Japanese Supreme Court on "Voluntary" Developer Fees: When Administrative Guidance Becomes Illegal Coercion

Case Title: Claim for Refund of Educational Facility Burden Fee

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Judgment Date: February 18, 1993

Case Number: 1988 (O) No. 890

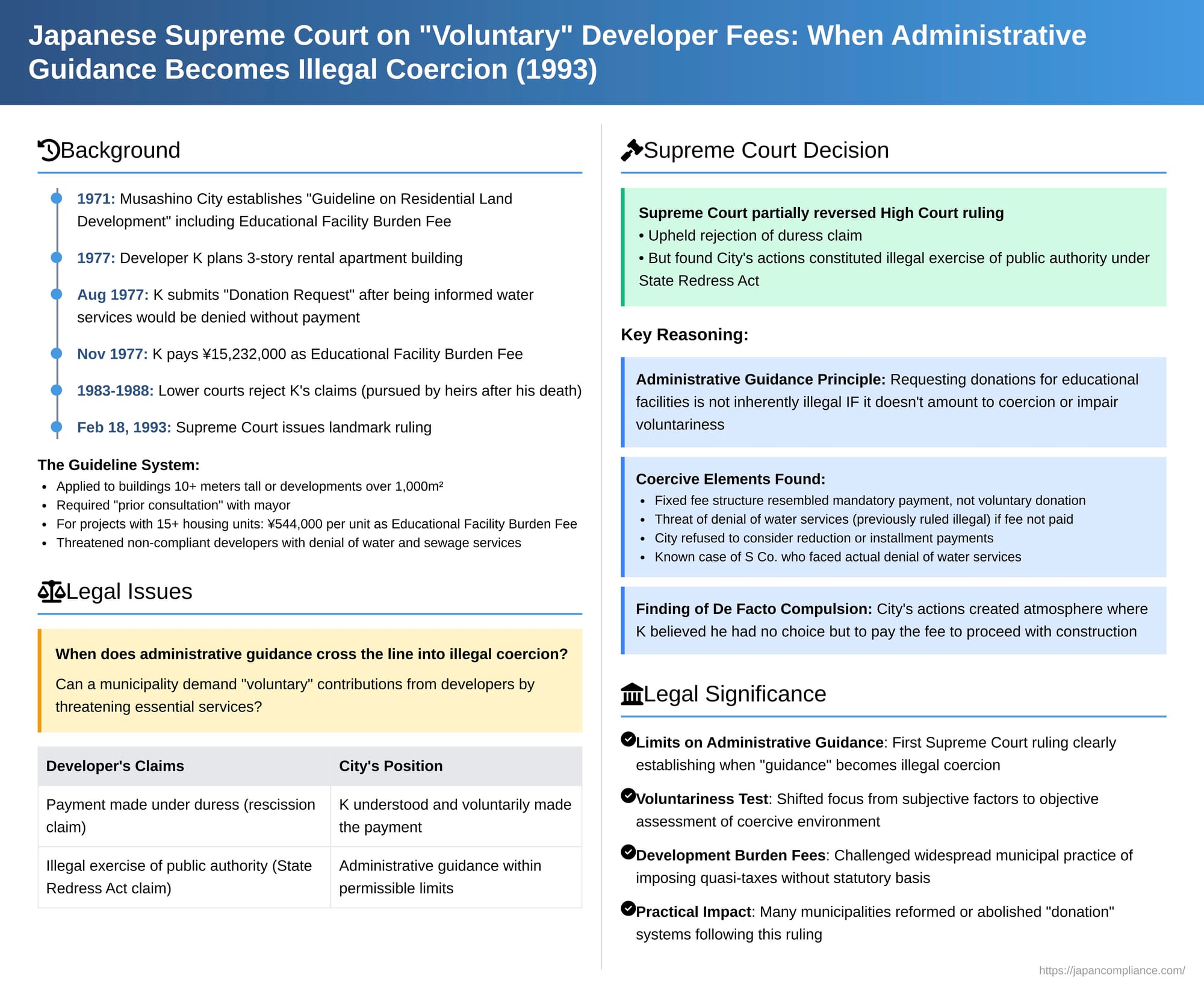

This landmark 1993 Supreme Court decision grapples with the fine line between permissible administrative guidance (gyōsei shidō) and illegal coercion by local governments, particularly in the context of "voluntary" financial contributions sought from property developers. The case involved the appellants, K. T. and eleven others (hereafter X), and the appellee, Musashino City (hereafter Y or "the City"). X sought the return of an "educational facility burden fee" paid by the deceased Mr. K. T. (hereafter K) to Y, arguing the payment was made under duress or, alternatively, that the City's demand for the fee constituted an illegal exercise of public authority.

The Rise of Development Burdens in Musashino City

The backdrop to this dispute was the rapid urban development experienced by many Japanese cities, including Musashino City, starting around 1969. A surge in apartment construction led to a host of problems for existing residents, such as obstruction of sunlight, television signal interference, and construction noise. More critically, this rapid growth strained public infrastructure, leading to shortages in schools, nurseries, and traffic safety facilities, thereby placing significant pressure on the City's administration and finance.

In response, Musashino City, aiming to protect the living environment from what it perceived as the negative impacts of unchecked development, established the "Musashino City Guideline on Residential Land Development, etc." (hereafter "the Guideline") on October 1, 1971. This Guideline was created after consultation with the City council's general committee and was intended to provide administrative guidance to developers undertaking projects of a certain scale.

Key provisions of the Guideline relevant to this case included:

- Applicability: The Guideline applied to residential land development projects of 1,000 square meters or more, or the construction of medium-to-high-rise buildings 10 meters or taller.

- Prior Consultation: Developers were required to engage in "prior consultation" (jizen kyōgi) with the mayor and undergo an examination of their plans. This involved public disclosure of project details, provision for public facilities and their costs, and addressing issues like sunshine obstruction.

- Consents and Compensation: For projects potentially affecting the surrounding area, developers had to obtain prior consent from concerned parties and assume responsibility for compensating any damages caused.

- Infrastructure Provision: Developers were mandated to construct roads within the project area to specified standards (width, drainage, gutters) and provide them to the City free of charge. For developments over 3,000 square meters, a certain percentage of land had to be allocated for parks and green spaces. Water and sewage facilities were to be constructed by the City at the developer's expense, or by the developer according to City instructions, and then transferred to the City without charge.

- Educational Facility Burden Fee: For construction projects involving 15 or more housing units, developers were required to provide school land to the City free of charge based on City standards, or bear the land acquisition costs, as well as the construction costs for these facilities. The monetary contribution for this was termed the "educational facility burden fee." For projects of 15 to 113 units, this fee was set at 544,000 yen per unit.

- Other Facilities: Developers had to install and maintain fire safety facilities, garbage collection and processing facilities, streetlights, and secure parking, as per City instructions.

- Sanctions for Non-Compliance: Crucially, the Guideline stipulated that the City "may not provide necessary facilities such as water and sewage, or other cooperation" to developers who did not comply with the Guideline.

The City implemented the Guideline through a process involving the Musashino City Residential Land Development, etc. Examination Committee. Developers would first consult with the relevant City department, then submit a "Business Plan Approval Application" along with an "Educational Facility Burden Fee Donation Request" to the mayor. If the Examination Committee approved the plan (after further administrative guidance if requirements weren't met), the mayor would issue a "Business Plan Approval Certificate". Within 20 days of this approval, the developer was to pay the educational facility burden fee.

Musashino City also coordinated with Tokyo Metropolitan Government agencies. The City requested these agencies (which handled building permit applications) to consult with Musashino City regarding the Guideline before accepting such applications. The Tokyo agencies agreed, establishing a practice where developers needed to submit the City's Approval Certificate with their building permit application to the Metropolis.

This system, bolstered by strong citizen support and cooperation from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, became increasingly entrenched over the years. Developers found it practically difficult to proceed with projects if they did not adhere to the Guideline. Consequently, most developers complied, and those who couldn't effectively had to abandon their projects. The educational facility burden fee, in particular, saw no instances of reduction, deferred payment, or installment payments, with one notable exception involving S Construction Co. (hereafter "S Co."), which eventually had to promise payment of an equivalent sum, explicitly as a donation, in a court settlement.

The Case of K and the Disputed Payment

In May 1977, K planned to construct a three-story rental apartment building on land in Musashino City, co-owned with his wife (appellant K. T.) and two sons (appellants R. T. and S. T.). He entrusted negotiations with the City concerning the Guideline to Mr. K, the representative of N Architectural Design Office.

K was informed by his representative that he would have to "donate" 15,232,000 yen as an educational facility burden fee according to the Guideline. K was already obligated under the Guideline to provide parkland to the City free of lease, donate land for roads, donate park playground equipment, and bear the cost of installing a fire cistern. Having already paid substantial taxes, K was strongly dissatisfied with the additional demand for a large educational facility burden fee.

During the prior consultation with the City, K, through employees of the N Architectural Design Office, pleaded with the responsible City official for a reduction, deferred payment, or installment plan for the burden fee. The official refused, stating there was "no precedent".

Subsequently, K's representative, who was aware of the Guideline's procedures, the burden fee clause, and its operational reality, advised K that if he did not offer to donate the educational facility burden fee as per the Guideline and obtain the Business Plan Approval, the City would deny water and sewage services, making it impossible to build the apartment. Feeling he had no alternative, K submitted a "Donation Request" to the City on August 5, 1977, offering to donate 15,222,000 yen (though the Guideline calculation was 15,232,000 yen), along with his Business Plan Approval Application. The plan was approved by the Examination Committee on August 25, and building permission was granted on October 25, 1977.

Still unconvinced about the high burden fee, K personally appealed to City officials for reduction, deferral, or installments but was again refused due to lack of precedent. On November 2, 1977, he paid 15,232,000 yen to the City.

Litigation Path and Lower Court Decisions

K (whose claim was later pursued by X after his death) sued Musashino City for a refund of the burden fee. The primary claim was that the "donation" was made under duress, and thus the declaration of intent to donate should be rescinded. The first instance court (Hachioji Branch of the Tokyo District Court, February 9, 1983) dismissed this claim, finding that K had not been in a state of fear.

X appealed to the Tokyo High Court, adding an alternative (preliminary) claim for damages under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Redress Act. This claim asserted that the City's administrative guidance demanding the burden fee was an illegal exercise of public authority. The High Court, in its judgment on March 29, 1988, also dismissed both claims. It found that K seemed to have paid the burden fee with a degree of understanding at the time, and the City's administrative guidance did not exceed permissible limits. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Judgment

The Supreme Court's decision on February 18, 1993, marked a significant moment in the jurisprudence of administrative guidance and developer contributions.

1. Duress Claim:

The Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' rejection of the duress claim. It found the High Court's factual findings and judgment on this point to be justifiable based on the evidence presented and saw no error in its decision.

2. State Redress Claim (The Reversal):

The crucial part of the Supreme Court's ruling was its handling of the State Redress claim. It overturned the High Court's decision to dismiss this claim and remanded it back to the High Court for further deliberation.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Legality of Requesting Donations via Administrative Guidance:

The Court began by stating a general principle: requesting a developer to pay a donation to fund educational facilities, as administrative guidance, is not inherently illegal, provided it does not amount to coercion or otherwise impair the developer's voluntariness. This acknowledged the potential legitimacy of seeking contributions if truly voluntary. - Scrutiny of Musashino City's Guideline and its Operation:

However, the Court then critically examined the nature and application of Musashino City's Guideline:- Non-Statutory Basis: The Guideline was not based on any specific law but was an internal standard established by the City for conducting administrative guidance.

- Embedded Sanctions: Despite its non-statutory nature, the Guideline threatened sanctions, such as the refusal of water supply contracts, for non-compliance.

- Compulsory Nature of the Fee: The educational facility burden fee was defined with such specificity (a fixed amount per housing unit) that it resembled an assigned obligation or a mandated payment rather than a voluntary donation. The wording made it difficult to see it as a purely voluntary contribution.

- Illegality of the Sanction: The threatened sanction of denying water supply was, in itself, illegal. The Court referenced the Water Supply Act (Article 15, Paragraph 1) and a prior Supreme Court criminal case (1989) which found such denial to be unlawful. If implemented, this sanction would render an apartment building unusable for residential purposes, thereby frustrating the entire purpose of the construction project.

- Operational Reality and Coercive Atmosphere: At the time K was pressured to pay, the operational reality was that developers unable to comply with the Guideline were effectively forced to abandon their development projects. The only developer who had defied the Guideline, S Co., had indeed faced denial of water supply and sewage system access by the City. This S Co. case was widely reported in the newspapers. Furthermore, the mayor of Musashino City was later convicted for violating the Water Supply Act in connection with denying water to an apartment building completed by S Co. without adhering to all Guideline procedures.

- City's Refusal to Negotiate: When K pleaded with City officials for a reduction or deferral of the burden fee, their response was an outright refusal based on "no precedent". The Supreme Court viewed this attitude as completely inconsistent with an administration genuinely seeking a voluntary donation; it did not reflect any understanding that the payment was supposed to be at the developer's discretion.

- Finding of De Facto Compulsion and Illegality:

Based on the Guideline's text and its actual operation, the Supreme Court concluded that Musashino City was, at the time, attempting to enforce compliance with the Guideline by leveraging the threat of illegal sanctions (specifically, denial of water supply contracts), which, if carried out, would make the completion of an apartment building's purpose factually impossible.The City's demand for the educational facility burden fee from K, combined with the officials' inflexible refusal to consider any reduction or alternative payment arrangements, was deemed sufficient to make K believe that if he did not pay the prescribed amount, he would be denied water and sewage services. This, the Court found, effectively compelled K to comply with the administrative guidance if he wished to proceed with building his apartment. It was, in essence, a de facto compulsion to pay the educational facility burden fee.The Court acknowledged the City's stated purpose for the Guideline – to protect the living environment of Musashino citizens from "disorderly development" – and that it enjoyed considerable public support. However, even considering these factors, the City's actions in demanding the burden fee from K exceeded the permissible limits of administrative guidance, which should be based on securing voluntary contributions. Therefore, the City's conduct constituted an illegal exercise of public authority under the State Redress Act.

The Supreme Court found the High Court's contrary judgment on this point to be based on an erroneous interpretation and application of the law, an error that clearly affected its conclusion. The portion of the High Court's judgment dismissing X's preliminary claim for damages was therefore reversed, and the case was remanded for further proceedings on this specific claim.

Significance and Implications of the Ruling

This 1993 Supreme Court decision was a landmark because it was one of the first instances where the highest court explicitly found that a municipality's demand for a monetary payment, based on a non-legally binding "development guideline," could constitute an illegal exercise of public authority, giving rise to state liability.

Development burden fees had become a common feature in many Japanese municipalities since the 1960s, particularly in urban and suburban areas experiencing rapid growth. These guidelines often included provisions requiring developers to provide land for public facilities free of charge or to pay sums of money, variously termed "development burden fees" or "development cooperation money," to help fund the infrastructure needed to support the new populations brought by development. The "educational facility burden fee" in Musashino City was specifically aimed at securing land or funds for school facilities to accommodate the expected increase in students.

The legality of such fees had long been debated. They raised concerns about potential conflicts with provisions of the Local Finance Act, such as Article 4.5 (which generally prohibits "assigned donations" that are not voluntary) and Article 27.4 (which prohibits municipalities from improperly shifting expenses they should bear onto residents). They also intersected with the Local Tax Act, which has provisions for a specific "residential land development tax" (Article 703.3). However, none of these laws explicitly forbid genuinely voluntary contributions. Thus, the central legal question often revolved around the voluntariness of the payment: did the administrative guidance used to solicit the fee cross the line into coercion? This Supreme Court judgment decisively found that, in Musashino City's case, this line had been crossed. (The case was reportedly settled upon remand to the High Court.)

The mechanism of such "guideline-based administrative guidance" often involved leveraging statutory powers. While guidelines themselves are internal administrative standards without the force of law, making developer contributions theoretically voluntary, in practice, their observance was frequently linked to the granting of necessary legal permissions, such as building permits under the Building Standards Act or development permits under the City Planning Act. Some guidelines explicitly included sanctions for non-compliance, such as denying water supply (as in this case) or publicizing the names of non-compliant developers, effectively presenting developers with a choice: pay the "voluntary" contribution or abandon the project.

In Musashino City, the system was particularly effective because failure to pay the educational facility burden fee meant the developer would not receive the "Business Plan Approval Certificate" from the mayor. Due to an understanding between Musashino City and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (which had the authority for issuing building permits), an application for a building permit in Tokyo for a Musashino City project would not be accepted without this certificate. This created a powerful incentive for compliance, backed by the ultimate threat of denying water and sewage services, a threat that had been actualized in the case of S Co.

A key aspect of the Supreme Court's reasoning was its approach to determining "voluntariness." An earlier Supreme Court case in 1985, concerning the withholding of building permits, had placed significant emphasis on the developer's subjective attitude, particularly whether they had clearly and sincerely expressed an intention not to cooperate with the administrative guidance. In contrast, the 1993 Musashino City judgment appeared to focus more on the objective characteristics of the administrative guidance itself: the specific wording of the Guideline, the way it was implemented in practice, and, critically, the use of illegal sanctions as a backdrop to compel compliance.

In K's case, he had pleaded for a reduction but had not outright refused to pay. Under a purely subjective test like that in the 1985 case, the lower court's finding that he had "understood" and "accepted" the payment might have seemed arguable. However, the 1993 Supreme Court looked at the totality of the circumstances – especially the credible threat of an illegal denial of essential services (water and sewage), a threat made real in other local cases – and concluded that this created a coercive environment that amounted to de facto compulsion, regardless of whether K had made a formal, explicit refusal. The psychological pressure generated by the objective circumstances was paramount. This suggests that while an explicit refusal of administrative guidance is an important factor, it is not necessarily the sole determinant of whether a payment was truly voluntary.

The issue of development burden fees and the use of administrative guidelines to impose them remains complex. While some aspects of such guidelines (like those concerning sunlight access or detailed local planning) have subsequently been incorporated into formal legislation (e.g., the Building Standards Act or City Planning Act), and overtly illegal sanctions like water supply denial have been clearly proscribed, the broader policy debate on how to fund development-related infrastructure continues. Musashino City itself abolished the educational facility burden fee in 1978. For many municipalities, relying on non-binding guidelines for such financial impositions remains legally precarious, with many legal scholars suggesting that comprehensive legislative solutions are needed if such contributions are to be legitimately and systematically collected.

This Supreme Court ruling stands as a critical reminder of the limits of administrative power, emphasizing that administrative guidance, however well-intentioned its ultimate goals, must respect the voluntariness of the citizen and cannot rely on illegal threats or create an atmosphere of de facto compulsion to achieve its objectives.