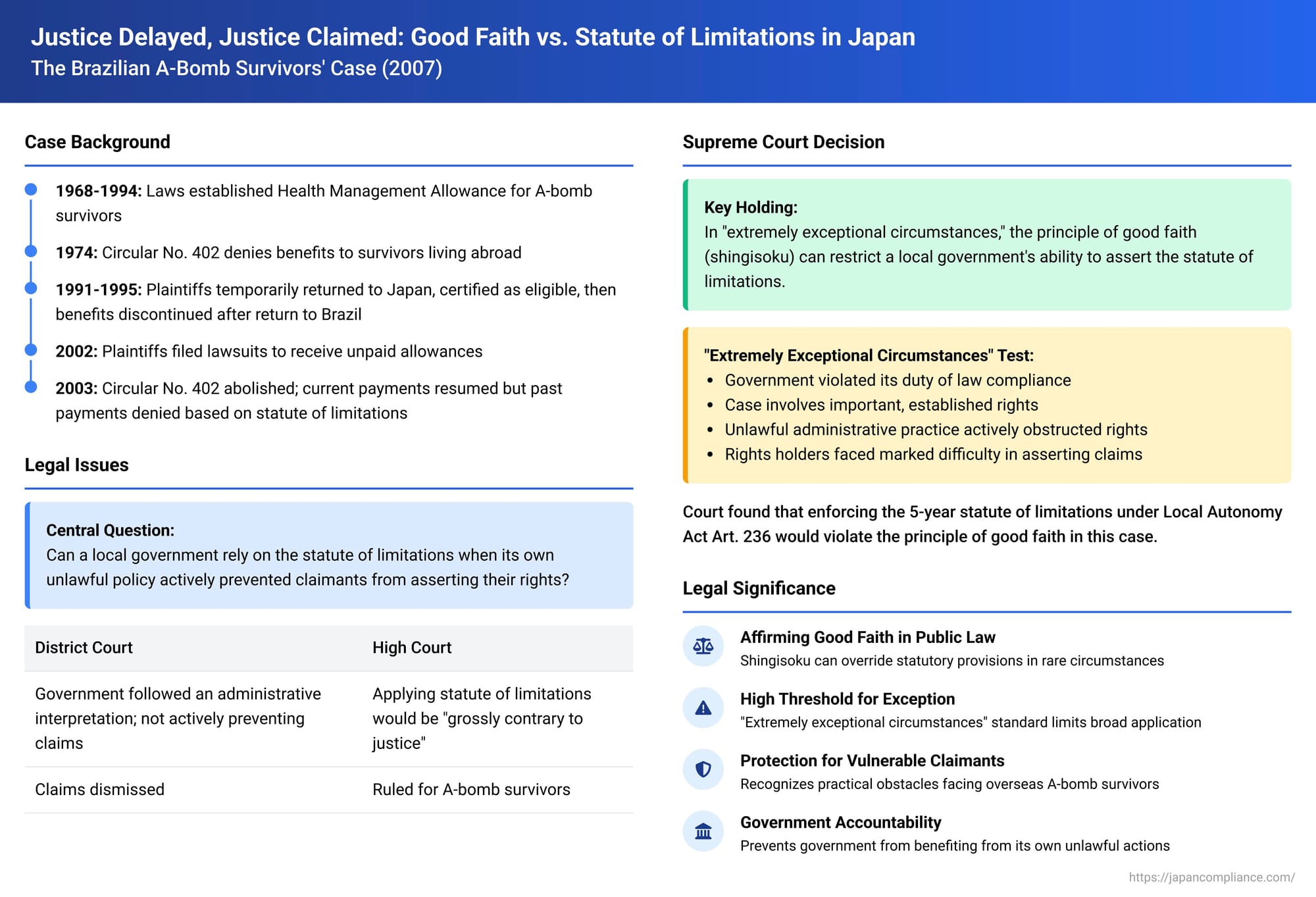

Justice Delayed, Justice Claimed: Good Faith vs. Statute of Limitations in Japan – The Brazilian A-Bomb Survivors' Case

Statutes of limitations are fundamental legal mechanisms designed to ensure legal stability and prevent stale claims. But can a government entity always hide behind such a defense, especially if its own erroneous policies actively prevented citizens from exercising their rights in a timely manner? A compassionate and principled decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on February 6, 2007, addressed this very question, ruling that in "extremely exceptional circumstances," the principle of good faith and trust (shingisoku) can restrict a local government's ability to assert the statute of limitations.

Background: A-Bomb Survivors in Brazil and Disputed Allowances

The plaintiffs in this case (X1, X2, and X3, collectively "X et al.") were Japanese citizens who had survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and subsequently emigrated to Brazil between the 1950s and 1960s.

- Survivor Relief Laws and Allowances: Japan enacted several laws to provide support to A-bomb survivors (hibakusha), recognizing the unique and devastating health consequences of atomic radiation. These laws included the "Act on Special Measures for Atomic Bomb Survivors" (1968, Genbaku Tokubetsu Sochi Hō), which established a Health Management Allowance (kenkō kanri teate) for survivors suffering from specific radiation-related illnesses. These laws were later consolidated into the "Atomic Bomb Survivors' Relief Law" (1994, Hibakusha Engo Hō).

- The Infamous "No. 402 Circular": In 1974, the Director-General of the Public Health Bureau of Japan's Ministry of Health and Welfare issued an administrative directive known as "Circular No. 402" (402-gō Tsūtatsu). This circular stipulated that A-bomb survivors would lose their eligibility for the Health Management Allowance if they emigrated from Japan and took up residence overseas. Crucially, the Supreme Court later acknowledged that this circular was based on an erroneous interpretation of the underlying relief laws, which contained no such disqualification for overseas residence.

- Discontinuation of Payments: Between 1991 and 1995, X et al. temporarily returned to Japan. During these visits, they were formally certified by Y, the Governor of Hiroshima Prefecture, as suffering from illnesses recognized under the survivor relief laws, and they were issued Health Management Allowance certificates for specific periods. However, soon after X et al. returned to their homes in Brazil, Governor Y, acting in accordance with Circular No. 402, discontinued the payment of these allowances. For example, payments to X1 were stopped from July 1995, to X2 from August 1995, and to X3 from July 1994. At the time, the administration of these allowances by prefectural governors was considered an "agency delegated function" (kikan inin jimu), meaning the governor was acting as an organ of the national government under the direction of the relevant minister.

- Lawsuits and Subsequent Policy Change: Between July and December 2002, X et al. filed lawsuits in Japan seeking the payment of their unpaid Health Management Allowances. Subsequently, on March 1, 2003, Circular No. 402 was formally abolished. Regulations were amended to explicitly confirm that A-bomb survivors residing outside Japan were indeed eligible for the allowance. Following this change, Governor Y began to pay the current and future allowances to X et al. However, Y refused to provide back-payments for those portions of the unpaid allowances that were deemed to have become time-barred – specifically, where the monthly claim had passed the five-year statute of limitations prescribed by Article 236 of the Local Autonomy Act by the time the lawsuits were initiated. This refusal led to the legal battle that reached the Supreme Court.

Lower Court Rulings: A Clash of Perspectives

The lower courts presented differing views on whether the statute of limitations should apply:

- Hiroshima District Court (First Instance): The District Court dismissed the claims of X et al. for the time-barred amounts. It reasoned that Governor Y had merely been following an administrative interpretation of the law (i.e., Circular No. 402) and had not actively or illegally prevented X et al. from taking legal action sooner. The court expressed concern that generally allowing the statute of limitations to be overridden simply because a court later found an administrative interpretation to be incorrect would undermine the purpose of statutes of limitations, which is to ensure legal stability through the timely resolution of claims.

- Hiroshima High Court (Second Instance): The High Court reversed the District Court's decision, ruling in favor of X et al.. It found that Circular No. 402 was based on an incorrect and unlawful interpretation of the survivor relief laws and had, for many years, unjustly denied A-bomb survivors essential rights that were established out of state compensatory considerations. The High Court concluded that applying the statute of limitations under Article 236 of the Local Autonomy Act in this specific situation would effectively close the door on recovering these wrongfully denied benefits and would be "grossly contrary to justice" (ichijirushiku seigi ni hansuru). It held that the plaintiffs' inability to exercise their rights was a direct result of Governor Y's refusal to pay based on the illegal circular, a situation tantamount to Y having actively prevented the exercise of their rights.

Governor Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Good Faith Overrides Statute of Limitations in Exceptional Cases

The Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court, in its judgment of February 6, 2007, dismissed Governor Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision in favor of the A-bomb survivors.

Local Government Statute of Limitations (Local Autonomy Act Art. 236)

- The Court first addressed Article 236, Paragraph 2 of the Local Autonomy Act. This provision states that, unlike typical civil claims where the debtor must "invoke" (en'yō) the statute of limitations for it to take effect (Civil Code Art. 145), monetary claims against local public entities automatically extinguish upon the expiration of the five-year period, unless other laws provide a special stipulation.

- The rationale for this automatic effect, the Court explained, lies in considerations of administrative convenience for the local government in processing such claims uniformly and appropriately according to law, and in upholding the principle of equal treatment of residents (as referenced in Local Autonomy Act Art. 10, Para. 2). Therefore, the private law system of requiring an "invocation of prescription" (jikō en'yō no seido) is deemed unnecessary for these public law claims.

- Consequently, the Court stated that any instances where a local government's assertion of the statute of limitations (or reliance on its automatic effect) would be deemed contrary to the principle of good faith (shingisoku) and thus impermissible should be "extremely limited" (kiwamete gentei sareru mono).

The "Extremely Exceptional Circumstances" Exception

Despite this high threshold, the Supreme Court carved out a narrow but crucial exception based on the fundamental obligations of local governments:

- Local public entities have a primary duty to comply with laws and ordinances in their administrative actions (as stipulated in Local Autonomy Act Art. 2, Para. 16) and to perform their obligations faithfully and in good faith.

- The Court found that the present case involved "extremely exceptional circumstances" (kiwamete reigaiteki na baai) that justified restricting the governor's reliance on the statute of limitations. These circumstances arose because:

- The local government (Governor Y, acting in this capacity), contrary to its fundamental duty of law compliance, was dealing with an important, concretely established right of citizens – the Health Management Allowance, a critical benefit for A-bomb survivors.

- The governor did so by unilaterally and uniformly applying an unlawful administrative practice (namely, adhering to the No. 402 Circular and treating overseas survivors as having forfeited their rights) that actively obstructed the exercise of these established rights.

- This unlawful practice made it markedly difficult (ichijirushiku konnan) for the survivors, residing overseas, to exercise their rights, which directly resulted in these rights becoming time-barred.

Why the Exception Applied in This Specific Case

- The Supreme Court reasoned that in such "extremely exceptional circumstances," the usual justifications for allowing the local government the "administrative convenience" of automatic prescription (without needing to invoke it) are fundamentally undermined.

- Furthermore, disallowing the local government's reliance on the statute of limitations in this specific context would not violate the principle of equal treatment of citizens and would not cause any particular hindrance to administrative processing.

- The Court emphasized the practical reality faced by the overseas survivors. While an administrative circular is not directly legally binding on citizens, it represents an interpretation of law by higher administrative organs and creates a strong presumption among citizens that it has a proper legal basis. Therefore, expecting individual A-bomb survivors residing abroad to challenge such a clear and authoritative directive through legal action to claim their allowances was deemed extremely difficult and unrealistic. The Court highlighted that any administrative body issuing a circular that effectively nullifies important, established rights should do so only after considerable careful examination and consideration, which was evidently lacking in the case of Circular No. 402, particularly as it applied to survivors who had already left Japan and would find it hard to assert their rights.

- The Court equated the governor's actions—implementing an unlawful circular that made rights assertion exceptionally difficult—to the government itself being responsible for the claimants' failure to exercise their rights within the normal timeframe.

Conclusion on Shingisoku

Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded that Governor Y's assertion of the statute of limitations under Local Autonomy Act Art. 236 to deny the unpaid Health Management Allowances to X et al. was, in this instance, impermissible as a violation of the principle of good faith (shingisoku). The Court found no special circumstances that would have made it reasonable to expect these particular survivors to file lawsuits despite the existence and application of the No. 402 Circular.

A supplementary opinion by Justice Fujita Tokiyasu agreed with the majority's conclusion but offered an alternative theoretical path. He suggested that such "extremely exceptional circumstances" could be viewed as analogous to "special provisions of law" (an exception already contemplated in the proviso of Local Autonomy Act Art. 236, Para. 2), which would then necessitate an "invocation" of the statute of limitations by the local government. This act of invocation could, in turn, be challenged as a violation of the principle of good faith.

Analysis and Implications

This 2007 Supreme Court decision carries significant weight in Japanese public and administrative law:

- Vindication of Shingisoku in Public Law: The ruling powerfully affirms that the principle of good faith and trust (shingisoku) is not merely a private law concept but a fundamental legal principle that can, in appropriate (albeit rare) circumstances, limit a local government's ability to rely on otherwise applicable statutory provisions, such as those concerning the statute of limitations.

- A High Bar for "Exceptional Circumstances": The Court repeatedly emphasized the "extremely limited" and "extremely exceptional" nature of the circumstances under which this principle would override the standard operation of the statute of limitations for claims against local governments. It is not a wholesale invitation to disregard limitation periods whenever a government error is alleged. The government's actions must have been not just erroneous but must have actively and unlawfully obstructed the exercise of an important, already established right, making its assertion markedly difficult.

- Scrutiny of Unlawful Administrative Directives (Tsūtatsu): The judgment demonstrates the judiciary's willingness to look beyond the formal non-binding nature of administrative circulars (tsūtatsu) on citizens and to assess their real-world impact. When such directives form the basis of unlawful administrative practices that effectively strip citizens of their vested rights, this can trigger the application of equitable principles like shingisoku to prevent the government from benefiting from its own unlawful conduct by later pleading the statute of limitations. The commentary notes the significance of applying shingisoku to the consequences of issuing a tsūtatsu, which is an abstract, internal administrative act, when it leads to such concrete deprivations.

- Protection for Vulnerable Claimants: The specific context of the plaintiffs – elderly A-bomb survivors residing overseas – likely played a role in the Court's assessment of the "extreme difficulty" they faced in asserting their rights against a clear (though illegal) governmental directive. This highlights a sensitivity to situations where there is a significant power imbalance or practical obstacles to accessing justice. The commentary suggests that this "special exceptionality" might be linked to the vulnerable status of the claimants and the fundamental nature of the rights involved (health and welfare benefits for A-bomb survivors).

- Emphasis on Local Governments' Duty of Law Compliance: The ruling implicitly underscores that local governments, even when implementing national policies or directives (as was the case under the former "agency delegated functions" system), bear a fundamental responsibility to ensure their actions comply with the law. Blind adherence to an unlawful directive from a higher authority that results in the infringement of citizens' rights may not be a complete shield against legal consequences, including the restriction of procedural defenses. The commentary suggests the ruling could be interpreted as a call for local governments to exercise their own capacity for legal interpretation rather than uncritically following national directives.

- Ongoing Theoretical Discussion: The legal commentary points to an ongoing academic discussion regarding the precise theoretical framework for disallowing a statute of limitations defense when the relevant statute (like Local Autonomy Act Art. 236) does not require a formal "invocation" by the debtor. While the Supreme Court reached its conclusion based on the imperative to avoid an unjust outcome in this specific, egregious situation, the exact doctrinal mechanics remain a subject of legal analysis.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2007 decision in the Brazilian A-Bomb Survivors' case is a profound statement on the paramountcy of justice and good faith, even in the face of seemingly absolute statutory provisions like the automatic effect of the statute of limitations for claims against local governments. It clarifies that while such provisions serve important public purposes, they cannot be used by a government entity to benefit from its own unlawful actions when those actions have actively and systematically prevented vulnerable citizens from exercising their important, established rights. This ruling champions the idea that legal technicalities must sometimes yield to fundamental principles of fairness, particularly when the state itself has created the conditions that impede access to justice.