Japan's Supreme Court on Public Assistance and Savings: The Educational Insurance Case of March 16, 2004

Supreme Court: welfare recipients can save for kids' high‑school fees without aid cuts—landmark 2004 ruling on the Public Assistance Act.

TL;DR

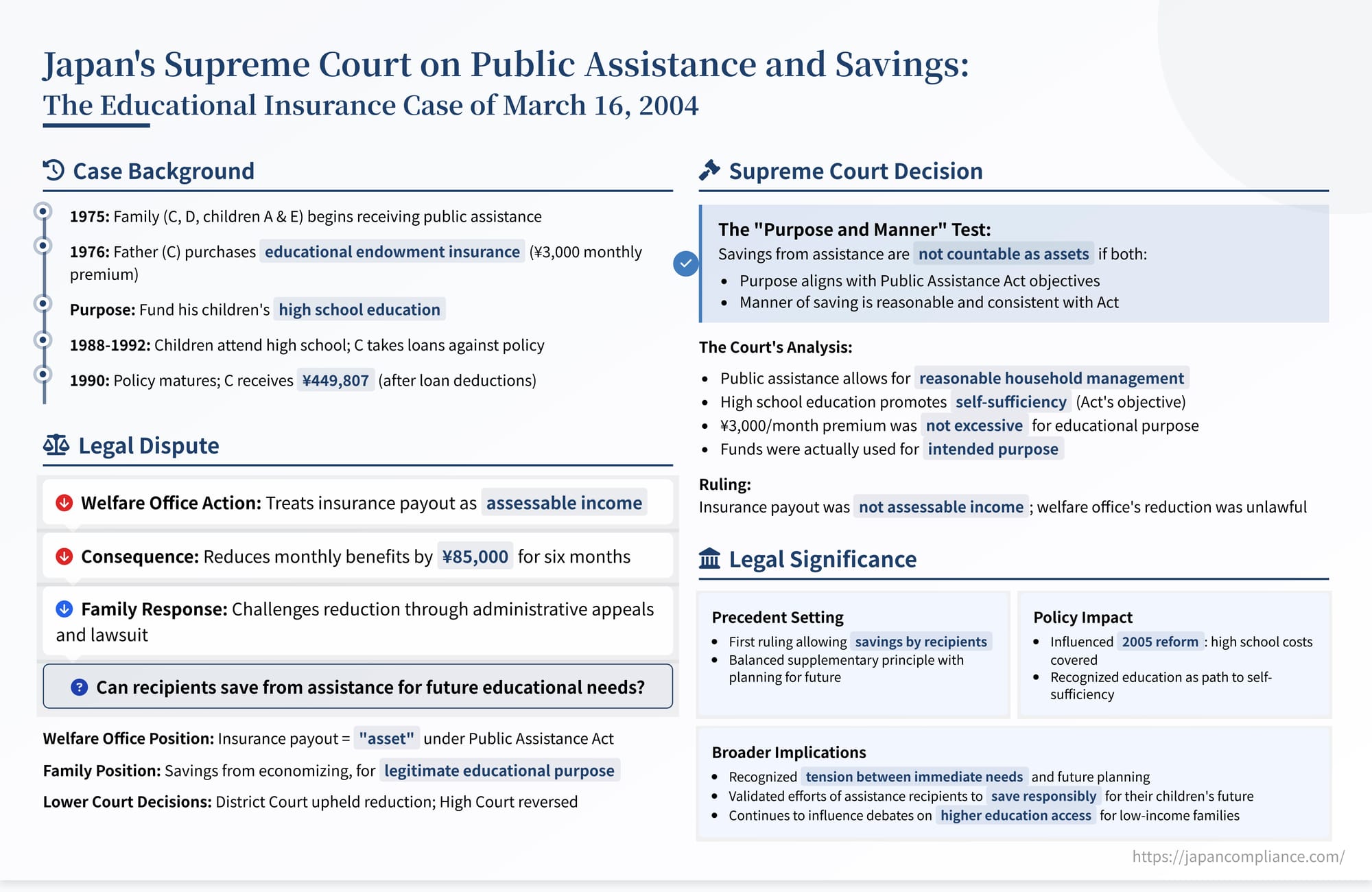

Japan’s Supreme Court ruled in 2004 that savings set aside from public assistance to pay a child’s high‑school costs are not countable assets, provided the purpose and manner of saving align with the Public Assistance Act’s aim of self‑sufficiency. This “purpose‑and‑manner” test shields reasonable, goal‑oriented savings and later prompted policy changes expanding support for high‑school expenses.

Table of Contents

- Background: A Family's Struggle and a Plan for the Future

- The Evolution of Policy on High School Education for Assistance Recipients

- The Dispute: Insurance Payout as Assessable Income?

- The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling

- Significance and Lasting Impact

Japan's Public Assistance Act (the Seikatsu Hogo Hō, hereinafter "the Act") serves as the cornerstone of the nation's social safety net, guaranteeing a minimum standard of living for those in need while promoting their self-sufficiency. A fundamental principle of this system is that individuals must utilize their available assets, abilities, and any other resources to meet their basic needs before receiving public aid. Assistance is intended to supplement the shortfall. This principle raises complex questions when recipients, through diligent economizing, manage to save a portion of their benefits for future needs. Are such savings considered "assets" that must be depleted before further aid is granted? On March 16, 2004, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision addressing this very issue, specifically concerning savings accumulated through an educational endowment insurance policy intended for a child's high school education.

Background: A Family's Struggle and a Plan for the Future

The case involved a family headed by C, who began receiving public assistance in August 1975. C worked as a day laborer, primarily in concrete demolition, but suffered from a hearing impairment and chronic health issues, including diabetes and liver disease, which limited his income and led to repeated hospitalizations. His wife, D, also faced chronic health problems (anemia, nervous gastritis, chronic bronchitis) that hindered her ability to work consistently. The family struggled financially due to C's health, a traffic accident and its after-effects, and economic downturns leading to job loss, ultimately necessitating their application for public assistance.

The welfare authority approved their application, providing livelihood assistance and other necessary aid retroactively from the application date. At that time, the household included C, D, their eldest son E, and their eldest daughter A (one of the eventual plaintiffs/appellees). Their second daughter, B (the other plaintiff/appellee), was born in December 1976. The family subsisted on the public assistance benefits combined with any income C and D earned, which they duly reported according to procedures for income assessment (shūnyū nintei).

In June 1976, about six months before B's birth, C took out an educational endowment insurance policy (gakushi hoken) with the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (the then-operator of the postal savings and insurance system). The policy insured his eldest daughter, A, who was three years old at the time. It was an 18-year maturity policy with a monthly premium of ¥3,000 and a maturity value of ¥500,000. C's stated purpose for purchasing this policy was to cover the future high school education expenses not only for the insured, A, but also for his second daughter, B, who was soon to be born. The premiums for this policy were paid using funds derived from the family's public assistance benefits and any declared income (collectively, kyūfukin tō, or "benefits, etc.").

Educational endowment insurance policies of this type were common savings vehicles designed to help parents prepare for children's educational costs. They typically featured level premiums, a lump-sum payout at maturity (often timed for high school or university entry), and sometimes smaller payouts at earlier milestones (like a "celebration payment" when the child turned 15 under the 18-year plan). They also included life insurance components, paying death or disability benefits if the child passed away or became severely disabled, and often waived future premiums if the parent (policyholder) died.

The Evolution of Policy on High School Education for Assistance Recipients

The context of high school education for children in households receiving public assistance is crucial. Initially, the costs associated with high school were not covered under the Act's educational assistance provisions, which were limited to compulsory education (elementary and junior high school). Administrative practice allowed children to attend high school only through a method called "household separation" (setai bunri). This meant the student was administratively removed from the assisted household, and their living and educational expenses were no longer calculated as part of the household's needs. Families had to find alternative means – often relying on support from relatives or loans – to cover these costs.

Recognizing that high school education significantly contributes to self-sufficiency, administrative practice began to shift in the 1960s. By 1970, a new approach called "in-household schooling" (setai-nai shūgaku) became generally accepted for all high schools (and later, equivalent vocational schools). This allowed children to remain part of the assisted household, receiving support for their basic living expenses under the Act, while attending high school. While direct high school tuition and specific educational costs were still not covered by standard assistance categories at that time, this change acknowledged the importance of secondary education and removed the significant barrier imposed by household separation. By the time C purchased the insurance in 1976, and certainly by the time his children reached high school age (E in 1985, A in 1988, B in 1992), attending high school while receiving public assistance was an established, albeit financially challenging, possibility.

E attended a private high school in Fukuoka City from April 1985, becoming independent and leaving the household upon graduation in April 1990. A attended a private high school in the same city from April 1988, graduating in March 1991. B entered a private high school in Fukuoka City in April 1992 but withdrew in June 1993. C had taken out loans against the educational insurance policy to help finance A's high school expenses, making repayments along the way.

The Dispute: Insurance Payout as Assessable Income?

In June 1990, the educational insurance policy for A matured. After deducting the outstanding amount for the loans C had taken against it, C received a net payout (henreikin) of ¥449,807. During that same month (June 1990), the family received approximately ¥180,000 in total public assistance benefits.

On June 28, 1990, the director of the local welfare office (the appellant Y in the Supreme Court case) issued a decision (the hogo henkō kettei shobun, or "decision to change assistance"). Citing Articles 4(1) and 8(1) of the Act, the office treated ¥445,807 of the insurance payout as assessable income. Consequently, it reduced the family's monthly assistance amount to approximately ¥95,000 per month for the period from July 1990 to December 1990.

The rationale behind this decision rested on the core principle of asset utilization. Article 4(1) mandates that assistance is conditional on the recipient utilizing their assets, abilities, and everything else available for maintaining their minimum standard of living. Article 8(1) requires assistance to be calculated based on the recipient's need, measured against standards set by the Minister of Health and Welfare, after considering their available money and goods. From the welfare office's perspective, the lump-sum insurance payout was "money" or an "asset" that the family now possessed and was required to use for their living expenses before receiving further public funds. Administrative guidance at the time also generally favored the cancellation of insurance policies held by assistance recipients, treating the surrender value or payout as income, although exceptions existed for policies with small values or those deemed essential for self-sufficiency.

C disagreed with this decision and initiated administrative appeals, first to the Governor of Fukuoka Prefecture (dismissed) and then to the Minister of Health and Welfare (also dismissed). Subsequently, C (and later, after his death in 1993, his daughters A and B continuing the suit) filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of the welfare office's decision. They argued the reduction was improper because the insurance policy was specifically purchased and maintained using assistance funds saved through economizing, with the explicit purpose of funding the children's high school education – a goal consistent with the Act's aim of promoting self-sufficiency.

The trial court (Fukuoka District Court) ruled against the family. It acknowledged that if savings from assistance were clearly earmarked and used for a purpose like high school education, treating them as income might constitute an abuse of discretion. However, it found that this particular insurance policy had strong characteristics of general savings and wasn't strictly tied to its intended educational purpose, thus upholding the welfare office's decision as within its discretionary bounds.

The appellate court (Fukuoka High Court) reversed the trial court's decision. It first confirmed that the daughters, A and B, had standing to sue. More significantly, it adopted a different legal framework. It held that savings derived from public assistance funds should not be considered assessable assets under the Act if the purpose and manner (including the amount) of the savings were consistent with the Act's objectives and not considered unreasonable or offensive to general public sentiment. Applying this standard, the High Court found that C's purpose (saving for high school) was legitimate, and the method (a policy with ¥3,000 monthly premiums and a ¥500,000 payout) was reasonable considering the goal and overall circumstances. It ruled the welfare office's income assessment and benefit reduction unlawful. The welfare office appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling

The Supreme Court upheld the High Court's decision in favor of the family, providing crucial clarification on the status of savings made by public assistance recipients.

Reaffirming Core Principles, Acknowledging Practical Realities:

The Court began by reiterating the fundamental principles of the Act: assistance is supplementary, requiring recipients to utilize all available resources (Art. 4(1)), and benefits should meet but not exceed the minimum needs (Art. 8). It acknowledged that, strictly speaking, using assistance funds, which are intended for immediate minimum living needs, for savings is not the primary purpose envisioned by the Act.

However, the Court immediately pivoted to the practical realities of the assistance system. Livelihood assistance, the main component, is generally provided as a monthly cash payment (Art. 31). It's inherently difficult to perfectly match these monthly sums to the fluctuating daily needs of a household. The Act, therefore, implicitly entrusts the head of the household with the responsibility of managing the family budget reasonably. Within this framework of reasonable household management, the Court reasoned, it's possible for recipients, through diligent efforts to economize (as encouraged by Art. 60), to generate small surpluses that could be put aside as savings. The Act does not explicitly require every yen of assistance to be spent within the month it is received.

Furthermore, the Court interpreted Articles 4(1) and 8(1) as not meaning that all assets, regardless of their origin or purpose, must be exhausted before assistance can be granted or continued.

The "Purpose and Manner" Test:

Building on this foundation, the Supreme Court established a key principle: Savings derived from public assistance funds do not constitute assessable assets or income if they were accumulated for a purpose and in a manner consistent with the spirit and objectives of the Public Assistance Act.

The Court identified the Act's core objectives as ensuring a minimum standard of living and promoting self-sufficiency. The critical question, therefore, became whether C's actions in saving through the educational insurance policy met this "purpose and manner" test.

Applying the Test to the Facts:

- Purpose: The Court examined C's objective in purchasing the policy: to fund his children's high school education. While high school costs were not directly covered by educational assistance under the Act, the Court noted the contemporary reality: high school attendance was nearly universal in Japan and widely recognized as beneficial, indeed often essential, for achieving self-sufficiency. Moreover, administrative practice had evolved to support "in-household schooling." Therefore, the Court concluded that striving to save for a child's high school expenses, while maintaining the minimum standard of living provided by assistance, was not contrary to the Act's purpose of promoting self-sufficiency. C's goal was deemed fully aligned with the Act's objectives.

- Manner: The Court considered the specific way C saved: taking out an educational endowment policy with a maturity value of ¥500,000 and paying monthly premiums of ¥3,000 from the household's assistance funds. Without extensive elaboration on why this specific manner was acceptable (unlike the High Court, which considered factors like reasonableness relative to general household savings and public sentiment), the Supreme Court simply concluded that C's actions – purchasing this particular policy for the stated purpose – were "consistent with the spirit and objectives of the Public Assistance Act." This implies an acceptance that the chosen savings vehicle and the amounts involved were not, in themselves, problematic or excessive in the context of saving for a recognized, self-sufficiency-enhancing goal like high school.

- Use of Funds: The Court also briefly addressed the actual use of the payout. Although the funds received by C were the net amount after repaying loans taken against the policy (loans which had been used for educational expenses), the Court found no evidence suggesting the funds were ultimately used in a way that contradicted the Act's purpose. This suggests a degree of flexibility, allowing for the practical application of saved funds, as long as the use remains connected to the original, approved purpose. The Court linked this back to the idea that the Act allows for reasonable household budget management.

Conclusion on Legality:

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that the net payout (the henreikin) received by C from the educational insurance policy, having been saved for a purpose and in a manner consistent with the Act, did not constitute an "asset" under Article 4(1) or "money" under Article 8(1) that should have been assessed as income. Consequently, the welfare office's decision to reduce the family's assistance benefits based on this payout was deemed unlawful due to an erroneous interpretation and application of the Public Assistance Act. The appeal by the welfare office was dismissed.

Significance and Lasting Impact

This 2004 Supreme Court decision was groundbreaking. It was the first time the nation's highest court explicitly ruled that savings accumulated by public assistance recipients from their benefits could, under certain conditions, be shielded from income or asset assessment. It established the crucial "purpose and manner" test, shifting the focus from a rigid view of all savings as immediately available assets to a more nuanced approach that considers the goals behind the savings, particularly goals aligned with achieving self-sufficiency.

The ruling recognized the tension between the principle of utilizing existing assets and the practical need for families, even those receiving assistance, to plan and save for specific, socially accepted future needs like children's education, which ultimately serves the Act's goal of promoting independence.

The practical impact of the decision was significant. It validated the efforts of assistance recipients to save responsibly for their children's future. Partly influenced by this ruling and the societal discussion it reflected, administrative policy changed shortly thereafter. From April 2005, expenses related to high school attendance (such as textbooks, materials, and commuting costs) became eligible for coverage under the Act's Livelihood Assistance category, framed as costs related to skills acquisition (ginō shūtoku hi), a type of support aimed at promoting employment and self-reliance. While direct tuition support often came through separate educational grant programs, this change integrated essential high school costs more formally into the public assistance framework.

Today, while basic high school costs are largely addressed, the debate in Japan continues, now often focusing on the challenges faced by children in public assistance households who aspire to attend university or other forms of higher education – a reflection of the ongoing effort to balance the principles of public support with the aspiration for self-betterment and opportunity through education. This 2004 Supreme Court case remains a vital precedent in that continuing dialogue, affirming that saving for a better future, even under conditions of poverty, can be consistent with the principles of Japan's social safety net.

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- Supreme Court of Japan (English)

- Outline of the Public Assistance System – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare