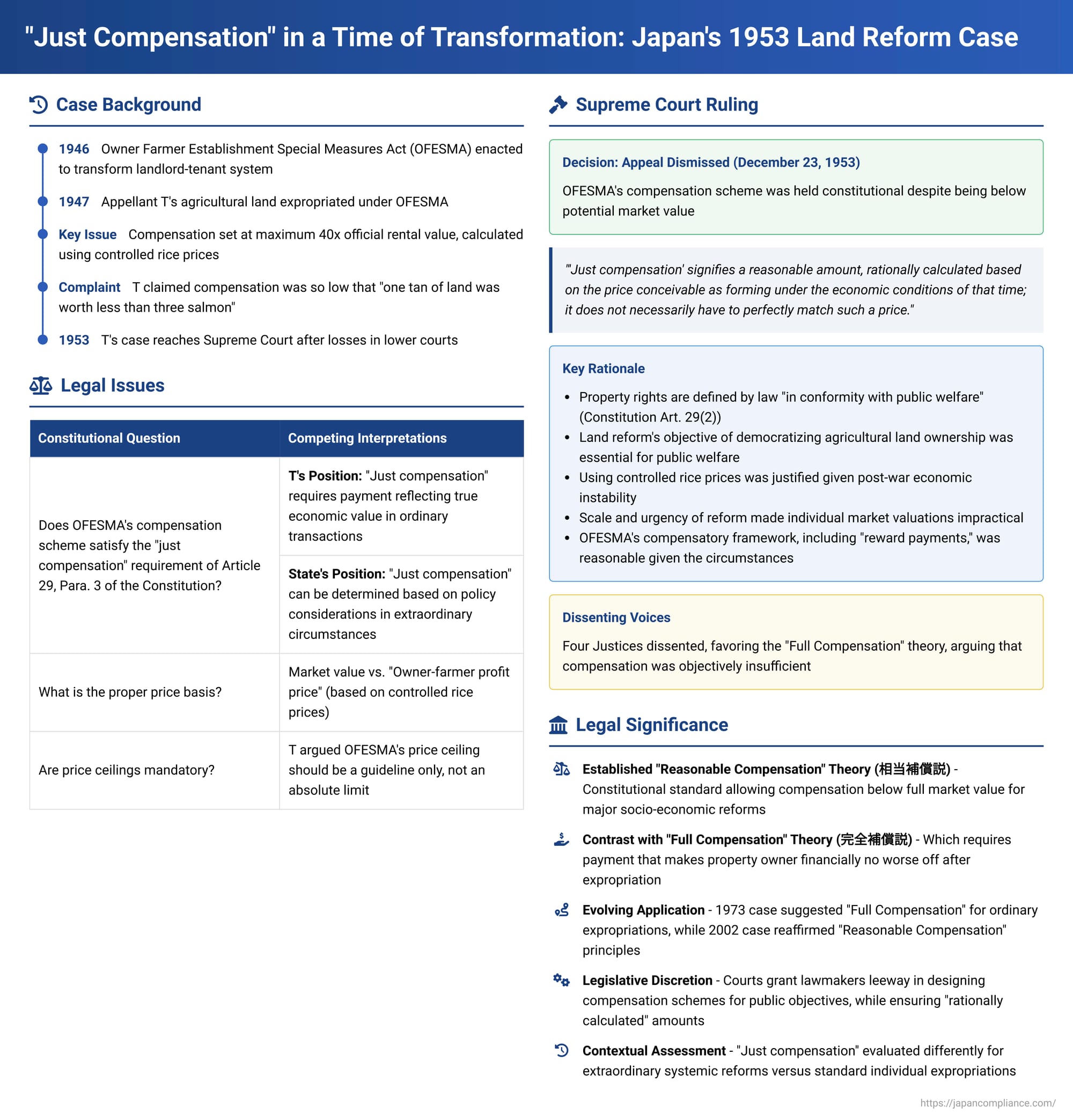

"Just Compensation" in a Time of Transformation: Japan's 1953 Land Reform Case

Date of Judgment: December 23, 1953

Case: Appeal Against Farmland Expropriation

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Introduction: Seeds of Change in Post-War Japan

The years following World War II were a period of profound socio-economic restructuring in Japan. Among the most sweeping reforms was the extensive land reform program, designed to dismantle the traditional landlord-tenant system, reduce rural inequality, and foster a more democratic agricultural base by creating a large class of owner-farmers. This monumental undertaking involved the compulsory purchase of vast tracts of agricultural land by the State from landlords for resale to tenant farmers. While the objectives were widely seen as crucial for Japan's democratization and economic stability, the process inevitably raised fundamental legal questions, particularly concerning the constitutional guarantee of "just compensation" for private property taken for public use, as enshrined in Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the post-war Constitution.

A pivotal moment in the interpretation of this guarantee came on December 23, 1953, when the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered its judgment in a case challenging the adequacy of compensation provided under the land reform laws. This decision not only addressed the immediate grievances of an expropriated landowner but also established foundational principles for understanding "just compensation" that would resonate through Japanese jurisprudence for decades to come.

The Owner Farmer Establishment Special Measures Act (OFESMA): Legislating a New Rural Order

The legislative centerpiece of the land reform was the Owner Farmer Establishment Special Measures Act of 1946 (自作農創設特別措置法, hereinafter "OFESMA"). This Act empowered the government to compulsorily acquire agricultural land from absentee landlords and from resident landlords whose holdings exceeded certain limits. The acquired land was then to be sold to tenant farmers, transforming them into independent proprietors.

A critical aspect of OFESMA was its mechanism for determining the price paid to landowners. Article 6, Paragraph 3 of the Act stipulated that the purchase price for rice paddies, for instance, could not exceed 40 times their official rental value. This valuation was not based on prevailing free market prices, which were difficult to ascertain in the turbulent post-war economy and were, in any case, considered inflated due to speculative pressures and the restrictive nature of the old land tenure system. Instead, the price was derived from a formula based on the "owner-farmer profit price" (自作収益価格). This price was calculated by taking the estimated net yield of the land (based on official rice prices, which were themselves controlled to ensure food security) and capitalizing it at the then-current yield of government bonds. The aim was to set a price that would be economically viable for the new owner-farmers who would cultivate the land. In addition to this acquisition price, OFESMA also provided for a "reward payment" (報奨金) to landowners, calculated based on the area of land expropriated.

The Plight of T: A Constitutional Challenge to "Confiscatory" Prices

The appellant in the 1953 Supreme Court case, an individual landowner whom we will refer to as T, had his agricultural land expropriated by the State in 1947 under the provisions of OFESMA. He was compensated according to the official price ceiling. T contended that this compensation was grossly inadequate and amounted to a violation of his constitutional right to "just compensation" under Article 29, Paragraph 3.

T's arguments before the courts were multifaceted:

- Intrinsic Economic Value vs. Artificial Prices: He argued that "just compensation" should reflect the true economic value of the property as recognized in ordinary economic transactions. Basing the valuation on an arbitrarily fixed official rice price, which was part of a broader system of wartime and post-war economic controls, was impermissible.

- Failure to Account for Hyperinflation: T highlighted the dramatic depreciation in the value of currency and the soaring inflation that characterized the post-war Japanese economy. The compensation formula, he claimed, failed to take these severe economic shifts into account. He vividly illustrated his point by asserting that the official purchase price for one tan (a traditional unit of land area, approximately 0.245 acres) of rice paddy was so low that it was less than the market price of three salmon. This, he argued, rendered the expropriation tantamount to confiscation without any meaningful payment.

- OFESMA as a Guideline, Not an Absolute Ceiling: T proposed that Article 6, Paragraph 3 of OFESMA, which set the maximum price, should be interpreted merely as a guideline or a standard. The actual compensation, he urged, should be determined fairly by considering the general economic conditions prevailing at the precise time of the expropriation.

Having his claims rejected by both the court of first instance (Yamagata District Court) and the appellate court (Sendai High Court), T brought his case to the Supreme Court, seeking an increase in the compensation amount based on his constitutional challenge.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Upholding the Reform Measures

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, in its majority opinion, dismissed T's appeal, thereby upholding the constitutionality of the compensation scheme under OFESMA. The Court's reasoning was extensive and laid the groundwork for the "Reasonable Compensation" theory in Japanese constitutional law.

1. Defining "Just Compensation": The "Reasonable Amount" Standard

The Court began by interpreting the crucial phrase "just compensation" in Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution. It held that "just compensation" signifies:

"a reasonable amount, rationally calculated based on the price conceivable as forming under the economic conditions of that time; it does not necessarily have to perfectly match such a price."

The Court reasoned that this interpretation was consistent with Article 29, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution, which states that "Property rights shall be defined by law, in conformity with the public welfare." This provision, the Court implied, means that property rights are not absolute and can be subject to limitations and regulations necessary for promoting the public good. Consequently, the State can impose certain restrictions on the use, profitability, or disposition of property, and even on the determination of its value, meaning that free market transaction prices might not always be the mandatory standard for compensation.

2. Justification of OFESMA's Pricing Methodology

The Court then scrutinized the specific pricing standards set forth in OFESMA Article 6, Paragraph 3. It found them to be constitutionally permissible for several reasons:

- Purpose of the Law: The Court emphasized that OFESMA's objective was to fundamentally reform Japan's agricultural structure by establishing a broad class of owner-farmers. This was seen as essential for stabilizing the lives of cultivators and enhancing agricultural productivity – goals deeply aligned with the public welfare. Using the "owner-farmer profit price" as a basis, rather than a "landlord profit price," was deemed a natural consequence of these policy aims.

- Official Rice Price: The valuation's reliance on the official (controlled) price of rice was acknowledged. However, the Court viewed this price control as a necessary legal measure at the time to ensure the national food supply and maintain overall economic stability in a period of crisis. Given these vital public interests, using the official rice price as a component in the land valuation formula was considered justified and reasonable for that period.

- Objectivity and Practicality: The Court noted that the items and figures used in the compensation calculation were based on objective and average standards. It stressed the immense scale and urgency of the land reform program, which aimed to rapidly create owner-farmers across the entire nation. In such a context, the Court stated, it would be impermissible and impractical to determine compensation for each individual parcel of land based on the fluctuating prices that might be achieved in free market transactions, which were themselves constrained and unreliable.

- OFESMA Art. 6(3) as an Upper Limit: The Supreme Court rejected T's argument that the price stipulated in OFESMA was merely a guideline. Instead, it interpreted the provision as establishing a legitimate upper limit for compensation. The amount was deemed sufficient if it fell within this statutory standard.

3. Controlled Prices and Public Welfare

Addressing T's complaint about the disparity between the official compensation and other market prices (like that of salmon), the Court observed that controlled prices are, by their nature, established for the sake of public welfare. Therefore, they do not always align perfectly with prices that might reflect profitability under normal economic conditions, and certainly not with prices formed in unrestricted free markets. The fact that the OFESMA compensation did not precisely track other prevailing market prices did not, in itself, render the compensation "unjust."

Based on this comprehensive reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that the compensation provided to T under OFESMA, despite its perceived inadequacy by the appellant, did indeed meet the constitutional requirement of "just compensation."

It is noteworthy that the judgment included a supplementary opinion from one Justice and dissenting opinions from four other Justices, indicating a division within the Court on this critical issue. The dissenting opinions generally leaned towards a "full compensation" model, arguing that the compensation offered was objectively insufficient.

Unpacking the Doctrine: "Reasonable Compensation" vs. "Full Compensation"

The 1953 Supreme Court decision is widely regarded as establishing the "Reasonable Compensation" theory (相当補償説 - sōtō hoshō setsu) as the prevailing interpretation of "just compensation" in Japan, particularly in the context of large-scale socio-economic reforms. This theory stands in contrast to the "Full Compensation" theory (完全補償説 - kanzen hoshō setsu).

- Full Compensation Theory: This theory posits that "just compensation" requires payment of the full objective market value of the expropriated property at the time of taking. The aim is to ensure that the property owner is financially no worse off after the expropriation than before. The dissenting opinions in the 1953 case largely reflected this viewpoint, arguing that the compensation for T's land, being far below any realistic market valuation, was unconstitutional.

- Reasonable Compensation Theory: As articulated by the 1953 majority, this theory allows for compensation that is "rationally calculated" and "reasonable" under the prevailing economic circumstances and in light of the public purpose, even if it falls short of the full market price. The emphasis is on a fair balance between public welfare and individual property rights, acknowledging that in certain extraordinary circumstances, such as a nationwide land reform program essential for democratic and economic rebuilding, the state may have more leeway in determining compensation levels.

The Supreme Court's adoption of the Reasonable Compensation theory in this landmark case was heavily influenced by the unique context:

- Public Welfare (Constitution Art. 29(2)): The Court leaned on the principle that property rights are not absolute and can be shaped by law to serve the public welfare. The land reform was deemed a paramount public welfare objective.

- Systemic Reform: The OFESMA was not an isolated act of expropriation but a comprehensive, systemic overhaul of the nation's agricultural property structure. Such reforms, it was argued, might necessitate different compensation standards than individual takings for specific public works.

- Impracticality of Market Valuation: Given the sheer scale of the land transfers and the distorted post-war economic conditions, determining and paying full "market value" for every parcel of land was seen as practically unfeasible and potentially detrimental to the reform's success.

While legally vindicated, the decision undoubtedly imposed significant financial hardship on landowners like T, whose poignant "three salmon" comparison underscored the deep chasm between the official compensation and the perceived economic reality of the time.

The Enduring Legacy and Evolution of "Just Compensation" in Japan

The 1953 Supreme Court decision cast a long shadow over Japanese compensation jurisprudence. For many years, it was often viewed as a ruling heavily tied to the exceptional circumstances of post-war reconstruction and land reform.

A significant development occurred in 1973 when the Supreme Court, in a case concerning land expropriation for a public road project (Showa 48.10.18), stated that compensation under the Land Expropriation Act should be "full compensation, that is, compensation that makes the property value of the expropriated person equal before and after the expropriation." This 1973 ruling was widely interpreted by legal scholars as endorsing the Full Compensation theory for ordinary expropriations under the Land Expropriation Act, and some argued it even reflected a constitutional preference for full compensation in such standard cases.

This created a jurisprudential landscape where the 1953 "Reasonable Compensation" standard seemed to apply to extraordinary systemic reforms, while a "Full Compensation" standard was preferred for more typical individual expropriations.

However, the narrative took another turn with a Supreme Court decision in 2002 (Heisei 14.6.11). This case concerned the constitutionality of the "price-fixing system at the time of project approval" (事業認定時価格固定制) under the revised Land Expropriation Act. This system generally values land at the time the public project is officially approved, with adjustments for general inflation up to the point of actual acquisition, but not necessarily for specific increases in land value that might be spurred by the project itself. The 2002 Supreme Court, in upholding this system, notably cited the 1953 "Reasonable Compensation" ruling as a key precedent, but did not cite the 1973 "Full Compensation" ruling.

This 2002 decision led to renewed debate. Some saw it as the Supreme Court reaffirming that "Reasonable Compensation" is the fundamental constitutional baseline, even for ordinary expropriations, with "Full Compensation" being more of a legislative policy goal than a strict constitutional mandate in all circumstances. The 2002 Court, much like the 1953 Court, emphasized that compensation must be "rationally calculated" and that legislative bodies have a degree of discretion in designing compensation schemes to serve public objectives, such as preventing speculative windfalls from public projects.

Legal commentators suggest that the Supreme Court has consistently focused on whether a specific compensation statute provides a "rationally calculated amount" within the bounds of legislative discretion. While the "Reasonable Compensation" theory from 1953 provides the overarching constitutional framework, specific statutory compensation schemes (like those in the Land Expropriation Act) are evaluated for how effectively they achieve the aim of making the property owner whole, an aim that resonates with the ideals of the Full Compensation theory. The 2002 judgment, for instance, while upholding a system that might not always yield full market value at the time of taking, still used language indicating that the system was designed to enable the expropriated owner to acquire equivalent substitute property.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's December 23, 1953, judgment in the Appeal Against Farmland Expropriation remains a cornerstone of Japanese constitutional law on property rights and state compensation. It affirmed the State's power to undertake radical socio-economic reforms deemed essential for the public welfare, even if the compensation provided to affected property owners did not meet the standard of full market value. By articulating and endorsing the "Reasonable Compensation" theory, the Court provided a legal framework that acknowledged the exigencies of post-war nation-building.

While the specific context of the land reform was unique, the principles laid down in this decision continue to inform legal debates about the balance between public necessity and private property rights, and the judiciary's role in scrutinizing the fairness and rationality of compensation mechanisms in Japan. The case highlights the complex considerations involved when the definition of "just" compensation is forged in the crucible of profound national transformation.