Joint Tax Liability and Creditor Rights: Japanese Supreme Court on Determining Tax Claim Priority

Judgment Date: July 14, 1989

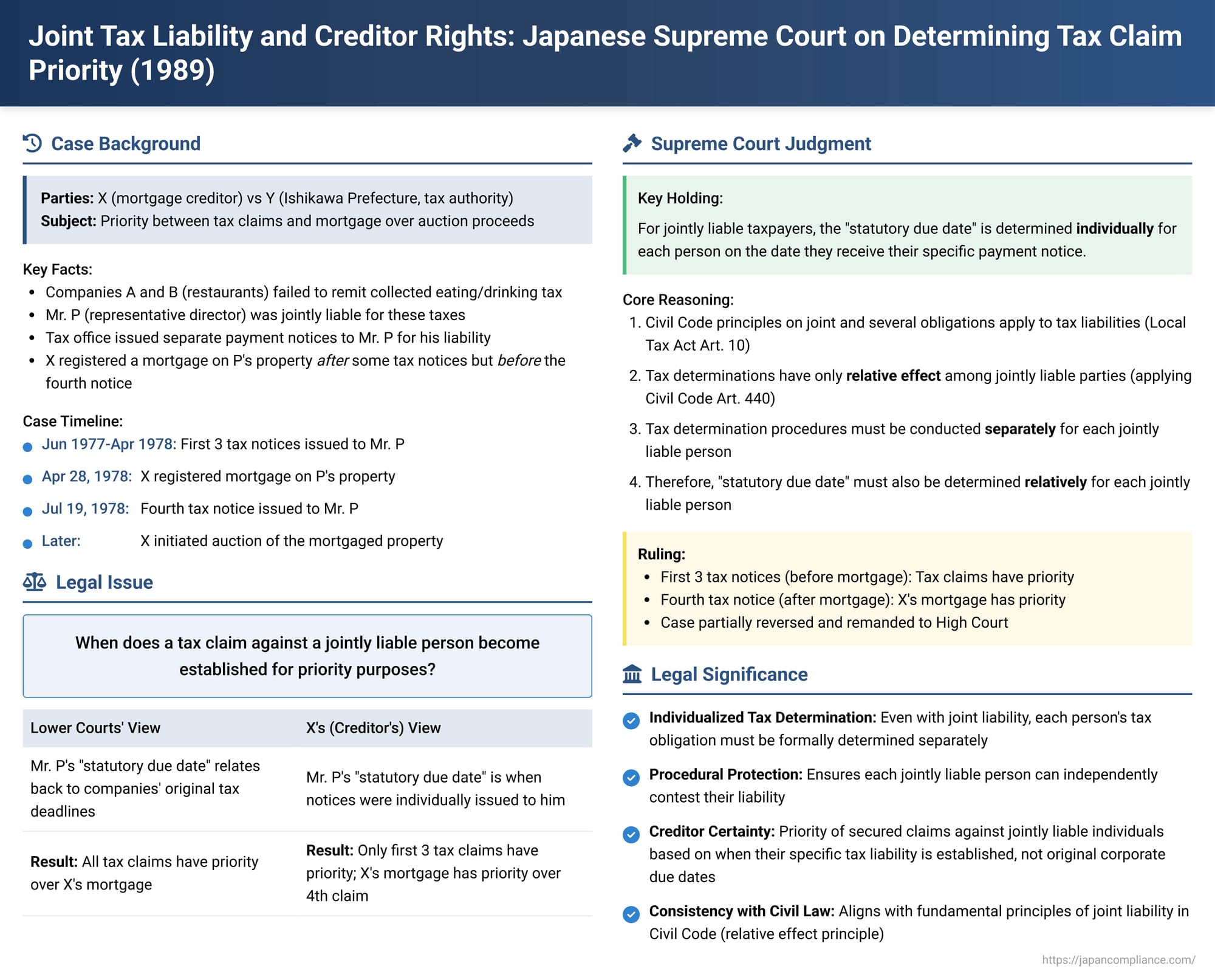

In a pivotal decision clarifying the rights of creditors in relation to tax claims against individuals who are jointly and severally liable for taxes primarily owed by other entities (such as corporations they manage), the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan addressed how the priority between a tax claim and a private mortgage should be determined. The ruling emphasized that for a jointly and severally liable taxpayer, the critical date for establishing the tax claim's priority – its "statutory due date, etc." – is when that individual's specific liability is formally determined and notified, not when the tax was originally due from the primary corporate taxpayer.

Background: A Defunct Restaurant Business and Competing Claims

The case arose from the financial aftermath of a defunct restaurant business. Two companies, "A Co." and "B Co.," operated several food and beverage establishments and were designated as "special collection agents" for the now-abolished "eating and drinking tax" (ryōinzei - 料飲税). This local consumption tax required businesses like restaurants to collect the tax from their customers and remit it to the prefecture. This "special collection" system is analogous to the withholding tax system for national taxes.

Mr. P was the representative director of both A Co. and B Co. Under the Local Tax Act (Article 10-2, Paragraphs 2 and 3), Mr. P was also designated as being jointly and severally liable (rentai nōzei gimu - 連帯納税義務) with A Co. and B Co. for the collection and remittance of this eating and drinking tax.

Both A Co. and B Co. became delinquent in remitting the collected taxes to Y (Ishikawa Prefecture, the taxing authority). Consequently, Y's Kanazawa Prefectural Tax Office initiated tax delinquency dispositions against the two companies. Simultaneously, the tax office pursued Mr. P as a jointly and severally liable party for the unpaid taxes. Between June 18, 1977, and July 19, 1978, the tax office made four separate determinations of the specific tax amounts Mr. P was liable to pay (pursuant to former Local Tax Act Article 124, Paragraph 2). For each determination, a "determination notice and payment notice" (kettei tsūchisho ken nōnyū kokuchisho) was issued and served on Mr. P, formally assessing his liability.

The Mortgagee's Claim and the Auction

Meanwhile, X (a fire and marine insurance mutual company, the appellant), was a creditor of Mr. P. Aware of the deteriorating financial situation of A Co. and B Co., X took steps to secure its claims against Mr. P. After the tax office had issued its third payment notice to Mr. P, X obtained a mortgage over real estate owned by Mr. P. This mortgage was formally registered on April 28, 1978.

Subsequently, X initiated a "voluntary auction" (a type of non-judicial foreclosure proceeding available to mortgagees under Japanese law at the time, similar to exercising a power of sale) of Mr. P's mortgaged property.

The Dispute Over Auction Proceeds

During the distribution of the proceeds from the property auction, a dispute arose over the priority between Y's tax claim against Mr. P and X's mortgage claim. Y had submitted a "demand for allocation" (kōfu yōkyū) to the auction court, seeking payment of Mr. P's delinquent eating and drinking taxes from the sale proceeds.

The general rule in Japan for determining priority between tax claims and private secured rights (like mortgages) is governed by provisions in the National Tax Collection Act and the Local Tax Act (specifically, Local Tax Act Articles 14-9 and 14-10 for this case). In principle, a pre-existing perfected secured right (e.g., a mortgage registered before the tax claim's critical date) takes priority over the tax claim. The critical date for the tax claim is its "statutory due date, etc." (hōtei nōkigen tō - 法定納期限等). This date generally signifies when the existence and amount of the tax liability become objectively clear.

For the eating and drinking tax, the "statutory due date, etc." was defined as the original filing deadline if the tax was properly declared and paid by then. However, if the tax liability was determined later (e.g., through an assessment on a delinquent or non-filing party), the "statutory due date, etc." became the date on which the payment notice was issued to that party (Local Tax Act Article 14-9, Paragraph 1, Item 1).

The auction court (Kanazawa District Court) prepared a distribution plan that gave priority to Y's fourth tax claim against Mr. P (arising from the payment notice issued to P on July 19, 1978) over X's mortgage. The court's reasoning was that the "statutory due date, etc." for determining Mr. P's liability effectively related back to the original filing deadlines applicable to the primary obligors, A Co. and B Co. Since those original corporate deadlines predated the registration of X's mortgage (April 28, 1978), the tax claim was deemed to have priority.

X objected to this distribution plan, arguing that for Mr. P's distinct liability as a jointly and severally liable party, the "statutory due date, etc." should be the date the specific payment notice was issued directly to Mr. P. For the fourth tax claim against P, this was July 19, 1978, which was after X's mortgage was registered. Thus, X contended its mortgage should have priority. X filed a lawsuit to challenge the auction court's distribution plan.

The Kanazawa District Court (in the lawsuit) and subsequently the Nagoya High Court, Kanazawa Branch (on appeal) both dismissed X's claim, upholding the priority of the tax authority's claim based on the relation-back theory. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis and Decision: Individualized Determination is Key

The Supreme Court partially reversed the High Court's decision, finding that the lower courts had erred in their interpretation of how the "statutory due date, etc." should be determined for a jointly and severally liable taxpayer like Mr. P.

Applicability of Civil Code Principles to Joint Tax Liability

The Court began by noting that Article 10 of the Local Tax Act provides that the Civil Code's provisions concerning joint and several obligations (specifically, former Articles 432-434, 437, and 439-444 of the Civil Code, as it stood before later amendments) apply mutatis mutandis to joint and several tax payment obligations.

Tax Determination Has Only Relative Effect Among Jointly Liable Parties

The crucial part of the Supreme Court's reasoning was its interpretation of the effect of tax determination procedures on jointly liable parties:

"Regarding joint and several payment obligations for local government levies, while provisions of the Civil Code concerning joint and several obligations are applied mutatis mutandis (Local Tax Act Article 10), the effect of a tax amount determination (zeigaku kakutei no kōryoku) made with respect to one jointly and severally liable payer does not have absolute effect in relation to other jointly and severally liable payers. By application of Article 440 of the Civil Code [former version, dealing with events having only relative effect], it merely produces a relative effect. Accordingly, it is appropriate to understand that the procedure for determining the tax amount for a jointly and severally liable payer must be conducted separately for each such jointly and severally liable payer."

"Statutory Due Date, etc." is Also Determined Relatively

Flowing from this principle of relative effect for tax determination, the Court concluded:

"Therefore, when applying Article 14-10 of the Local Tax Act [which governs priority], the 'statutory due date, etc.' should also be determined relatively for each jointly and severally liable payer in accordance with this [principle of separate determination]."

Application to Mr. P's Case

Applying these principles to the facts:

- For A Co. and B Co. (the primary corporate taxpayers), their "statutory due date, etc." would indeed be their original statutory due dates for filing and payment (or the actual date of filing if a late return was accepted that fixed the liability).

- However, the Supreme Court stated: "This fact does not in any way establish P's tax liability or create the effect of deeming P's statutory due date, etc., to be the same as those [of A Co. and B Co.]."

- For Mr. P, his "statutory due date, etc." must be understood as the respective dates on which the said determination notices and payment notices, which had the effect of establishing his specific tax liability, were issued to him. This was clear from the Court's preceding explanation.

The lower courts had therefore erred in law by holding that the "statutory due date, etc." for Mr. P's tax claims related back to the original due dates of A Co. or B Co., rather than the dates the payment notices were issued directly to Mr. P.

Judgment and Its Implications

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court ruled:

- The portion of the High Court's judgment that had dismissed X's claim concerning the priority of the fourth tax notice issued to Mr. P (on July 19, 1978, which was after X's mortgage registration on April 28, 1978) was reversed. This part of the case was remanded to the Nagoya High Court. The High Court was instructed to re-examine the existence and amount of X's secured mortgage claim and then re-determine the priority of distribution based on the Supreme Court's ruling that P's relevant "statutory due date, etc." for this tax portion was July 19, 1978. This would give X's mortgage priority over this specific tax claim.

- The remainder of X's appeal (which implicitly concerned the first three tax notices issued to P before X's mortgage was registered, and for which the tax claim would thus have priority) was dismissed.

Significance of the Ruling:

This 1989 Supreme Court decision has lasting importance for several reasons:

- Individualized Tax Determination for Jointly Liable Parties: It is a landmark affirmation that, even in cases of joint and several tax liability, the tax liability of each individual jointly liable person must be formally and separately determined through procedures specifically directed at that person. A determination against one primary obligor (like a company) does not automatically crystallize the liability or the critical "statutory due date, etc." for other jointly liable individuals (like its representative director).

- Protection of Procedural Rights: This ensures that each jointly liable person has the opportunity to contest their own liability, as procedural actions against one do not bind others without separate proceedings.

- Certainty for Third-Party Creditors: The ruling provides greater certainty for creditors of individuals who might also be jointly liable for corporate taxes. The priority of a creditor's secured claim (like a mortgage) against such an individual will be determined based on when the tax liability of their specific debtor was formally established and notified to that debtor, not by relating back to the original due dates of the primary corporate taxpayer. This prevents a creditor from being unexpectedly subordinated to tax claims that were not clearly established against their debtor at the time the security was taken.

- Consistency with Civil Law Principles: The Court's emphasis on the relative effect of actions concerning one joint debtor aligns with fundamental principles of joint and several liability in the Civil Code, ensuring consistency between tax law and general private law in this regard. (It's noteworthy that subsequent revisions to the Japanese Civil Code concerning joint and several obligations, effective from April 1, 2020, have further reinforced the principle of relative effect for most events, including demands for performance. Corresponding amendments were also made to tax laws like the Act on General Rules for National Taxes and the Local Tax Act in 2017, making the Supreme Court's reasoning in this case, which focused on the individual nature of tax determination, highly prescient and aligned with current legal thought.)

This judgment clarifies a crucial aspect of tax collection involving multiple liable parties, safeguarding both the procedural rights of jointly liable taxpayers and the predictability needed by their private creditors. It underscores that tax procedures, even when dealing with joint liabilities, must respect the individual legal position of each party involved.