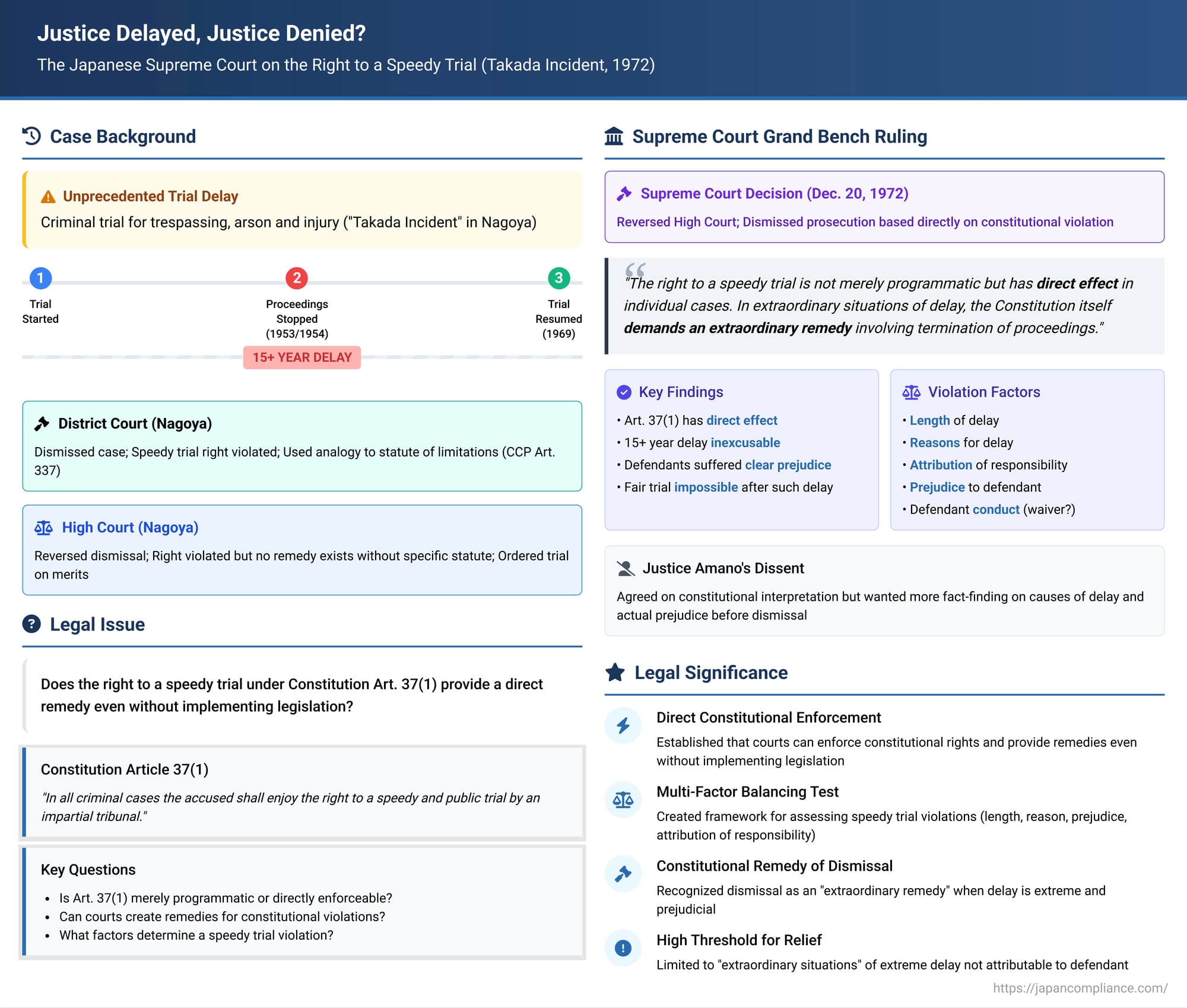

Justice Delayed, Justice Denied? The Japanese Supreme Court on the Right to a Speedy Trial (Takada Incident)

Date of Judgment: December 20, 1972

Introduction

The right to a speedy trial is a fundamental principle recognized in many legal systems, designed to prevent oppressive pre-trial incarceration, minimize anxiety for the accused, and limit the possibility that long delay will impair the ability of an accused to defend himself. In Japan, Article 37, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution explicitly guarantees this right: "In all criminal cases the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial tribunal." But what happens when this right is severely violated due to extraordinary delays in the judicial process? Does the Constitution itself provide a remedy, even in the absence of specific statutory procedures? This profound question was tackled by the Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench, in the landmark 1972 "Takada Incident" decision.

Factual Background: A 15-Year Hiatus in Trial Proceedings

The defendants in this case were indicted for serious offenses, including trespassing, arson, and injury, related to incidents in Nagoya (referred to generally as the "Takada Incident"). The trial proceedings, however, came to a grinding halt.

- For 26 of the defendants, the trial effectively stopped after the 23rd court session on June 18, 1953.

- For the remaining 4 defendants, the last session was the 4th court session on March 4, 1954.

- Astonishingly, no further proceedings took place for over 15 years until the trial was eventually resumed in 1969.

- Trial Court Decision (Dismissal - Menso): The Nagoya District Court, upon resuming the trial, concluded that the defendants' constitutional right to a speedy trial had been severely violated by this extreme delay. Lacking a specific statutory remedy for such a violation, the court decided to apply Article 337, Item 4 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP) analogously – this provision normally mandates dismissal (menso) when the statute of limitations has expired. The trial court thus dismissed the prosecution against the defendants.

- High Court Decision (Reversal and Remand): The prosecutor appealed. The Nagoya High Court, while agreeing that the defendants' right to a speedy trial had indeed been infringed, found that there was no existing legal provision to provide relief for such a violation. It deemed the trial court's analogy to the statute of limitations provision (CCP Art. 337(4)) an impermissible overreach of judicial interpretation. Consequently, the High Court reversed the trial court's dismissal and remanded the case for a substantive trial on the merits.

The defendants appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Ruling: A Constitutional Remedy for Extreme Delay

The Supreme Court Grand Bench reversed the High Court's decision and ultimately upheld the trial court's dismissal of the prosecution, albeit on different grounds. The Court delivered a seminal interpretation of the right to a speedy trial under Article 37(1).

1. Nature of the Right to a Speedy Trial (Art. 37(1)):

* The Court declared that the right to a speedy trial is one of the fundamental human rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

* Crucially, Article 37(1) is not merely a programmatic provision urging legislative and administrative measures. It has direct effect (jiriki jikkōsei) in individual cases.

* If an "extraordinary situation" (ijō na jitai) arises where the trial is significantly delayed, clearly violating the guarantee, and the defendant's right is consequently harmed, then even without specific statutory provisions, the Constitution itself demands an "extraordinary remedy" (hijō kyūsai shudan) involving the termination of the proceedings against the defendant.

2. Rationale for the Right and Harms of Delay:

The Court emphasized the purposes behind the speedy trial guarantee:

* Preventing defendants from being left in limbo regarding their guilt for extended periods, causing tangible and intangible social disadvantages.

* Protecting the integrity of the trial process itself, as excessive delay leads to fading memories (of defendants and witnesses), death of relevant persons, loss of physical evidence, thereby hindering the defendant's ability to mount a defense.

* Ultimately, ensuring the goals of criminal justice – discovering the truth, punishing the guilty while exonerating the innocent, and applying penal law appropriately and swiftly – are not undermined.

3. Remedy for Violation: Termination of Proceedings:

* In cases where extreme delay creates an "extraordinary situation" fundamentally violating the speedy trial right, continuing the trial becomes inappropriate. Discovering the truth becomes exceedingly difficult, a fair trial cannot be expected, and proceeding would only increase the defendant's personal and social disadvantages.

* In such extreme circumstances, the Constitution itself requires the termination of the proceedings (shinri o uchikiru) as an extraordinary remedy.

4. Determining if a Violation Has Occurred:

* Whether a delay violates Article 37(1) is not judged solely by the length of time.

* It requires a comprehensive assessment of various factors:

* The period of delay.

* The causes and reasons for the delay (e.g., complexity of the case vs. inaction by the state).

* Whether the delay was unavoidable.

* The extent to which the defendant's interests protected by the speedy trial right (preventing undue anxiety, ensuring a fair defense) were actually harmed.

* Crucially, if the primary cause of delay lies with the defendant (e.g., flight, refusal to appear, dilatory tactics), the defendant is deemed to have waived their right to a speedy trial, and no violation occurs even with long delays.

5. Application to the Takada Incident:

* The Court acknowledged the 15+ year delay during the prosecution's case-in-chief.

* While the initial interruption was at the defense's request pending the related Ōsu Incident trial, neither the court nor the parties anticipated the Ōsu trial would take so long. The court found no rational reason for the trial court's failure to resume proceedings for such an extended period, especially after the defense indicated willingness to proceed separately around 1964.

* The prosecution also failed to actively push for the trial's resumption.

* While the defendants were passive in seeking resumption, they did not flee or engage in dilatory tactics. The Court explicitly stated that a defendant's failure to actively demand trial progression cannot be interpreted as a waiver of their speedy trial right, at least not before the prosecution rests its case.

* The Court found clear prejudice to the defendants: evidence regarding specific acts remained unexamined; site inspections became impossible due to changed locations; physical evidence was likely lost; memories of witnesses and defendants had faded significantly, making accurate testimony highly doubtful; and challenging the voluntariness of confessions (a key issue) became extremely difficult due to the passage of time.

* Therefore, the Court concluded that by the time the trial court resumed proceedings in 1969, an "extraordinary situation" manifestly violating the speedy trial guarantee of Article 37(1) had already arisen.

6. The Appropriate Remedy:

* While acknowledging the lack of a specific statute for this remedy, the Court held that terminating the proceedings was constitutionally required.

* Given the specific procedural history, the appropriate method for termination was a judgment of dismissal (menso).

* The Court thus found the trial court's conclusion (dismissal) to be correct, even though its reasoning (analogizing to the statute of limitations) was not adopted. It effectively created a "supra-statutory" dismissal based directly on the constitutional violation.

Disposition: The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's judgment (which had ordered a trial on the merits) and dismissed the prosecutor's appeal against the trial court's dismissal judgment, thereby finalizing the termination of the prosecution.

Justice Amano's Dissenting Opinion: Need for Further Fact-Finding

Justice Amano, while agreeing with the majority on the interpretation of Article 37(1) and the potential remedy of dismissal, dissented on the final disposition. He argued that dismissing the case based solely on the existing record and inferences drawn therefrom was premature. He believed that terminating a prosecution is an extreme measure and that before taking such a step, the court should conduct further investigation to definitively establish the primary cause of the delay and the actual extent of prejudice suffered by the defendants, rather than relying on presumptions. He advocated for remanding the case to the High Court for further factual inquiry.

Analysis and Implications: A Landmark Constitutional Remedy

The Takada Incident decision is a landmark in Japanese constitutional and criminal procedure law.

- Direct Effect of Speedy Trial Right: It firmly established that the right to a speedy trial under Article 37(1) is not merely aspirational but a directly enforceable right that can provide a remedy even without specific implementing legislation.

- "Extraordinary Remedy" of Dismissal: It recognized that in exceptional cases of extreme and unjustified delay causing substantial prejudice, the ultimate remedy is the termination of the criminal proceedings, typically through a judgment of dismissal (menso).

- Balancing Test for Violations: It laid out a multi-factor balancing test to determine if a delay violates the right, considering the length of delay, reasons for delay (assigning responsibility), and prejudice to the defendant.

- Rejection of Automatic Waiver: It clarified that a defendant's failure to actively demand trial progress does not automatically constitute a waiver of their speedy trial right, particularly during the prosecution's case.

- Practical Impact: While the threshold for finding a violation requiring dismissal is very high (an "extraordinary situation"), this decision provides a crucial constitutional backstop against egregious delays in the criminal justice system. It emphasizes the responsibility of the state, including the courts and prosecutors, to ensure timely adjudication.

Conclusion

The 1972 Takada Incident judgment stands as a powerful affirmation of the constitutional right to a speedy trial in Japan. It declared that this right is not merely a guiding principle but a directly applicable guarantee that, in extraordinary circumstances of excessive and unjustified delay causing prejudice, mandates the termination of the prosecution as a constitutional remedy. By establishing a framework for assessing such violations and recognizing dismissal (menso) as the appropriate measure in extreme cases, the Supreme Court provided a vital, albeit rarely invoked, safeguard against the potentially devastating consequences of justice delayed.