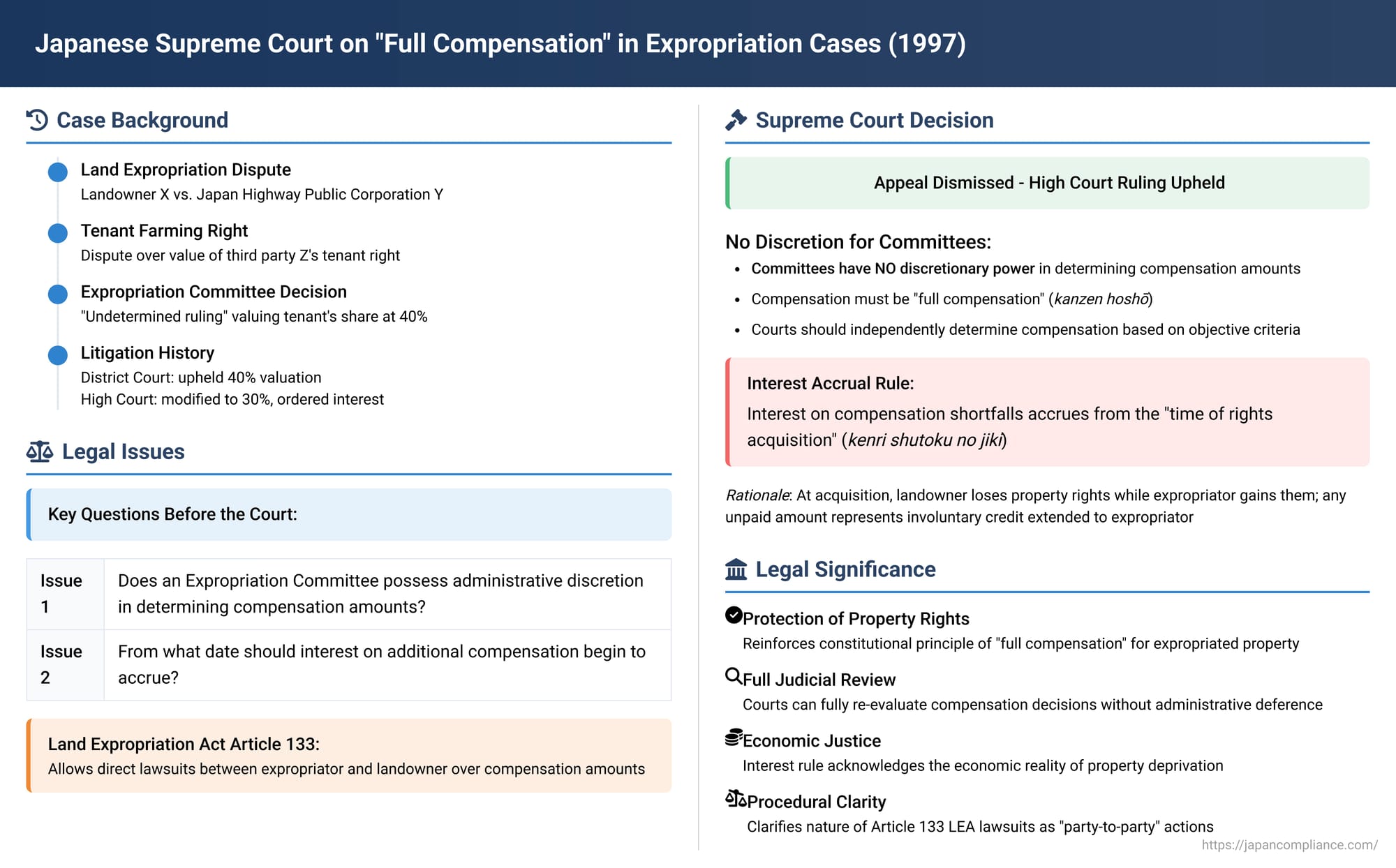

Japanese Supreme Court on "Full Compensation" in Expropriation Cases: No Discretion for Committees, Interest from Rights Acquisition

Date of Judgment: January 28, 1997

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

On January 28, 1997, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case concerning a claim for an increase in expropriation compensation. This decision grappled with core issues fundamental to property rights and administrative law: the precise meaning of "full compensation" for expropriated land, the extent of discretion (if any) held by Expropriation Committees in determining compensation amounts, and the critical question of when interest begins to accrue on any shortfall in that compensation. The ruling robustly reinforces the principle that landowners must be made whole, clarifies the standards for judicial review of compensation awards, and provides important guidance on the calculation of interest.

I. Factual Background and Procedural History

The case originated from the expropriation of land owned by an individual, X, by Y, the Japan Highway Public Corporation (a public entity responsible for highway construction and management).

The Expropriation and a Complicating Factor

Y initiated proceedings to expropriate a parcel of land belonging to X for a public project. A significant complication arose due to a dispute over the existence and, critically, the value of a tenant farming right (kosakuken) allegedly held by a third party, Z, on the subject land. The valuation of this tenancy right would directly impact the net compensation payable to X, the landowner.

The Expropriation Committee's Ruling

The local Expropriation Committee, tasked with determining the initial compensation, issued what is known as an "undetermined ruling" (fumei saiketsu). This type of ruling can be made when there are uncertainties regarding specific rights attached to the land or the precise distribution of compensation among multiple interested parties. In its ruling, the Committee assessed the value of Z's tenant farming right as representing a 40% share of the total compensation attributable to the land.

X's Lawsuit Seeking Increased Compensation

Dissatisfied with the Committee's determination, X filed a lawsuit under Article 133 of the Land Expropriation Act (LEA). X argued that the 40% share attributed to Z's alleged tenancy right was excessive and that a 20% share would be appropriate. Consequently, X sought a judicial redetermination that would increase the net compensation payable to X, along with an order for Y to pay the resulting difference.

Lower Court Rulings

The case proceeded through the lower courts with differing outcomes:

- District Court: The court of first instance sided with the Expropriation Committee. It found the Committee's assessment of the tenancy right's share at 40% to be reasonable, or at least within the Committee's legitimate range of discretion, and consequently dismissed X's claim for increased compensation.

- High Court: On appeal, the High Court reached a different conclusion. It determined that a 30% share for the tenant farming right was the appropriate valuation. The High Court, therefore, modified the Expropriation Committee's compensation award to reflect this lower valuation for Z's interest (and a correspondingly higher share for X). It ordered Y to pay X the shortfall that resulted from this recalculation. Furthermore, the High Court ordered Y to pay interest on this shortfall amount, with interest commencing from the day after the formal complaint was served upon Y.

Y's Appeal to the Supreme Court

Y, the Japan Highway Public Corporation, along with Z as an auxiliary participant supporting Y's position, appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

II. Key Issues Before the Supreme Court

The appeal brought two principal legal questions to the forefront for the Supreme Court's consideration:

- Discretion of the Expropriation Committee: Does an Expropriation Committee possess administrative discretion in determining the monetary amount of compensation for expropriated land? If so, this would imply that a court's power to review and alter the Committee’s award is limited to instances where the Committee has clearly abused its discretion or acted outside the bounds of its authority. Y argued that the High Court had failed to properly consider this alleged discretionary power.

- Accrual of Interest on Compensation Shortfalls: If a court determines that the compensation awarded by the Committee was insufficient and orders an increase, from what specific date should interest on that additional sum begin to accrue? Y contended that, because it had already deposited funds with a legal affairs bureau relating to the disputed tenant farming right (as per the "undetermined ruling"), it should not be held liable for interest on any court-ordered increase payable to X, at least not until the court's judgment mandating such an increase became final and conclusive.

III. The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the High Court's decision in favor of X, and in doing so, provided critical clarifications on the law of expropriation compensation.

A. The Principle of "Full Compensation" and No Discretion for the Committee

The Court began its reasoning by emphasizing the fundamental nature of compensation in expropriation cases.

- Constitutional Mandate for "Full Compensation": The judgment reiterated the established principle that compensation under the Land Expropriation Act must be "full compensation" (kanzen hoshō). This principle, rooted in the constitutional protection of property rights, aims to restore the expropriated landowner to a financial position equivalent to the one they held before their property was taken for public use. The Court referenced its own earlier landmark decision (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, October 18, 1973), which articulated that monetary compensation must be sufficient to enable the landowner to acquire equivalent replacement property in the same vicinity.

- Objective Determination of Value: While the LEA employs terms such as "fair value" (soutou na kakaku) (e.g., Article 71 of the LEA) to describe the standard for compensation, and these terms are inherently indeterminate legal concepts, the Court stressed that the actual amount of compensation must be determined objectively. This determination should be based on common experience and prevailing social norms.

- No Discretionary Power for the Committee: In a clear and direct pronouncement, the Supreme Court explicitly ruled that Expropriation Committees do not possess discretionary power when it comes to deciding the scope or the monetary amount of compensation. The PDF commentary accompanying this case highlights that this denial of discretion is supported by the constitutional basis of compensation rights and the fact that these legal challenges take the form of party-to-party lawsuits rather than judicial review of administrative discretion. The commentary also notes that courts are frequently tasked with monetary valuations in other contexts, such as damages in tort cases.

- Role of the Court in Adjudicating Compensation: Consequently, in a lawsuit brought under Article 133 of the LEA, the reviewing court's function is not merely to scrutinize whether the Expropriation Committee abused any supposed discretion. Instead, the court is tasked with independently determining the objectively "just compensation" amount. This judicial determination is to be made based on the evidence presented during the court proceedings, looking at the circumstances as they existed at the time of the Committee’s original ruling. If the court's independently calculated just compensation amount differs from the amount awarded by the Committee, the Committee's award is deemed unlawful to the extent of that difference, and the court's judgment will establish and confirm the correct, legally mandated compensation figure.

B. Accrual of Interest on Compensation Shortfalls

The Supreme Court then addressed the issue of when interest should begin to accrue if the court awards a higher compensation amount than the Committee did.

- Purpose of Article 133 Lawsuits: The Court noted that lawsuits under Article 133 LEA, while challenging aspects of the Committee's compensation ruling, are ultimately aimed at definitively resolving compensation disputes between the expropriator and the affected parties (such as landowners or those holding other compensable rights). The overarching goal is to ensure the realization of just and fair compensation.

- Significance of the "Time of Rights Acquisition": When a court, in such a lawsuit, finds that the compensation awarded by the Committee was too low, its judgment effectively determines the amount that should have been paid by the "time of rights acquisition" (kenri shutoku no jiki). This is the specific date on which the expropriator legally acquires the rights to the expropriated land. At this precise moment, the landowner is deprived of their rights to the land and its use, while the expropriator simultaneously gains these rights and the ability to use the land for its project.

- Landowner's Entitlement to Interest: Given this reciprocal shift in rights and utility, the Supreme Court reasoned that the landowner is entitled not only to the principal difference between the court-determined just compensation and the Committee's original, lower award but also to interest on that unpaid difference. This interest, the Court held, accrues from the "time of rights acquisition" until the date the shortfall is fully paid by the expropriator. The applicable interest rate is the statutory rate provided under the Civil Code (which, at the time of this judgment, was 5% per annum). The PDF commentary notes that this conclusion regarding the starting point for interest is substantively appropriate, regardless of whether one adopts the formative action theory or the payment action theory for the nature of the suit itself.

C. Application to the Specifics of the "Undetermined Ruling" and Deposit

Y, the expropriator, had argued that its deposit of funds related to Z's disputed tenancy right (made under the provisions of the LEA concerning "undetermined rulings") should preclude the accrual of interest on any increased amount found due to X, at least until the High Court's judgment became final.

- The Supreme Court rejected this argument. It clarified that the lawsuit, from X's perspective, concerned the correct amount of compensation due to X for X's "underlying land rights" (sokochi-ken)—that is, the value of the land after properly accounting for the actual (and correctly valued) tenant farming right of Z. The High Court had found that the Expropriation Committee's initial ruling had effectively undervalued X's share of the total compensation by over-allocating to Z's disputed right.

- The shortfall thus identified was an amount directly owed to X. The payment obligation for this shortfall, the Court reasoned, was distinct from any funds that Y might have deposited concerning Z's claim. Therefore, the deposit made by Y in relation to Z's uncertain claim did not absolve Y of its obligation to ensure X received the full and correct compensation for X's own rights from the moment those rights were acquired by Y.

- As such, interest on the shortfall owed to X was correctly deemed to accrue. The High Court had ordered interest to commence from the day after the complaint was served on Y. Since the "time of rights acquisition" would typically be earlier than the service of the complaint, the High Court's order regarding the starting date for interest was not disadvantageous to Y and was therefore upheld by the Supreme Court.

IV. The Nature of Lawsuits Challenging Compensation Amounts

This case was initiated under Article 133 of the Land Expropriation Act, and such lawsuits possess a distinct procedural character within Japanese administrative law.

- Unlike typical administrative litigation where a plaintiff might sue to revoke a decision made by an administrative agency (e.g., the Expropriation Committee), these compensation lawsuits under Article 133 are conducted directly between the expropriating entity (the "project undertaker," such as Y in this case) and the landowner or other parties holding compensable interests in the land (like X, or potentially Z if their rights were established). The Expropriation Committee is not the defendant in disputes over the amount of compensation.

- These legal actions are generally understood in legal doctrine as "formal party suits" (keishiki-teki tōjisha soshō). This category of suit is recognized under Article 4 of Japan's Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA). The term signifies that while the dispute originates from an administrative process or decision (here, the Committee's ruling on compensation), the ensuing lawsuit takes on the characteristics of an ordinary civil suit between two parties who are asserting their respective rights and obligations under public law.

- For many years, there has been a nuanced academic and, to some extent, judicial debate concerning the precise legal classification of these Article 133 LEA lawsuits:

- Formative Action Theory (keisei soshō setsu): This theory proposes that the primary aim of the lawsuit is to formally change or modify the Expropriation Committee's ruling on compensation. If a plaintiff (e.g., a landowner seeking more money) is successful under this theory, they would obtain a court judgment that legally alters the Committee's original award. Following such a judgment, they might then need to take a separate procedural step to demand actual payment based on the newly modified award, although it is often contemplated that both the claim for modification and the claim for payment could be combined in a single proceeding.

- Payment/Declaratory Action Theory (kyūfu (kakunin) soshō setsu): This alternative theory views the lawsuit in more direct terms. If a landowner seeks an increase in compensation, the suit is directly a claim for the payment of the additional amount deemed due. Conversely, if the expropriating entity were to challenge the Committee's award as being too high, the suit might be characterized as one seeking a declaration that a lesser amount is owed. This approach sees the court as directly adjudicating and determining the monetary obligation between the parties. The PDF commentary suggests that this payment/declaratory action theory is the more appropriate interpretation of the current law. One reason cited is that requiring a separate payment claim after a formative judgment seems unnecessarily circuitous. It also argues that the concept of "public authority" or "binding force" (kōtei-ryoku) of the administrative decision on compensation is not an impediment, as the law specifically carves out compensation disputes from typical administrative review processes.

- In its January 1997 judgment, the Supreme Court did not explicitly take a side to definitively settle this long-standing doctrinal debate. It upheld the High Court's judgment, which had, in effect, ordered direct payment of the increased compensation amount to X. Legal commentators, as reflected in the provided PDF, note that the practical differences between these competing theories are often quite minimal, primarily influencing the formal wording used in the plaintiff's statement of claim and in the dispositive part of the court's judgment. There is a widely held view among practitioners and academics that courts should adopt a flexible approach, interpreting the claims and the law in a way that ensures substantive justice for the parties involved, rather than allowing procedural technicalities to obscure the merits of the case. This is particularly pertinent because the Land Expropriation Act itself does not offer perfectly clear guidance on this specific procedural point.

V. Implications of No Discretion and Interest Rules

The Supreme Court's pronouncements in this case carry significant implications for the protection of property rights in the context of expropriation.

- No Discretion for Committees Means Full Judicial Review: The Court's unequivocal stance that Expropriation Committees lack discretion in the determination of compensation amounts is of paramount importance. It ensures that landowners are entitled to an objective, judicial determination of what constitutes "full compensation." Their claims for compensation are reviewable by a court on their full merits, not merely under a deferential standard of whether the administrative body abused its discretion. This approach aligns with the understanding that the right to compensation for expropriated property is a fundamental, constitutionally protected right. Its valuation, therefore, should not be subject to administrative leeway or subjective judgment but should be based on objective criteria that a court can fully re-evaluate. The fact that challenges to compensation amounts proceed as "party suits" between the expropriator and the affected individual, rather than as actions to annul an administrative disposition, further supports this model of comprehensive judicial review.

- Interest from Rights Acquisition Upholds "Full Compensation": The rule mandating that interest on any compensation shortfall accrues from the date the expropriator legally acquires rights to the land is vital for ensuring that the compensation paid is indeed "full". This rule acknowledges the economic reality that from the moment of rights acquisition, the landowner is deprived of their property, its use, and any income or benefits it might have generated. Simultaneously, the expropriator gains the right to use the land for its purposes. If the full and just amount of compensation is not paid on that date, the landowner is, in effect, involuntarily extending credit to the expropriator for the unpaid portion. The interest payment serves to compensate the landowner for this loss of use of funds (the time value of money) during the period of delayed payment, thereby making the ultimate compensation received more truly "full."

VI. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision of January 28, 1997, in this expropriation compensation case, delivers a clear and firm message on the rights of landowners. It robustly reinforces the constitutional and statutory principle of "full compensation," ensuring that those whose property is taken for public use are made financially whole.

By definitively clarifying that Expropriation Committees lack any administrative discretion in determining the monetary amount of compensation, the judgment affirms that such awards are subject to full and objective re-evaluation by the courts. Furthermore, the ruling on the accrual of interest—that it commences from the date of rights acquisition—is crucial for ensuring that the compensation is truly comprehensive and accounts for delays in payment. While some finer points of procedural theory regarding the nature of these lawsuits may continue to be debated in academic circles, this Supreme Court judgment prioritizes substantive justice and the effective realization of constitutionally protected property rights in the face of state expropriation.