Jockeying for Position: When a Creditor's Subrogation Suit Meets a Tax Authority's Collection Suit – A 1970 Japanese Supreme Court Case

Date of Judgment: June 2, 1970

Case Name: Real Estate Sale Price Claim Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: 1969 (O) No. 626

Introduction

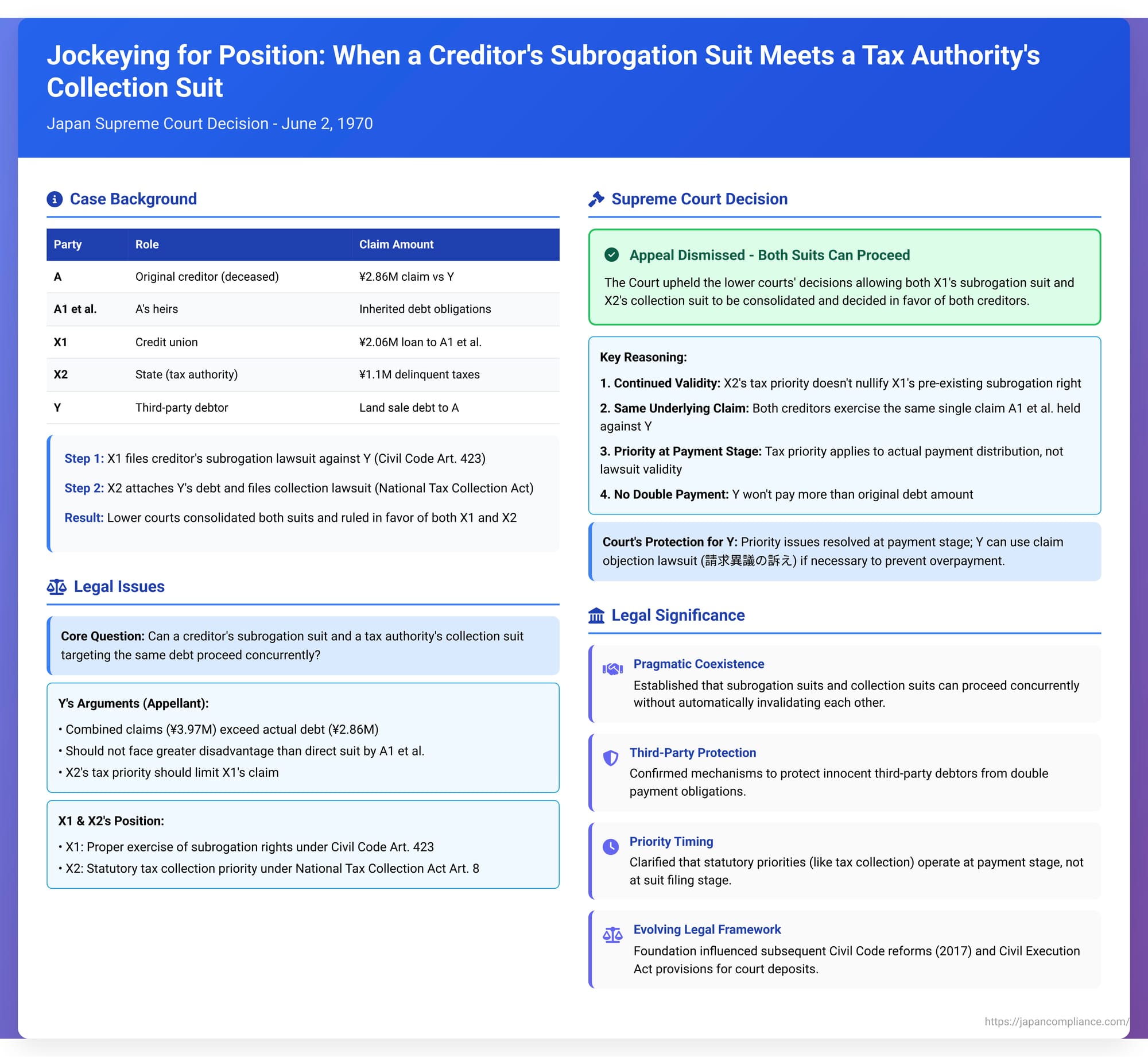

Imagine a debtor (A) owes money to multiple creditors. A also happens to be a creditor to a third party (Y). One of A's creditors (X1) might try to recover their debt by stepping into A's shoes and suing Y directly – a process known as a "creditor's subrogation lawsuit." While this suit is ongoing, another powerful creditor, such as the State (X2) seeking to collect unpaid taxes, might attach the same debt Y owes to A and initiate its own "collection lawsuit" against Y. How should the courts handle such a scenario where two different creditors are pursuing the same underlying claim against the same third-party debtor, using different legal mechanisms?

This complex interplay of creditor actions was the subject of a Japanese Supreme Court decision on June 2, 1970. The ruling provided guidance on the permissibility of such concurrent lawsuits and the protection of the third-party debtor caught in the middle.

The Factual Tangle: A Credit Union, the State, and a Disputed Land Sale Debt

The key players and events were:

- A (Original Creditor, Deceased): Had a claim for JPY 2.86 million (plus some overdue interest) against Y, arising from a land sale.

- A1 et al. (A's Heirs): Inherited A's assets and liabilities.

- Y (Defendant/Appellant): The alleged debtor of A for the land sale price.

- X1 (Plaintiff 1/Respondent): A credit union, to whom A (and subsequently A1 et al.) owed JPY 2.06 million on a loan.

- X2 (Plaintiff 2/Respondent): The State of Japan, to whom A1 et al. owed JPY 1.1 million in delinquent income tax.

The sequence of legal actions:

- X1's Subrogation Lawsuit: When A1 et al. failed to repay the loan, X1 initiated a "creditor's subrogation lawsuit" (債権者代位訴訟, saikensha daii soshō) against Y. Under this doctrine (Civil Code Art. 423), a creditor can exercise a right belonging to their debtor if the debtor neglects to exercise it, and such exercise is necessary to preserve the creditor's own claim. X1 sued Y for payment of the land sale price owed to A1 et al., up to the amount of X1's loan claim (JPY 2.06 million).

- X2's Attachment and Collection Lawsuit: While X1's subrogation suit was pending in the first instance court, X2 (the State) took action to collect the delinquent taxes. X2 attached the land sale price claim that A1 et al. held against Y, utilizing procedures under the National Tax Collection Act (国税徴収法). Following the attachment, X2 filed its own "collection lawsuit" (取立訴訟, toritate soshō) against Y, seeking payment of JPY 1.91 million (presumably the tax claim plus penalties or interest).

- Consolidation and Y's Defense: The first instance court consolidated X1's and X2's lawsuits for joint hearing. Y, the defendant, primarily disputed the existence of the underlying land sale debt to A. Alternatively, Y argued that if the debt did exist, X1's claim should be reduced to the extent that X2's tax claim had priority. In its appeal to the Supreme Court, Y emphasized that it should not be placed in a more disadvantageous position than if A1 et al. had sued directly. Y pointed out that the lower courts had ordered Y to pay sums to X1 and X2 which, when combined (JPY 2.06 million to X1 and JPY 1.91 million to X2, totaling JPY 3.97 million in principal alone), exceeded Y's alleged total debt to A1 et al. (JPY 2.86 million). Y argued this constituted an impermissible overreach of the creditors' rights.

The lower courts (Kagoshima District Court and Fukuoka High Court, Miyazaki Branch) had ruled in favor of both X1 and X2, ordering Y to pay them their respective claimed amounts. They considered the two lawsuits to be in a relationship akin to "quasi-mandatorily joined litigation" (類似必要的共同訴訟). They also held that X2's statutory priority for tax claims (National Tax Collection Act Art. 8) meant priority in actual payment from the attached funds, but it did not strip X1 of its right to pursue its subrogation suit, nor did it render X1's claim unfounded.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Both Suits Can Proceed

The Supreme Court, on June 2, 1970, dismissed Y's appeal. It affirmed the lower courts' decisions, allowing both X1's subrogation suit and X2's collection suit to proceed and be upheld.

The Court reasoned:

- Continued Validity of X1's Subrogation Suit: X1 was pursuing its loan claim by stepping into the shoes of A1 et al. to collect the land sale price from Y. The priority granted to national tax collection under Article 8 of the National Tax Collection Act needs only to be secured at the stage of actual payment. Therefore, even if the State (X2) subsequently initiates tax delinquency proceedings, attaches the same claim, and files its own collection lawsuit, a pre-existing subrogation suit by another creditor (X1) concerning the same claim does not become impermissible. X1 does not lose its authority to exercise its subrogation right.

- Court's Power to Consolidate and Uphold Both Claims: It is permissible for the court to consolidate both X1's and X2's claims for hearing and to rule in favor of both.

- No Undue Prejudice to Y (Third-Party Debtor): The Court addressed Y's concern about being forced to pay more than its debt. It stated that X1 and X2 were essentially exercising the same single claim that A1 et al. had against Y, albeit through their respective legal authorities (subrogation for X1, tax collection for X2). Therefore, even if judgments were issued in favor of both X1 and X2, Y would not be compelled to make actual payments exceeding the amount of its original debt to A1 et al. Y's argument that it would suffer undue prejudice was dismissed.

Why Can Both Suits Coexist? The Evolving Legal Landscape

The Supreme Court did not provide extensive reasoning for why X1's suit remained valid beyond stating that X2's tax priority didn't nullify it. This has led to academic discussion about the underlying legal theory.

Prevailing Interpretation at the Time (The "Private Attachment" Theory of Subrogation):

Many scholars in 1970 interpreted the Court's conclusion as viewing the subrogation suit and the collection suit as analogous to two competing collection suits. This interpretation was often linked to a 1939 Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation) precedent which held that once a subrogating creditor commences their action (and the debtor is notified or becomes aware), the debtor loses the right to dispose of the subrogated claim. This was often characterized as the subrogating creditor effecting a "private attachment" of the claim, thus putting the subrogating creditor (like X1) on a somewhat similar footing to an attaching creditor (like X2).

A Counter-Argument (Subrogation vs. Debtor's Own Suit):

An opposing view at the time argued that a subrogating creditor, who might not even possess an enforceable judgment against their own debtor (A1 et al.), should not be equated with an attaching creditor, who typically does (or, in the case of tax authorities, has equivalent statutory power). These scholars suggested the situation was more analogous to a debtor's own lawsuit for performance competing with an attaching creditor's collection suit. They pointed to another Daishin-in precedent (from 1929) which held that if a claim currently in litigation was attached by a creditor of the plaintiff, the plaintiff-debtor could no longer maintain their performance suit. By this logic, X1's subrogation suit should also have become impermissible once X2 attached the claim.

Impact of Subsequent Legal Developments:

The legal landscape has evolved since 1970:

- Weakening of the "Private Attachment" Theory: Article 423-5 of the current Civil Code (introduced in the major 2017 reforms, but reflecting evolving interpretations) explicitly states that the debtor does not lose the right to dispose of the subrogated claim merely because their creditor has initiated a subrogation action. This significantly undermines the "private attachment" analogy and the basis for easily equating subrogating creditors with attaching creditors. Consequently, the opposing view comparing the subrogation/collection scenario to a debtor's suit/collection scenario might seem more fitting today.

- Debtor's Right to Sue Despite Attachment Affirmed: Crucially, the 1929 Daishin-in precedent (which suggested a debtor loses standing if the claim is attached) was overruled by the Supreme Court in a 1973 decision (the "e53" case previously discussed). The 1973 ruling established that even if a claim is provisionally attached, the debtor (the original plaintiff) does not lose their standing to pursue a performance lawsuit. This principle appears to extend to full attachments as well, based on a 1980 Supreme Court case. This development means that even if X1's subrogation suit is seen as analogous to A1 et al. suing directly, the attachment by X2 would not automatically render X1's suit impermissible.

- Interest of Subrogating Creditor: Under the current Civil Execution Act (Art. 154), creditors who do not possess an enforceable title generally cannot make a demand for distribution from attached funds. This makes the ability of a subrogating creditor (who may not have a judgment against their own debtor when they file the subrogation suit) to maintain their own lawsuit quite significant.

These subsequent developments suggest that the 1970 Supreme Court's conclusion—that X1's subrogation suit could continue—remains supportable, even if the original theoretical underpinnings (like the "private attachment" idea) have been modified by later law.

Procedural Complexities: Joinder, Duplicate Litigation, and Judgments

The 1970 decision accepted that X2's later collection suit was valid and that both lawsuits could be consolidated. However, this raises procedural questions:

- Risk of Conflicting Judgments and Duplicate Litigation (CCP Art. 142): If judgments in both X1's subrogation suit and X2's collection suit were considered binding on the original debtors (A1 et al.)—as was the prevailing theory at the time for both types of suits—allowing two parallel lawsuits could lead to contradictory outcomes concerning A1 et al.'s rights and liabilities. This appears to conflict with the purpose of Article 142 of the Code of Civil Procedure, which prohibits duplicate litigation, partly to avoid such contradictory judgments.

- The Case Investigator's Perspective: The judicial research official for the 1970 Supreme Court case reportedly suggested that X2 filing a separate collection suit was technically improper. Instead, X2 should have sought to intervene in X1's ongoing subrogation suit as a co-plaintiff (under then CCP Art. 52, now Art. 47 regarding independent party intervention, or Art. 52 regarding joinder as co-plaintiff). The consolidation of the two lawsuits by the first instance court was seen as a way to cure this procedural defect. If this view is taken, the consolidated proceeding would indeed be "quasi-mandatorily joined litigation," where the claims must be decided uniformly for all parties involved, as the first instance court had held.

Current Theories and Their Impact:

The understanding of these procedural issues has also evolved:

- Binding Effect of Collection Suit Judgments: The prevailing view today tends to deny that a judgment in a collection lawsuit (like X2's against Y) automatically binds the original debtor (A1 et al.) regarding the existence or amount of the attached claim. If this is correct, then X2's subsequent collection suit would not necessarily be dismissed under CCP Art. 142 solely on the grounds of avoiding conflicting judgments against A1 et al. (though Art. 142 also serves other purposes like procedural economy).

- Propriety of Joinder/Intervention: If X2's judgment against Y doesn't bind A1 et al. (and thus wouldn't bind X1 who is suing in A1 et al.'s stead), then the rationale for X2 having to mandatorily join X1's suit, or for the suits requiring a single, unified resolution for all, becomes less clear. The consolidated suits might simply be treated as an ordinary joinder of claims if the strict requirements for mandatory joinder are not met.

- Binding Effect of Subrogation Suit Judgments: While the reformed Civil Code generally maintains that a judgment in a subrogation suit (like X1's against Y) is binding on the debtor (A1 et al.), this doesn't preclude all debate on the nuances.

The PDF commentary concludes that while the 1970 Supreme Court's practical outcome—allowing the consolidated hearing of both claims—is likely still valid today, the precise procedural classification (e.g., permissibility of a separate later suit versus mandatory intervention, the exact type of joinder involved) remains somewhat opaque and subject to theoretical debate.

Protecting the Third-Party Debtor (Y)

A key concern for Y was being forced to pay more than its actual debt to A1 et al. The Supreme Court asserted this would not happen, as X2's tax priority would be handled at the actual payment stage.

- How Y Avoids Double Payment: Y can prevent X1 (the subrogating creditor) from enforcing its judgment to the point of actual collection by highlighting X2's attachment and its statutory priority (especially for tax claims). If, after Y pays X2, X1 still attempts to enforce an excessive amount, Y can file a claim objection lawsuit (請求異議の訴え, seikyū igi no uttae) to stop further execution by X1. This ensures X2's priority is respected and Y does not pay twice on the same underlying debt.

- The Burden on Y: Critics of this approach point out that it places a procedural burden on Y—an arguably innocent third party caught in a dispute between A1 et al. and their creditors—to actively manage these competing claims and take legal steps to avoid overpayment. Some scholars argued at the time that the judgment in favor of X1 should have been made conditional upon X2's tax attachment being lifted or satisfied, or that X2's claim should be fully recognized first and X1's claim adjusted accordingly in the judgment itself.

- A Modern Solution for Y: Deposit with the Court: Current law (Civil Execution Act Art. 156(1)) provides a clearer path for the third-party debtor in such situations. Y would now generally have the option to deposit the disputed amount with the court, thereby discharging its liability and leaving it to the competing claimants (X1 and X2) to resolve their priorities in the court's distribution procedure. This issue of protecting the third-party debtor mirrors concerns in cases where a debtor's own performance lawsuit competes with an attaching creditor's collection suit (as seen in the "e53" case).

Conclusion: Pragmatism in the Face of Competing Claims

The Supreme Court's 1970 decision adopted a pragmatic approach, allowing both a pre-existing creditor's subrogation lawsuit and a subsequent tax collection lawsuit concerning the same debt to proceed concurrently. It aimed to ensure that the tax authority's priority could be effected at the payment stage without prematurely derailing the subrogating creditor's efforts to secure their claim. While the theoretical underpinnings of this approach have been debated and refined by subsequent legal developments, particularly regarding the nature of subrogation rights and the binding effect of judgments, the core outcome of allowing consolidated consideration of such competing claims likely remains valid. The evolution of procedural law, especially the enhanced ability for third-party debtors to deposit funds with the court, has further helped to mitigate the burdens placed on parties like Y, who find themselves caught between a debtor and multiple competing creditors.