Judging in the Dark? Japan's Supreme Court Rejects In Camera Review for Undisclosed Government Documents

Decision Date: January 15, 2009

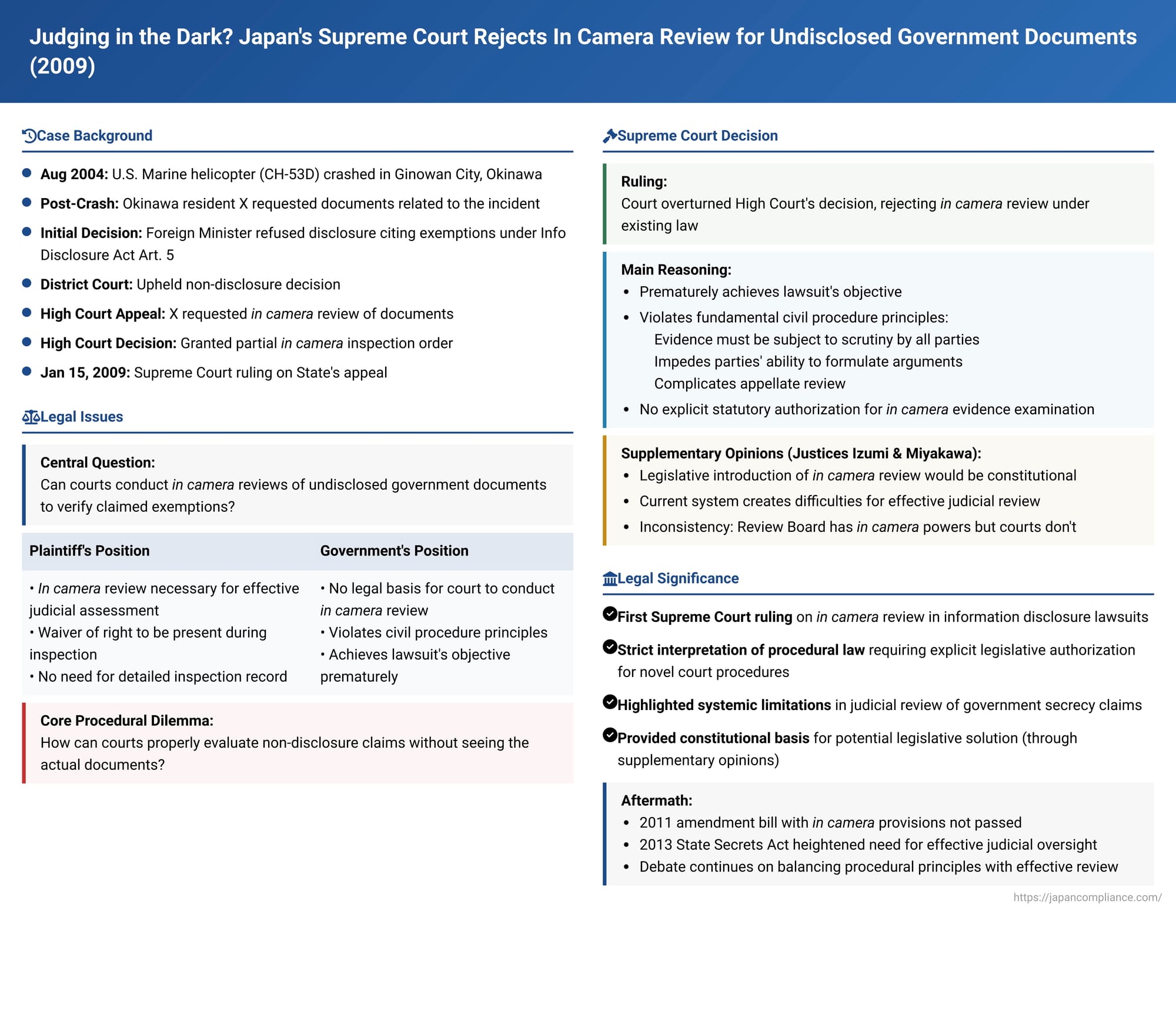

Information disclosure lawsuits present a unique challenge for courts: how can a judge fairly determine whether a government agency's refusal to release a document is justified without actually seeing the document in question? This procedural conundrum was at the heart of a Japanese Supreme Court decision on January 15, 2009 (Heisei 20 (Gyo-Fu) No. 5). The case concerned documents related to the crash of a U.S. military helicopter in Okinawa, and the plaintiff's request for an in camera review—a private inspection of the undisclosed documents by the judges alone—to assess the government's secrecy claims. The Supreme Court's ruling against such a procedure under existing law, despite acknowledging the inherent difficulties, has had significant implications for transparency litigation in Japan.

The Okinawa Helicopter Crash and the Quest for Information

In August 2004, a U.S. Marine Corps helicopter (CH-53D) crashed in Ginowan City, Okinawa Prefecture. X, a resident of Okinawa, subsequently filed a request under Japan's Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs (Information Disclosure Act) for administrative documents related to this incident. The Minister for Foreign Affairs, however, decided to withhold several documents (referred to as "the non-disclosed documents"). This non-disclosure decision was based on assertions that the documents contained information falling under exemptions in Article 5, item 1 (information concerning individuals), item 3 (information concerning national security, diplomatic relations, etc.), or item 5 (information concerning internal deliberations, examinations, etc.) of the Information Disclosure Act.

X challenged this decision, first through an administrative objection and then by filing a lawsuit against the State (Y) seeking the cancellation of the non-disclosure decision. The Fukuoka District Court, in the first instance, upheld the government's non-disclosure decision and dismissed all of X's claims.

During the appeal proceedings at the Fukuoka High Court, X argued that for the court to properly assess whether the non-disclosure exemptions were applicable, it was necessary for the judges to directly inspect the non-disclosed documents. X proposed a form of in camera inspection, offering to waive the right to be present during the court's examination of the documents. Furthermore, X stated they would not demand a detailed inspection record that might inadvertently reveal the specific contents of the sensitive documents. Based on this, X formally applied for a court order compelling the State to present the non-disclosed documents for this judicial inspection. The Fukuoka High Court partially granted X's application. It issued an order (the "original decision" in this appeal) requiring the State to present the non-disclosed documents for inspection, with the exception of those withheld solely under the personal information exemption (Article 5, item 1). The State, disagreeing with this order, filed a permitted appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (January 15, 2009): No Peeking Behind the Curtain

The Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, overturned the Fukuoka High Court's decision and dismissed X's application for an order to present the documents for inspection. The Court's reasoning was rooted in existing legal principles and the structure of the Information Disclosure Act.

Main Reasoning of the Court:

- Premature Achievement of Lawsuit's Objective: The Court stated that compelling the defendant (the State) to submit undisclosed documents for judicial inspection in an information disclosure lawsuit would, in effect, create a situation substantially identical to one where the non-disclosure decision had been cancelled and the documents disclosed to the plaintiff. This would prematurely achieve the ultimate objective of the lawsuit and was therefore deemed "unreasonable in light of the purpose of the information disclosure system" established by the Information Disclosure Act. Consequently, the Court found it impermissible to impose an obligation on the State to allow such an inspection or to order the presentation of documents for that purpose. X's proposal, even with the waiver of the right to be present, was characterized as a request for a de facto in camera hearing.

- Violation of Fundamental Civil Procedure Principles: A cornerstone of civil procedure, the Court emphasized, is that evidence used in litigation must be subjected to scrutiny and rebuttal by all parties involved. If an in camera hearing were conducted for the purpose of examining evidence (i.e., the content of the undisclosed documents) to determine the applicability of non-disclosure exemptions, the court would directly inspect the documents to make its substantive judgment. However, the plaintiff (X) would be unable to see the documents to formulate arguments based on their actual content, and the defendant (Y) would also be constrained from fully utilizing the specific contents of the documents in its own arguments during such a closed process. Moreover, if a court based its judgment on such an in camera review, it would become difficult for the losing party to articulate precise grounds for appeal, and the appellate court, in turn, would have to review the lower court's decision without being able to directly verify the primary evidence upon which that decision was based. The Supreme Court concluded that conducting an in camera hearing as a method of evidence examination in information disclosure lawsuits contravenes these fundamental principles of civil procedure and is therefore impermissible unless explicitly authorized by statute.

- Absence of Explicit Statutory Authorization: The Court then examined whether existing laws provided for such a procedure. It noted that while certain provisions in the Code of Civil Procedure (e.g., former Article 223, paragraph 3, and Article 232, paragraph 1) allow for in camera procedures, these are limited to the specific purpose of helping a court decide on the admissibility of evidence—that is, whether or not to issue an order for document production in the first place. They do not authorize the evidence examination itself to be conducted privately. Even subsequent amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure (e.g., Article 223, paragraph 6, and Article 232, paragraph 1, which expanded in camera review for decisions on document production orders concerning documents held by public officials) did not introduce provisions for in camera evidence examination in information disclosure lawsuits.

The Information Disclosure Act itself, enacted in 1999, provided that the Information Disclosure Review Board (an administrative review body) could inspect undisclosed documents in camera as part of its investigation (former Article 27, paragraph 1). However, no corresponding provision granting such power to the courts was included in the Act. The Supreme Court interpreted this legislative choice as deliberate, reasoning that the adoption of in camera hearings in judicial proceedings was deferred due to existing diverse views on its compatibility with the principle of open trials (Constitution Article 82) and the significant implications of allowing judgments based on evidence not fully vetted by the opposing party, which touches upon the fundamentals of the litigation system.

Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded that under current law, courts are not permitted to conduct in camera hearings to examine the content of undisclosed documents in information disclosure lawsuits. Even if the plaintiff, like X, offers to waive procedural rights such as the right to be present, the State cannot be legally compelled to submit to such an inspection of the documents, and therefore, cannot be ordered to present them for this purpose. The High Court's decision ordering the presentation was thus found to be based on a clear misinterpretation of the law that affected the judgment. X's application for an order to present the documents was deemed improper and was dismissed.

Supplementary Opinions: Acknowledging the Dilemma, Pointing to Legislation

Two justices, Justice Tokuji Izumi and Justice Kōji Miyakawa, appended supplementary opinions to the decision, agreeing with the outcome but offering further reflections on the underlying issues.

Justice Izumi's Supplementary Opinion:

Justice Izumi concurred that conducting an in camera evidence examination where the plaintiff cannot see the document and argue based on its content violates fundamental civil procedure principles, such as the right of parties to participate in evidence examination and the inability to use evidence not subjected to party scrutiny as a basis for judgment. He noted that the plaintiff's waiver of the right to be present would not rectify these issues, as the defendant agency would also be hampered in its ability to argue by referencing the document's specific content, and appellate review would be compromised.

However, Justice Izumi significantly opined that the legislative introduction of in camera hearings specifically for information disclosure lawsuits would not violate Constitution Article 82 (guaranteeing public trials) and would fall within the scope of legislative discretion in shaping the litigation system. He argued that such a procedure could strengthen the judicial protection of the right to access administrative documents—itself a concretization of the people's right to know—enhance public trust in the judiciary, and more fully realize the right to access courts guaranteed by Constitution Article 32.

Justice Miyakawa's Supplementary Opinion:

Justice Miyakawa also agreed that the High Court's decision went beyond permissible legal interpretation and had to be overturned. However, he expressed understanding for the High Court's underlying concern: that without a mechanism for direct judicial inspection, courts might effectively be forced to rely solely on the opinions of the government agency or its advisory body (the Information Disclosure Review Board) when judging non-disclosure claims, which would severely undermine the judiciary's intended role as the final arbiter in disclosure disputes. He viewed the case as a compelling example illustrating the need to consider introducing in camera hearings in information disclosure lawsuits.

He pointed out that such lawsuits can present significant difficulties for courts to make appropriate judgments about non-disclosure grounds without seeing the documents, often leading to lengthy and indirect methods of deliberation based on peripheral evidence. This creates a desire on the part of plaintiffs for in camera review, at least to ensure the court itself can directly assess the documents. Furthermore, the existence of an in camera review mechanism could serve as a deterrent against inappropriate non-disclosure decisions by administrative agencies. Justice Miyakawa echoed Justice Izumi's view that in camera review would not contravene Constitution Article 82, drawing parallels with existing provisions for private hearings in personnel litigation, trade secret cases, and patent litigation. He suggested that if the administrative agency is given an opportunity to explain its reasons for non-disclosure prior to the in camera review, due process concerns could be addressed. He also highlighted an inconsistency in the current system: while the administrative-level Information Disclosure Review Board has the power of in camera inspection (under the Information Disclosure and Personal Information Protection Review Board Establishment Act, Article 9, paragraphs 1 and 2), the courts, which are meant to be the final arbiters, lack this tool. He advocated for consideration of in camera hearings in court, potentially combined with Vaughn Index-like procedures (where agencies are required to provide detailed, itemized justifications for non-disclosure, as referenced in Article 9, paragraph 3 of the Review Board Establishment Act).

The Legal Landscape of In Camera Review in Japan (Commentary Insights)

This 2009 Supreme Court decision was the first by the nation's highest court specifically on the issue of in camera hearings in information disclosure lawsuits. The core of the dispute was whether courts could conduct what amounts to a de facto private substantive review of undisclosed documents to rule on the merits of a non-disclosure decision, in the absence of explicit statutory authorization.

The commentary on the case underscores several key points:

- No Explicit Legal Basis: As the Supreme Court found, there is no explicit provision in the Information Disclosure Act authorizing courts to conduct such in camera evidence examinations. While the Code of Civil Procedure does allow for certain in camera procedures, these are strictly limited to assisting the court in deciding whether or not to issue a document production order (i.e., assessing the validity of a claim of privilege over a document whose production is sought), not for the examination of the document's content as evidence for the main issue of the lawsuit.

- Review Board vs. Courts: In contrast to the courts, the Information Disclosure and Personal Information Protection Review Board (an administrative body that reviews objections to non-disclosure decisions) is explicitly empowered by its establishing statute to conduct in camera reviews of undisclosed documents and to utilize procedures resembling a Vaughn Index, which requires the administrative agency to provide a detailed index and justification for each claimed exemption.

- Previous Lower Court Stances: Prior to this Supreme Court decision, some lower courts, such as the Tokyo District Court and Tokyo High Court in other cases, had already rejected in camera hearings for reasons similar to those eventually adopted by the Supreme Court. The Fukuoka High Court's decision in the present case, which approved the in camera inspection, was therefore an outlier, driven by its concern that courts must have a way to fulfill their duty as the final arbiter of disclosure disputes. There had also been a few exceptional instances where de facto in camera reviews reportedly occurred in lawsuits under local information disclosure ordinances.

- Constitutional Considerations: While the Supreme Court's majority opinion did not delve into constitutional arguments, the supplementary opinions did. They argued that legislating for in camera review in information disclosure lawsuits would not violate the constitutional guarantee of public trials (Article 82) and could, in fact, enhance the right to access courts (Article 32) by making judicial review more effective. Academic discourse on the constitutional permissibility of in camera review is varied. Some scholars argue for its necessity based on a combined reading of Articles 32 and 82, possibly requiring specific legislation, while others suggest it might be an inherent judicial power under Article 76 (judicial power) even without explicit statutory authorization. The supplementary opinions in this case are seen as providing a constitutional basis for the future legislative introduction of in camera review.

- Civil Procedure Perspectives: From a civil procedure standpoint, the prevailing view aligns with the Supreme Court's majority: in camera evidence examination (as distinct from admissibility hearings) clashes with fundamental principles like the adversarial process (where both parties confront and challenge evidence) and the right to be heard on the evidence presented. A plaintiff's waiver of the right to be present does not fully address these concerns, as it impacts the defendant's ability to argue and complicates appellate review. However, some counterarguments exist, emphasizing that if a plaintiff has no other means to substantiate their claim (a "last resort"), and given appropriate waivers and the nature of the documents, in camera review might facilitate objective and thorough judicial assessment without fundamentally violating core principles. Alternative forms, like "de facto in camera review as part of a settlement" (where a document holder voluntarily submits a document for judges' eyes only, usually leading to withdrawal of the suit) or "in camera review for case management purposes" (conducted with the agreement of all parties to clarify issues), might not conflict with these principles.

Implications and the Path Forward

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision solidified the legal position that, under the then-existing statutory framework, Japanese courts could not order or conduct in camera examinations of the contents of undisclosed documents as part of the evidence-gathering process in information disclosure lawsuits. This has clear implications for how such lawsuits are litigated, often forcing plaintiffs and courts to rely on indirect evidence and arguments to challenge government secrecy claims.

The debate over in camera review remains highly relevant. The enactment of the Act on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets in 2013, which deals with highly sensitive national security information, has further highlighted the potential need for effective judicial oversight mechanisms, including in camera review, to ensure that secrecy classifications are not abused. Notably, a bill to amend the Information Disclosure Act, which included provisions for introducing in camera judicial review, was submitted to the Diet in April 2011 but was ultimately not passed and was scrapped after the Diet session ended. The arguments presented in the supplementary opinions by Justices Izumi and Miyakawa, advocating for legislative action, continue to resonate, pointing towards a potential future direction for reform aimed at enhancing the effectiveness and credibility of judicial review in information disclosure cases.

Conclusion

The January 15, 2009, Supreme Court decision firmly closed the door on court-ordered in camera evidence examination in information disclosure lawsuits under the existing legal framework in Japan. While grounded in established principles of civil procedure and a strict interpretation of statutory authority, the ruling also brought into sharp relief the practical difficulties faced by courts in adjudicating such cases and the strong arguments for legislative reform. The supplementary opinions, in particular, signaled a judicial acknowledgment of the system's limitations and provided constitutional support for a future legislative solution that could equip courts with the tools deemed necessary for a more robust and effective oversight of government secrecy claims, thereby better fulfilling the objectives of the Information Disclosure Act and strengthening the public's right to know.