Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Murder by Omission: A Deep Dive

Case Number: 2003 (A) No. 1468

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Date of Decision: July 4, 2005

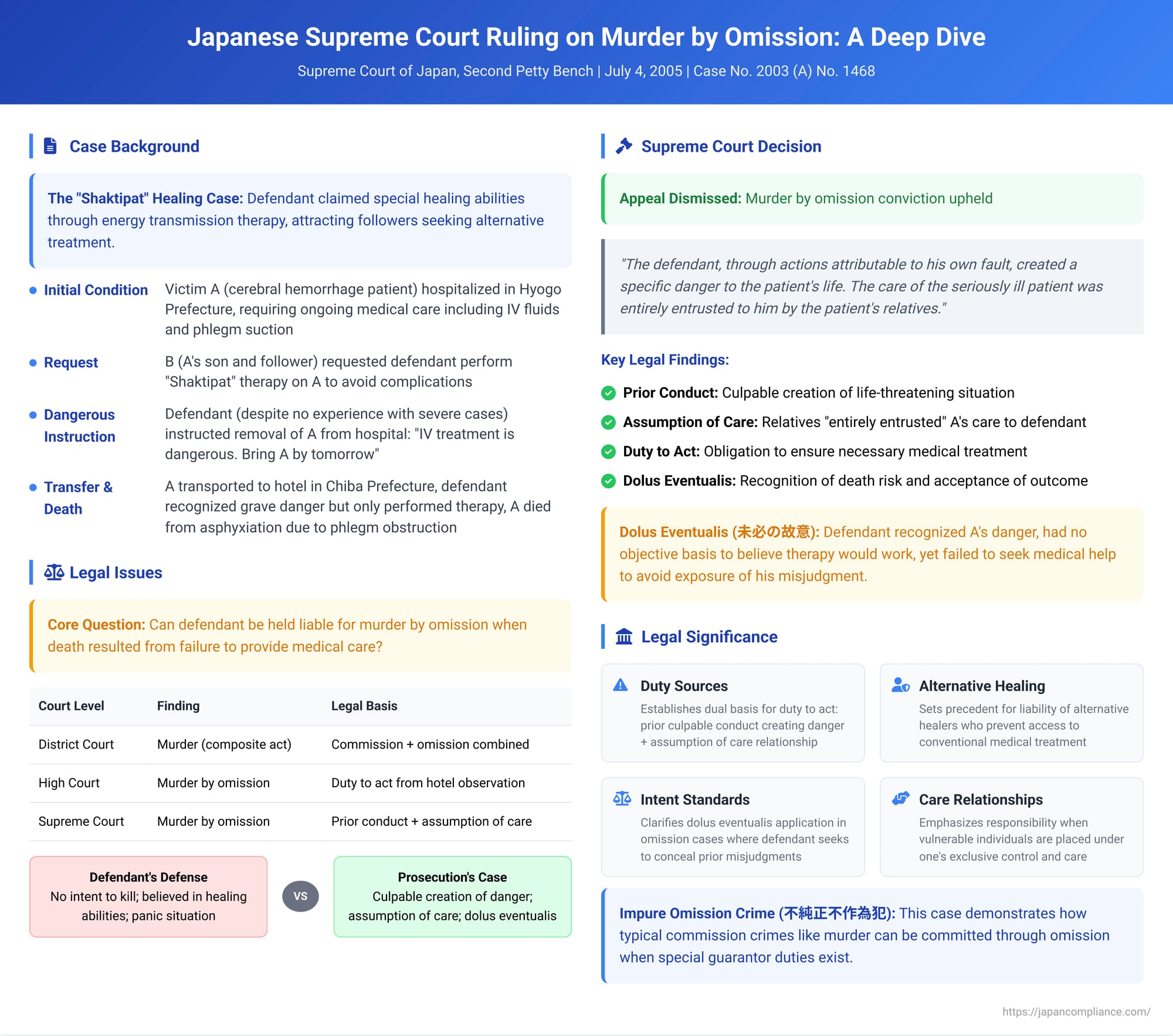

This article delves into a significant decision by the Japanese Supreme Court concerning a charge of murder by omission. The case explores the circumstances under which an individual can be held criminally liable for failing to act, leading to another's death, particularly when a unique, self-proclaimed healing practice is involved.

Case Overview

The defendant in this case was known for promoting and practicing a unique therapy, which he referred to as "Shaktipat" (hereinafter "the therapy"). He claimed this practice, involving tapping on a patient's affected areas to transmit "energy" and enhance their self-healing capabilities, endowed him with special abilities, thereby attracting a group of followers.

The victim, A, was a follower of the defendant. A suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and was hospitalized in Hyogo Prefecture. While A's life was not in immediate danger, A was in a state of impaired consciousness, requiring ongoing medical care such as phlegm suction and intravenous fluids. Recovery was expected to take several weeks, with a likelihood of lasting side effects.

B, A’s son and also a follower of the defendant, hoped for A’s recovery without any residual complications. B approached the defendant and requested that he perform the therapy on A.

The defendant had no prior experience performing his therapy on patients with serious conditions like cerebral hemorrhage. Despite this, he accepted B's request. He instructed B to bring A to a hotel in Chiba Prefecture where he was staying, to undergo the therapy. This instruction was given even though the defendant was aware that A's attending physician had warned that discharging A from the hospital was not feasible for some time. He was also aware that B and A's family initially intended to seek the physician's permission before moving A. The defendant, however, told B and others, "Intravenous drip treatment is dangerous. Today and tomorrow are critical. Bring A by tomorrow." Consequently, B and others removed A, who was still in need of medical treatment including IV fluids, from the hospital, thereby creating a concrete danger to A's life.

A was subsequently transported to the aforementioned hotel. The defendant was entrusted by B and other relatives with A's care for the purpose of administering the therapy. Upon observing A's condition at the hotel, the defendant recognized that A was in danger of dying if left as is. However, primarily to avoid the exposure of his misjudgment in instructing A's removal from the hospital, the defendant only administered his therapy. With dolus eventualis (constructive intent or recklessness plus), he left A for approximately one day without arranging for necessary medical measures to sustain A's life, such as phlegm removal or hydration. As a result, A died from asphyxiation due to airway obstruction by phlegm.

Procedural History

The first instance court, the Chiba District Court (decision dated February 5, 2002), found the defendant guilty of murder. It ruled that the defendant's actions, specifically instructing B and others to remove A from the hospital and bring A to a hotel lacking medical facilities, combined with his subsequent failure to take any necessary life-sustaining measures at the hotel, constituted a "composite act of commission and omission" fulfilling the elements of murder.

The defendant appealed. The Tokyo High Court (decision dated June 26, 2003) upheld the murder conviction but on a different basis. It determined that murderous intent (dolus eventualis) could only be recognized from the point the defendant personally observed A's condition at the hotel. The High Court reasoned that the defendant's prior act of instructing B and others to remove A from the hospital and bring A to the hotel created a duty for him to immediately provide or arrange for the necessary medical treatment to sustain A's life. His failure to do so constituted murder by "impure omission" (where a crime typically committed by an act is committed by an omission).

The defendant appealed to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court dismissed the defendant's appeal, upholding the High Court's conviction for murder by omission. The Court, after reviewing the facts, exercised its authority to rule on the applicability of murder by omission.

The Supreme Court affirmed the lower court's findings of fact:

- The Defendant's Practice: The defendant had garnered followers by claiming special abilities in his unique therapy.

- The Victim's Condition and Family's Hopes: A, a follower, was hospitalized after a cerebral hemorrhage, requiring ongoing medical care. A's son, B, also a follower, sought the defendant's therapy for A, hoping to avoid long-term complications.

- Defendant's Instructions and Creation of Danger: Despite lacking experience with such severe cases and knowing the treating physician's warnings against A's discharge, the defendant instructed B to bring A to his hotel. This act of having A removed from the hospital, where A was receiving necessary medical care, and brought to a non-medical facility, created a concrete danger to A's life. The Court emphasized that this creation of danger was due to "reasons attributable to the defendant's own fault."

- Defendant's Recognition of Danger and Subsequent Omission: At the hotel, the defendant was entrusted with A's care by A's relatives. He observed A's grave condition and recognized the risk of death. However, to conceal his earlier misjudgment, he merely performed his therapy. Crucially, he failed to provide or arrange for essential life-sustaining medical treatment, acting with dolus eventualis. A subsequently died from asphyxiation.

Based on these facts, the Supreme Court reasoned as follows:

The defendant, through actions "attributable to his own fault," created a specific danger to the patient's (A's) life. Furthermore, at the hotel where A was brought, the defendant was in a position where the care of the seriously ill patient was "entirely entrusted" to him by the patient's relatives, who were his followers.

At that point, the defendant recognized the patient's critical condition. He had no objective basis to believe he could save A's life through his own therapy. Therefore, the Court concluded that the defendant bore an obligation (duty to act) to immediately ensure that the patient received the necessary medical treatment to sustain life.

Despite this duty, the defendant, acting with dolus eventualis (i.e., recognizing the possibility of A's death and accepting that outcome), failed to provide such medical treatment and instead left the patient unattended, leading to A's death.

The Supreme Court held that these circumstances established murder by omission on the part of the defendant. It also noted that, regarding A's relatives who lacked murderous intent, the defendant could be considered a joint principal with them for the crime of "abandonment by a protector resulting in death," but only to the extent of the elements of that lesser offense.

The Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment, which reached the same conclusion on the defendant's guilt for murder by omission, to be legitimate.

Legal Analysis and Key Takeaways

This case is pivotal in understanding how Japanese criminal law addresses murder by omission, particularly the establishment of a "duty to act."

1. Murder by Omission (不作為による殺人 - Fusakui ni Yoru Satsujin)

Murder, as defined in Article 199 of the Japanese Penal Code, is typically an offense committed through an affirmative act (a "crime of commission"). However, Japanese jurisprudence recognizes that murder can also be committed by an omission—a failure to perform an expected act, specifically, the failure to actively rescue a life in peril. This is known as an "impure crime of omission" (fushinsei fusakuihan).

For liability for murder by omission to arise, the omission must be deemed equivalent to causing the result (death) through an affirmative act. This equivalency is established by demonstrating a "special obligation to act" or a "guarantor status" (hoshōjinteki chii or sakui gimu). The core legal question in such cases often revolves around when such a duty to act exists.

2. The Basis for the Duty to Act (作為義務 - Sakui Gimu)

The Supreme Court in this decision identified two key factual circumstances that formed the basis of the defendant's duty to act:

- Prior Conduct Creating Danger (先行行為 - Senkō Kōi): The defendant's actions in instructing A's removal from a hospital, despite knowing A's critical need for ongoing medical care and the treating physician's advice, directly led to a "concrete danger to the patient's life." The Court explicitly stated this danger was created "due to reasons attributable to the defendant's own fault." This element of culpable prior conduct that creates or significantly exacerbates a risk to life is a well-recognized source of a duty to act in Japanese criminal law theory. When an individual's actions place another in peril, a legal duty to take reasonable steps to mitigate that peril can arise.

- Assumption of Care and Reliance (保護の引受け・依存関係 - Hogo no Hikiuke / Izon Kankei): Once A was brought to the hotel, A's relatives, who were the defendant's followers, "entirely entrusted the care of the seriously ill patient" to him. This created a situation of dependence and reliance. The defendant, by accepting B's request and having A brought to a location under his control for the purpose of his therapy, assumed a position of responsibility for A's well-being. This assumption of care, especially when the victim is vulnerable and reliant on the caregiver, is another significant factor in establishing a duty to act. The defendant was not a mere bystander; he had actively involved himself in A's situation and had become the focal point for A's care in that specific context, to the exclusion of professional medical intervention he himself had engineered.

The Supreme Court found that the combination of these two elements—the defendant's culpable creation of a life-threatening situation and his subsequent acceptance of the role of primary caregiver in that situation—solidly established his legal duty to take necessary medical measures to save A's life.

3. Dolus Eventualis (未必の故意 - Mihitsu no Kōi)

A critical element for a murder conviction is the presence of intent (koi). In this case, the Court affirmed the finding of dolus eventualis. This form of intent, often translated as "conditional intent" or "recklessness plus," means that the defendant did not necessarily desire the victim's death as the primary goal. However, the defendant recognized that their actions (or, in this case, omissions) carried a significant risk of causing death and accepted that possibility, proceeding with their course of conduct regardless.

The defendant, upon seeing A's deteriorating condition at the hotel, "recognized that A was in danger of dying if left as is." Despite this awareness, and having "no objective basis to believe he could save A's life through his own therapy," he chose not to seek professional medical help. The Court inferred that this choice was motivated by a desire to "avoid the exposure of his misjudgment in instructing A's removal from the hospital." This conscious disregard of a known, high risk to A's life, coupled with the acceptance of the potential fatal outcome, satisfied the criteria for dolus eventualis.

4. Causation (因果関係 - Inga Kankei)

For an omission to lead to criminal liability, a causal link between the failure to act and the harmful result must be established. In this case, A died from asphyxiation due to airway obstruction by phlegm. The necessary medical measures not taken included phlegm removal and hydration. The Court found that had the defendant fulfilled his duty to act—by, for instance, immediately arranging for A to be transported to a hospital or summoning emergency medical services—A's death by asphyxiation could have been prevented. The failure to provide these life-sustaining measures was thus a direct cause of A's death.

5. Scope of Joint Criminal Responsibility (共同正犯 - Kyōdō Seihan)

An interesting ancillary point in the Supreme Court's decision is its comment on joint principals. It stated that the defendant was guilty of murder by omission. Regarding A's relatives (like B), who were involved in moving A but lacked murderous intent, the Court suggested the defendant could be considered a joint principal with them for the crime of "abandonment by a protector resulting in death" (hogo sekininsha iki chishi), but only to the extent of the elements of that less severe offense. This touches upon a complex area of Japanese criminal law concerning "heterogeneous complicity" (ishitsu no kyōhan), where participants in a crime may have different levels of criminal intent regarding the outcome. The primary finding, however, remained the defendant's sole culpability for murder due to his own actions, his specific duties, and his dolus eventualis.

Broader Implications

This Supreme Court decision reinforces established principles regarding murder by omission in Japanese law but also provides a clear application of these principles to a unique factual scenario involving alternative healing practices. It underscores that:

- Individuals who, through their culpable actions, create a life-threatening situation for another person may incur a legal duty to act to prevent harm.

- Voluntarily assuming the care of a vulnerable individual, particularly when this leads to the exclusion of other forms of assistance, can also give rise to a duty to provide necessary aid.

- The law will scrutinize the conduct of those who offer unconventional treatments, especially when they dissuade or prevent individuals from seeking or continuing necessary conventional medical care, leading to grave consequences.

- A claim of special healing abilities does not absolve an individual of the duty to procure necessary medical care when a person under their effective control is in manifest danger, especially if the "healer" recognized the danger and had no reasonable basis to believe their methods alone would be effective.

- The desire to protect one's reputation or conceal prior misjudgments is not a valid defense for failing to act when a life is at stake and a duty to act exists.

This ruling serves as a stark reminder of the legal responsibilities that can arise from one's actions and subsequent omissions, particularly when individuals place themselves in positions of trust and control over vulnerable persons. The Court's focus on the defendant's creation of risk and assumption of care provides a clear framework for analyzing similar cases of omission liability.