Japanese Supreme Court Clarifies Executor's Role in "Causing to Inherit" Wills and Complex Inheritance Disputes

Decision Date: December 16, 1999

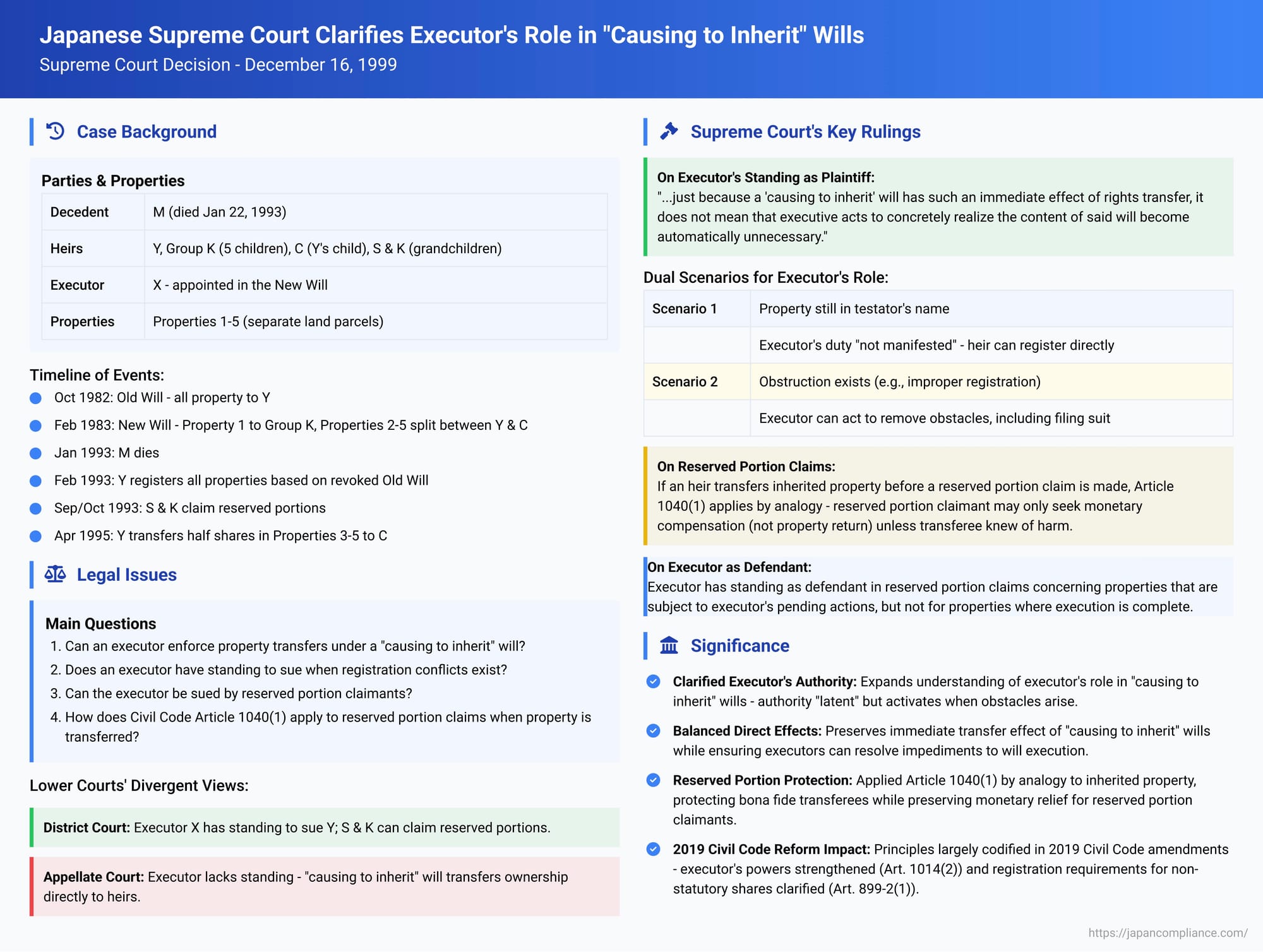

This article delves into a significant Japanese Supreme Court decision delivered on December 16, 1999. The case, primarily concerning the transfer of real property ownership, provides crucial clarifications on the duties and standing of an executor appointed under a will that "causes to inherit" specific assets to designated heirs. It also navigates complex issues involving conflicting wills, improper property registrations, and claims related to the legally reserved portion of an estate.

I. Outline of the Case

A. The Parties and the Estate

The case revolves around the estate of M, who owned several parcels of land (collectively "The Properties," individually "Property 1," "Property 2," etc.). M passed away on January 22, 1993, triggering the commencement of inheritance.

The heirs involved were:

- Six biological children of M: This group included Y (a key defendant in the subsequent litigation) and five other siblings (referred to collectively as "Group K").

- C: Y's child, who was also an adopted child of M.

- S and K: M's grandchildren, children of M’s predeceased eldest son (DS). S and K were heirs by representation, entitled to DS's share.

B. The Wills

M had executed two formal wills:

- The Old Will (October 15, 1982): This will stipulated that all of M’s property was to be inherited by her son, Y.

- The New Will (February 15, 1983): This later will expressly revoked the Old Will and laid out a new distribution plan:

- Property 1 was to be inherited by the five children in Group K, each receiving a one-fifth share.

- Properties 2 through 5 were to be inherited by Y and C, each receiving a one-half share.

- All other property owned by M was to be inherited equally by all legal heirs.

- X was designated as the executor of this New Will.

C. Post-Death Actions and Disputes

Despite the New Will, on February 5, 1993 (shortly after M's death), Y used the (revoked) Old Will to register all of The Properties into his own name, citing inheritance as the cause.

Later, on April 6, 1995, while the initial lawsuit was pending at the first instance court, Y transferred a one-half share in each of Properties 3, 4, and 5 to C. This transfer was registered as a "restoration of true registered title."

On September 29, 1993, S and K (the grandchildren) formally notified the other heirs and the executor X of their intention to claim their legally reserved portion (遺留分, iryūbun) of the estate. This notice was received by the respective parties between September 30 and October 8, 1993.

D. The Lawsuits

- Executor X's Claim: X, in his capacity as the executor of the New Will, sued Y. X demanded that Y undertake the registration procedures to restore the true ownership according to the New Will. Specifically:

- For Property 1: Transfer registration to the members of Group K.

- For a one-half share of Property 2: Transfer registration to C.

Y contested X's standing to sue (原告適格, genkoku tekikaku), arguing that in cases of a will "causing to inherit" specific property to particular heirs, there is no room for an executor to act regarding the property transfer. Y also claimed that Group K members had, on January 23, 1993, waived or assigned their inheritance shares in Property 1 to Y, thereby losing their rights to it.

- Intervenors S and K's Claims: S and K, having asserted their reserved portion rights, joined the ongoing lawsuit as independent parties. They claimed a 1/32nd share each in The Properties based on their reserved portion.

- Against X (the executor): They sought confirmation of their co-ownership share.

- Against Y: They sought confirmation of their co-ownership share and registration of this share transfer due to their reserved portion claim.

Y argued that S and K's exercise of their reserved portion rights was an abuse of rights. Y also asserted his own financial contributions (寄与分, kiyobun) to M's estate should be considered. Furthermore, Y contended that because Group K members had (allegedly) transferred their shares in Property 1 to him before S and K exercised their reserved portion rights, S and K could not claim the return of those property shares from him, citing Article 1040(1) of the Civil Code.

- S and K's Separate Lawsuit Against C: S and K also filed a separate lawsuit (later consolidated) against C, seeking confirmation of their co-ownership share in Properties 3, 4, and 5 based on their reserved portion claim, and the corresponding registration of share transfer. C argued that the claim was an abuse of rights.

E. Lower Court Rulings

- First Instance Court: This court largely found in favor of X and S & K.

- Appellate Court (Original Instance): The appellate court took a different view on the executor's role.

- It dismissed X's suit against Y, finding that X lacked standing as plaintiff.

- It also dismissed S and K's suit against X, finding X lacked standing as defendant.

- The reasoning was that a will "causing to inherit" specific property directly transfers ownership to the heir upon the testator's death. The heir can register the title themselves. Even if a conflicting registration exists, the heir can sue to cancel it based on their ownership. Thus, the appellate court concluded there was no scope for the executor to act in transferring or registering such property.

- However, the appellate court upheld S and K's claims against Y and C for their reserved portions.

X (the executor) appealed the dismissal of his claim to the Supreme Court (Appeal No. 1499). Y and C appealed the decision upholding S and K's reserved portion claims (Appeal No. 1500).

II. The Supreme Court's Judgment: Executor's Standing (Appeal No. 1499)

The Supreme Court addressed whether X, as the executor of M’s New Will, had the standing to sue Y to effectuate the property transfers stipulated in the New Will. The Court disagreed with the appellate court's conclusion and found that X did have standing.

A. Nature of a "Causing to Inherit" Will

The Court began by affirming a generally accepted principle (citing a previous Supreme Court case from April 19, 1991): A will that directs specific real property to be inherited by a specific heir (甲, "Heir A") is, in the absence of special circumstances, a designation of the method of estate division. Such a provision causes the property to be immediately succeeded to by Heir A through inheritance at the time of the testator's death, without requiring any further action.

B. Executor's Role Not Necessarily Eliminated

Crucially, the Supreme Court stated: "However, just because a 'causing to inherit' will has such an immediate effect of rights transfer, it does not mean that executive acts to concretely realize the content of said will become automatically unnecessary."

C. The Importance of Registration and Executor's Duties

The Court emphasized the significance of registration in real estate transactions. It reasoned that ensuring Heir A obtains the ownership transfer registration for the specified property falls under "acts necessary for the execution of the will" as stipulated in Article 1012(1) of the Civil Code. Therefore, facilitating such registration is within the scope of the executor's duties and authority.

The Court then distinguished two scenarios:

- Property Still in Testator's Name: If the property is still registered in the testator's name, established registration practice (under Article 27 of the Real Property Registration Act, now Article 63(2)) allows Heir A to unilaterally apply for the ownership transfer registration. In such a situation, the executor's duties are "not manifested" (職務は顕在化せず, shokumu wa ken-zai-ka sezu). The executor has neither the right nor the obligation to undertake the registration procedures (citing a Supreme Court case from January 24, 1995).

- Obstruction to Will's Execution: However, the present case was different. Before Heir A (or, here, Group K for Property 1, and C for part of Property 2) could be registered as owners according to the New Will, another heir (Y) had registered the properties in his own name based on the Old Will. This created a situation where the realization of the New Will was obstructed.

In such obstructive situations, the Supreme Court held:

- The executor, as part of executing the will, can demand the cancellation of the obstructing registration.

- Furthermore, the executor can demand the registration procedures for the "restoration of true registered title" in favor of the heirs designated by the will.

- The fact that Heir A themselves can also sue based on their ownership rights to achieve the same outcome does not affect or diminish the executor's authority to do so.

D. Conclusion on Executor X's Standing

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that X, as the executor of the New Will, did possess the standing (plaintiff's qualification) to sue Y. The appellate court's decision to the contrary was based on an erroneous interpretation and application of the law, and this error clearly affected the judgment. This part of the appellate judgment was overturned.

III. The Supreme Court's Judgment: Reserved Portion Claims (Appeal No. 1500)

The Supreme Court then turned to the appeal by Y and C concerning the reserved portion claims made by S and K. S and K each held a 1/32nd reserved portion in M's estate.

A. Arguments of Abuse of Right and Contributory Portion

The appellate court had rejected Y's arguments that S and K's claim was an abuse of rights and that Y's financial contributions (寄与分, kiyobun) should reduce the estate subject to the reserved portion claim.

The Supreme Court upheld the appellate court's findings on these two points:

- Abuse of Right: While DS (S and K's father) had received substantial gifts from DH (M's husband) and had waived inheritance from DH, there was no evidence that DS or S and K had agreed to waive inheritance from M or to not claim their reserved portion from M's estate. The Court found no grounds to deem the exercise of the reserved portion right as an abuse.

- Contributory Portion (Kiyobun): The Court affirmed that a contributory portion is determined by agreement among co-heirs or, failing that, by a family court determination. It cannot be raised as a defense in a lawsuit concerning a reserved portion claim.

The Supreme Court found no error in the appellate court's reasoning or its assessment of evidence on these points. Thus, C's appeal (which likely only involved these types of arguments) was dismissed as unfounded.

B. Transfer of Property Subject to Reserved Portion Claim (Civil Code Art. 1040(1))

This was a more complex issue, specifically concerning Property 1. Y had argued that members of Group K (the designated heirs of Property 1 under the New Will) had transferred their shares in Property 1 to him before S and K made their reserved portion claim. Y invoked Article 1040(1) of the Civil Code.

Article 1040(1) (at the time) stated: "If a person who is to have a gift abated [due to a reserved portion claim] has transferred the object of the gift to another person, the person entitled to the reserved portion may only claim monetary compensation from the donee for the value of the object, unless the transferee, at the time of the transfer, knew that it would prejudice the person entitled to the reserved portion."

The Supreme Court reasoned as follows:

- If a will "causes to inherit" specific property to Heir A (who is subject to a reserved portion claim), and Heir A transfers that inherited property to another person before the reserved portion claimant exercises their right, Article 1040(1) applies by analogy.

- In such a case, the reserved portion claimant can only demand monetary compensation from Heir A, and cannot demand the return of the property (or a share of it) from the transferee, unless the transferee knew at the time of the transfer that it would harm the reserved portion claimant.

- The "other person" (transferee) in this context can include a co-heir of Heir A.

Applying this to the facts: If members of Group K had indeed transferred their shares in Property 1 to Y before S and K made their reserved portion claim, then S and K could (unless Y knew the transfer would harm S & K) only seek monetary compensation from Group K members, not the return of the property shares from Y for Property 1.

The appellate court had interpreted Y's argument as merely a claim of waiver or assignment of inheritance rights in general by Group K members, and concluded this didn't fall under "transferring the object" in Article 1040(1). However, the Supreme Court noted that the record showed Y also specifically argued that Group K members had transferred their co-ownership shares in Property 1 to him.

Therefore, the Supreme Court found the appellate court erred. The appellate court should have made factual findings on whether such a transfer of property shares from Group K to Y occurred and then determined the applicability of Article 1040(1). This failure was an error in legal interpretation or a failure to adjudicate a pleaded issue, and it clearly affected the judgment. This part of Y's appeal was found to have merit.

The Court also added a note (付言, fugen) that even if S and K's claim for share transfer registration against Y concerning Property 1 was valid, the legal cause for registration for Property 1 (and also for Property 2 shares) would require further examination by the appellate court.

IV. The Supreme Court's Judgment: Executor's Standing as Defendant (Ex Officio)

The Supreme Court also addressed, on its own motion (職権により, shokken ni yori), the appellate court's dismissal of S and K's claim for confirmation of co-ownership against X (the executor) due to X's alleged lack of defendant standing.

A. Interrelation of Claims

S and K held a 1/32nd reserved portion each. Executor X was suing Y to register Property 1 to Group K and a half-share of Property 2 to C, which the Supreme Court had already deemed a valid act of will execution.

The Supreme Court reasoned that the success or failure of X's claims (to enforce the New Will's distribution) and the success or failure of S and K's reserved portion claims against those same properties were intrinsically linked ("two sides of the same coin" - 表裏の関係, hyōri no kankei). A unified and consistent resolution (合一確定, gōitsu kakutei) was necessary for these claims.

B. Executor's Defendant Standing for Properties 1 and 2

Given this interrelation, for the lawsuit concerning confirmation of S and K's co-ownership shares in Property 1 and Property 2 based on their reserved portion claims, the executor X did have standing as a defendant (被告適格, hikoku tekikaku).

C. No Defendant Standing for Properties 3-5

However, the situation was different for Properties 3, 4, and 5. For these properties, ownership transfer registrations consistent with the New Will (half to Y, half to C) had already been made (albeit initiated by Y claiming "restoration of true registered title" for C's share). The execution of the will regarding these specific properties was no longer a prospective issue requiring X's action. Therefore, X did not have defendant standing for S and K's confirmation claims related to Properties 3, 4, and 5.

The appellate court's decision dismissing S and K's claim against X concerning Properties 1 and 2 was thus found to be based on an erroneous interpretation of law, affecting the judgment.

V. Conclusion of the Supreme Court

Based on the foregoing reasons, the Supreme Court issued the following judgment:

- Partial Overturn and Remand: The appellate court's judgment was overturned except for the part concerning S and K's claims against Y and C for confirmation of co-ownership and share transfer registration for Properties 3, 4, and 5 (which the appellate court had granted and the Supreme Court did not disturb for C, and would later be affected by the Art. 1040(1) issue for Y). The overturned portions were remanded to the Tokyo High Court for further trial and adjudication.

- Dismissal of Y's Appeal (in part): Y's appeal concerning Properties 3, 4, and 5 (where his liability to S&K was upheld by the appellate court regarding the reserved portion, subject to the Art. 1040(1) point for Property 3,4,5 if any part was deemed transferred from other beneficiaries) was dismissed.

- Dismissal of C's Appeal: C's entire appeal was dismissed (as his arguments about abuse of right were rejected).

- Costs: Costs were allocated accordingly.

The Court noted that although Y's appeal regarding Property 2 was unfounded on its primary grounds (abuse of right, etc.), because the litigation concerning Properties 1 and 2 required a unified resolution among X, Y, and S & K, a separate dismissal of Y's appeal for Property 2 was not explicitly stated in the main operative part of the judgment that dealt with dismissals.

VI. Analysis and Significance of the Decision

This 1999 Supreme Court judgment offers profound insights into the administration of estates in Japan, particularly concerning the powers of an executor when a will "causes to inherit" specific assets.

A. Clarifying the Executor's Role in "Causing to Inherit" Wills

The most significant aspect of this decision is its clarification that even though a "causing to inherit" provision in a will can lead to an immediate transfer of property rights to the designated heir upon the testator's death, this does not render the executor powerless or their role redundant.

- Reconciling Previous Rulings: The Court skillfully navigated prior case law. Some earlier decisions (e.g., Supreme Court, Jan 24, 1995) had suggested that if an heir could independently register the inherited property, the executor had no duty or right to do so. Another case (Supreme Court, Feb 27, 1998) indicated that, absent specific instructions in the will, an executor might not have duties to manage or deliver such specifically bequeathed property. This 1999 decision does not directly overturn these but contextualizes them. It posits that the executor's underlying authority, derived from the Civil Code (Art. 1012(1) – "necessary acts for execution"), remains. This authority becomes "manifested" and actionable when obstacles arise that prevent the straightforward realization of the will's terms.

- Distinction between Latent Duty and Active Intervention: The Court drew a practical line: if the path is clear for the heir to obtain registration, the executor's role remains latent. However, if, as in this case, another party's actions (Y registering the property under a revoked will) obstruct the intended inheritance, the executor's duty to take "necessary acts" crystallizes. These acts can include suing to nullify improper registrations and to establish the correct title as per the will. The executor acts to ensure the will's provisions are "concretely realized."

- Separation of Substantive Civil Code Duties and Procedural Registration Practices: The judgment implicitly separates the executor's fundamental duties under the Civil Code (to execute the will) from the specific procedures and practices of the Real Property Registration Act. While registration law might allow an heir to act alone in simple cases, this doesn't strip the executor of their broader Civil Code mandate to overcome impediments to the will's execution.

B. Navigating Reserved Portion Claims Amidst Conflicting Transfers

The Court's application of Article 1040(1) of the Civil Code by analogy to inherited property (not just gifts) that is subsequently transferred before a reserved portion claim is made is also noteworthy. This highlights the protections afforded to bona fide transferees and channels reserved portion claims towards monetary compensation from the heir who made the transfer, rather than recovery of the specific asset from the transferee, unless the transferee acted in bad faith. The remand on this point emphasized the need for careful factual determination of the timing and nature of alleged intra-heir transfers.

C. Implications for Estate Practice

This decision provides executors with greater certainty about their authority to act decisively when the execution of a "causing to inherit" will is challenged or obstructed. It confirms that their role is not merely passive in such scenarios.

For heirs, it underscores the direct nature of "causing to inherit" bequests but also highlights that an executor can step in to protect the integrity of the will's execution.

The discussions around reserved portions and the impact of prior property transfers remain complex, requiring careful attention to the facts of each transfer and the knowledge of the parties involved.

D. Subsequent Legal Developments

It is worth noting that while this 1999 judgment left open the question of whether registration is required for an heir to assert rights (obtained via a "causing to inherit" will) against third parties (対抗要件, taikō yōken), this issue was addressed by a later Supreme Court decision (June 10, 2002), which held that registration was not necessary to assert such rights against third parties.

However, significant amendments to the Japanese Civil Code in 2018 (effective 2019) have since changed the landscape regarding this point. The revised Civil Code (Art. 899-2(1)) now stipulates that for inherited shares exceeding the statutory inheritance share, registration (or other perfection requirements) is necessary to assert rights against third parties. Furthermore, the 2018 reforms also clarified and strengthened the executor's powers, including the authority to take actions necessary to perfect the rights of heirs (Civil Code Art. 1014(2)), effectively aligning with and expanding upon the proactive role for executors supported by this 1999 judgment.

In conclusion, the Supreme Court's December 16, 1999, decision remains a landmark ruling. It adeptly balanced the principle of direct inheritance under "causing to inherit" wills with the practical necessity of an executor's intervention when the testator's intentions are threatened by subsequent events, thereby ensuring that the executor can indeed perform the "necessary acts" to give full effect to the will.