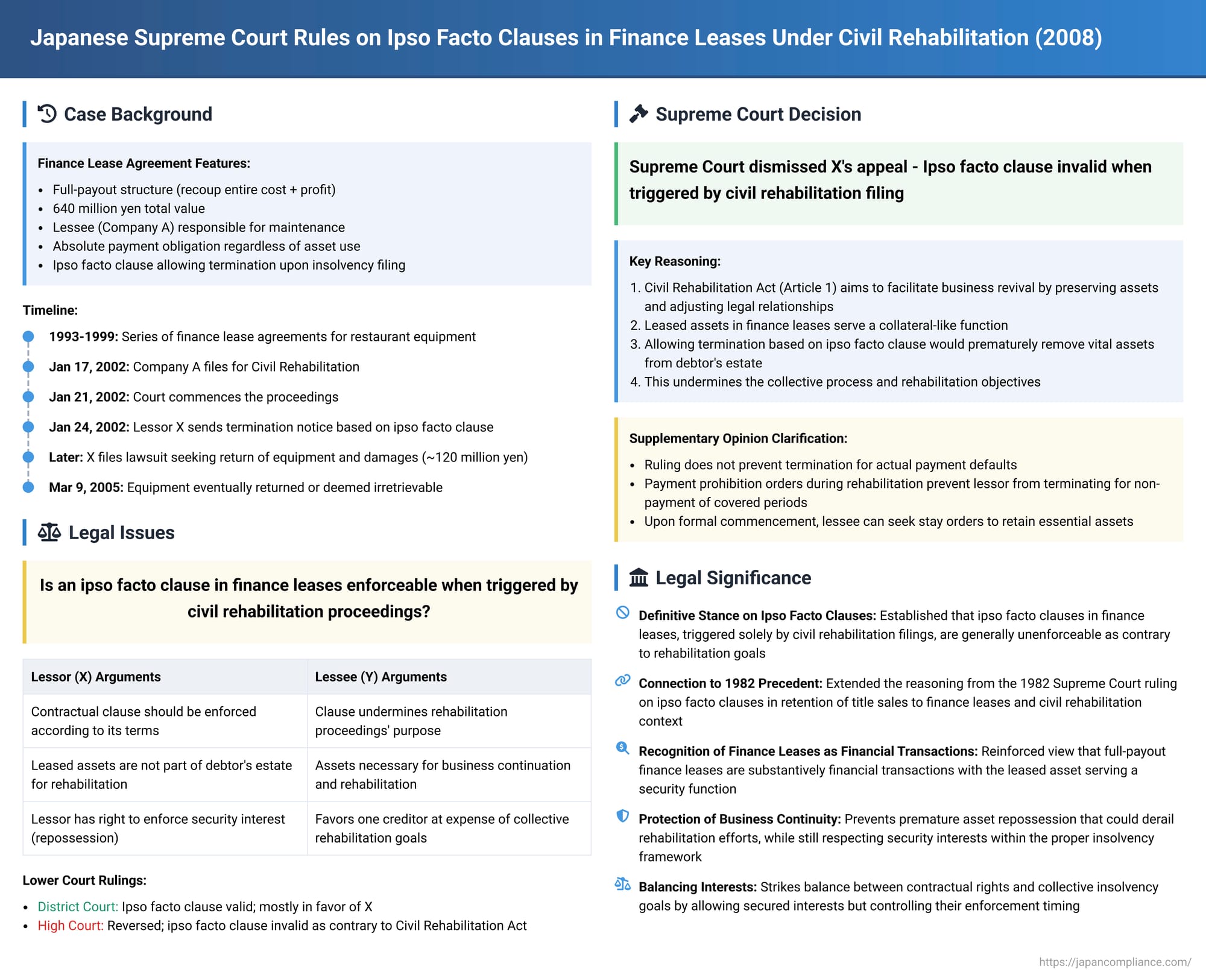

Japanese Supreme Court Rules on Ipso Facto Clauses in Finance Leases Under Civil Rehabilitation

Date of Judgment: December 16, 2008

Case Name: Claim for Delivery of Movables, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

This blog post delves into a significant judgment by the Supreme Court of Japan concerning the enforceability of ipso facto clauses within full-payout finance lease agreements when a lessee files for Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings. An ipso facto clause is a contractual provision that triggers a default or termination of the agreement automatically upon the occurrence of certain events, such as a party's insolvency or filing for bankruptcy protection.

Case Background: The Lease and Insolvency

The case involved a lessor, company X (the Appellant), and a lessee, company Y (the Appellee). Company Y had succeeded to the contractual lease obligations of company A, a restaurant chain operator, following a merger. Company X was the successor to the original lessor, company B.

Between May 1993 and March 1999, a series of lease agreements were concluded. Initially, company B leased kitchen equipment and other items ("Property 1") to company A. Subsequently, after company B itself entered corporate reorganization proceedings, its trustee entered into further lease agreements with A for additional items ("Property 2"). Later, company X, having acquired B's leasing business, also entered into lease agreements with A for the remaining parts of Property 1. Collectively, these items constituted "the Leased Properties."

The total value of these lease agreements, structured as full-payout finance leases, was approximately 640 million yen. A full-payout finance lease is designed so that the lessor recovers the entire cost of the leased asset, plus interest and other expenses, through the stream of lease payments over the lease term.

Key terms of these lease agreements included:

- The lessor would purchase an asset specified by the user (lessee) and lease it to the user.

- The user was responsible for all maintenance, repair, and upkeep of the leased asset.

- If the user missed even a single lease payment, the lessor could terminate the contract without notice. Upon termination, the user was obligated to return the leased asset and pay all outstanding lease fees plus an amount approximating the sum of all future scheduled lease payments as stipulated damages.

- The user's obligation to pay lease fees was absolute and not excused by non-use or inability to use the leased asset for any reason during the lease term.

- The user could not make any claims against the lessor regarding any defects in the leased asset after its delivery.

- If the leased asset was lost or irreparably damaged due to natural disaster or other causes, the contract would terminate, and the user would be liable for stipulated damages.

- Crucially, the agreements contained a special clause (an ipso facto clause) stating that if the user became the subject of a petition for "arrangement, composition, bankruptcy, corporate reorganization, etc.," the lessor could terminate the contract without notice. It was understood that the filing for Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings fell within the scope of this clause.

On January 17, 2002, company A filed a petition for the commencement of Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings with the Tokyo District Court. The court issued an order commencing these proceedings on January 21, 2002.

Three days later, on January 24, 2002, company X (the lessor) sent a notice to A, invoking the ipso facto clause and declaring the lease agreements terminated due to A's filing for civil rehabilitation. X subsequently filed a claim in the rehabilitation proceedings for stipulated damages (though this claim was later withdrawn during an appeal). X also initiated the present lawsuit, seeking the return of the Leased Properties and damages equivalent to the lease fees from the day after the purported termination until the properties were returned or deemed irretrievable (amounting to approximately 120 million yen, claimed as administrative expenses/priority claims).

The Leased Properties were eventually returned to X or became irretrievable by March 9, 2005. Company Y, which had merged with A, assumed A's position in the lease agreements and the ongoing litigation.

Lower Court Rulings

The court of first instance largely sided with X, upholding the validity of the termination based on the ipso facto clause and granting most of X's claims.

However, the High Court (the appellate court) reversed this decision. It held that the ipso facto clause, insofar as it allowed termination solely due to the filing of a petition for commencement of Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings, was contrary to the spirit and purpose of the Civil Rehabilitation Act and therefore invalid. Consequently, the termination based on this clause was deemed ineffective. The High Court only recognized X's claim to a minor extent, limited to approximately 900,000 yen that was already in arrears at the time of the purported termination. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the High Court's decision.

The Court reasoned as follows:

The Leased Properties were subject to full-payout finance lease agreements. The ipso facto clause in these agreements permitted termination if, among other things, a petition for the commencement of Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings was filed against the lessee. The Supreme Court found that, at least the portion of this clause that designated the filing for civil rehabilitation as a ground for termination, must be considered null and void as it contravenes the spirit and objectives of the Civil Rehabilitation Act.

The Court elaborated on its reasoning:

- Purpose of Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings: The Civil Rehabilitation Act (Article 1) aims to rehabilitate a debtor facing financial difficulties by preserving their assets as a whole, adjusting legal relationships between the debtor and all creditors based on a rehabilitation plan approved by a majority of creditors, and thereby facilitating the revival of the debtor's business or economic life. Importantly, property that is subject to a security interest is also included within the debtor's estate, which is the target of the rehabilitation proceedings.

- Nature of Leased Assets in Finance Leases: In a finance lease, the leased asset serves a collateral-like function. If lease payments are not made, the lessor can terminate the lease, demand the return of the asset, and use its repossession and subsequent disposal (its exchange value) to satisfy claims for unpaid lease payments or stipulated damages.

- Conflict with Rehabilitation Objectives: To allow termination based on an ipso facto clause triggered by a civil rehabilitation filing would mean that an asset, which essentially serves as collateral, could be removed from the debtor's estate before the commencement of the rehabilitation proceedings, merely due to a prior agreement between one creditor (the lessor) and the debtor. This would deprive the debtor of the opportunity, within the rehabilitation process, to address the necessity of the leased asset for its business operations and overall rehabilitation. Such an outcome, the Court concluded, clearly undermines the spirit and objectives of the Civil Rehabilitation Act.

Therefore, the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's judgment that the ipso facto clause (allowing termination due to the civil rehabilitation filing) was invalid, and consequently, X's termination of the lease agreements on this basis was ineffective.

Significance and Implications of the Decision

This Supreme Court judgment carries significant weight in Japanese insolvency law, particularly concerning finance lease agreements.

- Invalidity of Ipso Facto Clauses in Civil Rehabilitation: The ruling definitively establishes that ipso facto clauses in full-payout finance lease agreements, which are triggered by the lessee's filing for Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings, are generally unenforceable because they conflict with the fundamental goals of this rehabilitative insolvency regime. This aligns with a broader principle in Japanese insolvency law that aims to protect the debtor's estate and provide a fair process for all creditors.

- Reinforcement of Earlier Precedents: The decision builds upon an earlier Supreme Court precedent (a 1982 case) which had invalidated a similar clause in a sales contract with retention of title where the buyer faced corporate reorganization proceedings. The current judgment explicitly extends this reasoning to finance leases and, significantly, to Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings, which, unlike corporate reorganization, traditionally offers less interference with secured creditors' rights (treating them as having a "right of separate satisfaction").

- Nature of Finance Leases as Financial Transactions: The Supreme Court's reasoning implicitly supports its consistent view that full-payout finance leases are, in substance, financial transactions. They are seen as a means for the lessee to acquire the economic benefits of an asset with financing provided by the lessor, rather than a simple operating lease or rental. The Court's focus on the "collateral significance" of the leased asset underscores this perspective. The lease payments are not merely for the use of the asset but represent the repayment of the financed acquisition cost and associated charges.

- Protection of the Debtor's Estate: A core theme is the protection of the debtor's estate ("responsibility財産" - sekinin zaisan). Allowing a lessor to unilaterally retrieve a potentially essential business asset merely because of an insolvency filing would prematurely deplete the estate and hinder the court's and creditors' ability to formulate a viable rehabilitation plan that might involve the continued use of such assets.

- Distinction from Termination for Actual Default: It's crucial to note that this judgment addresses the invalidity of ipso facto clauses (termination triggered solely by the insolvency filing itself). It does not generally prevent a lessor from terminating a lease agreement if the lessee commits an actual breach of contract, such as failing to make lease payments, subject to other applicable rules and procedures within the insolvency context (discussed further below in relation to the supplementary opinion).

Insights from a Justice's Supplementary Opinion

A supplementary opinion by one of the justices provided further clarification on the nature of finance leases and the interplay between termination clauses and insolvency proceedings, particularly concerning orders prohibiting payment.

- Defining Finance Leases: The opinion highlighted that, from an accounting perspective (referencing Japanese accounting standards which evolved from Ministry of Finance ordinances), a "finance lease" inherently implies a non-cancellable lease where the lessee substantially enjoys the economic benefits and bears the costs associated with the leased asset (a full-payout structure). Accounting standards generally require such leases to be treated akin to a sale and purchase on the lessee's balance sheet (asset capitalized, lease obligation recorded as debt), though alternative treatments with footnote disclosures were historically permitted until reforms mandated the capitalization method for fiscal years starting on or after April 1, 2008. Understanding this economic and accounting substance is vital when considering the legal nature of such transactions.

- Termination for Non-Payment vs. Ipso Facto Termination: The opinion reiterated that the main ruling (invalidating the ipso facto termination) does not affect the lessor's right to terminate a lease due to the lessee's failure to pay lease fees (a default in performance). If the lessee is in arrears, the lessor can, in principle, terminate based on this breach. Furthermore, lease agreements often contain acceleration clauses, stipulating that upon an insolvency filing, all future lease payments become immediately due. The validity of such acceleration clauses, in general, is not negated by this ruling.

- Effect of Payment Prohibition Orders: A critical point raised was the interaction with "弁済禁止の保全処分" (bensai kinshi no hozen shobun), which is a provisional order prohibiting the debtor from making payments, often sought by the debtor concurrently with filing for Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings.

- If such an order is granted, the debtor is legally barred from paying lease fees that fall due after the order.

- As a reflexive effect, the lessor is then generally prohibited from terminating the lease agreement based on the non-payment of those specific lease fees covered by the payment prohibition order. This is because the non-payment is a direct consequence of a court order, not a simple default by the lessee. (This references a 1982 Supreme Court precedent.)

- Post-Commencement of Proceedings: However, the landscape changes once Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings are formally commenced by a court decision ("開始決定" - kaishi kettei).

- The initial payment prohibition order (the hozen shobun) typically ceases to be effective upon the commencement decision.

- At this point, while the Civil Rehabilitation Act itself generally prohibits payments on pre-petition rehabilitation claims (Article 85, Paragraph 1), the lessee might technically fall into a state of default regarding ongoing lease obligations if not handled appropriately.

- The lessor, potentially viewed as a creditor with a right of separate satisfaction (a "別除権者" - betsujo-kensha, similar to a secured creditor), might then attempt to exercise its remedies, including contract termination and repossession of the leased asset.

- To counter this, if the leased asset is necessary for the continuation of the debtor's business and its rehabilitation, the debtor can petition the court for a stay order ("中止命令" - chūshi meirei) against the enforcement of the lessor's rights (Article 31, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Rehabilitation Act). This mechanism allows the debtor to retain use of the asset while the rehabilitation plan is being developed.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 16, 2008, decision significantly clarifies the treatment of ipso facto clauses in finance lease agreements under Japan's Civil Rehabilitation Proceedings. By invalidating such clauses when triggered by a rehabilitation filing, the Court prioritized the objectives of business revival and the comprehensive adjustment of creditor rights inherent in the civil rehabilitation framework. This approach recognizes the economic reality of finance leases as financing mechanisms and seeks to prevent the premature dismantling of a debtor's operational capacity, thereby providing a better opportunity for successful rehabilitation. It underscores a careful balancing act between contractual rights and the broader aims of insolvency law to foster economic recovery.