Japanese Supreme Court Affirms Constitutionality of Corporate Reorganization Law in Landmark 1970 Decision

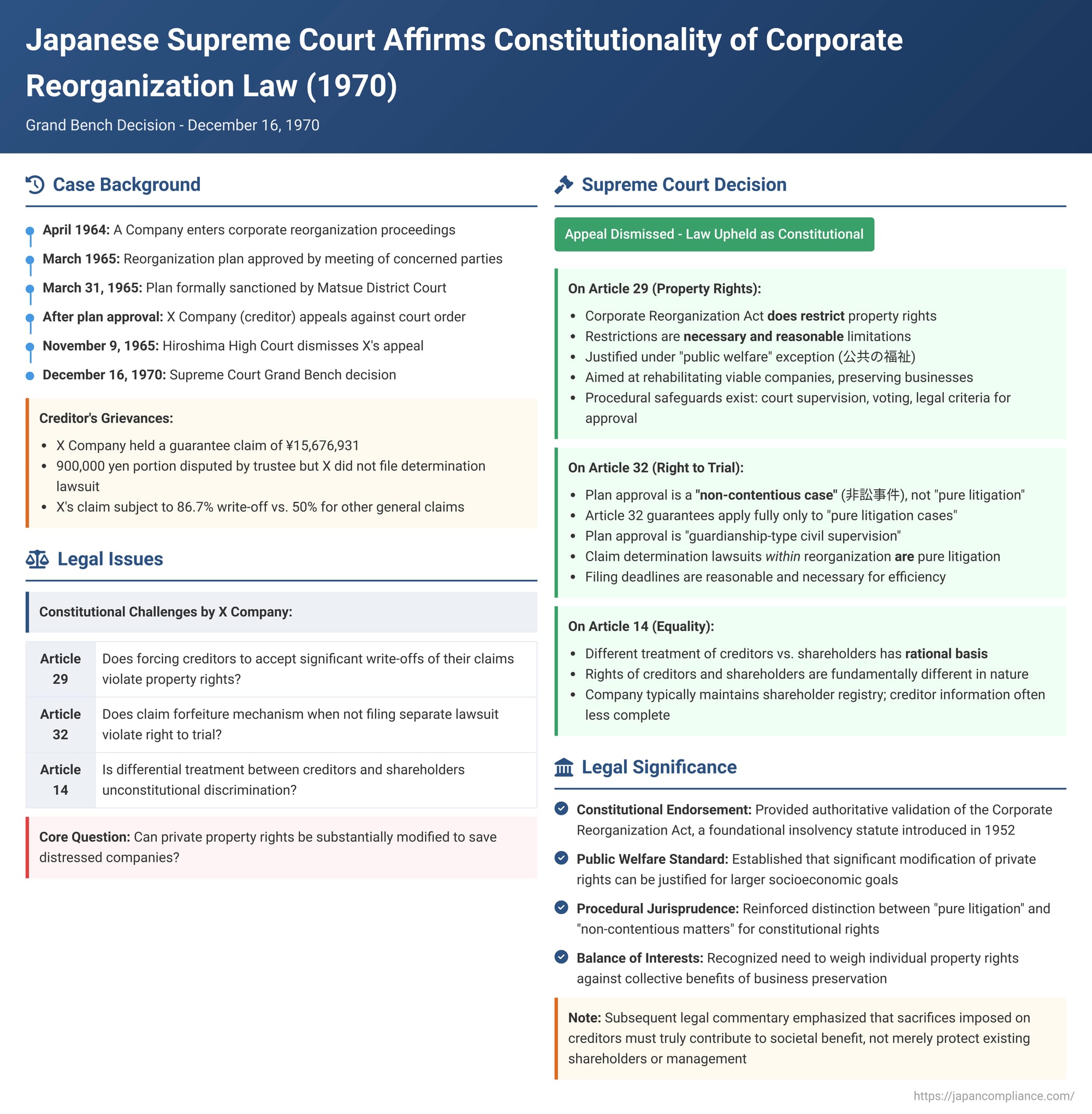

On December 16, 1970, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a seminal judgment affirming the constitutionality of key provisions of the (then) Corporate Reorganization Act. The case addressed fundamental challenges based on property rights (Article 29 of the Constitution), the right to a trial (Article 32), and the principle of equality (Article 14). This decision solidified the legal foundation for corporate rehabilitation in Japan, balancing the interests of distressed companies, their creditors, and the broader public welfare.

Background of the Corporate Reorganization and Appeal

The case involved A Company, which entered corporate reorganization proceedings in April 1964. A reorganization plan for A Company was subsequently approved at a meeting of concerned parties in March 1965 and formally sanctioned by the Matsue District Court on March 31, 1965.

X Company, a creditor of A Company, held a guarantee claim amounting to 15,676,931 yen. During the proceedings, A Company's reorganization trustee, B, raised objections to 900,000 yen of X Company's filed claim. X Company did not initiate a separate lawsuit to definitively establish the disputed portion of its claim. Consequently, its claim was confirmed only for the undisputed amount, effectively reducing it by the 900,000 yen to which objection had been made.

Furthermore, A Company's reorganization plan stipulated a significantly higher write-off (exemption rate) for X Company's claim—86.7%—compared to the 50% write-off applied to other general reorganization claims. Dissatisfied with both the reduction of its claim amount due to the unchallenged objection and the substantially higher write-off rate, X Company filed an immediate appeal against the court's order sanctioning the reorganization plan. X Company also broadly challenged the constitutionality of several provisions within the Corporate Reorganization Act itself.

The Hiroshima High Court, Matsue Branch, dismissed X Company's appeal on November 9, 1965. The High Court reasoned that the difference in write-off rates was justifiable because X Company's claim, being a guarantee claim, differed in nature from other commercial claims, thus satisfying substantive equality. The constitutional arguments were also rejected. This led X Company to file a special appeal with the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Appellant Creditor's Constitutional Challenges

In its special appeal, X Company presented three main constitutional arguments against the Corporate Reorganization Act and its application:

- Violation of Property Rights (Article 29): X Company contended that the Corporate Reorganization Act, by its very design of protecting a private enterprise (A Company) at the expense of its creditors (like X Company), fundamentally infringes upon the property rights guaranteed by Article 29 of the Constitution. The argument implied that forcing creditors to accept significant modifications to their claims to save a debtor company was an unconstitutional taking or infringement of property.

- Violation of Just Compensation and Right to a Trial (Articles 29(2) and 32): X Company argued that the statutory mechanism within the Corporate Reorganization Act, which led to the forfeiture (shikken) of the disputed 900,000 yen portion of its claim because it did not file a separate claim determination lawsuit, violated both Article 29(2) (requiring just compensation for property taken for public use) and Article 32 (guaranteeing the right to a trial). The inability to otherwise appeal the substantive terms of the approved plan was also implicated under the Article 32 challenge.

- Violation of Equality (Article 14): X Company asserted that the Corporate Reorganization Act created an unconstitutional discrimination contrary to Article 14 by imposing different procedural requirements on creditors and shareholders. Specifically, creditors were required to formally file their claims within a set period to participate in the proceedings and avoid forfeiture, whereas shareholders were often not subject to a similar stringent filing requirement for their existing shares to be considered or modified under the plan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision by its Grand Bench, dismissed X Company's special appeal, upholding the constitutionality of the Corporate Reorganization Act on all contested points.

1. Upholding Restrictions on Property Rights (Article 29)

The Court acknowledged that the Corporate Reorganization Act undeniably imposes restrictions on the property rights of creditors, shareholders, and other interested parties. Such restrictions include the stay on debt payments outside the reorganization process, the modification of terms (like maturity extensions or debt write-offs) through a reorganization plan, the discharge of debts, and the alteration or extinguishment of shareholder rights and security interests not recognized in an approved plan.

However, the Court contextualized these restrictions within the overarching purpose of the Act. It stated that the Act aims to rehabilitate financially distressed but viable corporations, thereby adjusting the interests of various stakeholders to preserve the company's business. This objective is pursued because the collapse and liquidation of such enterprises can lead not only to losses for directly involved parties but also to broader social and national economic detriments.

The Court found these restrictions on property rights to be necessary and unavoidable measures to achieve the Act's legitimate objectives. Crucially, it emphasized the procedural safeguards embedded within the Act to ensure fairness and equity. These include:

- The entire reorganization process being conducted under the supervision of the court.

- Adherence to strict, legally prescribed procedures.

- The reorganization plan itself being subject to deliberation and voting at a meeting of concerned parties (including creditors) according to detailed rules.

- The plan requiring court sanction (approval) to become effective, with the Act specifying the necessary conditions for such approval.

Given these "thorough and rational provisions" designed for fair and equitable achievement of the Act's goals, the Supreme Court concluded that the restrictions on property rights were necessary and reasonable limitations permissible under the Constitution for the "public welfare" (kōkyō no fukushi). Therefore, the challenged provisions of the Corporate Reorganization Act did not violate Article 29, paragraphs 1 or 2, of the Constitution.

2. Addressing the Right to a Trial (Article 32) and Claim Forfeiture

Regarding X Company's argument that the claim forfeiture mechanism and limitations on appealing plan approvals violated Article 32 (right to a trial), the Court drew upon its established jurisprudence distinguishing between different types of judicial proceedings.

- "Pure Litigation" vs. "Non-Contentious Matters": The Court reiterated that "trial" as mentioned in Article 32 (and Article 82, on public trials) refers specifically to "pure litigation cases" (junzen taru soshō jiken). These are proceedings where a court definitively establishes facts and determines the existence of substantive rights and obligations between parties, as an exercise of inherent judicial power. Article 32, the Court stated, guarantees access to such litigation. Conversely, "non-contentious cases" (hishō jiken), which are not considered part of the inherent judicial power, do not fall under the purview of Article 32's guarantees.

- Plan Approval as Non-Contentious: The Court classified the judicial act of approving or disapproving a corporate reorganization plan as belonging to the state's "guardianship-type civil supervision" (kōkenteki minji kantoku). As such, it is essentially a non-contentious case, and appeals against such decisions are also not pure litigation.

- Claim Forfeiture as a Consequence: The forfeiture of claims (like the disputed portion of X Company's claim, or claims not recognized in an approved plan) is a legal effect that arises from a validly approved reorganization plan; it's a change in private rights mandated by law as a consequence of the plan.

- No Violation of Article 32: Therefore, the provisions related to claim forfeiture and the then-existing rules limiting appeals against plan approval decisions were deemed to be regulations concerning non-contentious matters. They did not constitute a restriction or deprivation of the right to a trial protected by Article 32.

The Court did acknowledge that a claim determination lawsuit filed within the reorganization proceedings (which X Company did not pursue for the disputed amount) is considered a pure litigation case. However, it found that the statutory deadlines for filing claims and for initiating such determination suits were necessary and reasonable for achieving the objectives of the Corporate Reorganization Act and did not effectively deny the right to a trial. The restrictions on property rights resulting from these claim filing and determination procedures were also considered justifiable under Article 29(2) for the public welfare.

3. Justifying Differential Treatment (Article 14 - Equality)

X Company argued that it was discriminatory under Article 14 for creditors to face forfeiture if they failed to file claims, while shareholders often did not need to formally file their existing shares to have them recognized or altered under a plan.

The Supreme Court first noted that Article 14(1) prohibits discrimination without rational grounds; it does not mandate absolute equality in all circumstances. Differential treatment is permissible if based on the nature of the matter and is reasonable.

The Court found the different treatment of creditors/secured creditors and shareholders in terms of claim/interest registration to be a rational distinction. The reasons provided were:

- The nature of the rights held by creditors (claims for debt) and shareholders (equity interests) are inherently different.

- From a practical standpoint, the company is generally aware of the number and details of its shares and the identity of its shareholders through its shareholder registry and other records. This is not always the case for all potential creditors and the specifics of their claims.

Therefore, the Court concluded that the differing procedural requirements for creditors and shareholders were justified by these intrinsic differences and did not constitute unconstitutional discrimination under Article 14(1).

Significance and Broader Implications of the Decision

This 1970 Supreme Court decision was pivotal. It provided a comprehensive constitutional endorsement of the Corporate Reorganization Act, which had been introduced in Japan in 1952, drawing inspiration from U.S. law. This affirmation was crucial for the Act's subsequent application and development, allowing it to become a vital tool for rescuing and rehabilitating distressed companies.

The judgment firmly established the "public welfare" argument as a powerful legal basis for justifying significant interferences with private property rights in the context of collective insolvency proceedings. This has had a lasting impact on how Japanese law balances the protection of individual creditor rights against broader socio-economic goals, such as preserving viable businesses and employment.

The Court's consistent reliance on the distinction between "pure litigation" and "non-contentious matters" to define the scope of the constitutional right to a trial (Article 32) was also reinforced. This distinction continues to shape procedural rights in various specialized legal fields beyond insolvency.

However, legal commentary following the decision, and in the years since, has also highlighted the importance of ensuring that the powers granted under the Corporate Reorganization Act are exercised fairly and truly serve the public good. There were concerns, particularly in the early years of the Act's application, that reorganizations could sometimes disproportionately benefit the debtor company and its existing management at the significant expense of creditors. As one commentary notes, the sacrifices imposed on creditors should ultimately contribute to societal benefit rather than merely preserving the interests of incumbent shareholders or managers. For the system to maintain legitimacy, it's crucial that its application ensures that the burdens of reorganization are equitably shared and that the "fresh start" provided to companies leads to genuine economic and social value. This might involve, for instance, careful scrutiny of business viability and ensuring that any value generated through creditor sacrifices is appropriately allocated.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's December 16, 1970, judgment was a landmark ruling that validated the core tenets of Japan's corporate reorganization framework against fundamental constitutional challenges. By deeming the Act's restrictions on property rights as permissible for the public welfare and by confining the full scope of the right to a trial to "pure litigation cases," the Court provided a robust legal foundation for a system designed to save rather than liquidate troubled but potentially viable enterprises. This decision has profoundly influenced the landscape of Japanese insolvency law and practice for decades, though the imperative remains to ensure that such powerful legal tools are always applied with fairness, transparency, and a clear view towards achieving genuine public benefit.