Japan's 5-Year Rule for Fixed-Term Contracts: Avoiding Pitfalls for Employers

TL;DR

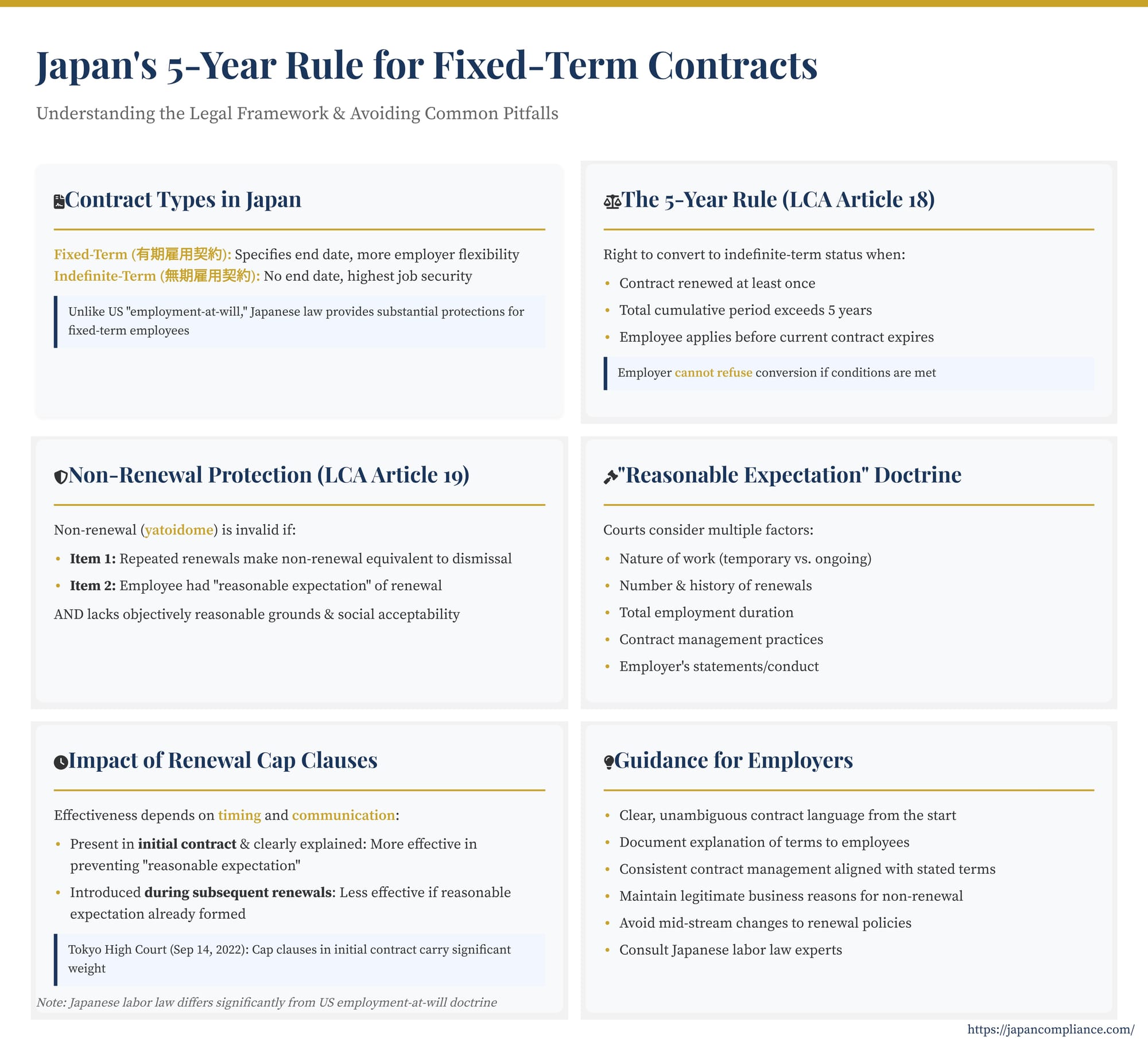

- Under Japan’s Labor Contracts Act, fixed-term employees can convert to indefinite status after 5 consecutive years if they apply before expiry.

- Employers must justify any non-renewal; courts invalidate it where a worker had a “reasonable expectation” of renewal.

- Clear caps written into the very first contract help negate expectations—but later changes often fail.

- Documented business reasons, consistent contract management, and early legal review are key to avoiding disputes and unintended permanent hires.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Fixed-Term Employment in Japan

- Understanding Fixed-Term vs. Indefinite-Term Contracts

- The “5-Year Rule” Conversion Right (LCA Art. 18)

- Non-Renewal & “Reasonable Expectation” (LCA Art. 19)

- Renewal-Cap / Non-Renewal Clauses: Effectiveness

- Practical Guidance for Employers

- Comparison with US Employment-at-Will

- Conclusion: Diligence Is Key

Introduction: The Landscape of Fixed-Term Employment in Japan

Fixed-term employment contracts (yūki koyō keiyaku) are a common feature of the Japanese labor market, utilized by companies across various sectors for flexibility in staffing, project-based work, or probationary periods. However, unlike the default employment-at-will doctrine prevalent in the United States, Japanese labor law provides significant protections for fixed-term employees, particularly concerning contract renewal and conversion to permanent status.

For US companies operating in Japan, understanding these protections, especially the regulations commonly known as the "5-year rule" under the Labor Contracts Act (LCA), is critical. Misinterpreting or mishandling fixed-term contracts can lead to unintended consequences, including employees gaining rights to indefinite-term employment or facing claims of unlawful termination (yatoidome – non-renewal of a fixed-term contract). This article delves into the key provisions of the LCA governing fixed-term contracts—Articles 18 and 19—examining the conversion right, the rules around non-renewal, the crucial concept of "reasonable expectation," and practical strategies for employers to navigate this complex area compliantly.

Understanding Fixed-Term vs. Indefinite-Term Contracts

In Japan, employment contracts are broadly categorized as either indefinite-term (muki koyō keiyaku) or fixed-term (yūki koyō keiyaku). Indefinite-term contracts have no predetermined end date and offer employees the highest level of job security, as termination is strictly regulated under the doctrine of abusive dismissal (LCA Article 16).

Fixed-term contracts, on the other hand, specify an end date. While offering employers more flexibility, their use is not unrestricted. The LCA introduced rules specifically aimed at preventing the indefinite repetition of short-term contracts as a way to circumvent the protections afforded to permanent employees and to promote greater employment stability. The two most significant provisions are Articles 18 and 19.

The "5-Year Rule": The Right to Convert to Indefinite-Term (LCA Article 18)

Article 18 of the LCA establishes what is commonly called the "5-year rule." It grants fixed-term employees the right to convert their employment status to indefinite-term under specific conditions:

- Repeated Renewals: The employee must have had their fixed-term contract renewed at least once.

- Exceeding Five Years: The total cumulative contract period under contracts with the same employer must exceed five years. This calculation includes the duration of the current contract if it pushes the total beyond the five-year mark.

- Employee Application: The conversion is not automatic. The employee must actively apply to the employer for conversion to an indefinite-term contract before their current fixed-term contract expires.

- Employer Acceptance: If these conditions are met and the employee applies, the employer is deemed to have accepted the application. The employment then continues as an indefinite-term contract, generally under the same working conditions (excluding the contract term) as the previous fixed-term contract.

Important Considerations for Article 18:

- Continuity: The five-year period is typically calculated based on continuous employment with the same employer. However, a gap of less than six months between contracts (the "cooling-off period") may not break continuity, depending on the circumstances.

- Not Retroactive: The indefinite-term status begins from the day after the current fixed-term contract (the one during which the application was made) expires.

- Employer Cannot Refuse: If the conditions are met and the employee applies correctly, the employer has no legal grounds to refuse the conversion under Article 18.

The primary purpose of Article 18 is to provide a pathway to stability for long-serving fixed-term employees and deter employers from keeping employees in perpetually precarious fixed-term roles.

Non-Renewal (Yatoidome) and the Doctrine of Abusive Non-Renewal (LCA Article 19)

While Article 18 addresses conversion after five years, Article 19 deals with the validity of an employer's decision not to renew a fixed-term contract when it expires – an act known as yatoidome. This is crucial because an unlawful non-renewal under Article 19 can lead to the contract being deemed renewed, potentially triggering the Article 18 conversion right if the five-year threshold is crossed as a result.

Article 19 essentially extends principles similar to the abusive dismissal doctrine (Article 16) to the non-renewal of fixed-term contracts in specific situations. An employer's refusal to renew a fixed-term contract will be deemed invalid, and the contract considered renewed on the same terms, if either of the following conditions under Article 19 is met and the non-renewal lacks objectively reasonable grounds and is not considered socially acceptable:

- Article 19, Item 1: The contract has been repeatedly renewed in the past, and its non-renewal is equivalent, in socially accepted terms, to the dismissal of an employee under an indefinite-term contract. This applies where the fixed-term contract, despite its label, has become functionally indistinguishable from a permanent position due to numerous renewals and the nature of the work.

- Article 19, Item 2: The employee had reasonable grounds for expecting that the employer would renew the fixed-term contract upon its expiration.

In practice, Item 2 is the more frequently litigated and complex provision.

The Crucial Test: "Reasonable Expectation" of Renewal (Article 19, Item 2)

Whether a non-renewal is valid often hinges on whether the employee held a "reasonable expectation" (gōriteki na kitai) of renewal. This is a fact-specific inquiry where courts consider various objective factors to determine if such an expectation existed at the time of the non-renewal decision. Key factors include:

- Nature of the Work: Was the job temporary, project-based, or did it involve core, ongoing business functions indistinguishable from those performed by permanent employees?

- Number and History of Renewals: How many times has the contract been renewed? A higher number of renewals generally strengthens the expectation.

- Total Duration of Employment: Longer cumulative service periods can contribute to an expectation of continuity.

- Contract Management: Did the employer manage contract expirations strictly, or were renewals treated as a formality? Were procedural steps for renewal consistently followed?

- Employer's Statements and Conduct: Did managers or HR personnel make statements suggesting long-term employment or future renewals? Did company policies or practices imply continued employment? Were performance reviews conducted similarly to those for permanent staff?

- Employee's Perception: While subjective belief alone is insufficient, the employee's understanding based on the employer's conduct is considered.

- Clarity of Contract Terms: Were the terms regarding duration and renewal possibilities (or lack thereof) clear and consistently applied?

If, based on these factors, a court finds that a reasonable expectation of renewal existed, the burden shifts to the employer to demonstrate that the non-renewal had objectively reasonable grounds (e.g., documented poor performance after warnings, significant downturn requiring workforce reduction, completion of a specific project for which the employee was hired) and was socially acceptable (procedurally fair, not discriminatory, etc.). Failing this, the non-renewal is invalid, and the contract is deemed renewed.

The Impact of Renewal Cap / Non-Renewal Clauses

Employers often attempt to manage expectations and limit the application of Articles 18 and 19 by including specific clauses in fixed-term contracts, such as:

- Renewal Caps: Limiting the total number of renewals or the maximum cumulative contract duration (e.g., "This contract may be renewed up to X times," or "The total employment period under this contract and any renewals shall not exceed Y years").

- Explicit Non-Renewal Clauses: Stating clearly that the contract will expire on the end date and will not be renewed.

The legal effectiveness of these clauses, particularly in preventing a "reasonable expectation" under Article 19, Item 2, depends heavily on when and how they are introduced and communicated.

1. Clauses Present from the Initial Contract:

A key takeaway from Japanese case law, including a decision by the Tokyo High Court on September 14, 2022, is that renewal caps or non-renewal clauses present in the initial contract and clearly explained to the employee at the time of hiring carry significant weight in negating a reasonable expectation of renewal. In the Tokyo High Court case, a 5-year maximum duration clause included in the first contract, read aloud and explained to the employee who then signed an acknowledgment, was deemed sufficient to prevent the employee from forming a reasonable expectation of employment beyond five years. The court reasoned that the employee entered the relationship fully aware of the limitation from the outset.

2. Clauses Introduced During Subsequent Renewals:

The situation changes significantly if an employer attempts to introduce a renewal cap or a non-renewal policy after the employee has already worked for some time under previous contracts that did not contain such limitations. If the employee, based on past renewals and other circumstances, has already formed a reasonable expectation of continued employment, simply adding a limiting clause to a renewal contract may not automatically extinguish that expectation.

In such cases, courts often apply principles similar to those established by the Supreme Court in the Yamanashi Kenmin Shinyō Kumiai decision (February 19, 2016) concerning unilateral changes to working conditions. The employer would likely need to demonstrate that the employee genuinely and freely consented to the new, potentially disadvantageous term (the renewal limit), understanding its implications. Merely signing a renewal contract containing the new clause might not be sufficient proof of free consent, especially given the potentially weaker bargaining position of the employee. Factors considered would include the necessity of the change for the employer, the clarity of the explanation provided, the employee's opportunity to understand and object, and whether any mitigating measures were offered.

3. Limitations:

Even with clear clauses present from the start, they are not an absolute guarantee against Article 19 claims. If an employer's subsequent actions or statements contradict the contract terms (e.g., consistently promising long-term roles, treating fixed-term employees identically to permanent staff in all practical aspects over many years), a court might still find that a reasonable expectation was created despite the clause. Consistency between contractual language and actual practice is crucial.

Practical Guidance for Employers in Japan

Navigating Japanese labor law regarding fixed-term contracts requires careful planning and consistent management. Key practical steps for US employers include:

- Clarity in Initial Contracts: Draft fixed-term contracts with unambiguous language regarding:

- The specific contract duration (start and end dates).

- Whether renewal is possible or not.

- If renewal is possible, the criteria and procedure for renewal.

- Any limits on the number of renewals or the maximum cumulative employment period (ensure these are included from the very first contract if intended).

- The specific duties and scope of work.

- Thorough Explanation at Hiring: Ensure that the contract terms, especially duration and renewal provisions (or lack thereof), are clearly explained to the employee before they sign the initial contract. Documenting this explanation (e.g., via a signed checklist) is highly advisable.

- Consistent Contract Management:

- Treat fixed-term employees consistently with the terms of their contracts. Avoid making verbal promises or creating impressions of permanent employment if the contract is truly intended to be temporary.

- Track contract expiry dates diligently. Provide adequate notice of renewal or non-renewal decisions in accordance with the contract and company policy.

- Objective Reasons for Non-Renewal: Even if no reasonable expectation of renewal exists, it is always prudent to have legitimate, documented business reasons for not renewing a contract (e.g., project completion, organizational restructuring, documented performance issues following clear warnings and opportunities for improvement). Avoid reasons that could be perceived as arbitrary or discriminatory.

- Cautious Approach to Mid-Stream Changes: Avoid introducing renewal caps or non-renewal policies for existing fixed-term employees unless absolutely necessary and unless genuine, documented free consent can be obtained. Consult legal counsel before implementing such changes.

- Documentation: Maintain thorough records of all employment contracts, signed acknowledgments of explanations, renewal/non-renewal communications, performance evaluations, and the reasons behind non-renewal decisions.

- Consult Legal Counsel: Given the complexities and potential liabilities, seek advice from experienced labor law counsel in Japan when designing fixed-term contract policies, drafting agreements, or handling non-renewal situations.

Comparison with US Employment-at-Will

It is vital for US employers to recognize that the Japanese legal framework differs significantly from the default employment-at-will doctrine common in most US states. In the US, absent a contract stating otherwise, employers can generally terminate employees for any reason or no reason, as long as it's not an illegal discriminatory reason. There is no general concept of "abusive dismissal" or statutory protection against non-renewal based on "reasonable expectations" in the same way as under Japan's LCA Articles 16 and 19. Attempting to manage fixed-term employees in Japan based on US at-will assumptions can lead to significant legal risks.

Conclusion: Diligence is Key

Fixed-term employment contracts can be a valuable tool for businesses operating in Japan, but they come with specific legal obligations and potential pitfalls under the Labor Contracts Act. The 5-year rule (Article 18) provides a clear path to indefinite-term status for long-serving employees who apply for it, while Article 19 provides crucial protection against arbitrary non-renewal (yatoidome), particularly where a reasonable expectation of continuity has been fostered.

For US employers, successfully managing fixed-term employment in Japan requires meticulous attention to contract drafting from the outset, clear communication with employees, consistent management practices that align with contractual terms, and a thorough understanding of the "reasonable expectation" doctrine. Including well-drafted clauses regarding duration and renewal limits from the initial contract can be an effective risk mitigation tool, as highlighted by recent case law. However, these clauses must be backed by consistent employer conduct. Proactive planning and consultation with legal experts familiar with Japanese labor law are essential to ensure compliance and avoid inadvertently creating permanent employment relationships or facing claims for unlawful non-renewal.

- Workforce Management in Japan: Tackling Indirect Discrimination and the New Freelance Act

- Human Rights in Japanese Supply Chains: Contractual Strategies and Legal Liabilities

- Director Liability in Japan: A Case Study Involving Attorney Directors and M&A

- MHLW | “Points of the Labor Contracts Act – Indefinite-Term Conversion Rule”

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/employ-labour/labour-contracts/indefinite_conversion.html - Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training | Q&A on Fixed-Term Employment (Japanese)

https://www.jil.go.jp/kokunai/statistics/manual/statdata/index.html