Japan's CFC Rules and Tax Treaties: Supreme Court Upholds Parent Company Taxation

Date of Judgment: October 29, 2009

Case Name: Corporate Tax Reassessment Invalidation Lawsuit (平成20年(行ヒ)第91号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

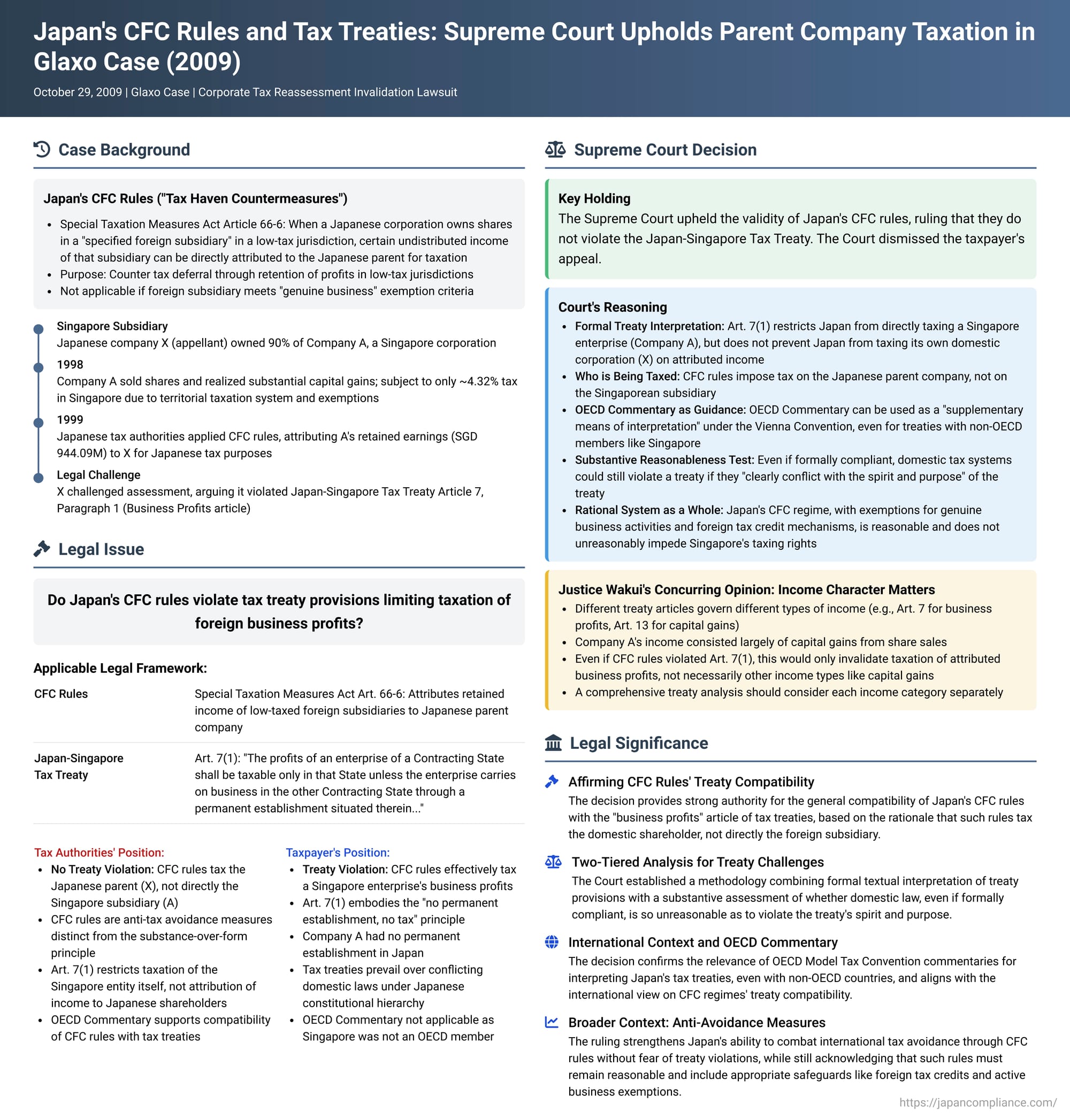

In a landmark decision on October 29, 2009, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the compatibility of Japan's Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) rules—also known as tax haven countermeasure legislation—with the provisions of the Japan-Singapore tax treaty. The Court ultimately affirmed that Japan's CFC rules, which attribute certain undistributed income of a foreign subsidiary in a low-tax jurisdiction to its Japanese parent company for taxation, generally do not violate the "business profits" article of such tax treaties. This ruling hinges on the principle that these rules tax the domestic parent company, not the foreign subsidiary itself.

The Tax Haven Challenge: CFC Rules vs. Treaty Protections

The appellant in this case was X, a Japanese domestic corporation, which held 90% of the issued shares of Company A, a foreign corporation established in Singapore. Company A had initially been engaged in the manufacturing and sales of anti-ulcer medication but transferred this business to a related company in June 1991. In March 1998, Company A sold or cancelled shares it held, realizing substantial capital gains during its fiscal year commencing January 1, 1998. Due to Singapore's territorial tax system and specific exemptions (such as for capital gains on shares), the corporate tax imposed on Company A in Singapore for that fiscal year amounted to only about 4.32% of its relevant income.

The Japanese tax authorities (represented by Y, the tax office head) determined that Company A qualified as a "specified foreign subsidiary, etc." (特定外国子会社等 - tokutei gaikoku kogaisha tō) under Japan's CFC rules. These rules are found in Article 66-6 of the Special Taxation Measures Act (措置法 - Sochihō, the version prior to the 2000 amendment was applicable). Consequently, the tax office attributed Company A's applicable retained earnings (課税対象留保金額 - kazei taishō ryūho kingaku, calculated at approximately SGD 944.09 million for A's 1998 fiscal year) to X as taxable income for X's own fiscal year ending December 31, 1999. A corrective tax assessment and underpayment penalties were issued to X.

X challenged this assessment, arguing primarily that the application of Japan's CFC rules violated Article 7, paragraph 1 of the Japan-Singapore tax treaty ("the J-S Treaty"). X contended that:

- Japan's CFC rules are a manifestation of the "substance-over-form" taxation principle (実質所得者課税の原則 - jisshitsu shotokusha kazei no gensoku), effectively deeming the foreign subsidiary's retained income to belong to the Japanese parent company.

- The retained income of the foreign subsidiary (Company A) should be characterized as business profits.

- Article 7, paragraph 1 of the J-S Treaty embodies the "no permanent establishment (PE), no tax" principle, meaning that the business profits of a Singaporean enterprise (like Company A) can only be taxed in Japan if that enterprise carries on business in Japan through a PE situated therein.

- Company A did not have a PE in Japan.

- Under Japan's constitutional hierarchy, tax treaties generally prevail over conflicting domestic laws. Therefore, taxing X on A's attributed profits under the CFC rules, when A had no PE in Japan, was an impermissible taxation of a Singaporean enterprise's business profits by Japan, contrary to the J-S Treaty.

The tax office (Y) countered that:

- The CFC rules are anti-tax avoidance provisions designed to tax Japanese shareholders on their share of the retained earnings of foreign subsidiaries located in low-tax jurisdictions. This is distinct in purpose and scope from the substance-over-form principle, which typically addresses discrepancies between the nominal and actual recipients of income.

- Crucially, Japan's CFC rules impose tax on the Japanese parent company (X), not directly on the Singaporean subsidiary (Company A). Therefore, Article 7, paragraph 1 of the J-S Treaty, which restricts Japan's right to tax a Singaporean enterprise, is not infringed.

A secondary issue was the applicability of the OECD Model Tax Convention commentary on its Article 7(1) (which generally supports the compatibility of CFC rules with treaty provisions) to the interpretation of the J-S Treaty, given that Singapore was not an OECD member country at the time. The lower courts had ruled in favor of the tax office, and the Supreme Court accepted X's appeal specifically on the question of treaty violation.

The Legal Battle: Who is Being Taxed, and by What Right?

The core of the dispute was whether Japan's CFC rules, by attributing and taxing the undistributed income of a Singaporean subsidiary (Company A, which lacked a PE in Japan) to its Japanese parent company (X), effectively constituted a tax on Company A's business profits in contravention of Article 7, paragraph 1 of the J-S Treaty. This article states that the profits of an enterprise of one Contracting State shall be taxable only in that State unless the enterprise carries on business in the other Contracting State through a PE situated therein; if it does, the profits attributable to that PE may be taxed in that other State.

The Supreme Court's Decision: CFC Rules are Treaty-Compatible

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the compatibility of Japan's CFC rules with Article 7, paragraph 1 of the J-S Treaty.

The Court's reasoning involved several key steps:

- Formal Interpretation of Treaty Article 7(1):

- The Court acknowledged that Article 7(1) of the J-S Treaty confirms the internationally established principle of "no permanent establishment, no tax" for business profits.

- While the article refers to "profits of an enterprise" as the taxable object, its overall structure, particularly the latter part concerning the taxation of profits attributable to a PE, clearly indicates that the article governs the taxation of an enterprise of the other Contracting State. The provision is about which country can tax the Singaporean enterprise, A.

- Therefore, the Court concluded that Article 7(1) is designed to prevent legal double taxation of the Singaporean enterprise's profits. The restriction it places on Japan is limited to Japan's exercise of taxing rights against the Singaporean enterprise (Company A) directly.

- Japan's CFC rules, as stipulated in Article 66-6, paragraph 1 of the Special Taxation Measures Act, deem a certain amount of the foreign subsidiary's retained income as revenue of the domestic Japanese parent company (X), including it in X's taxable income calculation.

- Because this CFC taxation is fundamentally an exercise of Japan's taxing rights over its own domestic corporation (X), it falls outside the scope of the prohibition or restriction imposed by Article 7, paragraph 1 of the J-S Treaty.

- Use of OECD Commentary:

- The Supreme Court stated that since the J-S Treaty is modeled on the OECD Model Tax Convention, the commentary prepared by the OECD's Committee on Fiscal Affairs regarding the Model Treaty can be referred to as a "supplementary means of interpretation" under Article 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, even when interpreting a treaty with a non-OECD member like Singapore.

- The OECD commentary on its Article 7(1) (which corresponds to Article 7(1) of the J-S Treaty) explicitly states that this article pertains to legal double taxation and that CFC-type legislation generally does not violate the Model Treaty. The Court viewed this as an indication that its interpretation aligns with widely accepted international views.

- Substantive Reasonableness Test (Beyond Formal Compliance):

- The Court introduced an important caveat: even if a domestic tax system does not formally or directly violate the letter of a specific treaty provision, its validity could still be questioned if it is so unreasonable that it "clearly conflicts with the spirit and purpose" of the tax treaty. Tax treaties generally aim to appropriately allocate taxing rights between contracting states and to avoid international double taxation.

- The Supreme Court then examined the overall rationality of Japan's CFC tax system:

- Purpose: The CFC rules aim to address situations where Japanese corporations establish subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions (tax havens) and retain income in those subsidiaries to avoid Japanese taxation, thereby ensuring substantial tax fairness.

- Exemptions for Genuine Business Activities: The rules include exemptions (under Article 66-6, paragraph 3 of the Special Taxation Measures Act) for foreign subsidiaries that have genuine economic substance and conduct active business operations in their country of residence (e.g., having offices, shops, factories, or other fixed facilities and engaging in real business activities). Applying the CFC rules to such entities could unduly hinder legitimate overseas business expansion by Japanese companies.

- Foreign Tax Credit Mechanism: When CFC income is attributed to a Japanese parent company, and the foreign subsidiary is also subject to foreign corporate tax on that income, this creates economic double taxation. To mitigate this, Article 66-7, paragraph 1 of the Special Taxation Measures Act provides a foreign tax credit mechanism. This allows the Japanese parent to credit a calculated amount of the foreign corporate tax paid by the subsidiary against its own Japanese corporate tax liability on the attributed income, aiming to achieve a tax burden roughly equivalent to what would have occurred if the subsidiary's profits had been repatriated as dividends.

- Conclusion on Reasonableness: The Supreme Court concluded that Japan's CFC tax system, by pursuing tax fairness while providing exemptions for legitimate business activities and allowing for foreign tax credits to alleviate economic double taxation, constitutes a "rational system as a whole". Therefore, it does not unreasonably impede Singapore's taxing rights or international transactions with Singapore in a manner that would violate the spirit and purpose of the J-S Treaty. The treaty's spirit and purpose do not warrant interpreting it as constraining Japan's sovereign right to enact such CFC rules.

Justice Wakui's Concurring Clarification: Income Character Matters

Justice Norio Wakui, in a supplementary opinion, added an important nuance to the treaty analysis. He pointed out that X's argument focused solely on an alleged violation of Article 7, paragraph 1 (Business Profits) of the J-S Treaty. He suggested that if this argument were successful, it would not automatically invalidate the entire tax assessment on X if the underlying income of the Singaporean subsidiary (Company A) consisted of different types of income.

Justice Wakui elaborated:

- Article 7, paragraph 1 of the J-S Treaty specifically governs the allocation of taxing rights for "business profits" (which roughly corresponds to "事業所得" - jigyō shotoku in Japanese tax terms).

- The J-S Treaty, like most tax treaties, has separate articles that take precedence for different categories of income (as stated in Article 7, paragraph 6 of the J-S Treaty). For example, Article 10 governs dividends, and Article 13 governs capital gains.

- Therefore, a comprehensive treaty compatibility analysis of CFC rules should involve an examination of whether these rules violate the specific treaty article that corresponds to the particular type of income being attributed from the foreign subsidiary to the domestic parent.

- In the case, the facts established by the lower court indicated that a major portion of Company A's undistributed income (which was attributed to X) actually consisted of capital gains from the sale of shares.

- Thus, even if X's argument regarding a violation of Article 7(1) (for business profits) had been successful, it would likely only invalidate the portion of the tax assessment corresponding to attributed business profits. The main part of the assessment, related to attributed capital gains, would need to be analyzed separately under Article 13 (Capital Gains) of the J-S Treaty and would not necessarily be overturned by a finding of an Article 7(1) violation.

Justice Wakui expressed concern that this crucial point about income characterization had not been sufficiently emphasized in previous discussions on the treaty compatibility of CFC rules.

Broader Implications and Significance

The Supreme Court's decision in the case is a cornerstone ruling in Japanese international tax law:

- Affirmation of CFC Rules' Treaty Compatibility: It provides strong authority for the general compatibility of Japan's CFC rules with the "business profits" article (typically Article 7) of its tax treaties. The key rationale is that CFC rules impose tax on the domestic shareholder, not directly on the foreign subsidiary.

- Two-Tiered Analysis for Treaty Challenges: The Court's methodology—first, a formal textual interpretation of the relevant treaty article, followed by a substantive assessment of whether the domestic law, even if formally compliant, is so unreasonable as to violate the treaty's overall spirit and purpose—offers a framework for analyzing future treaty compatibility claims.

- International Context and OECD Commentary: The decision confirms the relevance of OECD Model Tax Convention commentaries as a supplementary tool for interpreting Japan's tax treaties, even those with non-OECD countries, and aligns Japan's stance with the prevailing international view on the treaty compatibility of CFC regimes.

- Nature of CFC Attributed Income: The Supreme Court, in its majority opinion, did not delve deeply into the theoretical characterization of the income attributed under CFC rules (e.g., whether it is a deemed dividend, a direct share of profits, or some other form of income). Instead, it focused on the identity of the taxpayer (the domestic parent company) as the basis for affirming Japan's taxing right. Legal commentary discusses various theories on this point.

- Relevance in Light of Dividend Exemption System: While Japan later introduced a participation exemption system for foreign dividends (exempting 95% of dividends from qualifying foreign subsidiaries from domestic corporate tax), which altered the landscape of tax deferral opportunities that CFC rules were initially designed to combat, CFC rules remain crucial for addressing passive income held in tax havens and certain other international tax planning structures.

- Differing International Judicial Approaches: The decision was rendered against a backdrop of differing judicial outcomes in other countries concerning the treaty compatibility of their respective CFC rules (e.g., a French Conseil d'État decision found a conflict, while a Finnish Supreme Administrative Court decision did not).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's ruling in the case decisively upheld Japan's authority to apply its Controlled Foreign Corporation rules to tax its domestic parent companies on the attributed undistributed income of their low-taxed foreign subsidiaries. The Court found that such taxation does not generally violate standard "business profits" articles in tax treaties like Article 7(1) of the Japan-Singapore treaty, primarily because the tax is levied on the domestic parent, not the foreign entity. Furthermore, the Court deemed Japan's CFC regime, with its exemptions for active businesses and foreign tax credit mechanisms, to be a rational system consistent with the overall spirit and purpose of tax treaties. Justice Wakui's supplementary opinion also added an important layer, emphasizing the need to consider the specific character of the attributed income when analyzing treaty compatibility. This case remains a fundamental precedent in Japanese international tax law, supporting the legitimacy of CFC measures as a tool to combat international tax avoidance.