Job Scope Limitations ("Job-Type" Employment) and Employee Transfers (Hai-ten) in Japan: Defining Boundaries

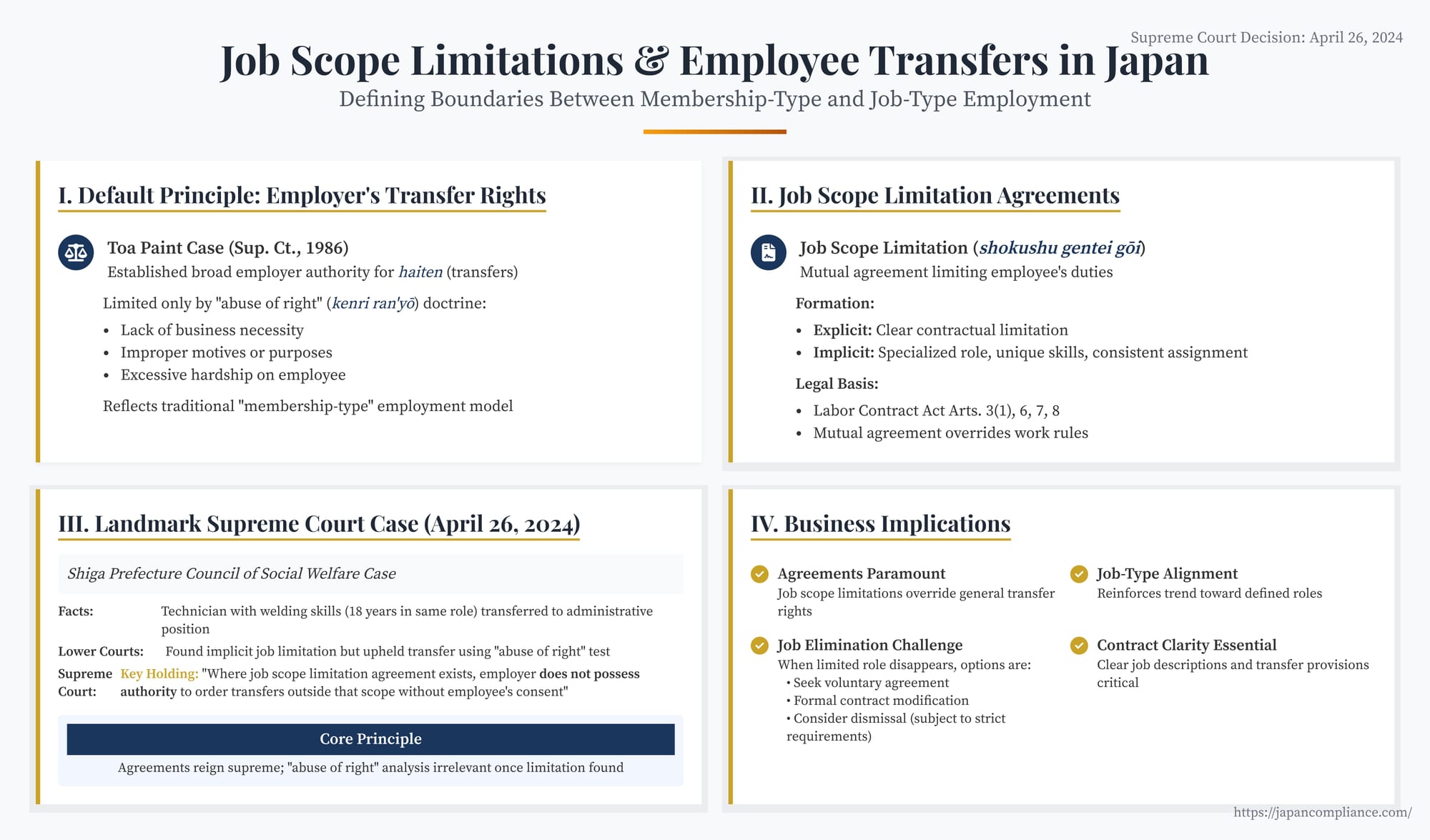

TL;DR: Japan’s Supreme Court (Shiga Prefecture Council of Social Welfare, 2024) ruled that any explicit or implicit agreement limiting an employee’s job scope bars employers from ordering transfers outside that scope without consent—regardless of business necessity. The decision cements job-type principles and forces companies to rethink how they draft contracts and handle role elimination.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Membership vs. Job-Type Employment in Japan

- The Default Principle: Employer’s Broad Right to Order Transfers

- The Crucial Exception: Job Scope Limitation Agreements

- The Shiga Prefecture Council of Social Welfare Case (2024)

- Implications for Business and HR Management in Japan

- Conclusion: Defining Boundaries in Employment

Introduction: Membership vs. Job-Type Employment in Japan

Japan's traditional employment system is often characterized as "membership-type" (メンバーシップ型 - menbāshippu-gata). In this model, employees are hired into the company as a whole, typically directly from school, with the expectation of long-term employment, seniority-based wages, and broad internal mobility. Employers historically enjoyed significant discretion to assign tasks and order transfers (配置転換 - haichi tenkan, often shortened to haiten), encompassing both relocation to different workplaces and changes in job duties, based on business needs.

However, recent years have seen increasing discussion and partial adoption of "job-type" (ジョブ型 - jobu-gata) employment principles. This model emphasizes hiring individuals for specific roles with clearly defined duties and responsibilities, often detailed in job descriptions. This shift aligns with global trends and aims to enhance specialization, attract mid-career talent, and provide greater clarity in roles and evaluations.

A critical legal question arising at the intersection of these models concerns the employer's right to order transfers when an employee's job scope appears to be limited, either explicitly by contract or implicitly through practice. Can an employer unilaterally transfer an employee hired for a specific technical role to a completely different administrative position, especially if the original role diminishes or disappears? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this fundamental question head-on in a significant ruling, the Shiga Prefecture Council of Social Welfare case (Sup. Ct., Second Petty Bench, April 26, Reiwa 6 [2024]), providing crucial clarification on the legal boundaries of job scope limitations and transfer orders.

The Default Principle: Employer's Broad Right to Order Transfers

Under established Japanese labor law precedent, epitomized by the landmark Toa Paint case (Sup. Ct., Jul 14, Showa 61 [1986]), employers generally possess a broad right to order employees to transfer to different locations or change job duties. This right is considered an inherent part of the employer's personnel management authority derived from the employment contract, especially when work rules (shūgyō kisoku) contain clauses permitting transfers based on business necessity.

This broad right is not absolute, however. The Toa Paint doctrine establishes limits based on the principle of "abuse of right" (権利濫用 - kenri ran'yō). A transfer order can be deemed an invalid abuse of the employer's right if:

- It lacks business necessity (業務上の必要性 - gyōmujō no hitsuyōsei). (Though courts tend to find necessity relatively easily unless the transfer is clearly arbitrary).

- It is based on improper motives or purposes (不当な動機・目的 - futō na dōki/mokuteki) (e.g., harassment, forcing resignation).

- It imposes hardship on the employee that significantly exceeds the level they should normally tolerate in the course of employment (通常甘受すべき程度を著しく超える不利益 - tsūjō kanju subeki teido o ichijirushiku koeru furieki), considering factors like impact on family life, health, and career, compared to the business necessity.

Unless one of these "abuse of right" conditions is met, transfer orders have traditionally been upheld, reflecting the flexibility inherent in the membership-type model.

The Crucial Exception: Job Scope Limitation Agreements (職種限定合意 - Shokushu Gentei Gōi)

The established framework changes significantly if there is an agreement between the employer and employee limiting the scope of the employee's job (職種 - shokushu) or duties (業務内容 - gyōmu naiyō). Such an agreement, whether explicit in the contract or implicitly formed through hiring circumstances and long-term practice, creates a specific exception to the employer's general transfer authority.

- How Limitations Arise:

- Explicit Agreement: The employment contract clearly states the employee is hired for a specific role (e.g., "Software Engineer," "Accountant," "Welding Technician") and limits duties to that scope.

- Implicit Agreement: While courts have historically been cautious, an implicit agreement might be inferred based on factors like:

- Recruitment specifically for a position requiring high specialization or qualifications (e.g., doctors, lawyers, pilots, specialized technicians).

- The employee possessing unique skills essential for a particular role that formed the basis of their hiring.

- Consistent assignment to the same specialized role for a very long duration without any indication of broader duties or potential transfers.

- Legal Basis: The Labor Contract Act emphasizes mutual agreement as the foundation of the employment relationship (LCA Art. 3, Para. 1; Art. 6). Specific agreements, including those limiting job scope, generally override conflicting general provisions in work rules (LCA Art. 7, proviso; Art. 8).

The key legal question addressed by the Supreme Court was: what is the precise legal effect of such a job scope limitation agreement on the employer's right to order a transfer outside that agreed scope?

The Shiga Prefecture Council of Social Welfare Case (Sup. Ct., Apr 26, 2024)

Case Background

- The Employee (X): Hired in Heisei 13 (2001) by a foundation (later merged into Y, the Council of Social Welfare) specifically as a technician possessing welding skills, tasked with customizing and developing welfare equipment at a dedicated center.

- Long-Term Role: X worked exclusively in this technical role for 18 years and was the only technician at the center capable of welding.

- Changing Circumstances: From around Heisei 23 (2011), demand for customized equipment significantly decreased. By Reiwa 2 (2020), non-sewing customization work (X's specialty) had dwindled to almost zero.

- The Transfer Order (Y): In March of Heisei 31 (2019), citing the decline in technical work and the need to fill a vacancy in general affairs due to another employee's retirement, Y ordered X to transfer to a non-technical "Facility Management" role involving tasks like visitor reception and building security, without prior consultation or X's consent.

- The Challenge: X, supported by his labor union, challenged the transfer order, arguing it violated an implicit agreement limiting his job scope to technical work.

Lower Court Rulings (District & High Court)

Both the Kyoto District Court (ruling in Reiwa 4 [2022]) and the Osaka High Court (ruling in Reiwa 4 [2022]) made a crucial two-part finding:

- Implicit Agreement Found: They agreed with X that, based on the hiring circumstances (recruited for specific skills), his unique technical abilities (welding), and his continuous 18-year assignment to the specialized role, an implicit agreement limiting his job scope to technical work related to welfare equipment existed between X and Y.

- Transfer Upheld via Abuse of Right Test: Despite finding the limitation agreement, both courts then proceeded to apply the Toa Paint "abuse of right" framework. They reasoned that:

- There was business necessity for the transfer because X's original technical job had effectively disappeared due to lack of demand, and there was a genuine vacancy in the general affairs section. Transferring X was a reasonable measure to avoid dismissing him.

- The transfer did not impose excessive hardship on X, as the new facility management duties were not overly burdensome.

- Therefore, even though a limitation agreement existed, the transfer order was not an abuse of right and was thus valid.

The Supreme Court's Reversal

The Supreme Court fundamentally disagreed with the lower courts' approach and overturned their decision. Its reasoning established a clear hierarchy between specific agreements and general employer rights:

- Effect of Job Scope Limitation Agreement: The Court stated unambiguously: "Where an agreement exists between an employee and employer limiting the employee's job type or duties to specific ones, the employer does not possess the authority to order the employee to be transferred in violation of said agreement without the employee's individual consent." (判旨Ⅰ1).

- Abuse of Right Analysis is Inapplicable: Because the existence of the limitation agreement meant the employer "did not possess the authority to order the... transfer in the first place" (判旨Ⅰ2), the subsequent question of whether the order constituted an "abuse of right" (considering business necessity or hardship) becomes legally irrelevant. The lower courts erred by applying the abuse of right test after acknowledging the limitation agreement.

- Consent is Key: The only way an employer can validly transfer an employee outside an agreed limited job scope is by obtaining the employee's individual consent to modify the terms of their employment contract (consistent with LCA Art. 8).

- Job Elimination Doesn't Create Transfer Right: The Court implicitly rejected the lower courts' rationale that eliminating the original job created a business necessity justifying the transfer despite the agreement. The elimination of the agreed-upon job simply means the employer can no longer fulfill its contractual obligation to provide that specific work; it doesn't automatically grant a right to assign entirely different work.

The Supreme Court remanded the case, instructing the High Court to proceed based on the principle that if the job scope limitation agreement was indeed found to exist (which the Supreme Court did not overturn as a finding of fact), the transfer order was per se invalid due to the employer's lack of authority, regardless of business necessity or hardship. The High Court would then need to consider remedies, such as damages for the unlawful transfer order.

Implications for Business and HR Management in Japan

This Supreme Court decision carries significant weight for human resource management and employment relations in Japan:

- Agreements Reign Supreme: The ruling powerfully reinforces the principle of mutual consent in Japanese labor contracts. Specific agreements limiting job scope, whether explicit or implicitly formed, are legally binding and override general clauses in work rules or assumptions about employer transfer discretion.

- Rethinking Transfers for Specialists: Companies must exercise greater caution when transferring employees hired for or consistently assigned to highly specialized roles. Relying on broad "business necessity" justifications may be insufficient if a court later finds an implicit job scope limitation existed. The focus shifts from justifying the transfer to justifying the absence of a limiting agreement or obtaining consent for the change.

- Alignment with "Job-Type" Principles: The decision provides strong legal backing for the core concept of job-type employment – that employees are engaged for specific roles and duties. As companies adopt more job-type elements, this ruling clarifies that moving employees outside their defined scope requires consent or formal contract modification, not just a unilateral transfer order.

- Handling Job Elimination: This is perhaps the most critical implication. When a specific, limited job scope is eliminated due to restructuring, automation, or lack of demand, the employer cannot simply transfer the employee to an unrelated position based on business need if a limitation agreement covering the original scope exists. The employer's options become:

- Seek the employee's voluntary agreement to transfer to a different role (potentially with retraining or adjusted terms).

- Formally propose a modification of the employment contract (requiring consent under LCA Art. 8).

- If no suitable alternative role exists or the employee does not consent, consider dismissal. This would likely be framed as a redundancy/economic dismissal (整理解雇 - seiri kaiko), which itself is subject to very strict legal requirements in Japan (necessity of reduction, exhaustion of alternatives, fairness of selection, procedural fairness). The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the idea that the transfer was justified simply to avoid dismissal.

- Importance of Clarity in Contracts and Hiring:

- Employment contracts and job descriptions for specialized roles should be drafted with careful attention to defining the scope of duties and explicitly addressing the possibility (or limitation) of future transfers or changes in duties. Ambiguity may be interpreted in favor of an implicit limitation.

- Hiring processes for specialists should clearly communicate the nature of the role and any expectations regarding potential future changes in responsibilities.

Conclusion: Defining Boundaries in Employment

The Supreme Court's ruling in the Shiga Prefecture Council of Social Welfare case marks a pivotal moment in Japanese labor law concerning employee transfers and job scope. It firmly establishes the principle that an agreement limiting an employee's job scope, whether express or implied, negates the employer's unilateral right to order transfers outside that scope. In such cases, the traditional "abuse of right" analysis regarding business necessity and employee hardship is bypassed; the order is simply unauthorized without employee consent.

This decision clarifies the legal boundaries, strengthening the position of employees hired for specific roles, particularly specialists, and aligning Japanese law more closely with job-type employment principles. For businesses, it underscores the critical importance of respecting contractual agreements and obtaining explicit consent for significant changes in job duties, even when faced with business restructuring or the elimination of specific roles. Navigating this requires careful contract drafting, transparent communication during hiring, and a shift away from assuming unlimited transfer discretion, especially for specialized positions within the workforce.

- Mind the Gap: Wage Disparity Between Fixed-Term and Indefinite-Term Employees

- Employee Dismissals in Japan: Membership vs. Job-Based Models

- Freedom to Resign vs. Training-Cost Clawbacks in Japan

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — Q&A on Job-Type Employment and Transfers (JP)

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/koyou_roudou/roudoukijun/job-type.html