Japan's Antitrust Reach: Supreme Court Upholds AMA Application to Offshore Cartel Affecting Japanese Market

Date of Judgment: December 12, 2017

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

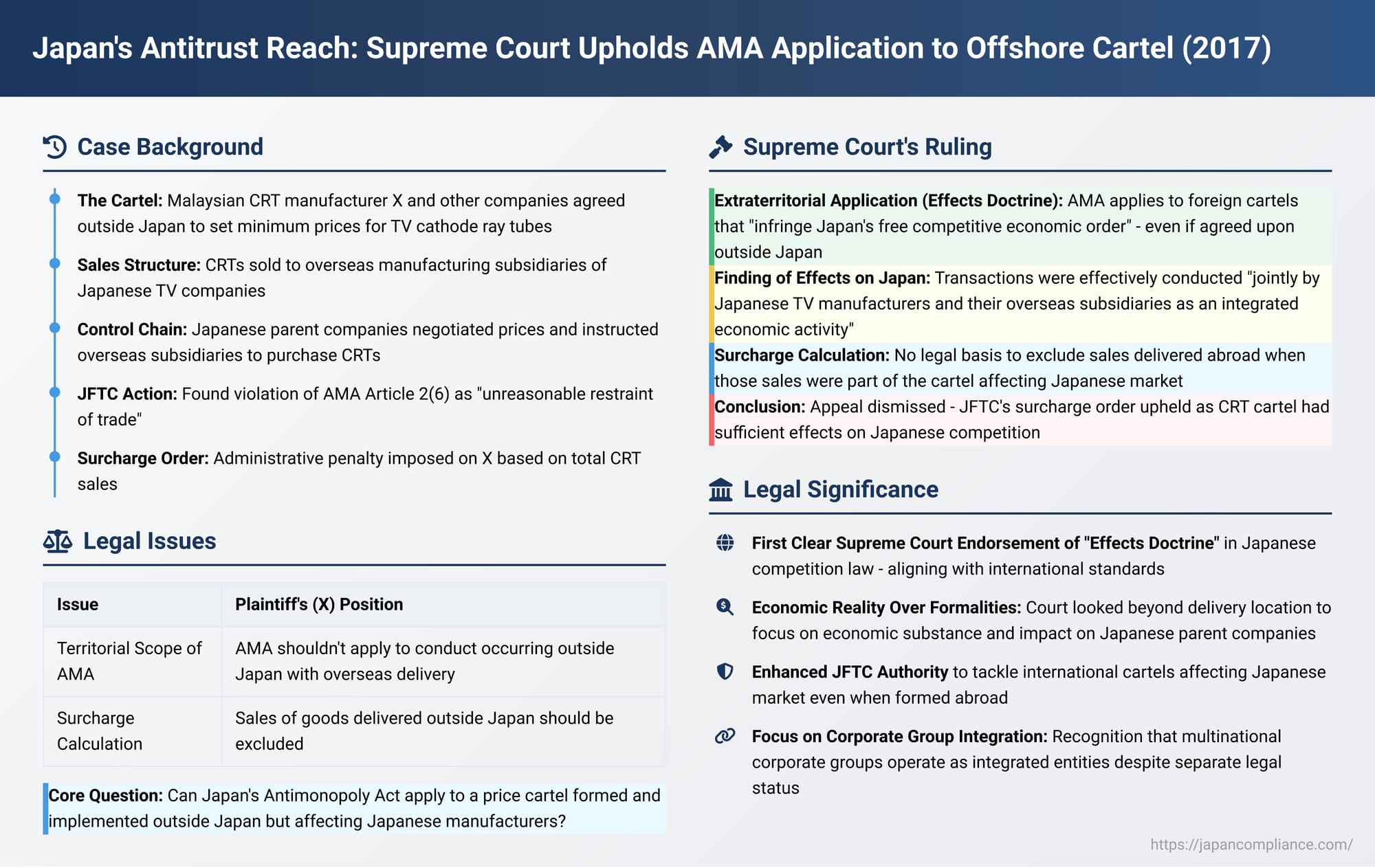

In an increasingly globalized economy, anticompetitive conduct such as international cartels often transcends national borders, posing significant challenges for national competition authorities. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on December 12, 2017, in the "CRT Cartel Case," affirmed the Japan Fair Trade Commission's (JFTC) authority to apply Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA) to a price cartel largely agreed upon and implemented outside Japan, based on the cartel's effects on the Japanese market and its participants. This ruling is seen as a significant endorsement of the "effects doctrine" in Japanese competition law.

The Factual Background: An International Cartel for TV Components

The case involved a complex international cartel for cathode ray tubes (CRTs), a key component in older television sets:

- X (Plaintiff/Appellant): A Malaysian manufacturer of CRTs for televisions, and a subsidiary of A, a major Korean CRT manufacturer.

- The Cartel Agreement: X, along with its parent company A and four other major CRT manufacturers (including their various subsidiaries, totaling around 11 companies), participated in meetings held outside Japan. In these meetings, they agreed to set minimum target prices for CRTs sold to the overseas manufacturing subsidiaries of five major Japanese television manufacturers.

- Japanese TV Manufacturers and Their Overseas Operations: These five prominent Japanese TV manufacturers had established manufacturing subsidiaries or contracted with manufacturing companies in Southeast Asian countries. These overseas entities produced CRT televisions.

- The Purchasing Process and Market Impact:

- The Japanese parent TV manufacturing companies played a central role in the procurement of CRTs. They would negotiate directly with the CRT suppliers (including A and others acting in concert with X) to determine crucial terms such as CRT specifications, overall purchase volume frameworks, and quarterly purchase prices and quantities.

- Following these negotiations, the Japanese TV manufacturers would then instruct their respective overseas manufacturing subsidiaries to purchase the CRTs from the designated suppliers (which included X) based on the terms effectively set with the Japanese parent companies.

- These overseas subsidiaries used the purchased CRTs to manufacture televisions. A substantial portion, if not all, of these finished CRT televisions were then bought back by the Japanese parent TV manufacturers or their affiliated sales companies and subsequently sold in both the Japanese domestic market and internationally.

- JFTC Action: Y (the JFTC, Defendant/Appellee) investigated this arrangement and found that the coordinated actions of X and the other CRT manufacturers constituted an "unreasonable restraint of trade" (不当な取引制限 - futō na torihiki seigen), specifically a price cartel, in violation of Article 2, paragraph 6 of Japan's Antimonopoly Act.

- Surcharge Order: Consequently, the JFTC issued a surcharge payment order (課徴金納付命令 - kachōkin nōfu meirei) against X. This administrative monetary penalty was calculated based on X's sales revenue from CRTs sold to the overseas manufacturing subsidiaries of the Japanese TV companies.

- X's Challenge: X sought a rescission of this order from the JFTC, arguing that the AMA should not apply to its conduct. When this was rejected, X filed a suit with the Tokyo High Court to annul the JFTC's decision. The High Court dismissed X's suit, leading X to appeal to the Supreme Court.

X's primary arguments before the Supreme Court were:

- The Cartel Agreement was made outside Japan, and the CRTs were sold and delivered to overseas manufacturing subsidiaries also located outside Japan. Therefore, X's conduct was beyond the territorial scope of Japan's Antimonopoly Act.

- Even if the AMA applied, the sales revenue used as the basis for calculating the surcharge should be limited to sales of goods where the concrete anticompetitive effects were felt in Japan. Thus, revenue from CRTs delivered outside Japan should have been excluded.

The Supreme Court's Key Rulings

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the JFTC's surcharge order and affirming the extraterritorial application of the AMA in this instance.

1. Extraterritorial Application of the Antimonopoly Act (The "Effects Doctrine"):

The Court addressed the AMA's application to conduct occurring outside Japan:

- AMA's Purpose: The Antimonopoly Act (Article 1) aims to promote fair and free competition, thereby ensuring the interests of general consumers and promoting the democratic and sound development of Japan's national economy.

- Application to Foreign Cartels: In light of this purpose, the Supreme Court held that even if a cartel is agreed upon outside Japan, it is subject to the AMA's provisions (including those for cease and desist orders and surcharge payment orders) if that cartel infringes Japan's free competitive economic order.

- Defining Infringement of Japan's Competitive Order: An "unreasonable restraint of trade" under AMA Article 2(6) means conduct that impairs the competitive function of the relevant market. The Court stated that even if a price cartel is agreed upon abroad, if the cartel restricts competition in which persons located in Japan are counterparties to the transaction, or if Japan is included in the market whose competitive function is thereby impaired, then such a cartel infringes Japan's free competitive economic order. This reasoning is closely aligned with the "effects doctrine" seen in international antitrust enforcement.

- Application to the CRT Cartel:

- The Japanese TV manufacturers, located in Japan, centrally managed and supervised the entire CRT television manufacturing and sales business of their respective corporate groups, including their overseas subsidiaries.

- These Japanese parent companies directly negotiated and decided the crucial terms of CRT procurement (supplier selection, price, quantity) and instructed their overseas subsidiaries to make purchases based on these decisions.

- The Cartel Agreement made by X and other CRT suppliers directly constrained the prices that would be offered to the Japanese TV manufacturers during these negotiations.

- Integrated Economic Activity: The Supreme Court found that, under these facts, the transactions for purchasing CRTs could be evaluated as having been conducted jointly by the Japanese TV manufacturers and their overseas manufacturing subsidiaries as an integrated economic activity.

- Impact on the Japanese Market: Therefore, the Cartel Agreement was deemed to have impaired the competitive function of the market relating to transactions where Japanese TV manufacturers located in Japan were effectively counterparties.

- Conclusion on AMA Applicability: Even though the Cartel Agreement was made outside Japan, it infringed Japan's free competitive economic order. Thus, X's conduct was subject to the surcharge provisions of Japan's Antimonopoly Act.

2. Surcharge Calculation Based on Sales of Goods Delivered Abroad:

The Court also rejected X's argument that the surcharge base should exclude sales of CRTs delivered outside Japan:

- Purpose of Surcharges: The AMA's surcharge system is an administrative measure designed to ensure the effectiveness of the prohibition against cartels by reducing their economic incentives and deterring future violations. It complements other measures like criminal penalties and private damages actions.

- No Limitation in Law or Order: Neither the Antimonopoly Act itself (Article 7-2(1) regarding surcharges) nor its Enforcement Order (which details calculation methods) contains any provision limiting the sales revenue base to goods delivered within Japan.

- Relevance of Impact on Japanese Market: Given that the Cartel Agreement was found to have impaired competition in a market involving Japanese TV manufacturers, the Supreme Court saw no reason to exclude the sales revenue from CRTs delivered abroad (to the overseas subsidiaries participating in the integrated manufacturing process ultimately impacting Japanese consumers and the Japanese economy) from the surcharge calculation base.

- Conclusion on Surcharge Base: The sales amount of the CRTs subject to the Cartel Agreement, even if delivered to overseas manufacturing subsidiaries, properly constituted "the sales amount of said goods" for the purpose of surcharge calculation under AMA Article 7-2(1).

Significance: Affirming the "Effects Doctrine" in Japan

This 2017 Supreme Court decision is of major significance for Japanese competition law:

- Judicial Endorsement of the Effects Doctrine: While the Supreme Court did not explicitly use the term "effects doctrine" (効果理論 - kōka riron), its reasoning is widely interpreted by commentators like Professor Taira as the first clear affirmation by Japan's highest court of this principle for the extraterritorial application of the Antimonopoly Act. This means foreign conduct can be subject to Japanese competition law if it produces requisite anticompetitive effects within Japan or on Japanese markets/entities.

- Alignment with International Norms: This aligns Japan more closely with the approaches taken by other major competition law jurisdictions, such as the United States and the European Union, which have long applied their competition laws extraterritorially based on domestic effects. International customary law is increasingly seen as permitting such application where effects are "direct, substantial, and reasonably foreseeable."

- Focus on Economic Reality over Formalities: The Court looked beyond the formal place of the contracts or delivery (to overseas subsidiaries) and focused on the economic reality: the Japanese parent companies were the true decision-makers and key parties affected by the cartel concerning a critical component for products ultimately impacting Japanese consumers and the national economy.

- Confirmation of JFTC's Enforcement Powers: The ruling confirms the JFTC's authority to investigate and penalize international cartels that harm competition in Japan, even if key collusive activities occur abroad.

Commentary on the Scope of "Effects":

Professor Taira's commentary does raise a question about the depth of the "effects" analysis in this specific judgment. While the SC found an effect on the Japanese competitive order, it did not explicitly quantify the impact on the Japanese domestic market (e.g., the volume of finished TVs sold in Japan incorporating the price-fixed CRTs). He suggests that if the actual domestic effect were minimal, an assertion of jurisdiction and the inclusion of all related foreign sales in the surcharge calculation could potentially be criticized internationally as an overreach of prescriptive jurisdiction.

Conclusion

The "CRT Cartel Case" is a landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court, reinforcing the Japan Fair Trade Commission's ability to tackle international cartels that harm the Japanese economy. By affirming the application of the Antimonopoly Act to conduct agreed upon and partially executed abroad, based on the detrimental effects on competition involving Japanese entities and the Japanese market, the Court has aligned Japan's competition law enforcement with prevailing international standards. The ruling emphasizes a substance-over-form approach, focusing on the economic realities of international business operations and their impact on domestic competition.