Japan's Evolving Corporate Governance: The Role and Impact of Outside Directors

TL;DR

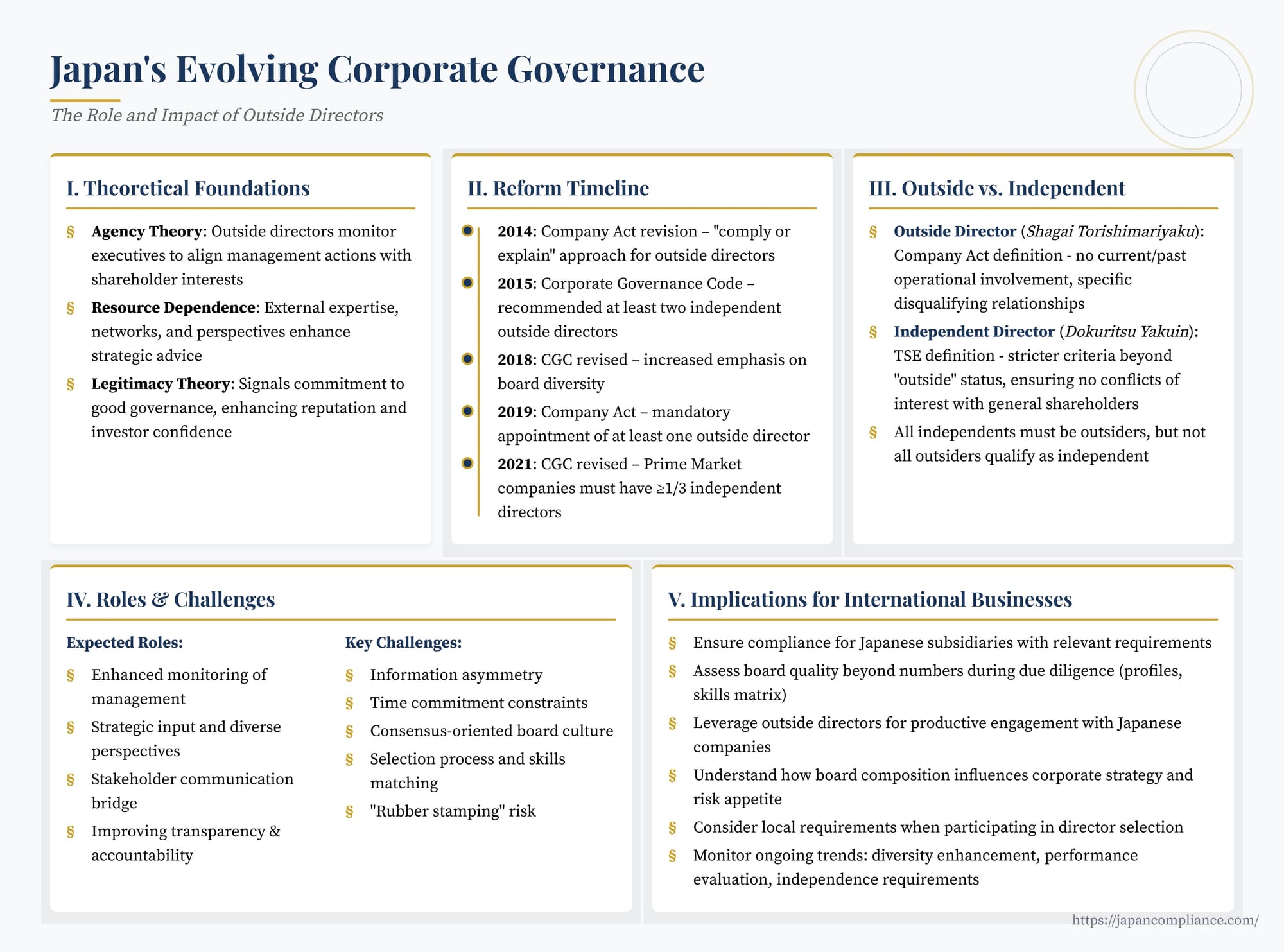

Japan has steadily tightened board-independence requirements—culminating in Prime-Market firms needing ≥1/3 independent outside directors. For global businesses, understanding the legal definitions of “outside” and “independent,” the empirical limits of board-monitoring, and the practical due-diligence points is critical to assessing Japanese subsidiaries and partners.

Table of Contents

- The Theoretical Foundations: Why Outside Directors?

- The Evolution of Outside Directors in Japan: A Timeline of Reform

- Assessing the Impact: Empirical Evidence and Challenges

- Defining “Outside” and “Independent” in Japan

- The Evolving Role and Function in Practice

- Practical Implications for International Businesses

- Future Outlook

- Conclusion

Over the past decade, Japan has embarked on a significant journey of corporate governance reform. Spurred by a desire to enhance corporate competitiveness, attract international investment, and foster sustainable growth, these reforms have placed a strong emphasis on strengthening board oversight and independence. Central to this effort has been the push to increase the presence and influence of outside directors on the boards of Japanese listed companies.

For international businesses engaging with Japan – whether through subsidiaries, joint ventures, investments, or partnerships – understanding this evolving landscape is critical. The composition and functioning of a Japanese company's board, particularly the role and effectiveness of its outside directors, can have tangible impacts on strategy, risk management, compliance, and ultimately, corporate value. This article delves into the transformation of the outside director's role in Japan, examining the regulatory drivers, theoretical underpinnings, empirical evidence on their impact, and the practical implications for businesses navigating the Japanese market.

The Theoretical Foundations: Why Outside Directors?

The global push for outside directors, including in Japan, is rooted in several key corporate governance theories:

- Agency Theory: This is perhaps the most influential driver. Agency theory posits a potential conflict of interest between a company's managers (agents) and its shareholders (principals). Managers might prioritize their own interests (e.g., job security, perquisites) over maximizing shareholder value. Independent outside directors, lacking direct operational ties to the company and management, are seen as crucial monitors who can objectively oversee executive performance, scrutinize major decisions, and align management actions with shareholder interests.

- Resource Dependence Theory: Beyond monitoring, this perspective highlights the valuable resources outside directors can bring. Their external experience, expertise, networks, and diverse perspectives can provide crucial advice, strategic insights, and connections that benefit the company. They can act as advisors, mentors to management, and conduits to external resources or markets.

- Legitimacy Theory (Signaling): Appointing reputable outside directors can enhance a company's legitimacy and reputation in the eyes of investors, regulators, and the public. It signals a commitment to good governance practices, transparency, and accountability, potentially improving stakeholder confidence and access to capital.

While these theories provide a strong rationale, the actual impact of outside directors is complex and context-dependent, as discussed later. Early research, primarily from the US, often focused on the monitoring role, suggesting that boards with a majority of outside directors were more likely to replace underperforming CEOs. However, translating these findings directly to different corporate environments like Japan requires careful consideration of local context and the specific ways reforms have been implemented.

The Evolution of Outside Directors in Japan: A Timeline of Reform

Historically, Japanese boards were often large, dominated by internal executives who had risen through the company ranks, with limited presence of truly independent outsiders. This structure was often seen as facilitating consensus-building and internal coordination but potentially lacking in robust external oversight. Recognizing the need for change, Japan initiated a series of reforms:

- Pre-2010s: While the concept existed, outside directors were relatively uncommon on Japanese boards compared to Western counterparts. The traditional structure often favored internal promotion and knowledge.

- 2014 Company Act Revision: This marked a significant step. It mandated that listed companies lacking any outside directors explain why appointing one would not be appropriate – a "comply or explain" approach. For companies choosing to have a statutory Audit & Supervisory Board (kansa-yaku-kai) structure instead of a US-style committee structure (Nomination, Audit, Compensation committees), it also mandated that at least half of the Audit & Supervisory Board members, and at least one full-time member, be "outside" (shagai kansa-yaku). It also introduced a stricter definition of "outside director" (shagai torishimariyaku).

- 2015 Corporate Governance Code (CGC) Introduced: Following the implementation of the Stewardship Code for institutional investors in 2014, Japan introduced its first Corporate Governance Code. Applying on a "comply or explain" basis to companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), it recommended appointing at least two independent outside directors (Principle 4-8). This spurred a significant increase in appointments across listed companies.

- 2018 CGC Revision: The Code was revised to further strengthen governance, encouraging companies to increase the number of independent directors beyond the minimum of two and enhance board diversity.

- 2019 Company Act Revision: This revision took a further step by making the appointment of at least one outside director mandatory for large, listed companies that did not utilize the committee-based governance structure.

- 2021 CGC Revision & TSE Market Restructuring: A major revision aligned with the TSE's market restructuring (into Prime, Standard, and Growth segments) effective April 2022. Key changes included:

- Prime Market Requirement: Companies listed on the new top-tier Prime Market must appoint independent outside directors constituting at least one-third of the board. If they believe they need more, they should appoint a majority.

- Enhanced Committee Independence: For companies using the committee structure, the revised Code requires a majority of independent outside directors on nomination and compensation committees.

- Diversity & Skills: Increased emphasis on board diversity (gender, international experience, etc.) and ensuring the board possesses a necessary balance of skills (often visualized through a "skills matrix").

This gradual, iterative approach – combining Company Act mandates with the "comply or explain" flexibility of the CGC and reinforced by TSE listing rules – allowed companies time to adapt while steadily raising governance standards, particularly regarding board independence.

Assessing the Impact: Empirical Evidence and Challenges

Does the increased presence of outside directors translate into better corporate performance and governance in Japan? The empirical evidence, much like in other countries, presents a complex picture, and establishing clear causality is challenging.

- The Causality Conundrum: As highlighted in academic research, simply observing a correlation between the number of outside directors and firm value (e.g., stock performance, profitability) doesn't prove that the directors caused the better performance. Several possibilities exist:

- True Causality: Outside directors genuinely improve performance through better monitoring or advice.

- Reverse Causality: Better-performing firms feel more comfortable appointing outside directors (less fear of interference) or can attract higher-caliber candidates. Poorly performing firms might resist appointing outsiders.

- Omitted Variable Bias: An unobserved factor (e.g., a company's proactive international strategy, strong management philosophy) might lead both to appointing more outside directors and achieving better performance, creating a spurious correlation.

- Early Japanese Studies: Research focusing specifically on Japan before the major reforms often mirrored international findings – sometimes finding links between outside directors and specific governance actions (like improved disclosure or reduced earnings management), but often failing to find a consistent, direct positive link to overall financial performance using simple correlation methods. This lack of clear correlation fueled debate during the reform process.

- Theories Explaining Complexity:

- Bargaining Power (Hermalin & Weisbach, 1998): This theory suggests board composition results from negotiation between management and the board, influenced by past performance. Good performance strengthens management's hand (allowing them to appoint insiders), while poor performance weakens it, potentially forcing the appointment of outsiders. This helps explain reverse causality.

- Information Flow (Adams & Ferreira, 2007): This theory emphasizes the dual role of directors: monitoring and advising. Effective advising requires good information flow from management. However, a board perceived as overly focused on monitoring (potentially with too many outsiders) might cause management to withhold information, hindering the advisory function. This suggests that simply increasing the number of outsiders isn't always optimal and the ideal structure depends on the company's specific needs (e.g., firms needing more advice might benefit from fewer, or different types of, outsiders).

- Post-Reform Research & Exogenous Shocks: More recent research attempts to overcome causality issues by using "natural experiments" – situations where regulatory changes force companies to appoint outside directors for reasons unrelated to their prior performance or characteristics. The phased introduction of the CGC and Company Act requirements in Japan provides such opportunities. Studies examining the impact of these mandatory or strongly encouraged appointments tend to find more positive results, suggesting that forcing an increase in board independence, particularly in a context where it was previously low, can have beneficial effects on firm value or specific governance outcomes. This aligns with findings from similar studies in other countries like South Korea, where reforms mandated increased outside director ratios.

- Mixed Picture Remains: Despite progress, the overall empirical picture remains nuanced. The quality, specific skills, and engagement level of outside directors likely matter more than sheer numbers. Furthermore, the impact might vary depending on firm size, industry, ownership structure, and the specific governance outcome being measured (e.g., preventing scandals vs. driving innovation).

Defining "Outside" and "Independent" in Japan

A crucial aspect is understanding how "outside" and "independent" are defined under Japanese rules, as the terms are not always synonymous and differ from US norms.

- Outside Director (社外取締役, Shagai Torishimariyaku): This is a legally defined term in the Company Act (Article 2, Item 15). The definition focuses on a lack of current or recent operational involvement and specific transactional/familial relationships. Key disqualifiers include:

- Being an executive director, manager, or employee of the company or its subsidiaries (currently or within the past 10 years).

- Having held certain non-executive or accounting advisor roles within the past 10 years if they received significant compensation beyond director fees.

- Being an executive of the parent company or a fellow subsidiary.

- Being a major business partner, lender, consultant, or legal/accounting advisor receiving significant payments (beyond a certain threshold) from the company (or having been so recently).

- Being a close relative of an executive or important employee.

- Having received large donations if the director represents a non-profit.

- Independent Director (独立役員, Dokuritsu Yakuin): This term is defined by the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) listing rules and is conceptually aligned with the principles of the Corporate Governance Code. All listed companies must designate at least one independent director from their outside directors. The criteria for independence build upon the "outside" definition but add further requirements aimed at ensuring a lack of conflicts of interest that could compromise objective judgment. These often include:

- Stricter thresholds for past business relationships (e.g., lower transaction values).

- Consideration of cross-directorships.

- Longer "cooling-off" periods for former executives.

- Specific scrutiny of relationships with major shareholders.

- A general requirement that there are no circumstances likely to give rise to a conflict of interest with general shareholders.

While all Independent Directors must first qualify as Outside Directors under the Company Act, not all Outside Directors necessarily meet the stricter independence criteria of the TSE/CGC. Companies must disclose which outside directors they deem independent and explain their reasoning. US businesses should pay attention to this distinction when evaluating the independence level of a Japanese board.

The Evolving Role and Function in Practice

The reforms have undoubtedly increased the number of outside directors on Japanese boards. Their intended role includes:

- Enhanced Monitoring: Overseeing management decisions, performance evaluation, executive compensation, and succession planning. Challenging management proposals when necessary. Ensuring compliance and robust risk management.

- Strategic Input: Providing objective advice, leveraging external expertise and experience to contribute to strategic discussions, and offering diverse perspectives.

- Bridging Stakeholders: Acting as a communication channel between the company, shareholders (especially institutional investors), and other stakeholders. Ensuring management considers broader stakeholder interests.

- Improving Transparency & Accountability: Promoting better disclosure practices and holding management accountable for performance and conduct.

However, challenges remain in ensuring their effectiveness:

- Information Asymmetry: Outside directors often rely heavily on information provided by management, potentially limiting their ability to fully grasp complex issues or identify problems independently.

- Time Commitment: Effectively fulfilling the role requires significant time for preparation, meeting attendance, and engagement outside of formal meetings, which can be challenging for directors with multiple commitments.

- Board Dynamics: Traditional board cultures emphasizing consensus might make it difficult for outsiders to voice dissenting opinions effectively. The effectiveness can depend heavily on the board chair's leadership and the overall board culture.

- Selection Process: Ensuring that appointed outside directors possess the right skills, industry knowledge, independence of mind, and willingness to challenge management is crucial, moving beyond mere compliance with numerical targets. The increasing use of skills matrices is a step in this direction.

- "Rubber Stamping" Risk: There is always a risk that outside directors, due to information gaps, time constraints, or cultural pressures, may simply approve management proposals without sufficient scrutiny.

Practical Implications for International Businesses

The governance reforms in Japan, particularly concerning outside directors, have several practical implications:

- Compliance for Subsidiaries: US companies with listed Japanese subsidiaries must ensure compliance with the relevant Company Act, CGC, and TSE requirements regarding the number and independence of outside directors.

- Due Diligence: When investing in, acquiring, or partnering with Japanese companies, assessing the quality and effectiveness of their board governance, including the independence and caliber of outside directors, is a critical part of due diligence. Look beyond the numbers – examine director profiles, skills matrices, attendance records, and committee compositions.

- Engagement: Institutional investors are increasingly engaging with Japanese companies on governance matters, often focusing on board independence and effectiveness. Understanding the role and perspective of outside directors can facilitate more productive engagement.

- Understanding Decision-Making: Board composition can influence corporate strategy, M&A activity, capital allocation, and risk appetite. Understanding the influence of outside directors helps anticipate a company's direction.

- Recruitment (for Japanese Boards): US companies involved in Japanese entities might participate in nominating or selecting outside directors. Understanding the local requirements, cultural context, and desired skill sets is essential.

Future Outlook

Japan's corporate governance journey is ongoing. While significant progress has been made in increasing board independence through the appointment of outside directors, the focus is shifting towards ensuring their effectiveness. Future trends and potential areas for further development include:

- Continued emphasis on board diversity (gender, nationality, skills).

- Greater scrutiny of director qualifications, time commitments, and performance evaluations.

- Potentially higher independence requirements (e.g., moving towards a majority of independent directors on Prime Market boards, as encouraged by the current CGC).

- Increased focus on the quality of board discussions and decision-making processes.

- Ongoing dialogue between companies, investors, and regulators about best practices.

Conclusion

The role of the outside director in Japanese corporate governance has transformed dramatically over the last decade. From a relative rarity, they have become a mandated and increasingly influential feature of listed company boards, driven by regulatory reforms like the Company Act revisions and the Corporate Governance Code. While theoretical frameworks provide strong justifications for their role in monitoring management and providing resources, empirical evidence on their direct impact on firm value remains complex and context-dependent. Establishing causality is challenging, but studies focusing on reform-driven appointments suggest a positive influence, particularly when independence was previously lacking.

For international businesses interacting with the Japanese market, understanding the definitions of "outside" versus "independent," the evolving regulatory requirements (especially for TSE Prime Market companies), and the practical realities of board functioning is vital. The focus is now shifting from simply increasing numbers to enhancing the effectiveness, skills, diversity, and overall contribution of outside directors to robust oversight and sustainable corporate growth. Japan's commitment to governance reform appears set to continue, making ongoing attention to board composition and dynamics essential for anyone doing business in or with Japan.

- How Can Outside Directors and Auditors Enhance Strategic Decision-Making in Japanese Companies?

- The Evolution of Japanese Corporate Governance: From Shareholder Primacy to Sustainability

- Board Discretion and Director Accountability in Japan: Insights from a 2024 Supreme Court Ruling

- Financial Services Agency – Council of Experts Concerning the Corporate Governance Code