Japan's Supreme Court Upholds Welfare Benefit Cut: The 2012 Old Age Addition Case

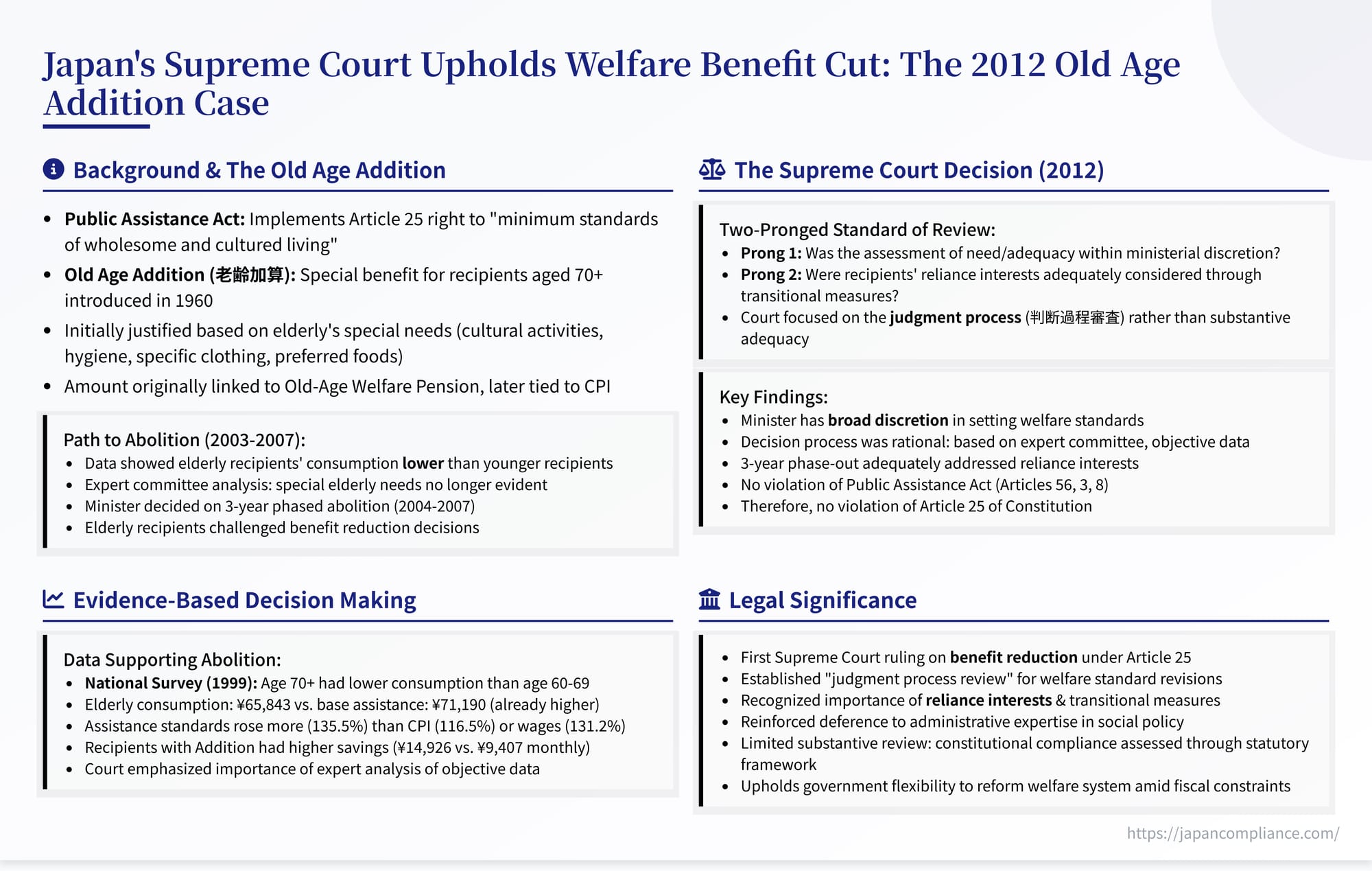

TL;DR: The 2012 Old Age Addition case upheld the phased abolition of an extra welfare payment for seniors, confirming broad ministerial discretion under the Public Assistance Act and Article 25. The Court set a two-prong “process review” test: (1) rationality of need/adequacy assessment and (2) fairness of transitional measures for reliance interests.

Table of Contents

- Background: Public Assistance & Old Age Addition

- Road to Abolition and Legal Challenge

- Supreme Court Reasoning

- Two-Prong Process Review Standard

- Significance for Welfare Policy & Judicial Review

In an era of evolving demographics and fiscal pressures common to many developed nations, the balancing act between maintaining social safety nets and ensuring fiscal sustainability often leads to difficult policy choices and legal challenges. A significant Japanese case shedding light on this tension is the 2012 Supreme Court decision concerning the abolition of the "Old Age Addition" (rōrei kasan) within the Public Assistance system (生活保護法, Seikatsu Hogo Hō). This ruling, formally the Case Concerning Request for Revocation of Decision to Change Public Assistance (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Heisei 22 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 392, Feb. 28, 2012), provides crucial insights into the scope of discretion afforded to government ministries in setting and revising welfare standards, and the standards courts apply when reviewing such decisions, particularly those involving benefit reductions, against the backdrop of constitutional guarantees.

Background: The Public Assistance System and the Old Age Addition

Japan's Public Assistance Act aims to guarantee a minimum standard of living for all citizens in need, pursuant to Article 25 of the Constitution, which enshrines the right to maintain "minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living." The system provides various forms of aid, with Livelihood Assistance (seikatsu fujo) being the core component covering daily living expenses like food, clothing, and utilities.

The amount of Livelihood Assistance is determined based on standards (保護基準, hogo kijun) set by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). These standards are detailed and complex, factoring in household size, age of members, and regional cost-of-living classifications (known as "grades," kyūchi). The standard calculation generally involves summing individual needs (Category 1, dai-ichi-rui) like food and clothing, and household needs (Category 2, dai-ni-rui) like utilities.

In addition to this base amount, the standards historically included various "additions" (kasan) to address specific needs of certain groups. One such addition was the Old Age Addition (rōrei kasan).

- Origin and Purpose: The Old Age Addition was introduced in 1960. Its creation was linked to the start of the Old-Age Welfare Pension the previous year; the addition was initially set at the same amount as the pension benefit and designed to correspond to the non-taxable recognition of that pension income within the public assistance calculation. At its inception, the addition was justified based on perceived special needs of the elderly, with calculations accounting for expenses like cultural activities (theater, magazines), communication, specific clothing items (undergarments, blankets, reading glasses), health and hygiene (fuel for heating, bath fees), and preferred food items (tea, sweets, fruit).

- Evolution: The amount of the addition was initially tied to increases in the Old-Age Welfare Pension. However, from 1976, its calculation method changed, linking it to a percentage (50%) of the average Category 1 base amount for individuals aged 65+ in top-tier regions. Following a 1983 report by the Central Social Welfare Council (an MHLW advisory body), which found that the then-current addition amount generally covered identified special needs of the elderly (related to declining physical/mental functions, social costs, care needs), the addition amount began to be revised based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for relevant Category 1 items starting in Fiscal Year 1984.

The Road to Abolition

By the early 2000s, the Old Age Addition came under scrutiny amidst broader discussions about social security reform and fiscal sustainability.

- Rising Living Standards and Fiscal Concerns: Data indicated that the living standards of public assistance recipients relative to the general working population had significantly improved since the 1970s. The ratio of consumption expenditure of protected households to general worker households, which was around 54.6% in FY1970, had reached roughly 70% by the late 1990s and early 2000s (73.0% in FY2002). The 1983 council report had already deemed the Livelihood Assistance standard generally appropriate relative to general consumption levels. Against this backdrop, fiscal concerns grew.

- External Recommendations: In June 2003, a subcommittee of the Fiscal System Council (an advisory body to the Ministry of Finance) recommended examining the abolition of the Old Age Addition. The recommendation cited fairness concerns relative to recipients under 70, observed trends of decreasing consumption among the very elderly, and the need for consistency with ongoing pension system reforms. That same month, a Cabinet decision ("Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Management and Structural Reform 2003") identified the need to review additions like the Old Age Addition, considering price/wage trends, socio-economic changes, and pension reforms.

- MHLW Expert Committee Review: In July 2003, the MHLW established an expert committee within its Social Security Council to examine the public assistance system. This committee comprised academics (in social security, economics), representatives from social welfare organizations, local government leaders, and others. The committee was presented with various data, including:

- Special Tabulation Data: The MHLW performed a special analysis of data from the 1999 National Survey of Family Income and Expenditure. This analysis compared the "Livelihood Assistance-equivalent consumption expenditure" (total consumption minus items covered by other aid, exempted items, and non-essential expenses like remittances) for single unemployed households across different income and age groups. The data consistently showed that individuals aged 70+ had lower average monthly consumption expenditures than those aged 60-69 (e.g., overall average: ¥107,664 for 70+ vs. ¥118,209 for 60-69; lowest income quintile: ¥65,843 vs. ¥76,761; lowest income decile: ¥62,277 vs. ¥79,817). Furthermore, the average base Livelihood Assistance amount (excluding the addition) for single recipients aged 70+ (¥71,190) was higher than the average relevant consumption expenditure for the lowest income quintile of single unemployed individuals aged 70+ (¥65,843).

- Economic Trends: Data comparing the growth rates of Livelihood Assistance standards, CPI, and wages from FY1984 to FY2002 showed that assistance standards had risen more significantly (135.5%) than CPI (116.5%) or wages (131.2%). Comparing FY1995 to FY2002, assistance standards rose slightly (104.3%) while CPI (99.9%) and wages (98.7%) slightly decreased. Engel coefficients (share of spending on food) had also decreased for both general low-income households and protected households between 1980 and 2000.

- Savings Data: Analysis of a 1999 survey of protected households showed that elderly single households receiving the Old Age Addition had higher average monthly net savings (approx. ¥14,926 vs. ¥9,407), higher average savings rates (12.1% vs. 8.4%), and higher average month-end cash-on-hand (approx. ¥47,071 vs. ¥36,094) compared to similar households not receiving the addition.

- Committee Recommendation (Dec 2003): Based on this evidence, the expert committee issued an interim report concluding that there was no identifiable special consumption need among those aged 70+ corresponding to the amount of the Old Age Addition. It recommended that the addition itself should be reviewed with an eye toward abolition. However, it also stressed the need to consider necessary social expenses for elderly households and ensure that the overall minimum standard of living within the protection standard framework was maintained. It further recommended implementing transitional measures to avoid sudden drops in recipients' living standards.

The Ministerial Decision and Legal Challenge

Following the committee's report, the MHLW Minister determined that the special need justifying the Old Age Addition was no longer evident. The Minister decided to abolish the addition but implement the committee's recommendation for transitional measures by phasing it out over three years.

- Phased Abolition: The protection standards were revised accordingly through MHLW Public Notifications in FY2004 (No. 130), FY2005 (No. 193), and FY2006 (No. 315). These revisions progressively reduced and ultimately eliminated the Old Age Addition between April 2004 and March 2007.

- Benefit Reduction Decisions: Based on these standard revisions, local Welfare Office directors issued individual "protection change decisions" (hogo henkō kettei) to recipients aged 70 and over, reducing their monthly Livelihood Assistance payments commensurate with the reduction and abolition of the Old Age Addition.

- The Lawsuit: Several elderly recipients residing in Tokyo (the Appellants), affected by these reductions, challenged the legality and constitutionality of the underlying standard revisions. They sued the relevant administrative body (represented by the Welfare Office directors), seeking the revocation (torikeshi) of the individual protection change decisions that reduced their benefits. After losing in the District Court and High Court, they appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling

The Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed the appeal, finding the abolition of the Old Age Addition and the consequent reduction decisions to be both lawful under the Public Assistance Act and constitutional under Article 25.

1. Legality under the Public Assistance Act:

The Court first examined whether the revisions violated provisions of the Public Assistance Act itself.

- Article 56 (Protection Against Disadvantageous Changes): The Appellants argued the cuts violated Article 56, which states that protection, once decided, cannot be disadvantageously changed without justifiable reason. The Court rejected this, clarifying the scope of Article 56. It held that this article protects individual recipients regarding their specific, already-determined benefit level. It guarantees their legal status to receive that specific benefit level until a legally defined reason for change, suspension, or termination occurs for that individual and the proper procedures are followed. Article 56 does not, however, govern changes that result from a general revision of the Public Assistance Standards themselves, which apply broadly. Therefore, a reduction in benefits based on a lawful revision of the generally applicable standards does not fall under the purview of Article 56.

- Ministerial Discretion under Articles 3 and 8(2): The Court then addressed the core issue: the Minister's power to revise the standards under Articles 3 (guarantee of minimum standard) and 8(2) (standards must be sufficient for minimum needs). It reaffirmed the principle from the Horiki decision:

- The "minimum standard of wholesome and cultured living" is an abstract and relative concept.

- Giving it concrete form in the protection standards requires highly specialized, technical considerations and policy judgments.

- Therefore, the MHLW Minister possesses discretion based on specialized, technical, and policy perspectives when determining matters such as:

- Whether a special need attributable to old age exists that requires supplementary funding to maintain the minimum standard.

- Whether the overall Livelihood Assistance standard, after a revision (like removing the addition), remains sufficient to maintain a wholesome and cultured standard of living for the elderly.

- Discretion Regarding Reliance Interests and Transitional Measures: The Court introduced an important dimension related to benefit reductions. Even if the Minister reasonably determines that the original justification for an addition (like the special needs of the elderly) no longer exists, abolishing that addition undeniably affects recipients who had planned their lives based on receiving it. This creates a reliance interest or "legitimate expectation" (kitai-teki rieki) tied to the previously concrete standard. The Court ruled that the Minister also possesses discretion, grounded in specialized technical and policy judgment, regarding the method of abolition. This involves balancing the necessity of the abolition (e.g., for fairness with other groups, fiscal reasons) with the need to give due consideration (kakyū-teki ni hairyo) to these reliance interests. This discretion includes deciding whether transitional measures (gekiken kanwa sochi, lit. "measures to mitigate drastic change") are necessary and, if so, what form they should take (e.g., phasing out).

- Standard of Judicial Review for Standard Revisions: Based on this understanding of ministerial discretion, the Court established a specific, two-pronged standard for reviewing the legality of a standard revision that abolishes a component like the Old Age Addition under Articles 3 and 8(2):

- Prong 1 (Need/Adequacy Assessment): Is there an abuse or deviation from the scope of discretion in the Minister's judgment that [a] the special need justifying the addition no longer exists and [b] the revised standard (without the addition) is sufficient to maintain the minimum standard for the affected group (the elderly)? This assessment focuses on potential errors or omissions in the process and procedures used to make the underlying judgment regarding the "concretization of the minimum standard of living."

- Prong 2 (Transitional Measures/Reliance Interests): Is there an abuse or deviation from the scope of discretion in the Minister's judgment regarding the necessity, method, and adequacy of transitional measures? This assessment focuses on whether due consideration was given to the recipients' reliance interests and the impact on their lives, again viewed through the lens of the decision-making process and potential procedural flaws.

The Court clarified that a revision would only be deemed illegal under the Act if it failed one or both of these prongs due to such an abuse or deviation of discretion.

- Application to the Facts: The Court meticulously reviewed the process leading to the abolition:

- The expert committee's role and composition (including academics, practitioners, local leaders).

- The objective data considered (special tabulation of national survey, economic trend data, household savings data).

- The committee's conclusion, based on this data, that the special need wasn't evident and base benefits appeared adequate relative to low-income consumption.

- The committee's recommendation for a phased abolition as a transitional measure.

The Court found that the committee's analysis was reasonably related to objective data and consistent with expert knowledge. The Minister's decision, following this expert process, showed no discernible errors or omissions in the judgment process or procedures regarding the assessment of need and adequacy (Prong 1).

Regarding Prong 2, the Court noted the 3-year phase-out directly followed the committee's recommendation. Considering the data showing significant savings among recipients receiving the addition (suggesting it wasn't always needed for immediate necessities) and the ongoing periodic reviews of the base standards by MHLW (also aimed at preventing sudden drops), the Court found the 3-year phase-out to be a reasonable transitional measure. It concluded that the reduction, implemented this way, could not be assessed as having an "intolerable impact" (kanka shi gatai eikyō) on recipients' lives stemming from the loss of their reliance interest.

- Conclusion on Legality: Therefore, the Court held that the revisions did not involve any abuse or deviation of the Minister's discretion under either prong of its review standard. The revisions were lawful under Articles 3 and 8(2) of the Public Assistance Act. Consequently, the individual benefit reduction decisions (the hogo henkō kettei) based on these lawful standard revisions were also legal.

2. Constitutionality under Article 25:

Having found the standard revisions lawful under the Public Assistance Act, the Court's analysis of the Article 25 claim was remarkably brief.

- It stated that the Public Assistance Act, particularly Articles 3 and 8(2), serves to give concrete form to the guarantee of Article 25.

- Since the revisions were found not to violate these specific statutory provisions that implement the constitutional guarantee, it followed that the revisions did not violate Article 25 itself.

- The Court asserted that this conclusion was evident from the principles established in the Horiki decision.

This approach effectively collapses the constitutional review into the statutory review, suggesting that if the Minister acts within the discretion granted by the statute implementing Article 25, the action is constitutionally sound under Article 25.

3. Other Claims:

The Court summarily dismissed the remaining arguments, stating they amounted to allegations of factual errors or simple statutory violations that did not meet the threshold for review by the Supreme Court.

Significance and Analysis

This 2012 decision is highly significant for several reasons:

- First Supreme Court Ruling on Benefit Cuts: It was the first time Japan's Supreme Court directly addressed the constitutionality and legality of a reduction in the Public Assistance standards, specifically the abolition of an established component like the Old Age Addition. (The Asahi ruling involved a challenge to the adequacy of a standard but was ultimately decided on procedural grounds, with the substantive discussion being obiter dictum).

- Application of "Judgment Process Review": The ruling explicitly applies a standard of review focused on the process by which the Minister reached the decision (判断過程審査, handan katei shinsa). This approach, often used in administrative law to review discretionary administrative dispositions, was applied here to the Minister's quasi-legislative act of revising the protection standards (a form of administrative rule-making). The Court scrutinized the rationality of the process, the evidence considered, and the consistency with expert findings.

- Affirmation of Broad Ministerial Discretion (with Limits): The decision strongly reaffirms the MHLW Minister's broad discretion in setting and revising welfare standards, echoing Horiki. However, it also articulates clear limits based on procedural rationality and the consideration of reliance interests, particularly when reducing or eliminating benefits. The discretion is not absolute but must be exercised based on objective data, expert input, and a reasonable consideration of the impact on recipients.

- Emphasis on Evidence and Expert Input: The Court placed significant weight on the fact that the Minister's decision was based on the recommendations of a diverse expert committee, which in turn relied on detailed statistical analysis. This suggests that administrative decisions involving complex policy judgments are more likely to withstand judicial review if they are grounded in a demonstrably rational, evidence-based process involving expert consultation.

- Introduction of Reliance Interest/Transitional Measures Review: A key development is the Court's explicit inclusion of the need to consider recipients' reliance interests and the adequacy of transitional measures (Prong 2) as part of the judicial review standard for benefit cuts. This acknowledges the real-world impact of such changes and requires the administration to justify not only the cut itself but also the way it is implemented.

- Limited Substantive Review under Article 25?: Perhaps the most debated aspect is the Court's direct linking of Article 25 constitutionality to statutory legality under the Public Assistance Act. By finding the revision lawful under the Act's discretionary framework, the Court concluded it was also constitutional, without undertaking a separate, independent analysis of whether the resulting benefit level substantively met the "minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living" required by Article 25. This approach reinforces the "programmatic rights" view where the legislature and administration define the concrete content of the right, and courts primarily review the process and rationality of that definition, rather than setting the minimum standard themselves. Critics argue this might unduly limit the protective scope of Article 25, potentially allowing substantively inadequate standards to stand if the decision-making process appears formally rational.

Conclusion

The 2012 Supreme Court decision on the abolition of the Old Age Addition is a critical contemporary landmark in Japanese social security law. It upheld a significant reduction in public assistance benefits, emphasizing the broad policy discretion vested in the MHLW Minister to adapt standards based on changing socio-economic conditions and assessments of need. However, it also established that this discretion is not unfettered. Judicial review, while deferential, will examine the rationality of the decision-making process, the evidence considered, the consistency with expert knowledge, and, crucially in cases of benefit cuts, the adequacy of consideration given to recipients' reliance interests and the implementation of transitional measures. The ruling confirms that challenging such policy-driven revisions requires demonstrating a clear abuse or deviation from the Minister's discretion in the judgment process, a high bar for claimants to meet. The case continues to fuel debate on the proper balance between legislative/administrative authority, judicial review, and the substantive guarantee of the right to a minimum standard of living in Japan.

- Asahi Litigation (1967): Supreme Court on Japan’s Constitutional Right to Welfare

- Horiki Litigation (1982): Legislative Discretion and Social Security Benefits

- Gaps in the Safety Net: Student Disability Pensions Case (2007)

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — Public Assistance Standards & Revisions

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000040018.pdf