20, 1971

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court overturned the decisions of the lower courts concerning the annulment of the resale disposition to A and remanded this part of the case to the Nagoya District Court for further proceedings. The Court's reasoning was a significant pronouncement on the limits of delegated legislation.

Interpretation of the Parent Act's Intent (Agricultural Land Act, Article 80):

The Supreme Court first delved into the purpose of Article 80 of the Agricultural Land Act.

- It found that Article 80 was designed to establish a system that protected the rights of former owners whose property had been compulsorily acquired by the state but was subsequently not used for the specific public purpose (in this case, creating owner-farmers) for which it was taken. The Court reasoned that if the original expropriation purpose ceased, there was no longer a compelling rational basis for the State to retain the land and dispose of it at its sole discretion. Instead, legislative policy rightly favored measures that allowed the former owner a right to recover their property.

- The Court acknowledged that Article 80(1) of the Act uses the permissive phrase "may sell." However, it pointed out that Article 80(2) employs the mandatory phrase "must sell" when it comes to reselling the land to former owners. Considering these two provisions together with the overall purpose of the resale system, the Supreme Court concluded that if objective facts demonstrated that the purchased farmland was no longer suitable for the purpose of establishing owner-farmers, the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry was bound (internally) to make such a determination and was obligated to sell the land back to the former owner. Consequently, the former owner possessed a legal right to demand repurchase from the Minister.

Invalidation of the Cabinet Order Provision (Rei Article 16, item 4):

This interpretation of the parent Act's strong protection for former owners' rights then led to the Court's crucial finding on the Cabinet Order:

- The Court recognized that Rei Article 16, item 4 explicitly limited the Minister's determination (that the land would not be used for owner-farmer creation) to instances where there was an "urgent need" for the land for new, specified "public purposes" and where its use for these new purposes was "certain". The intent of this Order provision appeared to be to prioritize the original land purchase objectives, allowing resale only when superseded by other pressing public needs.

- While Article 80(1) of the Act does delegate the task of defining the criteria for this determination to a Cabinet Order, the Supreme Court firmly stated that there are "inherent limits" (おのずから限度があり - onozukara gendo ga ari) to the scope of such delegation. A Cabinet Order, the Court asserted, cannot exclude categories of land from resale that the parent Act clearly intends to make available to former owners.

- A key element in the Court's reasoning was the distinction between the OFESMA, which was temporary legislation for the immediate post-war land reform, and the Agricultural Land Act, which was enacted as "permanent legislation" (恒久立法 - kōkyū rippō). As permanent legislation, Article 80 of the Act was presumed to be drafted to accommodate and address long-term social and economic changes.

- Given this permanent nature, the Court found it "naturally foreseeable" that situations would arise where purchased farmland, due to evolving societal or economic conditions, would lose its original significance as agricultural land and become more suitable for non-agricultural uses, even if not "urgently needed" for the specific "public uses" narrowly defined in Rei Article 16, item 4. The Court referenced Article 7(1)(iv) of the Agricultural Land Act itself, which dealt with the conversion of farmland to other uses, as an example of the Act recognizing such transformations.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Article 80 of the Act must be interpreted as obligating resale to former owners in these broader circumstances as well—that is, when the land is objectively no longer suitable for its original agricultural purpose, regardless of whether an urgent new public use has arisen.

- By restricting the Minister's ability to make this determination only to the narrow cases outlined in Rei Article 16, item 4 (urgent new public use) and thereby preventing such a determination in other objectively valid situations (e.g., general socio-economic change rendering the land non-agricultural), the Cabinet Order provision exceeded the scope of delegation authorized by Article 80 of the Agricultural Land Act and was, therefore, null and void.

The Court concluded that former owners have a direct right to demand resale from the Minister if facts objectively demonstrate that the land is no longer suitable for the purpose of creating owner-farmers, irrespective of whether the Minister has formally made an "Article 80(1) determination". If the Minister refuses, the former owners can pursue fulfillment of this obligation through civil litigation. Consequently, if a prefectural governor sells such land to a third party (as happened in this case), the former owner has legal standing to seek the annulment of that sale through administrative litigation. The case was remanded for the lower court to determine if such objective facts existed for the land in question.

What is "Delegated Legislation" and Its Limits?

Delegated legislation (委任命令 - inin meirei in Japanese, referring to orders based on delegation) is a common feature of modern legal systems. Primary laws (statutes) passed by the legislature often lay down general principles and then authorize executive bodies (like the Cabinet or ministries) to issue more detailed rules and regulations through orders or ordinances. This is done for reasons of efficiency, technical expertise, and flexibility.

However, a core principle of constitutionalism and the rule of law is that such delegated legislation must remain strictly "within the scope" (委任の範囲内 - inin no hani-nai) of the authority granted by the parent act. If an executive order introduces rules or restrictions not contemplated or authorized by the legislature in the parent act, it can be deemed ultra vires (beyond its powers) and thus invalid. This case is a prime example of the judiciary scrutinizing the content of delegated legislation to ensure it aligns with the delegating statute, rather than merely examining the process or breadth of the act of delegation itself (e.g., a "blanket delegation" challenge).

Key Factors in the Court's Reasoning

Several factors were pivotal in the Supreme Court's decision to invalidate the Cabinet Order provision:

- The Fundamental Purpose of the Parent Act: The Court placed great emphasis on what it identified as the core purpose of Article 80 of the Agricultural Land Act—to protect the right of former owners to recover their land if the original public purpose of its expropriation ceased.

- The "Permanent" Nature of the Legislation: The characterization of the Agricultural Land Act as "permanent legislation" designed to be adaptable to long-term socio-economic changes was crucial. This contrasted with temporary measures like the OFESMA and suggested that Article 80 should be interpreted broadly enough to cover various scenarios where land might no longer be suitable for its original agricultural purpose over time.

- Exclusion of Intended Cases: The Court found that the Cabinet Order, by its narrow definition, "excluded what the Act clearly intended as objects for resale".

Significance of the Ruling

This 1971 Grand Bench decision holds significant importance in Japanese administrative law:

- First Invalidation of Delegated Legislation in an Administrative Case: It is widely recognized as the first instance where the Supreme Court explicitly declared a provision of a Cabinet Order unlawful for exceeding the scope of delegation granted by its parent statute in an administrative law context. (A prior instance of invalidating delegated legislation existed in a criminal case).

- Major Socio-Political Impact: The ruling had immediate and substantial repercussions, particularly concerning unresolved issues from the post-war land reforms. Many former landowners whose land had been purchased by the state but not resold to tenants felt vindicated, and the judgment spurred further legal and political action. The Cabinet Order was amended shortly after the decision, and a special law concerning the resale of state-owned farmland was subsequently enacted to address the situation more comprehensively.

- Reinforcement of Judicial Review: The decision powerfully affirmed the judiciary's role in overseeing executive rulemaking and ensuring that administrative actions remain subservient to the will of the legislature as expressed in statutes.

- Development of Criteria: While the specific criterion used by the Court—whether the order "excludes what the Act clearly intended as objects for resale"—is somewhat abstract and tailored to the case, the judgment implicitly considered several factors that are now generally recognized in analyzing the validity of delegated legislation. These include the text of the delegating provision, the purpose of the delegation, consistency with the overall scheme and objectives of the parent act, and the nature of the rights or interests being restricted by the delegated order. The Court's emphasis on the "permanent" character of the parent law as a guide to the scope of delegation was a particularly notable aspect of its reasoning in this case.

Conclusion

The 1971 Supreme Court judgment in the agricultural land resale case stands as a vital precedent in Japanese law, underscoring the principle that delegated legislative powers are not absolute. Executive bodies, when empowered to make detailed rules, must do so strictly within the boundaries set by the legislature in the parent statute. By invalidating a Cabinet Order provision for overstepping these limits, the Court reinforced the hierarchy of laws, the supremacy of Diet-enacted statutes, and the judiciary's crucial function in safeguarding the rule of law against executive overreach, particularly when fundamental rights such as property are implicated. This case continues to inform the understanding of how legislative intent guides and constrains administrative rulemaking.