Joyriding as Grand Theft Auto? A Japanese Ruling on 'Temporary Use' and Theft

If you "borrow" a neighbor's bicycle without asking for a quick trip to the store and then promptly return it, have you committed a crime? What if it's not a bicycle, but their brand-new car, and you take it for a multi-hour joyride through the city before returning it? The line between non-criminal "unauthorized temporary use" and the serious crime of theft can be blurry, and it hinges on the perpetrator's state of mind.

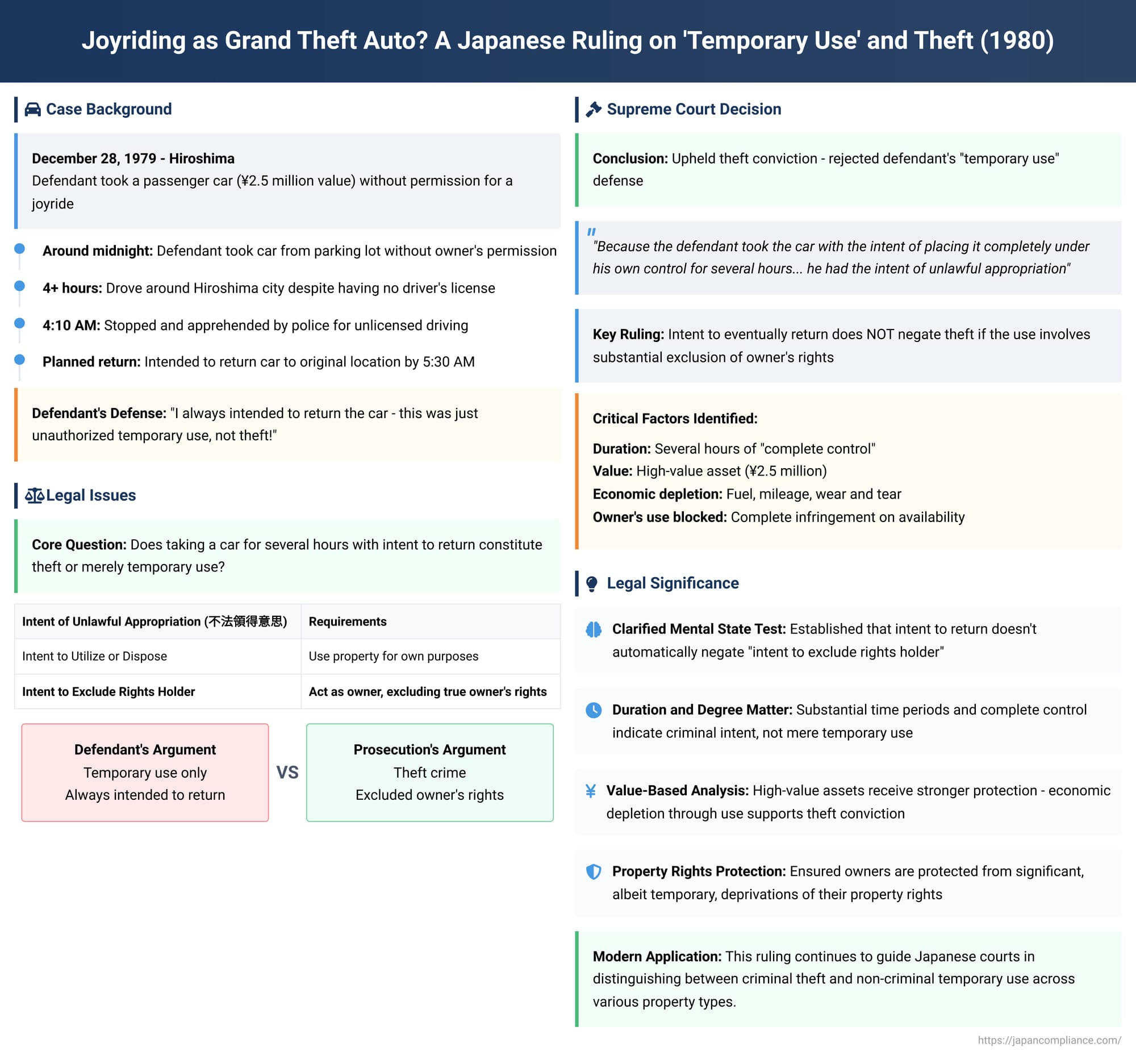

A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on October 30, 1980, tackled this very issue. The case, involving a man who took a car for a four-hour joyride, provided a foundational ruling on how Japanese law distinguishes punishable theft from simple "use theft" (shiyō settō). The Court's decision centered on the crucial legal concept of the "intent of unlawful appropriation," specifically the "intent to exclude the rights holder" from their property.

The Facts: The Four-Hour Joyride

The facts of the case were straightforward. Around midnight on December 28, 1979, the defendant took a passenger car, valued at approximately 2.5 million yen, from a parking lot in Hiroshima without the owner's permission. He then drove the car around the city for over four hours, despite not having a driver's license. At around 4:10 AM, he was stopped and apprehended by the police for driving without a license.

During the legal proceedings, it was established that the defendant had intended to return the car to its original location by 5:30 AM, meaning his total planned use was about five and a half hours. He argued that because he always intended to return the vehicle, his act was merely unauthorized temporary use, not theft.

The Legal Doctrine: Why Isn't All "Borrowing" a Crime?

The defendant's argument highlights a core problem in theft law. The objective act of taking an object from another's possession against their will technically fits the basic definition of theft. A simple, common-sense example illustrates the issue: borrowing a colleague's ruler for a moment without asking should not be a crime. To solve this, Japanese case law and mainstream legal scholarship have established that a conviction for theft requires more than just the basic intent to take; it requires a special, additional subjective element known as the "intent of unlawful appropriation" (fuhō ryōtoku no ishi).

This intent is traditionally understood to have two distinct components:

- Intent to Utilize or Dispose: The perpetrator must intend to use or dispose of the property for their own purposes, according to its economic function. This is what distinguishes theft from the simple crime of property destruction.

- Intent to Exclude the Rights Holder (kenrisha haijo ishi): The perpetrator must intend to exclude the true owner from their rights and act as if the property were their own, at least for the duration of the use. This is the crucial component that distinguishes criminal theft from non-criminal temporary use.

The joyriding case put this second component directly under the Supreme Court's microscope.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Time and Control Create Intent

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's argument and upheld his conviction for theft. The Court's reasoning focused on the duration and nature of the defendant's control over the car.

The Court held that because the defendant took the car "with the intent of placing it completely under his own control for several hours," he had demonstrated the necessary "intent of unlawful appropriation."

The most critical part of the Court's brief ruling was its dismissal of the defendant's primary defense:

"...even if he intended to return it to its original place after use, it must be said that the defendant had the intent of unlawful appropriation for the said car."

This statement made it clear that a mere intent to eventually return an item is not a "get out of jail free" card. The quality of the use, not just its ultimate duration, is what determines criminal liability.

Analysis: Drawing the Line Between Use and Exclusion

The Supreme Court's decision confirms that the line between permissible temporary use and criminal theft is a matter of substance and degree. While the "intent to exclude the rights holder" is a subjective element, courts determine its existence by looking at objective factors surrounding the act. Key factors include:

- Duration and Degree of Control: While a momentary use of a low-value item might not qualify, the Court found that taking a valuable car for "several hours" and placing it under one's "complete control" was significant enough to constitute a criminal exclusion of the owner's rights.

- Value of the Object: The high value of the automobile (2.5 million yen) was explicitly mentioned by the court and is a critical factor. The law treats the unauthorized use of a high-value asset far more seriously than that of a trivial one.

- Economic Depletion: The use of a car intrinsically consumes its value through fuel consumption, mileage, and general wear and tear. This consumption of the item's inherent economic value is a key indicator that the user is treating the property as their own, thereby excluding the owner's rights. This contrasts sharply with cases like borrowing a bicycle for a short trip, where lower courts have found the negligible depletion in value to be a reason to deny the intent to exclude.

- Infringement on the Owner's Use: By taking the car for several hours in the middle of the night, the defendant made it impossible for the true owner to use it, should the need have arisen. This complete infringement on the owner's "possibility of use" is central to the finding of exclusion.

This principle has also been applied to intangible property. In cases involving the unauthorized copying of confidential company documents, for example, courts have found the "intent to exclude" to be satisfied. Even though the physical documents were returned, the exclusive value of the information they contained was consumed or depleted by the act of copying, thereby infringing on the owner's rights in a manner equivalent to theft.

Conclusion: A Matter of Substance, Not Just Intent

The 1980 Supreme Court joyriding case provides a foundational lesson in Japanese theft law. It clarifies that to avoid a theft conviction for temporary use, the use must be truly minor and transient. The decision establishes that the "intent to exclude the rights holder" is not negated simply by an eventual plan to return the item.

Instead, courts will look at the entire context of the act. When a person takes a high-value asset, places it under their complete control for a substantial period, and consumes its economic value, their actions speak louder than their stated intent. Such conduct demonstrates a substantive decision to treat another's property as one's own, satisfying the requirements for the crime of theft. The ruling ensures that the law draws a common-sense line, protecting property owners from significant, albeit temporary, deprivations of their rights, and confirming that a joyride can indeed be grand theft auto.