Japanese Supreme Court on Building Registration and Tenant Rights: The 1966 Grand Bench Decision

Date of Judgment: April 27, 1966

Case Name: Building Removal and Land Surrender Claim

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Introduction

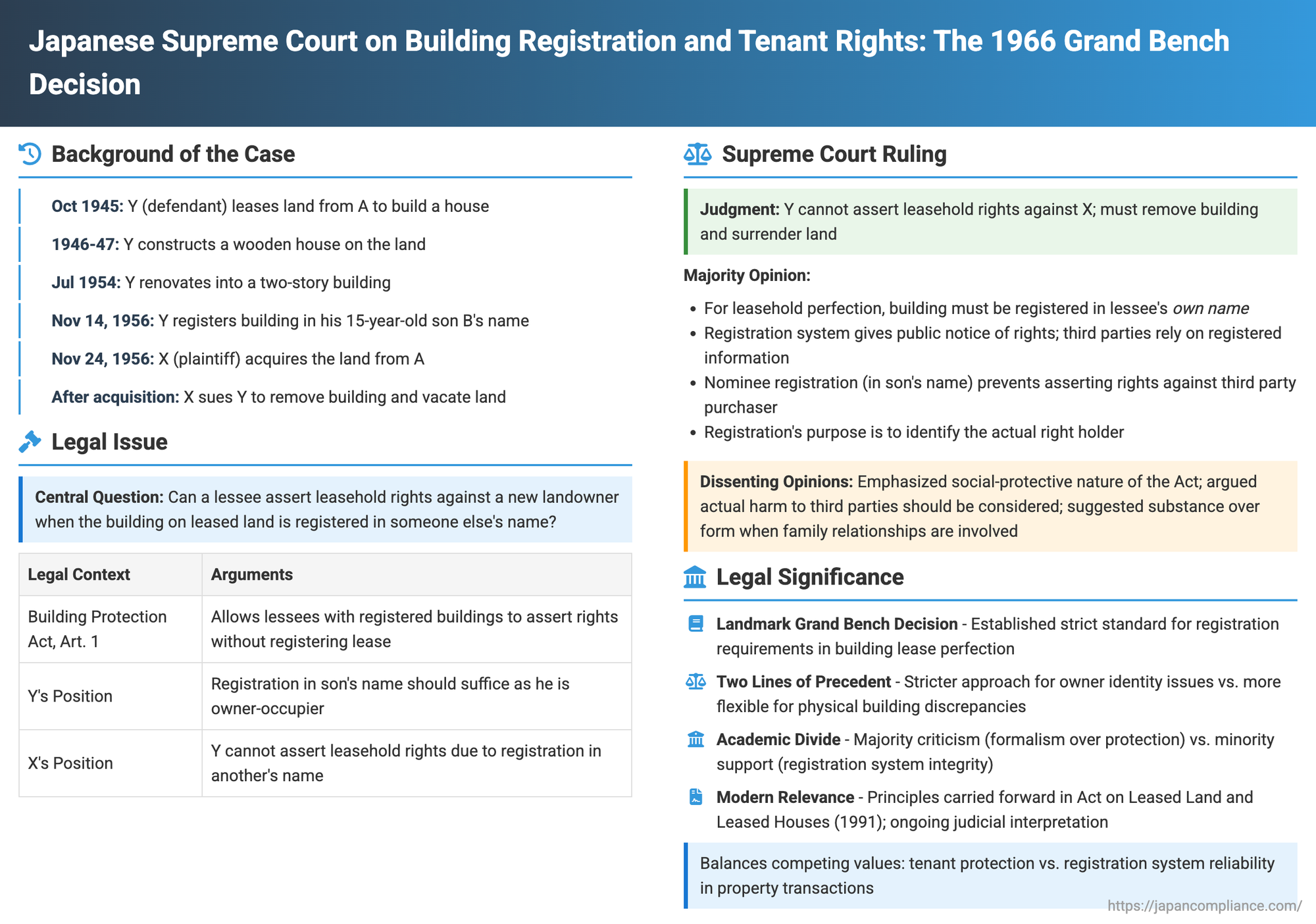

In Japan's property law landscape, the registration system plays a crucial role in determining rights and protecting transactions. A significant judgment by the Supreme Court's Grand Bench on April 27, 1966, delved into the intricacies of this system, specifically concerning a lessee's ability to assert their leasehold rights against a new landowner when the building on the leased land was registered in someone else's name. This case highlights the delicate balance between protecting tenants and ensuring the reliability of the public registration system.

The Factual Background: A Lease, a Building, and a Nominee Registration

The dispute originated from a series of events beginning in post-war Japan:

Around late October 1945, an individual, Y, entered into a lease agreement with A, the owner of a parcel of land in Matsuyama City, specifically identified as Lot 28 in Kitaebisu-chō (hereinafter "Land K"). The purpose of this lease, which had no specified duration, was for Y to construct and own a building on Land K. [cite: 1]

Following this agreement, Y proceeded to build a wooden, single-story house on Land K. This construction took place between 1946 and the spring of 1947. Several years later, in July 1954, Y undertook a significant renovation, expanding the house into a two-story structure, which we will refer to as "Building O." [cite: 1]

A pivotal moment occurred on November 14, 1956. Y, who was facing stomach surgery and reportedly concerned about his long-term health, decided to register the ownership of Building O. Believing it would simplify matters in the future, Y registered the building in the name of his eldest son, B. [cite: 1] At the time, B was 15 years old and living with Y in Building O. [cite: 1] This registration was done by Y without B's explicit permission, under the assumption that B's name on the title would prevent later complications. [cite: 1]

Shortly thereafter, the ownership of Land K changed hands. On November 24, 1956, a company, X, acquired Land K from A through a property exchange. [cite: 1] X completed the registration of this ownership transfer on November 27, 1956. [cite: 1]

Upon acquiring the land, X initiated legal proceedings against Y. X's claim was that Y could not assert his leasehold rights over Land K against X. [cite: 1] The core of X's argument was that Y had failed to properly perfect his leasehold rights because Building O, situated on the leased land, was not registered in Y's own name. [cite: 1] Consequently, X demanded that Y remove Building O and surrender possession of Land K, asserting that Y's occupation of the land was unlawful as against X. [cite: 1]

The case proceeded through the lower courts, where Y initially found success. However, X, being dissatisfied with the lower court's decision to dismiss its claim, appealed to the Supreme Court. [cite: 1]

The Central Legal Question Before the Supreme Court

The primary legal issue that the Supreme Court had to resolve was:

Can a lessee of land (Y), who constructed a building (Building O) on that land for the purpose of ownership, but registered the said building in the name of another person (his son, B), validly assert his land leasehold rights against a third party (X) who subsequently acquired ownership of the land? [cite: 1]

This question hinged on the interpretation of Article 1 of the then-operative Building Protection Act (建物保護ニ関スル法律 - Tatemono Hogo ni Kan suru Hōritsu). [cite: 1]

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, in a decision that would become a significant precedent, overturned the lower court's judgment in favor of Y. The Court ruled in favor of X, ordering Y to remove Building O and vacate Land K.

The Majority's Reasoning: Strict Adherence to Registration in Lessee's Own Name

The majority opinion meticulously laid out its reasoning, centered on the purpose and requirements of the Building Protection Act and the broader principles of Japanese property registration law.

- Purpose of Article 1 of the Building Protection Act:

The Court began by explaining the function of Article 1 of the Building Protection Act. This provision stipulated that if a lessee, holding a lease for the purpose of owning a building, possesses a registered building on that land, they can assert their leasehold rights against third parties even if the lease itself is not registered. [cite: 1] The rationale underpinning this rule, the Court clarified, is that a party engaging in a transaction involving such land can infer the existence of the lessee's right to use the land (the leasehold) by observing the registered building and its registered owner. [cite: 1] The building's registration serves as a form of public notice, substituting for the registration of the leasehold itself. - Requirement of Registration in the Lessee's Own Name:

Crucially, the Court interpreted this to mean that the lessee must have the building registered in their own name to benefit from this statutory protection. [cite: 1] Only when the building is registered in the actual lessee's name can third parties reliably infer that the registered owner of the building possesses a corresponding leasehold right to the land beneath it. - Consequences of Nominee Registration:

The Court found that Y, by his own volition, had registered Building O in his son B's name. [cite: 1] Even if B was Y's minor son, lived with him, and the registration was motivated by Y's personal circumstances (health concerns and a desire to avoid future complications), the registration was undeniably in B's name, not Y's.

The Court stated that such a nominee registration prevents the lessee (Y) from asserting leasehold rights against a third party (X). [cite: 1] The reasoning was stark: if a building is registered in another person's name, the true owner cannot even assert their ownership of the building against a third party who relies on the registry. [cite: 1] Since the Building Protection Act's mechanism presupposes that the lessee has a validly registered ownership of the building which can be asserted against third parties, a nominee registration fails this fundamental prerequisite. [cite: 1] In such cases, the lessee is not "worthy" of the Act's protection. [cite: 1] - The Nature and Purpose of the Registration System:

The Court emphasized that the property registration system is designed to provide a public method of notification (公示 - kōji) for changes in real rights (物権変動 - bukken hendō) and to protect the interests of third parties involved in transactions. [cite: 1] As a general principle, third parties are entitled to rely on the information recorded in the public registry to ascertain who the right holders are. [cite: 1]

In this specific case, the registration of Building O in B's name would not lead a third party like X to infer that Y was the actual owner of the building and, by extension, the holder of the leasehold rights for Land K. [cite: 1] To grant Y the ability to assert his leasehold rights under such circumstances would, in the Court's view, unfairly prejudice the interests of third parties who rely on the integrity of the registry. [cite: 1] - Registration Must Reflect Substantive Rights:

For a registration to have "perfection power" or "oppositional force" (対抗力 - taikōryoku) against third parties, it must, at a minimum, correspond to the actual, substantive state of rights. [cite: 1] A registration in the name of someone who is not the true substantive right holder (like B, in this case, concerning Y's intended leasehold assertion) is considered an invalid registration because it does not align with the true rights. [cite: 1] Such an invalid registration cannot give rise to perfection power. [cite: 1] - Impossibility of "Correcting" the Defective Registration:

The Court further reasoned that the registration in B's name and a hypothetical (correct) registration in Y's name (as the true owner and lessee) could not be considered identical. [cite: 1] The defect was not merely a minor error that could be rectified through a "correction registration" (更正登記 - kōsei tōki) to validate it retroactively for the purpose of asserting leasehold rights under the Act. [cite: 1] The act of registering in B's name was a deliberate choice by Y. - Distinction from Prior Precedents:

The Court also addressed a precedent cited from the former Supreme Court (大審院 - Daishin'in), dated July 11, 1940. That earlier case had allowed an heir who had not yet completed inheritance registration for a building to nonetheless assert rights under the Building Protection Act. The current Court distinguished this, noting that the 1940 case involved a building that was initially validly registered in the name of the ancestor (the decedent). The issue there was a delay in updating the registration due to inheritance under the old family headship system (家督相続 - katoku sōzoku). In contrast, the present case involved a registration that was, from its inception, made in the name of someone other than the purported true owner-lessee (Y), by Y's own act. [cite: 1] Therefore, the earlier precedent was deemed inapplicable.

Based on this comprehensive reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that Y could not use the registration of Building O in his son B's name to assert his leasehold rights over Land K against X under the Building Protection Act. [cite: 1] Consequently, X's claim for the removal of the building and surrender of the land was upheld.

The Voices of Dissent: A Plea for Substantive Justice

While the majority took a formalistic approach centered on the integrity of the registration, several Justices issued dissenting opinions. Their arguments generally revolved around a more substantive interpretation of the Building Protection Act, emphasizing its socio-legal goals and the actual circumstances of the case.

The key arguments in the dissenting opinions included:

- Social-Protective Nature of the Act: The dissenters highlighted that the Building Protection Act was a piece of social legislation aimed at protecting the dwelling rights of lessees and their families who rely on buildings as their homes. They argued that its interpretation should be guided by this protective purpose, balancing it with the need to protect third parties in transactions.

- Actual Harm to Third Parties: A core point of contention was whether X, the new landowner, was genuinely misled or unfairly harmed. The dissenting Justices suggested that if the third party could have reasonably discovered the existence of Y's leasehold through on-site inspection and inquiry, then denying Y protection based solely on the name on the building registration might be too harsh. Given that B was Y's minor son, living with him in Building O, and bore the same family name, a diligent third party might have been alerted to Y's underlying rights. They argued that X could have easily inferred that B or his family (which included Y) had a leasehold right.

- Substance over Form: Some dissenters felt that the registration in B's name was, in substance, a registration for Y, especially given Y's motivations (illness and desire to simplify future affairs for his family). They argued that to deem such a registration completely ineffective under the Building Protection Act was an overly conceptual interpretation that ignored the practical realities of family life and property management. They posited that the registration was not "false" in a malicious sense and should be seen as Y acting for himself, merely using his son's name.

- Balancing Interests: The dissenters advocated for a balancing of the lessee's need for housing security against the third party's interest in transactional safety. They believed that in cases like this, where the family relationship was close and the living situation was apparent, the scale should tip more towards protecting the lessee, provided the third party was not unduly prejudiced.

Despite these compelling arguments from the minority, the majority view prevailed, setting a strict standard for the application of the Building Protection Act.

Significance and Broader Implications of the Ruling

This 1966 Grand Bench decision was a landmark for several reasons and continues to be a subject of legal discussion.

A Pivotal Grand Bench Decision

The judgment was significant not only for its direct impact on the parties but also as a pronouncement from the Supreme Court's highest deliberative body, the Grand Bench, especially given the presence of multiple dissenting opinions. [cite: 1] It firmly established that, under the Building Protection Act, registering a building in a nominee's name, even a close family member, was insufficient to perfect the land leasehold rights against a new landowner. [cite: 1] This ruling brought clarity, albeit a strict one, to the requirements for lessee protection under the Act and sparked considerable debate about the methods of public notification for land use rights. [cite: 1]

Navigating Two Lines of Precedent

Legal analysis of this period reveals two general trends in judicial decisions concerning defects in building registrations and their effect on leasehold perfection:

- Cases involving physical discrepancies: In instances where the registered information about the building (e.g., its structure, floor area, or even a slight error in the lot number) did not perfectly match the actual building, courts often upheld the lessee's ability to assert their leasehold rights. [cite: 1] This line of cases tended to prioritize the protection of the lessee if the building was identifiable and the third party was not seriously misled. [cite: 1]

- Cases involving nominee registration (discrepancy in owner's identity): This 1966 decision became a leading case for the second line, which took a stricter stance. It affirmed that if the building was registered in the name of someone other than the actual lessee, the lessee could not perfect their leasehold rights. [cite: 1] This followed an earlier, similar ruling by the Daishin'in in 1941. [cite: 1] The 1966 judgment pushed back against some post-war lower court decisions that had shown more leniency, for example, by recognizing perfection even when a building was registered in the name of the lessee's mother or child. [cite: 1, 2] The principles of this Grand Bench ruling were subsequently applied in cases involving buildings registered in a spouse's name as well. [cite: 2]

Academic Discourse and Critiques

The decision has been extensively debated by legal scholars, with differing views on its appropriateness:

- The Majority Academic View: Prioritizing Lessee Protection: Many academics criticized the judgment, arguing that it placed too much emphasis on the formal accuracy of the registration at the expense of the Building Protection Act's primary goal: safeguarding lessees. [cite: 2] They contended that the two lines of precedent mentioned above were inconsistent. [cite: 2] A common argument was that the type of "registration" required by the Building Protection Act was functionally different from the registration required for general property rights under Article 177 of the Civil Code. [cite: 2] The latter aims to publicly display the owner of the right, while the former, they argued, was primarily to signal the existence of a leasehold burdening the land. [cite: 2] From this perspective, if a third party, through on-site inspection, could reasonably infer that the land was subject to a lease (regardless of whose name the building was precisely in, as long as it indicated occupation), then the lessee should be protected. [cite: 2] The identity of the specific lessee was seen as less critical than the fact of the lease itself. [cite: 2]

- The Minority Academic View: Upholding Registration Formalities: Conversely, a minority of scholars supported the Supreme Court's decision. [cite: 2] They viewed the precedent lines as consistent when viewed through the lens of the overall validity of the registration itself. [cite: 2] They argued for a unified understanding of what constitutes a valid registration, believing that differentiating its effect for building ownership versus leasehold perfection would create unnecessary legal confusion. [cite: 2] This view often underscored the importance of maintaining the clarity and reliability of the registration system and aligned with the principle of individualism that underpins much of Japanese civil law. [cite: 2]

Alternative Paths to Lessee Protection (If Perfection Fails)

Even if a lessee fails to perfect their leasehold rights due to issues like nominee registration, Japanese law sometimes offers alternative, albeit more limited, avenues for protection:

- The Doctrine of Abuse of Rights (権利濫用 - kenri ranyō): In certain circumstances, even if a new landowner has a legal right to demand eviction (because the lessee's rights are not perfected against them), a court might find that the landowner's demand constitutes an "abuse of rights." [cite: 2] If such a finding is made, the eviction claim could be denied. [cite: 2] However, this doctrine provides a shield, not a sword; it doesn't grant the lessee a valid, assertable leasehold against the new owner. [cite: 2] The lessee's occupation might still be technically "unlawful," and this protection might not extend against a subsequent purchaser of the land. [cite: 2]

- The "Bad Faith Acquirer" Argument (背信的悪意者 - haishinteki akuisha): Some lower court judgments have developed a theory around "bad faith acquirers." This theory posits that a new landowner who acquires the land with knowledge of the lease and in a manner deemed particularly "treacherous" or "in bad faith" (going beyond mere knowledge of the lease) might be excluded from the definition of a "third party" who is entitled to claim lack of perfection. [cite: 2, 3] If the new owner is deemed a "bad faith acquirer," the lessee might be able to assert their leasehold rights even with a defective (or absent) building registration. [cite: 3] This approach, supported by many academics, focuses heavily on the subjective state of the new landowner. [cite: 3] However, the precise scope of relief under this theory and its consistent application remain complex, and it may not always fully address the substantive realities of every dispute. [cite: 3]

Enduring Relevance: The Judgment and the Act on Leased Land and Leased Houses

The Building Protection Act under which this 1966 case was decided has since been replaced by the Act on Leased Land and Leased Houses (借地借家法 - Shakuchi Shakka Hō, hereinafter ALLHL), enacted in 1991. Article 10, Paragraph 1 of the ALLHL largely mirrors the content of Article 1 of the old Building Protection Act. [cite: 3] According to some involved in drafting the ALLHL, this provision was intended to carry forward the substance of the older Act's rule. [cite: 3] If this understanding is strictly followed, the principles from the 1966 Grand Bench judgment could still be highly relevant to interpreting ALLHL Article 10(1). [cite: 3]

However, the ALLHL also introduced a new provision, Article 10, Paragraph 2, which deals with situations where a building is destroyed and the lessee posts a notice on the land. Some legal scholars argue that the introduction of Paragraph 2, and other nuances in the ALLHL, may signal a qualitative shift, perhaps imbuing the new Act with a greater emphasis on the actual, on-site conditions ("現地主義加味" - genchi shugi kami) when determining leasehold rights. [cite: 3] Such a shift could potentially limit the direct, unqualified application of the 1966 judgment to cases under the new Act. [cite: 3]

Interestingly, it has been observed that court decisions interpreting ALLHL Article 10(1) do not always explicitly cite or rely on precedents established under the old Building Protection Act, such as this 1966 case. [cite: 3] The precise current scope and influence of this historical judgment therefore depend on ongoing judicial interpretation and academic clarification of the purposes behind ALLHL Article 10(1). [cite: 3]

Furthermore, legal reforms in 2017 to the Japanese Civil Code have integrated provisions like ALLHL Article 10 with rules concerning the transfer of a lessor's status (e.g., Civil Code Article 605-2, Paragraph 1), adding another layer to the discussion about the requirements for asserting leasehold rights against new property owners. [cite: 3]

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1966 Grand Bench decision in the case of building registration under a nominee's name remains a critical reference point in Japanese property law. It underscores a fundamental principle: for a lessee to securely protect their leasehold rights against third parties through the registration of a building on the leased land, that registration must accurately reflect the lessee as the owner. While the socio-protective aims of tenancy laws are significant, this case demonstrates the high value the Japanese legal system places on the clarity, accuracy, and reliability of its public registration system as a cornerstone of secure property transactions. The ongoing evolution of legislation and jurisprudence continues to shape the precise contours of these principles, but the 1966 judgment serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of meticulousness in property dealings.