Japan’s Immigration Overhaul: What the 2023 Amendments Mean for Global Mobility & CSR

TL;DR

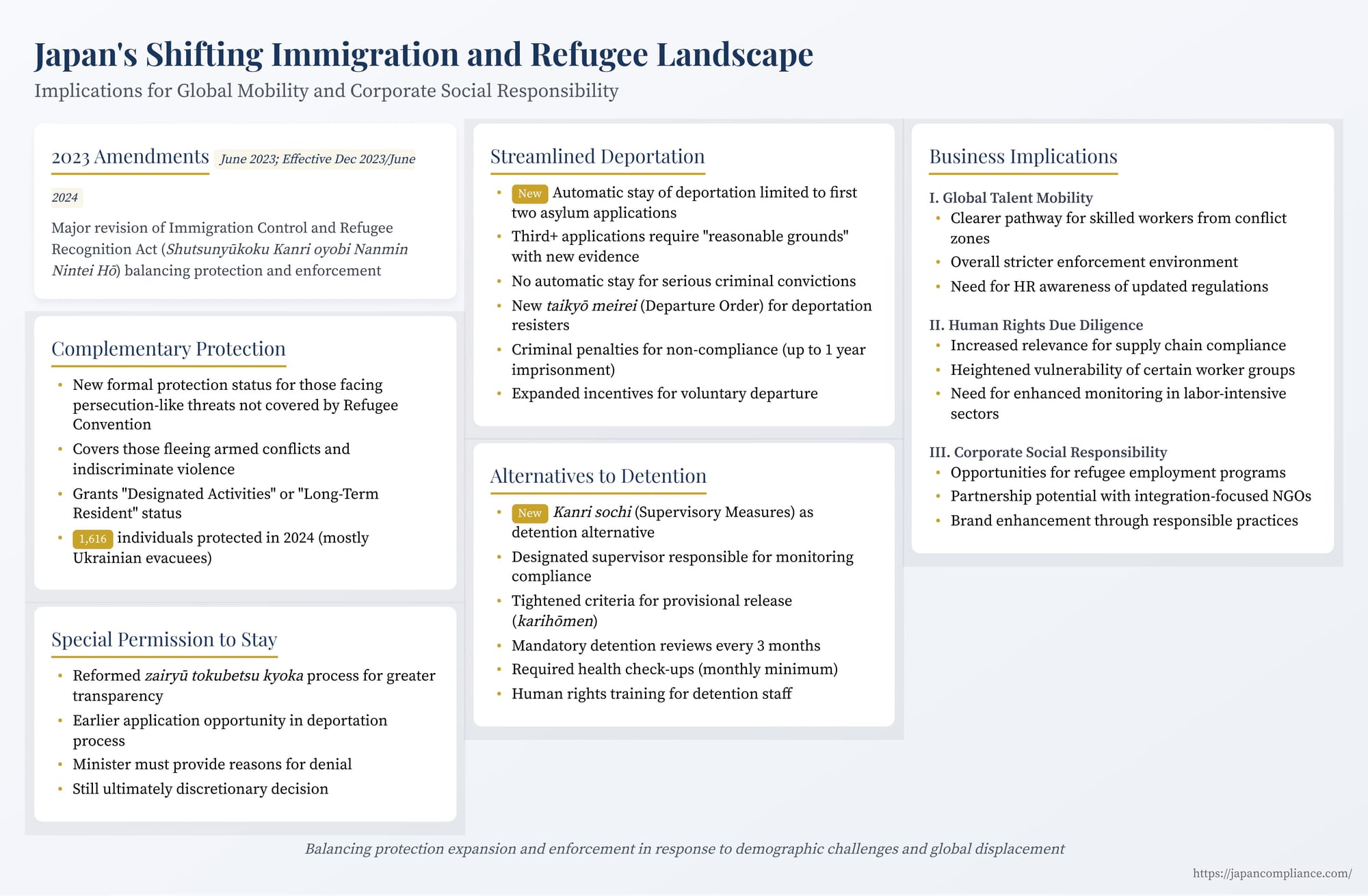

- June 2023 amendments to the Immigration Control Act introduced (i) a Complementary Protection System, (ii) stricter rules for multiple asylum filings, and (iii) alternatives to detention.

- Automatic deportation-stay now applies only to the first two refugee applications; third-time applicants must present new evidence.

- International businesses must monitor talent-mobility impacts, worker-rights risks in supply chains, and CSR opportunities linked to refugee employment.

Table of Contents

- Expanding Protection: The Complementary Protection System

- Reforming Discretion: Special Permission to Stay

- Streamlining Deportation: Limits on Suspension and New Orders

- Alternatives to Detention and Conditions

- Implications for International Businesses

- Conclusion: A System in Transition

Japan, facing significant demographic challenges marked by an aging population and shrinking workforce, is increasingly reliant on foreign nationals to sustain its economy. Concurrently, global displacement due to conflict and persecution continues to drive individuals to seek safety abroad, including in Japan. Against this backdrop, Japan amended its primary immigration law, the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (出入国管理及び難民認定法, Shutsunyūkoku Kanri oyobi Nanmin Nintei Hō, hereafter "Immigration Control Act"), in June 2023, with most key provisions taking effect in December 2023 and June 2024.

These amendments represent a significant overhaul, aiming to balance enhanced protection for those genuinely needing refuge with stricter measures against perceived abuses of the asylum system and facilitating smoother deportation processes. For international businesses operating in Japan, these changes have implications not only for global talent mobility but also for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) considerations and human rights due diligence in supply chains.

Expanding Protection: The Complementary Protection System

Historically, Japan has maintained a very low refugee recognition rate compared to other developed nations, adhering strictly to the definition outlined in the 1951 Refugee Convention. This often left individuals fleeing generalized violence or conflict—who might not meet the Convention's specific persecution criteria—in a precarious legal position, sometimes granted discretionary "special permission to stay" based on humanitarian grounds, but without a clear statutory right to protection.

The 2023 amendments introduced a formal Complementary Protection System (補完的保護対象者認定制度, hokanteki hogo taishōsha nintei seido). This system is designed to protect individuals who do not qualify as Convention refugees but face a well-founded fear of persecution similar to that defined in the Convention, just not based on one of the five Convention grounds (race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion). It also explicitly aims to cover those fleeing indiscriminate violence in situations like armed conflict.

- Scope and Implementation: This system was largely prompted by the need to provide a more stable legal status for evacuees from conflict zones, such as those who arrived from Ukraine following Russia's invasion (though many Ukrainians were initially handled through separate temporary measures). Individuals recognized under complementary protection are typically granted "Designated Activities" or potentially "Long-Term Resident" status, allowing them to reside and work in Japan with greater stability than previously available under purely discretionary humanitarian stay permits.

- Early Statistics: According to Immigration Services Agency data released in early 2025, in 2024 (the first full year of operation), 1,616 individuals were granted complementary protection status, the vast majority being evacuees from Ukraine. While the system provides a formal pathway, the number recognized outside the Ukrainian context remains extremely limited (only 2 individuals in 2023, 45 in 2024 according to preliminary reports). This suggests that while the framework exists, its application to individuals fleeing conflict or danger outside of specific, high-profile situations may still be narrow. Concerns remain about the clarity of criteria and the evidentiary threshold needed to qualify.

Reforming Discretion: Special Permission to Stay

The amendments also aimed to bring more transparency and procedural fairness to the long-standing practice of granting Special Permission to Stay (在留特別許可, zairyū tokubetsu kyoka). This is a discretionary measure granted by the Minister of Justice to individuals found deportable but who have circumstances warranting permission to remain in Japan (e.g., strong family ties, long residence, humanitarian concerns).

Previously, this permission was often considered only at the final stage of deportation proceedings. The revised law establishes a clearer process where individuals can formally apply for this permission earlier. It also requires the government to explicitly state the factors considered when making a decision (such as family situation, conduct, humanitarian needs, domestic and international conditions) and to provide reasons when denying permission. While this aims for greater transparency, the decision ultimately remains within the broad discretion of the Minister of Justice.

Streamlining Deportation: Limits on Suspension and New Orders

Perhaps the most controversial aspects of the 2023 amendments relate to the deportation process, specifically targeting what the government perceived as abuse of the asylum system to delay removal.

- Limits on Automatic Stay of Deportation (送還停止効, sōkan teishi kō): Under the previous system, filing a refugee status application automatically suspended deportation proceedings, regardless of the number of applications filed or their merits. The revised law significantly changes this. Now, the automatic stay of deportation generally applies only to the first two applications. For a third or subsequent application, deportation is not automatically stayed unless the applicant submits prima facie evidence demonstrating a "reasonable grounds" (sōtō no riyū ga aru shiryō) to believe they might qualify for refugee status or complementary protection based on new circumstances arising after their previous applications.

- Exceptions for Criminal Convictions and Security Risks: Deportation is also not automatically stayed for individuals convicted of serious crimes (generally, sentences of imprisonment exceeding one year, though specifics apply) or those deemed a security risk (e.g., suspected terrorists), regardless of whether it is their first or subsequent application.

- Rationale and Concerns: The government argued these changes were necessary to address cases where individuals allegedly filed repeated, unfounded asylum claims solely to prolong their stay and avoid deportation. However, human rights groups, the Japan Federation of Bar Associations, and international bodies like the UNHCR expressed strong concerns. They argue that limiting the stay of deportation raises the risk of refoulement – sending individuals back to countries where they face serious threats, violating international law. Determining the validity of a claim, especially when conditions in the country of origin can change rapidly, requires careful assessment, and critics argue the new system may prevent individuals with genuine protection needs from having their claims fully heard before removal. The effectiveness and fairness of the mechanism for assessing "reasonable grounds" based on new evidence for third-time applicants remain key points of scrutiny.

- New Departure Orders: The revised law introduces a system where immigration authorities can issue a Departure Order (退去等命令, taikyo tō meirei) to certain individuals resisting deportation (e.g., those refusing to board a plane, those whose home country refuses readmission). Failure to comply with this order can result in criminal penalties (imprisonment up to one year or a fine up to JPY 200,000). This aims to address so-called "deportation avoidance" cases (sōkan kihi).

- Facilitating Voluntary Departure: On the other hand, measures were expanded to encourage voluntary departure. Individuals found deportable who cooperate and express intent to leave promptly may be eligible for an "出国命令" (shukkoku meirei, Departure Order under Art. 55-2), which carries a shorter re-entry ban period (1 year) compared to formal deportation (typically 5 or 10 years). This aims to incentivize compliance among those without strong grounds to remain.

Alternatives to Detention and Conditions

Prolonged and indefinite detention of foreign nationals in immigration facilities has been a major source of domestic and international criticism, highlighted by tragic incidents and hunger strikes. The 2023 amendments introduced measures intended to address this, though their practical impact is still being assessed.

- Supervisory Measures (監理措置, kanri sochi): This new system provides an alternative to detention. Individuals subject to deportation who are not deemed a high flight risk can be released under the supervision of a designated "supervisor" (kanrinin), who could be a family member, friend, or support organization staff member. The released individual must adhere to conditions like reporting requirements and residence restrictions. The supervisor is responsible for monitoring the individual's compliance and reporting to immigration authorities; failure to do so can result in administrative penalties. While presented as an alternative, concerns exist regarding the potential burden on supervisors, the stringency of conditions, and whether it will significantly reduce the overall use of detention.

- Revised Provisional Release (仮放免, karihōmen): With the introduction of supervisory measures, the criteria for granting provisional release from detention (a temporary release, often requiring a bond) were tightened. The law now emphasizes health, humanitarian, or other equivalent reasons as the primary grounds, suggesting it may become harder to obtain release solely based on the length of detention if supervisory measures are deemed applicable.

- Detention Review and Conditions: The amendments mandate a review of the necessity of detention every three months. They also explicitly require immigration facilities to provide regular health check-ups (at least monthly) and ensure human rights training for detention staff. These provisions respond directly to criticisms regarding inadequate medical care and alleged mistreatment within detention centers. However, critics argue these measures lack independent oversight and may not be sufficient to prevent future problems without more fundamental reforms to the detention system itself, such as judicial review of detention decisions and legally mandated maximum detention periods, which were not included in the amendments.

Implications for International Businesses

While primarily focused on asylum seekers and individuals in irregular situations, these changes in Japan's immigration and refugee framework have several potential implications for businesses:

- Global Talent Mobility: Although the amendments don't directly target highly skilled foreign workers or intra-company transferees, the overall direction towards stricter enforcement and potentially more complex procedures could subtly influence the environment for foreign nationals. More significantly, companies seeking diverse talent pools might find that individuals potentially eligible for complementary protection (e.g., skilled workers fleeing conflict) now have a clearer, albeit still potentially narrow, pathway to legal status and employment in Japan. Businesses involved in hiring foreign nationals should ensure their HR and legal teams are aware of the updated regulations.

- Human Rights Due Diligence and Supply Chains: The increasing global expectation for companies to conduct human rights due diligence across their value chains (as reflected in Japan's own guidelines) makes the treatment of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees relevant. Companies whose supply chains involve sectors reliant on foreign labor (including potentially vulnerable groups like technical interns or those awaiting status determination) need to be mindful of compliance with labor laws and the human rights standards applicable to these workers. The stricter immigration enforcement environment could potentially increase vulnerabilities for some workers, requiring heightened vigilance from companies committed to responsible sourcing.

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): There is growing interest among some Japanese companies in integrating refugees and protected individuals into their workforce, seeing it as both a talent source and a CSR initiative. Companies like UNIQLO have established programs for refugee employment. The formalization of complementary protection, while limited in scope so far, might create more structured opportunities for businesses looking to engage in such initiatives. Supporting integration programs or partnering with NGOs working with refugees and migrants can align with corporate values and enhance brand reputation.

Conclusion: A System in Transition

The 2023 amendments to Japan's Immigration Control Act represent a complex package attempting to address multiple, often conflicting, pressures: the need for international protection, concerns about system abuse, long-standing issues with detention practices, and the economic reality of requiring foreign labor.

The introduction of complementary protection offers a potential, albeit currently narrow, expansion of protection scope. Efforts to formalize discretionary procedures aim for greater transparency. However, the significant restrictions placed on the stay of deportation for repeat asylum applicants remain highly contentious, drawing criticism for potentially conflicting with international non-refoulement obligations. Similarly, while alternatives to detention and improved conditions are welcome steps, their effectiveness in fundamentally reforming Japan's challenged immigration detention system is yet to be proven.

For international businesses, this evolving landscape necessitates ongoing attention. It impacts not only direct hiring and mobility practices but also resonates within the broader context of human rights, supply chain responsibility, and corporate citizenship. Staying informed about the implementation of these laws, related court challenges, and societal discourse surrounding immigration and refugee issues will be crucial for companies operating responsibly and effectively in Japan.

- Beyond Borders: Germany’s Supply-Chain Act & Mandatory Human-Rights Due Diligence

- Employer Duty of Care in Japan: Protecting Expatriate Staff During Crises

- Navigating Japan’s Legal Landscape During Public-Health Crises

- Immigration Services Agency – 2023 Act Amendments Q&A (Japanese)

- MOFA – Overseas Safety Portal (Japanese)