Joint Mortgages, Sureties, and Junior Lenders: Untangling Priorities in Japanese Foreclosures

Date of Judgment: May 23, 1985

Case Name: Action for Objection to Distribution Table

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

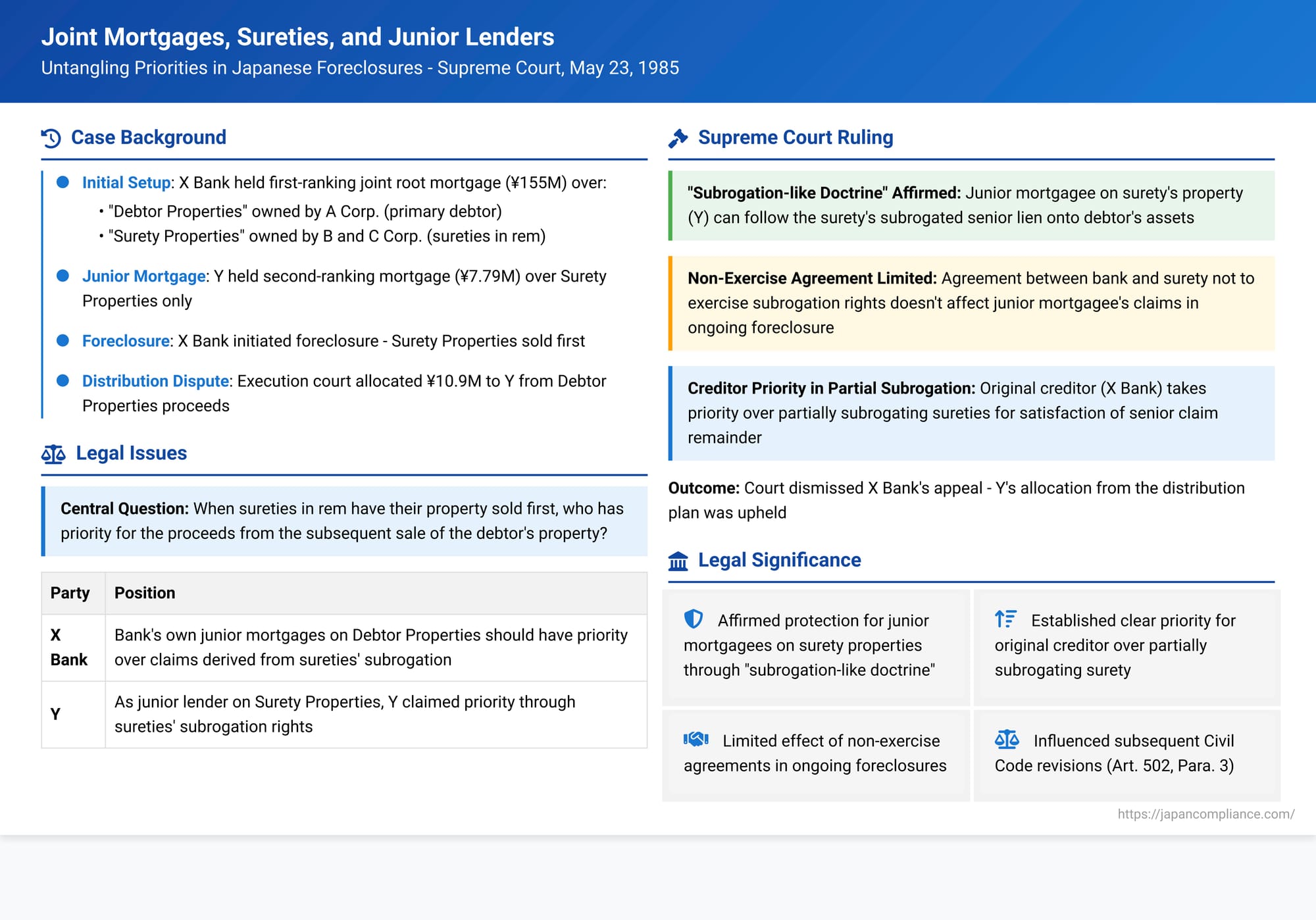

Joint mortgages, which secure a single debt using multiple properties, can become particularly complex when some of those properties are owned by the primary debtor and others by third parties acting as "sureties in rem" (butsujō hoshōnin). These sureties pledge their own property to secure another person's debt. When such a jointly mortgaged security package is foreclosed, especially if there are also junior mortgagees with claims against different properties within the package, determining the correct order of payment (priority) from auction proceeds can be a significant challenge. The Supreme Court of Japan provided crucial guidance on these intricate priority rules in a judgment on May 23, 1985.

The Intricate Web of Security: Mortgages, Sureties, and Guarantees

The case involved a primary creditor, X Bank, a primary debtor, A Corp., and two sureties in rem, B (an individual) and C Corp. (a company). There was also a junior mortgagee, Y, whose rights became central to the dispute.

- X Bank's Senior Joint Root Mortgage: X Bank held a first-ranking joint root mortgage (kyōdō neteitōken) with a maximum credit limit of ¥155 million. This mortgage encumbered a collection of properties:

- Properties owned by the primary debtor, A Corp., and another third party (collectively referred to as the "Debtor Properties").

- Properties owned by the sureties in rem: land owned by B and a building owned by C Corp. (collectively referred to as the "Surety Properties").

- Y's Junior Mortgage: Separately, Y had lent ¥7.79 million to B (one of the sureties in rem) and two other individuals as joint debtors. To secure this loan, Y held a second-ranking mortgage specifically over the Surety Properties (B's land and C Corp.'s building).

- X Bank's Other Mortgages: X Bank also held further, more junior, root mortgages over both the Debtor Properties and the Surety Properties, but these were subordinate to its own first-ranking joint root mortgage and, in the case of the Surety Properties, also subordinate to Y's second-ranking mortgage.

- Non-Exercise of Subrogation Rights Agreement: An important side agreement existed between X Bank (the senior mortgagee) and B (one of the sureties in rem). B had agreed that if he were to acquire any rights by subrogation against A Corp. (e.g., after his property was sold to pay A Corp.'s debt to X Bank), he would not exercise these subrogated rights without X Bank's consent as long as X Bank's lending relationship with A Corp. continued. This is known as a "non-exercise of subrogation rights agreement" (daiken fukōshi tokuyaku).

- Foreclosure and Initial Distribution: X Bank initiated foreclosure proceedings based on its first-ranking joint root mortgage against all the encumbered properties (both Debtor Properties and Surety Properties).

- The Surety Properties (owned by B and C Corp.) were sold first at auction. From the proceeds of this sale, X Bank received a partial payment of approximately ¥17.81 million towards A Corp.'s massive outstanding debt (which totaled over ¥1.13 billion in principal and damages).

- Subsequently, the Debtor Properties (owned by A Corp. et al.) were also sold at auction, generating proceeds of ¥600 million.

- The Disputed Distribution Plan: The execution court (Sendai District Court) then prepared a distribution plan for the ¥600 million proceeds from the Debtor Properties. This plan proposed to pay:

- A portion to X Bank for its own junior mortgages on the Debtor Properties (which had effectively moved up in rank after its senior mortgage was partially satisfied from the Surety Properties' sale).

- Then, significantly, approximately ¥10.9 million to Y. This payment to Y was based on the theory that the sureties B and C Corp., whose properties were sold first, had subrogated to X Bank's original first-ranking mortgage rights against the Debtor Properties. Y, as a junior mortgagee on the Surety Properties, was then claiming a right to be paid from this subrogated first-ranking interest.

- The remainder would go to X Bank for its further claims.

The execution court essentially reasoned that Y's claim, derived from the sureties' subrogation to X Bank's initial first-rank position on the Debtor Properties, took priority over X Bank's own junior-ranking mortgages on those same Debtor Properties.

- X Bank's Objection: X Bank objected to this distribution plan. It argued that its own direct junior mortgages on the Debtor Properties should have priority over any rights Y might be claiming derivatively through the sureties. X Bank also contended that the "non-exercise of subrogation rights" agreement with surety B should prevent B (and by extension, Y, if Y's claim was through B) from asserting any subrogated rights that would prejudice X Bank.

The District Court and the High Court both dismissed X Bank's objection. X Bank then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (May 23, 1985): Key Rulings on Priorities

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed X Bank's appeal, largely upholding the principles that favored Y's priority in this specific context, although it did clarify aspects of how the distribution should be calculated. The judgment provided important guidance on three key issues:

1. Priority Between Junior Mortgagees When a Surety in Rem's Property is Sold First (The "Subrogation-like Doctrine"):

The Court addressed the situation where properties of a primary debtor and a surety in rem are jointly mortgaged to a senior creditor (like X Bank), and different junior mortgagees exist on the debtor's properties versus the surety's properties.

- Surety's Subrogation: If the surety in rem's property is sold first in a foreclosure by the senior mortgagee, and the senior mortgagee receives payment from those proceeds, the surety in rem (here, B and C Corp.) acquires two things: (a) a reimbursement claim against the primary debtor (A Corp.) for the amount paid on their behalf, and (b) by way of legal subrogation (under the then-Civil Code Article 500, now Article 501), the surety steps into the shoes of the senior mortgagee and acquires that senior mortgagee's (X Bank's) original first-ranking mortgage rights over the debtor's remaining properties.

- Junior Mortgagee on Surety's Property Benefits: Crucially, the Supreme Court affirmed (citing its precedent from July 4, 1978, Minshū Vol. 32, No. 5, p. 785) that the junior mortgagee who held a mortgage on the surety's property (i.e., Y) is entitled to receive payment from this subrogated first-ranking mortgage (now effectively held by the surety for reimbursement purposes) with priority over any junior mortgagees who hold mortgages only on the debtor's property.

This is often referred to as a "subrogation-like doctrine" (butsujō daii ruiji no hōri) or a rule governing "different-time distribution" (iji haitō) in joint mortgages. It allows the junior mortgagee on the surety's property to effectively "follow" the surety's subrogated senior lien onto the debtor's other assets.

2. The Limited Effect of a "Non-Exercise of Subrogation Rights" Agreement in this Context:

The Court then considered the agreement between X Bank and surety B, where B promised not to exercise subrogated rights without X Bank's consent.

- The Court held that such an agreement does not negate or diminish the right of the junior mortgagee on the surety's property (Y) to receive priority payment from the surety's subrogated mortgage under the circumstances of an ongoing execution initiated by the senior creditor.

- Rationale: The junior mortgagee (Y) benefits from the surety's (B's) subrogated first-ranking mortgage because the surety automatically subrogates upon the sale of their property to satisfy the senior debt. The junior mortgagee then exercises rights against this subrogated mortgage "as if by subrogation" to the surety's right. The non-exercise agreement between X Bank and B was interpreted narrowly by the Court. It was seen as primarily intended to prevent the surety (B) from independently initiating enforcement of the subrogated mortgage (e.g., by starting their own foreclosure on the debtor's property) in a manner that might conflict with X Bank's ongoing collection efforts or strategy while X Bank's main dealing with the primary debtor (A Corp.) was still active. It was not interpreted as extinguishing the junior mortgagee's (Y's) derivative priority right when X Bank itself was already foreclosing and proceeds were being distributed.

3. Creditor's Priority in Cases of Partial Subrogation by a Surety in Rem:

This part of the judgment addressed the scenario where the senior creditor (X Bank) receives only partial satisfaction of its debt from the sale of the surety in rem's property.

- The Court clarified that when this happens, the surety in rem (B and C Corp.) can, under the provisions of the then-Civil Code Article 502, Paragraph 1, exercise the creditor's remaining mortgage rights over other collateral (like A Corp.'s Debtor Properties) concurrently with the original creditor (X Bank).

- However, when it comes to the distribution of proceeds from the sale of that remaining collateral (the Debtor Properties), the original creditor (X Bank) takes priority over the partially subrogating surety (B and C Corp.) for the satisfaction of the remainder of the creditor's own senior claim.

- Rationale: The Court reasoned that subrogation by payment is a mechanism designed to secure the reimbursement claim of the party who paid the debt (the surety). It is not intended to put the original creditor at a disadvantage. Therefore, when distributing proceeds from other collateral, the original creditor's interest in full satisfaction of their senior claim should not be prejudiced by the surety's partial subrogation. This was a significant clarification, as older interpretations sometimes suggested an equal footing or pro-rata distribution between the creditor and a partially subrogating party. This principle is now expressly codified in the revised Civil Code (Article 502, Paragraph 3, effective from April 2020).

Outcome of the Appeal for X Bank:

While the Supreme Court affirmed the principle that X Bank (as the original creditor) would have priority over the sureties B and C Corp. for the remainder of its first-ranking claim against the Debtor Properties (Point 3), this re-ordering of priorities between X Bank and the sureties for that specific portion of the debt did not ultimately change the amount that Y (the junior mortgagee on the Surety Properties) was entitled to receive. Y's claim was based on the sureties' subrogated right to X Bank's original first-ranking mortgage, and the amount Y could receive was capped by Y's own claim and the extent of the sureties' reimbursement rights. Since the adjustment between X Bank and the sureties regarding the first-ranking mortgage proceeds did not diminish Y's allocation under the "subrogation-like doctrine" (Point 1), the Supreme Court found that X Bank had no practical legal interest (rigai) in objecting to Y's specific distribution as determined by the lower courts' application of that doctrine. Therefore, X Bank's appeal was ultimately dismissed.

Unpacking the "Subrogation-like Doctrine"

The "subrogation-like doctrine" is a judicial creation designed to achieve fairness among junior creditors in complex joint mortgage scenarios involving sureties in rem.

- When a surety's property is sold first to pay a senior joint mortgage, the surety subrogates to the senior mortgagee's lien on the primary debtor's remaining properties.

- This doctrine allows a junior mortgagee whose security was only on the surety's property to "follow" this subrogated lien and claim against the debtor's other properties, with the same priority that the surety acquired (i.e., the original senior mortgagee's priority). This effectively gives the junior mortgagee on the surety's property a chance at recovery from the primary debtor's assets, preventing them from being completely wiped out if the surety's property is exhausted by the senior mortgage.

- This has been supported by many scholars as protecting the surety's own expectation of subrogation from being diluted by subsequent mortgages on the debtor's property. However, it has also been criticized for its complexity and potential perceived unfairness to junior mortgagees who lent directly against the debtor's property, as they find themselves subordinated to a claim derived from a junior mortgage on a different party's (the surety's) property.

Creditor Priority in Partial Subrogation – A Key Development

The Supreme Court's clarification that the original creditor takes priority over a partially subrogating surety when distributing proceeds from commonly secured collateral was a groundbreaking aspect of this judgment. It overturned older case law that sometimes suggested an equal (pro-rata) sharing in such situations. This principle, favoring the full satisfaction of the original creditor before the subrogating party recovers, was seen as better protecting the primary creditor and has since been explicitly incorporated into the revised Japanese Civil Code.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of May 23, 1985, provides vital clarifications on the intricate priority rules governing the foreclosure of joint mortgages that involve properties of both the primary debtor and third-party sureties in rem. It affirmed the judicially developed "subrogation-like doctrine," which allows a junior mortgagee on a surety's property to benefit from the surety's subrogation to the senior mortgage against the debtor's other assets. Simultaneously, it established the important principle that an original creditor retains priority over a partially subrogating surety when proceeds from remaining collateral are distributed. The narrow interpretation of the "non-exercise of subrogation rights" agreement in the context of an ongoing execution by the senior creditor also provides practical guidance. This judgment, particularly its stance on creditor priority in partial subrogation, has had a lasting impact on Japanese security law and influenced subsequent legislative reforms.