Joint Mortgages and Sureties: Protecting Junior Lenders When Senior Mortgage is Partially Released in Japan

Date of Judgment: November 6, 1992

Case Name: Claim for Return of Unjust Enrichment

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

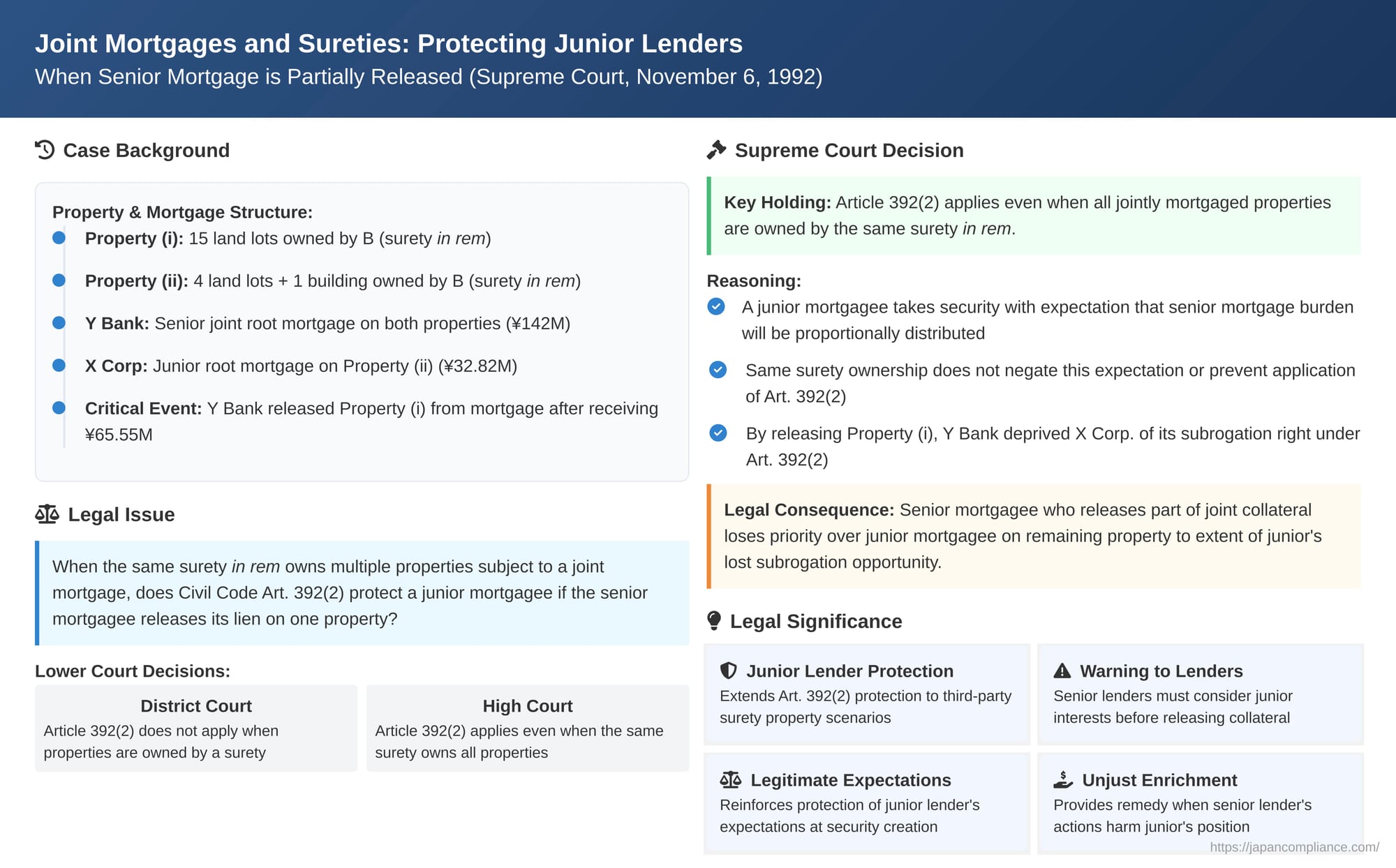

Joint mortgages, where a single debt is secured by mortgages on multiple properties, are common financial tools. These arrangements can become particularly intricate when the properties involved are owned by a third-party "surety in rem" (butsujō hoshōnin) – someone who pledges their own property to secure the debt of another (the primary debtor). Further complexity arises when junior mortgagees also have claims against some, but not all, of these jointly mortgaged properties. A critical question is: if the senior joint mortgagee releases its lien on one of the properties, how does this affect a junior mortgagee whose security is on another of the jointly mortgaged properties, especially when all these properties belong to the same surety in rem? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this precise issue in a significant judgment on November 6, 1992, clarifying the rights of such junior mortgagees.

The Complex Financial Web: Multiple Properties, One Surety, Competing Mortgagees

The case revolved around Y Bank (the senior mortgagee), X Corp. (a junior mortgagee), B (a surety in rem who owned all the relevant properties), and A Corp. (the primary debtor).

- Y Bank's Senior Joint Root Mortgage: Y Bank held a first-ranking joint root mortgage (kyōdō neteitōken) with a maximum credit limit of ¥142 million. This mortgage was established by B, the surety in rem, to secure debts owed by A Corp. to Y Bank. The mortgage covered two distinct sets of properties owned by B:

- Property (i): A collection of 15 lots of land.

- Property (ii): Another collection of 4 lots of land and 1 building.

- X Corp.'s Junior Root Mortgage: X Corp. also held a claim against A Corp. To secure this, B (the same surety in rem) granted X Corp. a root mortgage. Initially, this junior mortgage was on a part of Property (i) (11 of the 15 lots). However, at the request of A Corp. (who wished to sell Property (i) to repay debts), X Corp. agreed to release its mortgage on Property (i). In return, B granted X Corp. a new junior root mortgage with the same maximum amount (¥32.82 million), but this time on Property (ii). This new mortgage on Property (ii) was second in rank to Y Bank's existing senior joint root mortgage on Property (ii). Both mortgages were duly registered.

- Sale of Property (i) and Partial Release by Y Bank: B subsequently sold Property (i) to a third party, C Corp., for over ¥145.31 million. C Corp. completed its ownership registration and carried out development work on Property (i). Following A Corp.'s insolvency, Y Bank, apparently at C Corp.'s behest (as C Corp. would want clear title to Property (i)), agreed to release its senior joint root mortgage lien specifically from Property (i). In consideration for this release, Y Bank received a "substitute payment" (dai-i bensai) of over ¥65.55 million from C Corp., which was applied towards A Corp.'s debt.

- Foreclosure on Property (ii) and Distribution: Y Bank then foreclosed its remaining senior joint root mortgage, now solely on Property (ii). From the auction proceeds of Property (ii), Y Bank received approximately ¥31.02 million towards its outstanding secured claim against A Corp. (which still exceeded ¥68.09 million).

- X Corp. Receives Nothing: Because Y Bank's senior claim absorbed the available proceeds from Property (ii), X Corp., holding the junior mortgage on Property (ii), received no distribution from this auction, despite having an outstanding secured claim against A Corp. of over ¥24.52 million.

- X Corp.'s Lawsuit: X Corp. sued Y Bank, claiming unjust enrichment. X Corp.'s core argument was that if Y Bank had not released its mortgage on Property (i), X Corp., as a junior mortgagee on Property (ii), would have been entitled to exercise a right of subrogation under Article 392, Paragraph 2, second sentence of the Civil Code. This provision allows a junior mortgagee on one property to step into the senior joint mortgagee's shoes and claim against other jointly mortgaged properties under certain conditions. By releasing the mortgage on Property (i), Y Bank had destroyed X Corp.'s potential subrogation target. X Corp. argued that Y Bank should therefore not be able to claim priority over X Corp. from the proceeds of Property (ii) to the extent that X Corp. was harmed by this lost subrogation opportunity. Y Bank's receipt of funds from Property (ii) that should have, in X Corp.'s view, been available to X Corp. (via the subrogation mechanism that Y Bank's actions frustrated) constituted unjust enrichment.

The Legal Question: Does Art. 392(2) Apply When All Jointly Mortgaged Properties Belong to the Same Surety in Rem?

The lower courts had diverged on this critical issue.

- The District Court: Dismissed X Corp.'s claim. It held that Article 392, Paragraph 2, second sentence of the Civil Code (which provides for the junior mortgagee's subrogation) applies only when all the properties under the joint mortgage belong to the primary debtor. Since, in this case, all properties (Property (i) and Property (ii)) belonged to B, a surety in rem, the provision was deemed inapplicable.

- The High Court: Reversed the District Court and ruled substantially in favor of X Corp. It found that the principle of Article 392, Paragraph 2, second sentence could apply even when all properties were owned by the same surety in rem, and that Y Bank's release of the mortgage on Property (i) had indeed harmed X Corp.'s legitimate expectations. Y Bank appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (November 6, 1992): Extending Protection to Junior Mortgagees

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Bank's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision in favor of X Corp. This judgment significantly clarified the application of Article 392, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code in situations involving a single surety in rem owning all jointly mortgaged properties.

- Applicability of Civil Code Article 392(2) to Properties Owned by the Same Surety in Rem:

The Court held that when multiple properties (e.g., Property Alpha and Property Beta) belonging to the same surety in rem* are subject to a senior joint mortgage, and one of these properties (Property Alpha) is also encumbered by a junior mortgage:

If the proceeds from Property Alpha alone are being distributed (e.g., because Property Alpha was sold first, or because the senior mortgage on Property Beta was released), the junior mortgagee on Property Alpha can exercise the right of subrogation provided by Article 392, Paragraph 2, second sentence. This means the junior mortgagee can effectively step into the senior joint mortgagee's position and assert rights against Property Beta, up to the amount that the senior mortgagee could have received from Property Beta if the total secured debt had been apportioned between Property Alpha and Property Beta according to their respective values (as envisaged by Article 392, Paragraph 1).- Rationale: The Supreme Court reasoned that a junior mortgagee, when taking a mortgage on one of several properties (e.g., Property Alpha) already encumbered by a senior joint mortgage, typically does so with the expectation that the burden of the senior mortgage will be distributed proportionally across all the jointly mortgaged properties according to their values. If the senior mortgagee then satisfies its entire claim (or a disproportionate amount) from Property Alpha alone, thereby exhausting the funds available for the junior mortgagee, this harms the junior mortgagee's legitimate expectation of there being some surplus value in Property Alpha. Article 392, Paragraph 2, second sentence is designed to protect this expectation by allowing the junior mortgagee to subrogate to the senior mortgagee's rights against the other jointly mortgaged properties (Property Beta).

The Court found this reasoning applicable even when the same surety in rem owns all the properties. The surety in rem (B, in this case), having granted the junior mortgage on Property Alpha (Property (ii) here) knowing it was part of a larger joint mortgage with Property Beta (Property (i)), is not unfairly prejudiced by allowing the junior mortgagee this subrogation right against the surety's other jointly mortgaged property. The Court noted that the surety's own potential rights of subrogation against the primary debtor (A Corp.) for any loss incurred from Property Alpha being sold are a separate matter and do not negate the junior mortgagee's specific subrogation rights under Article 392(2) concerning the other properties also owned by the surety and included in the senior joint mortgage.

- Rationale: The Supreme Court reasoned that a junior mortgagee, when taking a mortgage on one of several properties (e.g., Property Alpha) already encumbered by a senior joint mortgage, typically does so with the expectation that the burden of the senior mortgage will be distributed proportionally across all the jointly mortgaged properties according to their values. If the senior mortgagee then satisfies its entire claim (or a disproportionate amount) from Property Alpha alone, thereby exhausting the funds available for the junior mortgagee, this harms the junior mortgagee's legitimate expectation of there being some surplus value in Property Alpha. Article 392, Paragraph 2, second sentence is designed to protect this expectation by allowing the junior mortgagee to subrogate to the senior mortgagee's rights against the other jointly mortgaged properties (Property Beta).

- Consequence of the Senior Mortgagee Releasing Its Lien on Another Jointly Mortgaged Property:

Building on this, the Court affirmed the principle that if the senior joint mortgagee (Y Bank) releases its mortgage on one of the properties (Property (i) in this case), which would have been the target for the junior mortgagee's (X Corp.'s) right of subrogation under Article 392(2), then the senior mortgagee loses its priority over the junior mortgagee on the remaining property (Property (ii)) to the extent that the junior mortgagee could have benefited from that subrogation. The Supreme Court cited its earlier precedent (Supreme Court, July 3, 1969, Minshū Vol. 23, No. 8, p. 1297) for this rule. - Unjust Enrichment:

Consequently, if the senior mortgagee, after such a release, receives proceeds from the auction of the remaining property (Property (ii)) that, due to this loss of priority, should have rightfully gone to the junior mortgagee (X Corp.), this constitutes unjust enrichment. The senior mortgagee must then return these funds to the prejudiced junior mortgagee. The Court cited another of its precedents for this conclusion (Supreme Court, March 22, 1991, Minshū Vol. 45, No. 3, p. 322).

Application to the Facts:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found the High Court's decision to be correct. X Corp., as the junior mortgagee on Property (ii), had a legitimate expectation protected by Article 392, Paragraph 2. Y Bank's release of its senior mortgage on Property (i) deprived X Corp. of its ability to subrogate against Property (i). Therefore, Y Bank lost its priority over X Corp. regarding the proceeds from Property (ii) to the extent of X Corp.'s lost subrogation opportunity. Y Bank's collection of these funds from Property (ii) at X Corp.'s expense was an unjust enrichment.

The Junior Mortgagee's "Expectation" as a Key Principle

A recurring theme in this judgment and the related legal commentary is the protection of the junior mortgagee's "expectation." When a junior mortgage is created on a property already subject to a senior joint mortgage, the junior mortgagee assesses the available equity based on the assumption that the senior debt will be satisfied proportionally from all properties included in the joint mortgage. Actions by the senior mortgagee that disrupt this pro-rata satisfaction and concentrate the entire senior debt burden onto the property encumbered by the junior mortgage (or eliminate other avenues for recovery via subrogation) are seen as harming this legitimate expectation. Article 392, Paragraph 2 aims to rectify this.

Impact of Releasing Part of the Joint Collateral

This 1992 judgment serves as a clear warning to senior joint mortgagees. Before releasing their lien on any part of the jointly mortgaged collateral, they must carefully consider the potential impact on junior mortgagees whose security is on other properties within the joint mortgage pool (when all such properties are owned by the same surety in rem). A release that prejudices a junior mortgagee's subrogation rights under Article 392, Paragraph 2 can lead to the senior mortgagee losing part of their priority claim on the remaining collateral.

Distinction from Debtor/Surety Property Combinations

It's important to distinguish this case from situations where the jointly mortgaged properties are owned by a combination of the primary debtor and a surety in rem (as was the scenario in the M91 case, Supreme Court, May 23, 1985). In those debtor-surety scenarios, the surety's own right of subrogation against the debtor under Article 501 of the Civil Code often takes precedence in determining priorities, and Article 392(2) might not apply directly in the same way. The present case (M92) is distinct because the same surety in rem* owned all the properties involved in the senior joint mortgage. In this specific context, the surety's "internal" subrogation over their own other property is not seen as a barrier to the direct application of Article 392(2) for the benefit of a junior mortgagee on one of those properties.

Potential Influence of 2017 Civil Code Reforms (Article 504)

While Article 392 itself was not amended in the major 2017 Civil Code (law of obligations) reforms, Article 504, which deals with the creditor's duty to preserve security in the context of subrogation by a paying party (like a guarantor or surety in rem), was revised. The amended Article 504, Paragraph 2 now provides that a subrogating party is not discharged from their obligation (and thus the creditor does not lose rights) if the creditor lost or diminished the security for a "commercially reasonable cause."

Legal commentators suggest that the spirit of this amendment—protecting a creditor who acts reasonably in managing security—might, by analogy, influence the interpretation of the "loss of priority" rule discussed in the 1992 judgment. If a senior joint mortgagee releases their lien on one property for what is deemed a "commercially reasonable cause" (e.g., to facilitate a partial sale that is beneficial for overall debt recovery or minimizes greater losses), it is an open question whether they would still automatically lose priority against a junior mortgagee on the remaining property to the same extent as held in 1992. This could mean that the circumstances under which a senior mortgagee is penalized for releasing part of their joint collateral might become more nuanced, depending on the reasonableness of their actions.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of November 6, 1992, represents a significant development in the law of joint mortgages in Japan, particularly by extending the protective subrogation rights of junior mortgagees under Civil Code Article 392, Paragraph 2 to situations where all properties under a senior joint mortgage are owned by the same surety in rem. This decision underscores the importance of a junior mortgagee's expectation of proportional burden-sharing by the senior mortgage across all collateral. It also serves as a critical reminder to senior joint mortgagees that releasing their lien on a portion of the collateral can have direct adverse consequences on their priority over junior mortgagees concerning the remaining collateral if such a release prejudices the junior lienholder's statutory subrogation rights. The ruling reinforces the need for careful consideration of the entire collateral structure and the rights of all secured parties when administering joint mortgages.