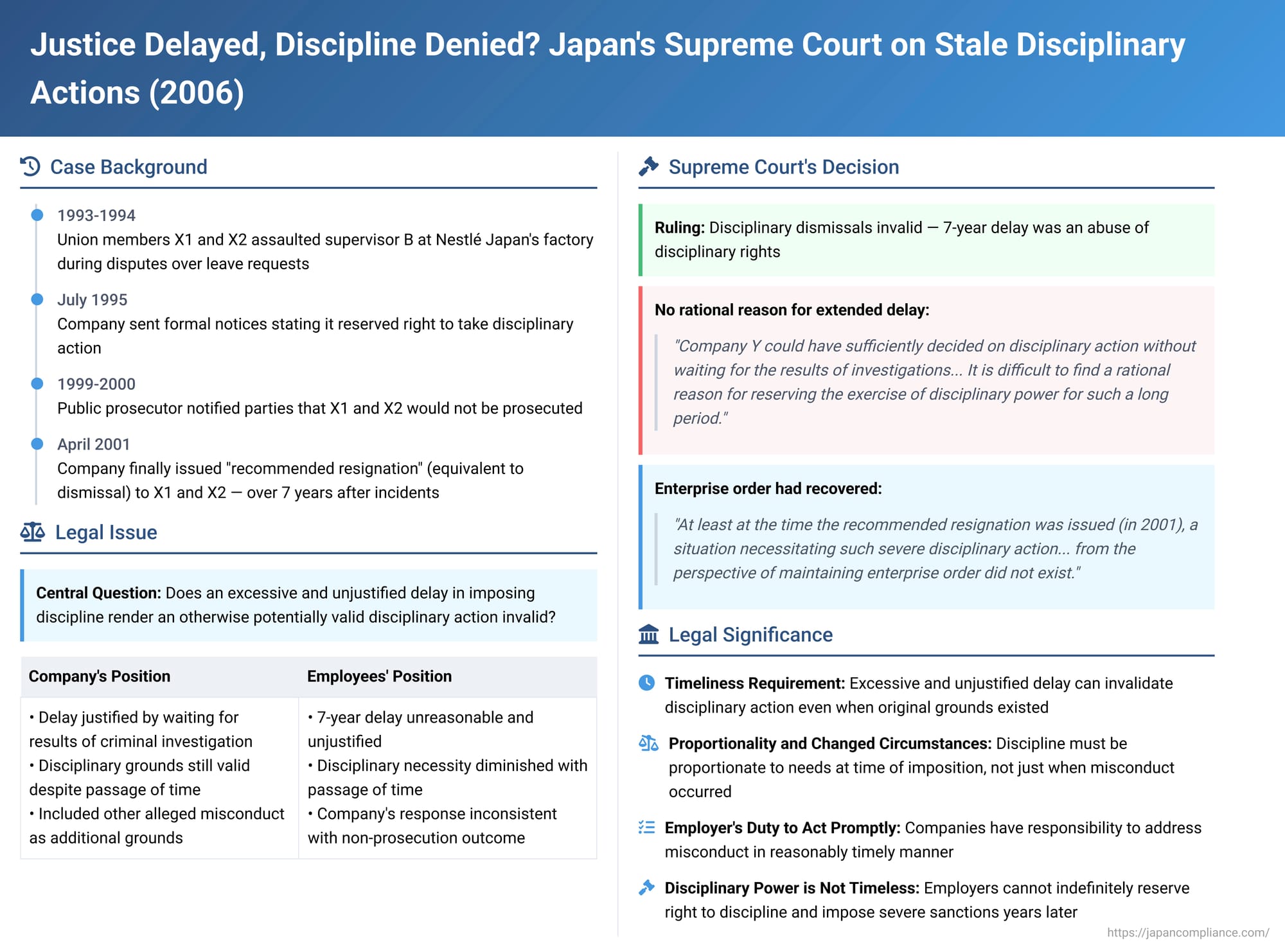

Justice Delayed, Discipline Denied? Japan's Supreme Court on Stale Disciplinary Actions (October 6, 2006)

On October 6, 2006, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case often referred to as the "Nestlé Japan Case". This ruling addressed the validity of severe disciplinary actions taken against employees several years after the primary instances of misconduct had occurred. The Court's decision emphasized that even if grounds for discipline initially exist, an excessive and unjustified delay in imposing sanctions can render them an abuse of the employer's disciplinary rights, particularly if the passage of time has diminished the necessity of such measures for maintaining enterprise order.

Workplace Turmoil: Assaults and Allegations

The plaintiffs, X1 and X2, were employees of Defendant Company Y, a food manufacturing company, stationed at its K factory. They were prominent members of the K factory branch of the A Labor Union, known for its more adversarial stance towards Company Y compared to other unions at the facility.

The core events leading to the disciplinary actions unfolded several years prior:

- Background Dispute (June 1993): The catalyst for the initial conflict was a dispute over paid annual leave. X2 had taken a day off due to illness and subsequently requested that this absence be converted into paid annual leave. This request was denied by X2's supervisor, B, on the grounds that it was submitted after the company's deadline for such conversions. The A Labor Union's K branch perceived this denial as an act of hostility towards the union. In response, union members, including X1 and X2, began a series of protest actions, such as verbally confronting managers (including supervisor B) in the workplace with demands like "Approve the paid leave!"

- The "Incidents" – Assaults on a Supervisor: Against this backdrop of heightened tension, three specific incidents of assault against supervisor B occurred:

- October 25, 1993 (Incident 1): Inside the K factory premises, X1 accosted supervisor B, shouting aggressively, grabbing B's necktie and collar, and physically pushing B against a wall. Plaintiff X2 was present and reportedly supported X1 in this confrontation.

- October 26, 1993 (Incident 2): X2 and several other members of the A Labor Union surrounded supervisor B, effectively immobilizing him. Plaintiff X1 then assaulted B by kicking his knee. Following this, X1 grabbed B's collar, applying pressure to his neck, and twisted B's right little finger. Plaintiff X2 also participated by grabbing B's work attire.

- February 10, 1994 (Incident 3, involving X2 only): After another leave-related dispute where supervisor B refused to convert X2's sick leave (February 7-8) into paid annual leave, X2 reacted with further aggression. On February 10, while B was working in an office, X2 approached B, put an arm around B's neck, and punched B in the abdomen.

- Company Y's Initial Steps and Prolonged Delay:

- Company Y initiated an investigation into these incidents. Around July 1995, it sent formal notices to X1, X2, and another union member, C (who was involved in Incident 2). These notices detailed the incidents, urged the employees to engage in serious self-reflection, and stated that the company reserved its right to take disciplinary action, including other measures of responsibility.

- However, supervisor B had filed police reports concerning Incident 2 and Incident 3. Consequently, Company Y decided to postpone any internal disciplinary action against the employees until the outcome of these official criminal investigations was known.

- Non-Prosecution and Further Deferral of Action:

- It was not until late 1999 and early 2000 (between December 1999 and March 2000) that the relevant parties, including Company Y, were formally notified by the public prosecutor's office that X1, X2, and C would not be prosecuted in connection with the incidents.

- Following this notification, Company Y began internal deliberations regarding disciplinary measures. In May 2000, the K factory manager approached employee C (involved in Incident 2), informed him that disciplinary action was being considered by headquarters, and suggested that C might wish to resign voluntarily. C initially submitted a resignation letter but retracted it the following day. C then initiated legal proceedings (a provisional disposition application to preserve employment status and a full lawsuit) to contest the validity of the (retracted) resignation. When the court issued a temporary order compelling Company Y to continue paying C's wages, Company Y decided to further delay taking disciplinary action against X1 and X2.

- In March 2001, the lawsuit brought by C was dismissed, with the court largely accepting Company Y's arguments in that separate matter.

- The Disciplinary Action (April 2001):

- Only after the resolution of C's case did Company Y proceed with disciplinary action against X1 and X2. In April 2001 – more than seven years after the primary assaults in 1993 and 1994 – Company Y issued a "recommended resignation" (諭旨退職処分 - yushi taishoku shobun) to both X1 and X2.

- The grounds cited for this severe disciplinary measure included:

- The assaults committed against supervisor B during the Incidents of October 1993, October 1993, and February 1994.

- Other alleged acts of misconduct by X1 and X2 occurring over an extended period, such as unauthorized departures from the workplace and the use of abusive language.

- A more recent specific incident on October 12, 1999 (the "Work Obstruction Incident"), where X1 and X2 were accused of using abusive language towards supervisor B while B was attending to factory visitors, thereby obstructing B's duties.

- Under Company Y's work rules, a "recommended resignation" stipulated that if the employee submitted a formal resignation letter by a specified deadline, their departure would be treated as a voluntary resignation (for personal reasons), allowing them to receive full severance pay. If no resignation letter was submitted by the deadline, the action would automatically convert into a disciplinary dismissal.

- Neither X1 nor X2 submitted resignation letters. As a result, they were formally subjected to disciplinary dismissal by Company Y, effective April 26, 2001.

X1 and X2 then filed this lawsuit to challenge the validity of these disciplinary dismissals. The Mito District Court (Ryugasaki Branch) initially ruled in their favor, finding the dismissals invalid. However, the Tokyo High Court reversed this decision, deeming the disciplinary dismissals to be valid. X1 and X2 subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Dismissals Invalidated as Abuse of Rights

The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision and, ruling directly on the merits, declared the disciplinary dismissals of X1 and X2 invalid.

I. The General Principle: Limits on Disciplinary Power

The Court began by affirming the standard legal framework for assessing disciplinary actions: "The exercise of an employer's disciplinary power is carried out as an employer's authority based on the employment contract relationship from the perspective of maintaining enterprise order. However, even if facts exist that fall under a disciplinary cause stipulated in the work rules, if, under the specific circumstances, it objectively lacks a rational reason and cannot be approved as socially appropriate, it is reasonable to interpret it as an abuse of rights and thus invalid". This is a well-established doctrine in Japanese labor law, ensuring that disciplinary power is not wielded arbitrarily.

II. Unreasonableness of the Prolonged Delay Regarding the 1993-1994 Incidents

The Supreme Court found the seven-year delay in imposing discipline for the primary assaults to be a critical flaw:

- Company Y had asserted that it delayed its internal disciplinary process to await the outcome of the police investigations initiated by supervisor B regarding Incidents 2 and 3.

- The Court rejected this justification: "However, the Incidents in question were assaults on a manager that occurred at the workplace during working hours, and there were witnesses other than the victim manager. Therefore, it is considered that Company Y could have sufficiently decided on disciplinary action against X1 and X2 without waiting for the results of the said investigations. It is difficult to find a rational reason in this case for reserving the exercise of disciplinary power for such a long period".

- The Court also pointed to an inconsistency in Company Y's approach: "Moreover, when an employer decides to consider disciplinary action for an employee's misconduct after waiting for the results of an investigation, and if that investigation results in non-prosecution, it is considered normal practice for the employer also not to impose a severe disciplinary action such as disciplinary dismissal. Despite the said investigation resulting in non-prosecution, for Company Y to impose on X1 and X2 a severe disciplinary action like the recommended resignation, which is substantially equivalent to disciplinary dismissal, cannot but be said to lack consistency in its response".

III. Assessment of Other Cited Disciplinary Grounds

The Court also considered the other grounds Company Y had cited for the 2001 disciplinary action:

- Most of these other alleged acts of misconduct (apart from the October 1999 Work Obstruction Incident) had also occurred many years prior to the 2001 disciplinary action.

- Regarding the October 1999 Work Obstruction Incident (where X1 and X2 allegedly shouted abuse at supervisor B while B was with factory visitors), the Court stated: "even if such facts exist, that single act itself can hardly be said to be conduct deserving of a recommended resignation. Moreover, more than 18 months had passed from when these alleged acts of abusive language and work obstruction occurred until the recommended resignation was issued".

- Taking these factors into account, the Court inferred: "Considering these points, it can be inferred that workplace order gradually recovered with the passage of time after the Incidents (of 1993-1994). At least at the time the recommended resignation was issued (in 2001), a situation necessitating such severe disciplinary action as disciplinary dismissal or recommended resignation against X1 and X2 from the perspective of maintaining enterprise order did not exist".

IV. Conclusion: An Abuse of Disciplinary Rights

Based on this comprehensive analysis, the Supreme Court concluded: "Considering all these points, the recommended resignation処分, issued more than 7 years after the Incidents, even assuming the existence of facts as asserted by Company Y regarding disciplinary dismissal grounds other than the Incidents (grounds on which the High Court did not make specific factual findings), must be said to lack an objectively rational reason necessitating such severe disciplinary action from the perspective of maintaining enterprise order at the time of the disposition, and cannot be approved as socially appropriate. Therefore, the recommended resignation should be deemed an abuse of rights and thus invalid, meaning the disciplinary dismissals based on it are also ineffective".

Key Legal Principles and Implications

This judgment from the Supreme Court provides crucial guidance on the exercise of disciplinary power, particularly concerning delays.

- Timeliness as a Factor in Reasonableness: While not establishing a strict statute of limitations for disciplinary actions, the ruling clearly indicates that an excessive and unjustified delay in imposing discipline can render an otherwise potentially valid sanction unreasonable and an abuse of rights. The key consideration is whether, at the time the discipline is finally imposed, there remains a genuine and objective need for such a measure to maintain or restore enterprise order.

- Employer's Duty to Act with Reasonable Promptness: The decision implies that employers generally have a responsibility to address employee misconduct in a reasonably timely manner. The argument that the company was waiting for the outcome of criminal investigations was found unconvincing in this case, given that the incidents were internal workplace matters with available witnesses, allowing the company to conduct its own investigation and make a determination much sooner.

- Proportionality and Changed Circumstances: The passage of time can significantly alter the context. Misconduct that might have warranted severe discipline shortly after it occurred may not justify the same level of sanction years later, especially if workplace order has since been restored and the employee has continued to work without further serious incident. The discipline must be proportionate to the need for maintaining order at the time the discipline is imposed.

- Consistency in Employer Response: The Court highlighted the inconsistency of imposing a very severe penalty (tantamount to dismissal) after criminal investigations resulted in non-prosecution, suggesting that employers should generally adopt a more lenient approach in such circumstances if they choose to wait for external proceedings.

- Due Process Considerations: Although not explicitly framed as a due process violation by the Supreme Court in this judgment, the commentary notes that academic discussion often links the issue of delayed discipline to due process principles. A long delay can impair an employee's ability to defend themselves effectively due to the potential for evidence to be lost or memories to fade.

Conclusion: A Check on Delayed Disciplinary Power

The Supreme Court's decision in the Food Manufacturer Y (Nestlé Japan) case serves as an important check on the employer's power to impose disciplinary sanctions long after the alleged misconduct has occurred. It underscores that the right to discipline is not timeless and must be exercised in a manner that is objectively rational and socially appropriate given all circumstances, including the timing of the action. Employers cannot indefinitely reserve their right to discipline and then impose severe sanctions years later without a compelling justification for the delay and a clear, present need for such measures to uphold enterprise order. This ruling reinforces the principle that disciplinary actions must be fundamentally fair and proportionate, considering not only the original misconduct but also the intervening passage of time and its impact on the workplace environment.