Job-Scope Agreements & Employee Transfers in Japan: When Contract Limits Override Employer Flexibility

TL;DR

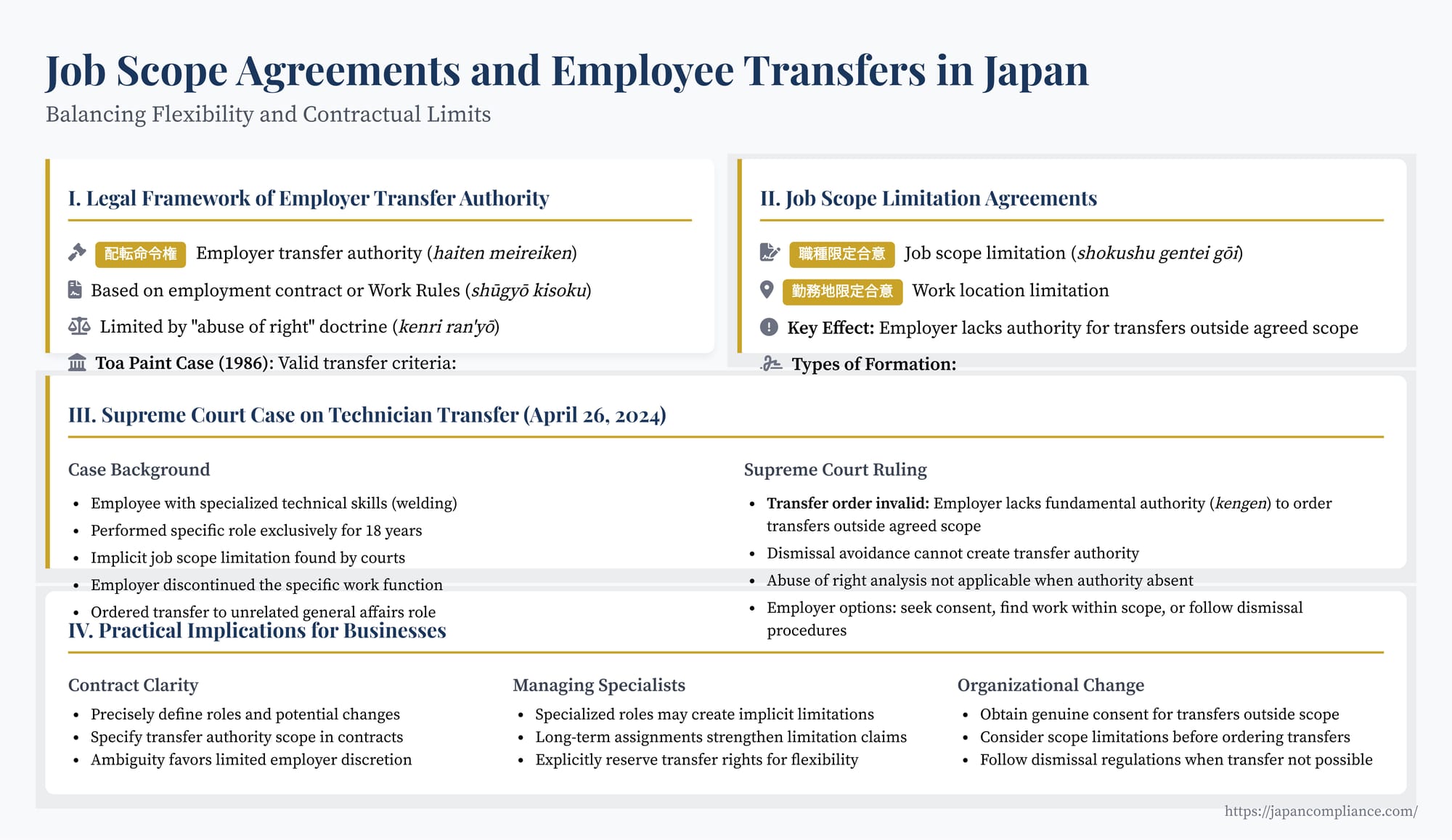

- A 2024 Supreme Court ruling confirms that explicit or implicit job-scope or location limits override an employer’s general transfer right.

- If such an agreement exists, the employer lacks authority to order an out-of-scope transfer unless the employee consents.

- Employers must craft clear contracts, seek genuine consent, or follow proper dismissal procedures when specialised roles disappear.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Balancing Business Needs and Employee Expectations

- Employer's Authority to Order Transfers

- The Crucial Exception: Job Scope Limitation Agreements

- Case Study: The Technician Transfer (Supreme Court, Apr 26 2024)

- Analysis and Implications for Employers

- Conclusion: Defining Roles and Respecting Agreements

Introduction: Balancing Business Needs and Employee Expectations

Managing workforce deployment is a critical function for any business. Employers often seek flexibility to assign employees to different roles, tasks, or locations (a practice known as 配置転換, haichi tenkan, or simply 配転, haiten in Japanese) to meet evolving operational needs, facilitate employee development, or respond to organizational changes. However, employees, particularly those hired for specialized skills or with specific location requirements, often seek stability and roles that align with their expertise and expectations set at the time of hiring. This inherent tension between employer flexibility and employee expectations frequently leads to disputes over the validity of transfer orders.

Traditionally, Japanese employment practices, especially concerning regular, full-time employees (seishain, 正社員) hired under the assumption of long-term employment, often granted employers broad discretion regarding transfers. This was seen as part of the implicit understanding that employees would serve the company's needs in various capacities over their careers.

However, this broad discretion is not absolute. It can be significantly constrained by specific agreements between the employer and employee that limit the scope of the employee's job duties (職種限定, shokushu gentei) or restrict their work location (勤務地限定, kinmuchi gentei). The legal effect of such limiting agreements, particularly when an employer seeks to transfer an employee whose original role has become redundant, was recently clarified by a key Supreme Court of Japan decision. This ruling underscores the primacy of contractual agreements in defining the employment relationship and sets important boundaries on employer authority.

This article explores the legal framework governing employee transfers in Japan, the impact of job scope limitation agreements, and analyzes the implications of the Supreme Court's decision of April 26, 2024, for businesses managing their workforce.

Employer's Authority to Order Transfers (配転命令権, Haiten Meireiken)

In the absence of specific contractual limitations, Japanese employers generally possess the authority to order employee transfers under certain conditions. This authority (配転命令権, haiten meireiken) is not explicitly granted by statute for private sector employment but is judicially recognized based on the following:

- Contractual or Work Rules Basis: The authority typically stems from provisions in the individual employment contract or, more commonly, in the company's Work Rules (就業規則, shūgyō kisoku) that state the employer may order transfers for business reasons. Most comprehensive Work Rules in Japan contain such clauses.

- Business Necessity: The transfer must be based on genuine operational needs, such as filling vacancies, balancing workloads, developing employee skills, launching new projects, or responding to organizational restructuring.

- Judicial Recognition: Courts have long recognized this authority, provided it is grounded in the contract or Work Rules and exercised reasonably.

Limits: The Abuse of Right Doctrine

Even when an employer possesses the general authority to order transfers, the exercise of this right is subject to judicial review under the "abuse of right" doctrine (権利濫用, kenri ran'yō), implicitly rooted in the Labor Contract Act. The landmark Toa Paint case (Supreme Court, July 14, 1986) established the key criteria for assessing whether a transfer order constitutes an abuse of the employer's right:

- Lack of Business Necessity: If the transfer serves no genuine business purpose and appears unrelated to operational needs, it may be deemed an abuse.

- Improper Motive: If the transfer is motivated by discriminatory reasons, retaliation, harassment, or an intent to coerce the employee into resigning, it is unlawful.

- Excessive Disadvantage: Even if business necessity exists, the transfer order may be an abuse of right if the disadvantage imposed on the employee (considering impacts on their work, family life, health, finances, etc.) is significantly disproportionate to the employer's operational need. This involves a balancing test.

If a transfer order is found to be an abuse of right, it is deemed legally invalid.

The Crucial Exception: Job Scope Limitation Agreements (職種限定合意)

The general authority of an employer to order transfers can be significantly curtailed or eliminated entirely if there is a mutual agreement between the employer and employee limiting the scope of the employee's job duties or work location.

Concept and Effect

A job scope limitation agreement (職種限定合意, shokushu gentei gōi) establishes an understanding that the employee is hired for, and expected to perform, only a specific type of work, occupy a particular role, or practice a defined profession within the company. Similarly, a work location limitation agreement (勤務地限定合意, kinmuchi gentei gōi) restricts the employee's place of work to a specific geographic area or facility.

The critical legal effect, reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in its April 2024 decision, is that where such a limiting agreement exists, the employer inherently lacks the contractual authority (権限, kengen) to unilaterally order the employee to perform duties or work in a location outside the agreed scope. This principle stems from basic contract law and the Labor Contract Act (Art. 7), which generally provides that individual employment contract terms prevail over conflicting Work Rules provisions if the contract terms are more favorable to the employee. A specific agreement limiting job scope is considered more favorable than a general Work Rules clause permitting broad transfers.

Therefore, if a valid scope limitation exists, ordering a transfer outside that scope is not merely a potentially abusive exercise of authority; it is an act undertaken without any authority in the first place, unless the employee specifically consents to the change.

Formation: Explicit vs. Implicit Agreements

These limiting agreements can be formed in two ways:

- Explicit Agreement: Clearly stated in the written employment contract, offer letter, or a subsequent formal agreement (e.g., "The Employee shall perform duties solely as a [Specific Role] located at the Tokyo office").

- Implicit Agreement (黙示の合意, mokuji no gōi): Inferred from the circumstances surrounding the employment relationship. Establishing an implicit agreement requires demonstrating a clear, mutual understanding, often based on factors like:

- The recruitment process (e.g., hiring through advertisements for a highly specialized position requiring specific qualifications).

- The employee possessing unique, specialized skills or licenses essential for a particular role.

- Long-term assignment to the same specific job duties without any history of transfers to different roles.

- Significantly different working conditions or compensation compared to employees with broader job scopes.

Historically, Japanese courts have been relatively cautious about finding implicit job scope limitations, especially for seishain presumed to have accepted broader mobility as part of their career track. A high evidentiary standard was often required to overcome the assumption of employer discretion based on Work Rules.

Potential Impact of Recent Regulatory Changes

A recent development may influence future disputes. Revisions to the Enforcement Regulations of the Labor Standards Act, effective April 2024, now require employers to provide written clarification at the time of hiring regarding the potential "scope of changes" to job duties and work location that may occur during employment.

- Potential Effects: This requirement could lead to:

- More explicit discussions and documentation of mobility expectations (or limitations) during the hiring process.

- Employers including clearer, broader "change reservation clauses" in contracts to preserve flexibility.

- Potentially fewer disputes based solely on implicit understandings, as parties are prompted to address the issue more explicitly upfront.

- However, the precise interpretation and impact of boilerplate change reservation clauses versus specific hiring circumstances remain areas for future judicial clarification.

Case Study: The Technician Transfer (Supreme Court, April 26, 2024)

The Supreme Court's decision in Social Welfare Corporation Shiga Prefecture Social Welfare Council (Reiwa 5 (Ju) No. 604) provides a definitive statement on the interplay between job scope limitations and transfer orders.

Factual Background

- An employee ("Employee X") possessed specialized technical skills, including welding. He was hired by a social welfare corporation ("Company Y") specifically for a technical role involving the modification and fabrication of welfare equipment at a particular center ("the Specific Work"). He had performed this role exclusively for 18 years.

- The lower courts found that, although not explicitly written down at the time of hiring, an implicit job scope limitation agreement existed between X and Y, limiting his duties to the Specific Work, based on the hiring circumstances and his unique skills and long-term assignment.

- Company Y later decided to discontinue the Specific Work function at the center. Citing the need to avoid redundancy, Company Y ordered Employee X to transfer to a completely different role involving general affairs and facility management, tasks unrelated to his technical expertise.

- Employee X did not consent to the transfer and challenged the validity of the transfer order.

Lower Court Reasoning

Both the District Court and the High Court acknowledged the existence of the implicit job scope limitation agreement. However, they paradoxically concluded that the transfer order was still valid. Their reasoning was based on the principle of dismissal avoidance: since Employee X's original job had disappeared, the transfer to the general affairs role, although outside his agreed scope, was a necessary measure taken by the employer to avoid making him redundant (整理解雇回避, seiri kaiko kaihi). Applying the abuse of right framework from Toa Paint, they found the transfer necessary and not unduly burdensome, thus upholding its validity.

The Supreme Court's Reversal

The Supreme Court decisively rejected the lower courts' reasoning and ruled the transfer order invalid.

- No Authority to Transfer: The Court held that the finding of a valid job scope limitation agreement was paramount. Once such an agreement is established, the employer lacks the fundamental authority (kengen) to order a transfer to duties outside that agreed scope without the employee's consent.

- Abuse of Right Doctrine Not Applicable: The Court clarified that the abuse of right analysis (balancing business necessity vs. employee hardship) is only relevant when the employer possesses the underlying authority to order the transfer. If a scope limitation negates that authority for out-of-scope transfers, the abuse of right doctrine simply does not apply to the question of whether the transfer itself is permissible. The order fails at the prior step due to lack of authority.

- Dismissal Avoidance Cannot Create Authority: The employer's legitimate desire to avoid dismissal cannot magically create the power to transfer an employee in violation of a contractual scope limitation. The Court emphasized that the existence of a limiting agreement restricts the employer's options when the agreed-upon work disappears.

- Correct Legal Path: In such situations, the employer's legally permissible options are typically: (1) seek the employee's genuine consent to a transfer or change in duties (potentially involving negotiation of new terms), (2) find alternative work within the originally agreed scope (if possible), or (3) if neither is feasible, initiate dismissal procedures. The validity of any subsequent dismissal would then be assessed under Japan's stringent dismissal protection rules (Labor Contract Act Art. 16), which require objective, reasonable grounds and social acceptability, including considering whether dismissal could have been avoided through less drastic means (like exploring consensual transfers).

The Supreme Court remanded the case for the lower court to reconsider based on the invalidity of the transfer order.

Analysis and Implications for Employers

This Supreme Court decision provides critical clarity for workforce management in Japan:

- Scope Limitations Trump General Transfer Rights: The ruling leaves no doubt that a specific agreement limiting job scope or work location takes precedence over general clauses in Work Rules that might otherwise permit broad transfer authority. Employers cannot rely on general Work Rules to force employees into roles outside their agreed limitations.

- Distinction Between Transfer Authority and Dismissal Justification: It clearly separates the legal basis for ordering a transfer from the legal requirements for justifying a dismissal. An employer's need to restructure or avoid redundancy might be relevant to justifying a dismissal (if no suitable alternative within the scope exists and consent to change is refused), but it does not grant the right to impose an out-of-scope transfer unilaterally.

- Emphasis on Consent: For employees with scope limitations, moving them to different roles requires their genuine, informed consent. Practices designed to coerce consent or rely on ambiguous assent will face significant legal risk.

- Importance of Contract Clarity: The decision highlights the need for precision in employment agreements. Employers seeking maximum flexibility should ensure contracts explicitly reserve the right to change job duties and work locations broadly. Conversely, if hiring for a truly specialized, limited role, the contract should reflect this clearly to manage expectations on both sides. The recent regulatory change requiring disclosure of the potential scope of future changes further emphasizes this need for upfront clarity.

- Managing Specialized Roles: Particular care is needed when hiring and managing specialists (engineers, researchers, specific professionals). Unless the contract explicitly states otherwise and reserves broad transfer rights, the circumstances of hiring and long-term assignment might lead courts to find implicit scope limitations, restricting future deployment options.

- Responding to Job Elimination: When a specialized role subject to a scope limitation is eliminated, employers must follow a careful process: first, seek genuine consent for a suitable alternative role; second, explore any remaining possibilities within the original scope; only then, if no solution is found, consider dismissal procedures, ensuring compliance with the rigorous standards of Japanese dismissal law.

Conclusion: Defining Roles and Respecting Agreements

The April 2024 Supreme Court decision serves as a powerful reminder that while Japanese employers traditionally enjoyed significant discretion in deploying their regular workforce, this flexibility is fundamentally limited by specific agreements reached with employees. Job scope and work location limitations, whether explicit or implicitly established, are legally binding constraints that negate the employer's authority to order unilateral transfers outside the agreed boundaries.

For businesses operating in Japan, including foreign multinationals, this underscores the critical importance of:

- Precise Employment Contracts: Clearly defining roles, responsibilities, work locations, and, crucially, the scope of potential future changes to these elements. Ambiguity favors the interpretation limiting employer discretion.

- Respecting Agreed Limitations: Recognizing that employees hired for specific roles cannot simply be reassigned to fundamentally different duties without their consent if a scope limitation exists.

- Careful Management of Organizational Change: When restructuring or eliminating roles, meticulously consider any scope limitations applicable to affected employees and prioritize seeking consent for changes before resorting to potentially contentious transfer orders or dismissal procedures.

By ensuring clarity in employment agreements and respecting the boundaries set by job scope limitations, companies can better manage employee expectations, reduce legal risks associated with transfers, and foster more stable and predictable workforce relations in Japan.

- Navigating Japan's "2024 Problem": Work Style Reforms and Their Impact on Business

- Wage Claims for Non-Working Shift Workers in Japan: Understanding Employer Obligations

- Managing Your Japanese Workforce: Navigating Retirement Benefits and Wage Claims

- Model Rules of Employment – English version (MHLW, PDF)