Japan, US, and EU Advertising Regulation: A Comparative Look at Japan's Keihyōhō

TL;DR

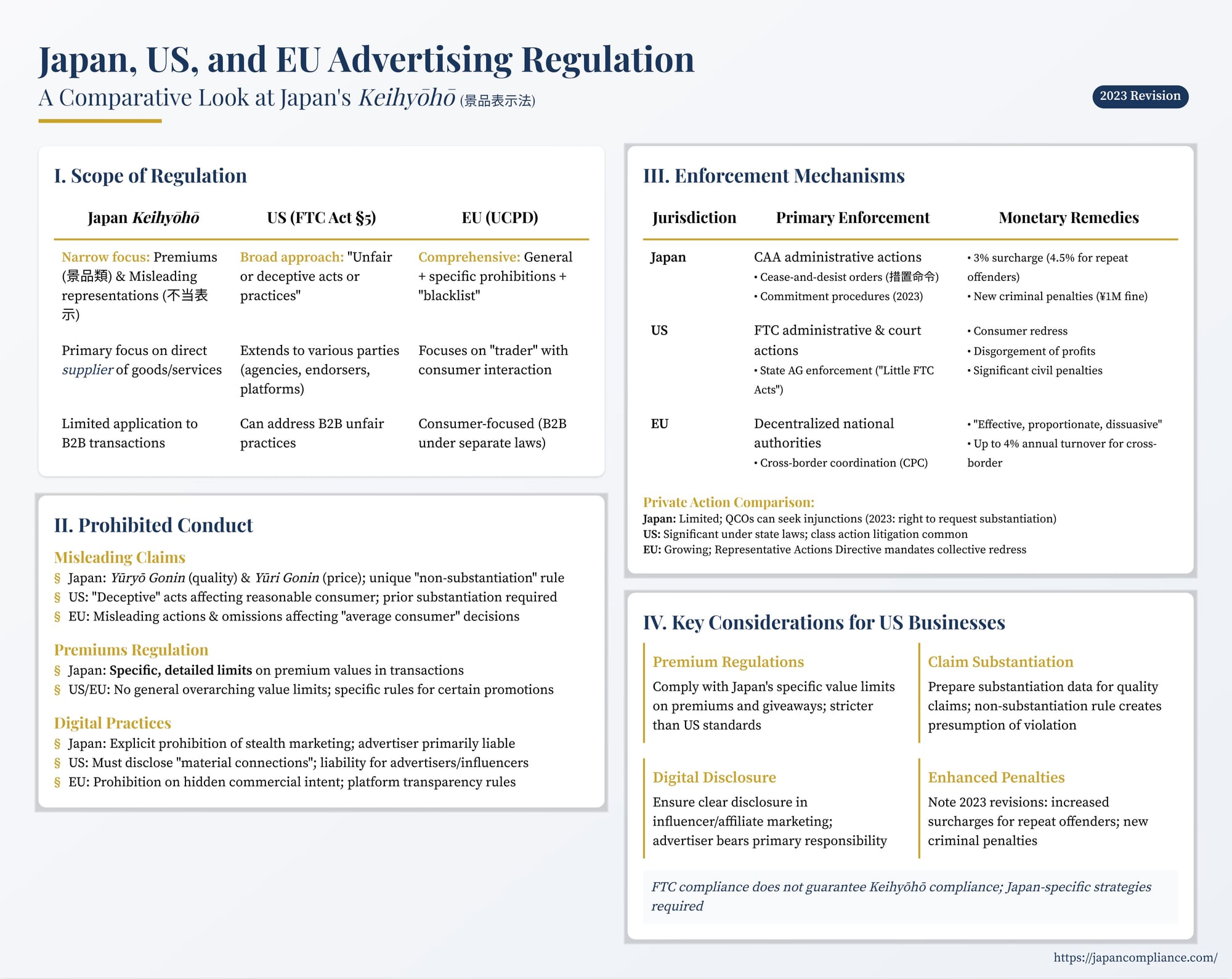

- Japan’s Keihyōhō, the FTC Act (§5) and the EU’s UCP Directive all ban deceptive advertising, yet diverge on enforcement: Japan relies on a 3 % (4.5 % repeat) turnover surcharge and a new commitment procedure; the FTC wields civil penalties and broad “unfairness” powers, while the EU uses a blacklist plus injunctive relief.

- Digital media receive no special exemption in Japan—advertisers remain strictly liable for affiliate and influencer content, and undisclosed stealth marketing is now expressly prohibited.

- Multinationals must localise substantiation files, premium-offer limits, and disclosure hashtags to avoid Consumer Affairs Agency (CAA) action.

Table of Contents

- Scope of Regulation: Who and What is Covered?

- Prohibited Conduct: Misleading Claims, Premiums, and Digital Practices

- Enforcement Mechanisms: Powers and Remedies

For multinational corporations, navigating the complex web of advertising regulations across different jurisdictions is a critical compliance challenge. While the goal of protecting consumers from deceptive practices is shared globally, the legal frameworks, enforcement priorities, and specific rules can vary significantly. Japan's primary tool in this arena is the Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations (景品表示法 - Keihin Hyōji Hō, or Keihyōhō).

Understanding how the Keihyōhō compares to its major counterparts in the United States (primarily Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act) and the European Union (the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive, UCPD) is essential for businesses, particularly those based in the US, looking to market effectively and compliantly in Japan. This article provides a comparative overview, highlighting key distinctions in scope, prohibited conduct, and enforcement, incorporating insights from recent analyses and the context of Japan's 2023 Keihyōhō revisions.

1. Scope of Regulation: Who and What is Covered?

A fundamental difference lies in the scope of activities and entities regulated by each regime.

- Japan (Keihyōhō): The Keihyōhō has a relatively specific focus. It primarily regulates two main areas:

- Premiums (景品類 - Keihinrui): Offers of gifts, prizes, or other economic benefits provided in connection with a transaction to induce customers. The Act allows the government to set limits on the value and type of premiums offered.

- Misleading Representations (不当表示 - Futō Hyōji): False or misleading statements about goods or services.

Furthermore, the provisions concerning misleading representations (Article 5) are largely limited to representations made by the "Entrepreneur...in connection with the transaction of goods or services which the Entrepreneur supplies." This "supplier limitation" means the law directly targets the business selling the product or service, making it more challenging to directly regulate third parties like advertising platforms or influencers under this core provision, unless they are deeply integrated into the supply or representation process itself.

- United States (FTC Act Section 5): Section 5 of the FTC Act adopts a much broader approach. It prohibits "unfair methods of competition" and "unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce." This covers a vast range of activities beyond just specific representations or premiums. Crucially, it is not limited to the direct "supplier" of goods or services; liability can extend to various parties involved in deceptive or unfair commercial practices, including advertising agencies, endorsers, and potentially platforms, depending on their involvement and knowledge.

- European Union (UCPD): The UCPD aims for comprehensive harmonization across EU Member States regarding "unfair commercial practices" that harm consumers' economic interests. It applies to any act, omission, course of conduct, representation, or commercial communication by a "trader" directly related to the promotion, sale, or supply of a product to consumers. It employs a multi-layered approach:

- A general clause prohibiting practices contrary to professional diligence that materially distort consumers' economic behavior.

- Specific prohibitions on misleading practices (actions and omissions) and aggressive practices.

- A "blacklist" of specific practices deemed unfair in all circumstances (e.g., certain types of bait advertising, false endorsements, pyramid schemes).

The UCPD's focus on "commercial practices" gives it a potentially broader scope than the Keihyōhō's focus on "representations" and "premiums," and its direct application focuses on the "trader" interacting with the consumer.

Key Comparison Points on Scope:

- Subject Matter: Japan's Keihyōhō is narrower, focusing on premiums and specific categories of misleading representations. The US and EU laws cover a wider range of "unfair" or "deceptive" practices beyond just advertising claims.

- Liable Parties: Japan's primary focus on the "supplier" contrasts with the potentially broader reach of US law to various market participants and the EU's focus on the "trader." While Japan is exploring ways to address third-party involvement (e.g., potential accomplice liability under new criminal provisions, advertiser responsibility for affiliates), the core statutory limitation remains significant.

- B2B Transactions: The Keihyōhō is primarily aimed at protecting general consumers, and its application to business-to-business transactions is limited. FTC Act Section 5 and EU rules (though UCPD is consumer-focused, other competition or contract laws apply) can more readily address unfair or deceptive practices in B2B contexts.

2. Prohibited Conduct: Misleading Claims, Premiums, and Digital Practices

While all three systems aim to prevent consumers from being misled, their approaches to specific types of conduct differ.

- Misleading Advertising Claims:

- Japan: Focuses on Yūryō Gonin (misleading quality/substance) and Yūri Gonin (misleading price/terms), plus designated categories like stealth marketing. Requires demonstrating claims are significantly misleading compared to reality or competitors. Japan also has a unique "non-substantiation" rule where failure to provide reasonable grounds for a quality/performance claim upon CAA request can lead to the claim being deemed misleading in administrative proceedings (though not in criminal ones).

- US: Prohibits "deceptive" acts or practices. A representation, omission, or practice is deceptive if it is likely to mislead a consumer acting reasonably under the circumstances and is "material" (likely to affect the consumer's conduct or decision). The FTC requires advertisers to have a "reasonable basis" for objective claims before disseminating them.

- EU: The UCPD prohibits misleading actions (false information or deceptive presentation) and misleading omissions (material information left out) that cause or are likely to cause the average consumer to take a transactional decision they wouldn't have otherwise taken. It includes specific rules against misleading price indications and comparative advertising.

- Premiums Regulation:

- Japan: Has specific, detailed regulations limiting the value of premiums offered in connection with transactions (both lottery-style and giveaways to all purchasers). This reflects a historical concern about excessive giveaways distorting fair competition and consumer choice.

- US/EU: While specific promotions might be subject to targeted rules (e.g., regarding gambling, sweepstakes disclosures), there isn't a general, overarching system limiting the value of premiums in the same way as Japan's Keihyōhō within the core consumer protection frameworks like the FTC Act or UCPD. Unfairness principles could potentially apply in extreme cases.

- Digital Advertising Practices (Influencers, Stealth Marketing):

- Japan: Recently explicitly prohibited stealth marketing (undisclosed advertising) via a designated notice under Article 5, Item 3. Guidelines emphasize advertiser responsibility for affiliate marketing content and require clear disclosure of commercial relationships in influencer marketing to avoid the stealth marketing prohibition. Liability still primarily rests with the advertiser.

- US: The FTC has long-standing guidelines on endorsements and testimonials, requiring clear and conspicuous disclosure of any "material connection" between an endorser (e.g., influencer) and the advertiser that might affect the weight or credibility consumers give the endorsement. Failure to disclose is considered deceptive. The FTC has pursued enforcement actions against advertisers and sometimes influencers or intermediaries.

- EU: The UCPD's prohibition on misleading omissions covers failure to identify commercial intent when it's not apparent from the context. Several blacklisted practices also relate to false endorsements or hidden advertising. The Digital Services Act further imposes transparency obligations on platforms regarding advertising. National authorities actively enforce disclosure rules for influencer marketing.

Key Comparison Points on Conduct:

- Japan's structured categories of misleading representations contrast with the broader US "deception" and EU "misleading practice" standards.

- Japan's specific regulation of premium values is unique compared to the general US/EU consumer protection laws.

- All three jurisdictions are actively tackling undisclosed digital advertising (stealth/influencer marketing), generally requiring clear disclosure of commercial intent, though the specific legal mechanisms differ. Japan's primary liability focus remains on the advertiser due to the Keihyōhō structure.

3. Enforcement Mechanisms: Powers and Remedies

The ways in which these laws are enforced also show significant variation.

- Japan (Keihyōhō):

- Primary Enforcement: Administrative actions by the CAA are central. This includes issuing cease-and-desist orders (措置命令) and imposing administrative surcharges (課徴金) of 3% (or 4.5% for repeat offenders) on relevant sales for superior/advantageous misrepresentations.

- New Tools (2023 Revision): Commitment procedures allow for negotiated settlements without formal orders. Direct criminal penalties (fines up to JPY 1 million) can now be sought for intentional superior/advantageous misrepresentations.

- Private Action: Limited direct private right of action for consumers under Keihyōhō itself. Qualified Consumer Organizations (QCOs) can seek injunctions against misleading representations and certain other violations. The 2023 revision allows QCOs to request substantiation data from businesses for quality claims.

- United States (FTC Act):

- Primary Enforcement: The FTC uses both administrative proceedings (leading to cease-and-desist orders) and federal court actions.

- Remedies: The FTC can seek court-ordered injunctions, consumer redress (monetary relief for consumers), disgorgement of ill-gotten gains, and civil penalties, particularly for violations of existing orders or specific rules. Civil penalties can be substantial.

- Other Actors: State Attorneys General actively enforce similar state laws ("Little FTC Acts"). Private rights of action are generally available under state laws, but not typically under the federal FTC Act itself for consumers.

- European Union (UCPD):

- Primary Enforcement: Decentralized enforcement by national authorities (consumer protection agencies, courts) within each Member State. Powers vary but generally include injunctions and fines. The Consumer Protection Cooperation (CPC) Regulation facilitates cross-border enforcement coordination.

- Penalties: The UCPD requires penalties to be "effective, proportionate and dissuasive." Recent EU directives (part of the "New Deal for Consumers") mandated that member states implement rules allowing for significant fines (e.g., up to at least 4% of annual turnover) for widespread cross-border infringements.

- Private Action: The UCPD requires Member States to ensure consumers harmed by unfair practices have access to effective remedies, including potentially damages. The EU Representative Actions Directive further mandates collective redress mechanisms across Member States.

Key Comparison Points on Enforcement:

- Primary Mechanism: Japan relies heavily on administrative orders and surcharges from the CAA. The US uses a mix of FTC administrative/court actions and state-level enforcement. The EU relies on decentralized national enforcement coordinated at the EU level.

- Monetary Penalties: The US FTC potentially wields the largest monetary power through civil penalties and consumer redress actions. EU Member States are now required to have potentially significant fining powers for widespread violations. Japan's administrative surcharges are formulaic (based on sales percentage) and criminal fines are currently modest, though the surcharge multiplier adds teeth.

- Consumer Redress: Consumer redress is a significant focus of FTC court actions. EU law increasingly mandates access to remedies for consumers. Japan's administrative system has limited direct consumer redress mechanisms (though voluntary refunds can reduce surcharges, and commitment plans may include redress).

- Private Litigation: Significant under US state laws and increasingly facilitated in the EU. More limited directly under Japan's Keihyōhō, though QCO injunctions play a role.

Conclusion: Navigating the Differences

While Japan, the US, and the EU share the common objective of protecting consumers from unfair and deceptive marketing, their legal frameworks diverge in important ways. Japan's Keihyōhō is characterized by its specific focus on premiums and defined categories of misleading representations, its primary application to the direct supplier of goods/services, and its historically administrative-centric enforcement model.

The 2023 revisions, however, signal a move towards strengthening enforcement in Japan, introducing commitment procedures for flexibility, significantly increasing surcharges for repeat offenses, and adding the potential for direct criminal liability for intentional core misrepresentations.

For US businesses operating in Japan, it is crucial not to assume that compliance with US FTC standards automatically ensures compliance with the Keihyōhō. Key areas requiring specific attention include Japan's detailed premium regulations, the nuances of substantiating claims to meet CAA expectations (especially under the non-substantiation rule for quality claims), the explicit prohibition and disclosure requirements related to stealth marketing, and understanding the advertiser's primary responsibility even for content generated by affiliates or influencers. Awareness of the strengthened penalty regime underscores the importance of prioritizing robust, Japan-specific compliance efforts.

- Key Changes in Japan's 2023 Premiums and Representations Act Revision

- Digital Deception or Fair Play? Applying Japan's Premiums and Representations Act to Online Advertising

- “Sutema” No More: Understanding Japan's Stealth-Marketing Regulations

- Consumer Affairs Agency – Comparative Study on Advertising Regulation (JP)

- METI – Cross-Border E-commerce Guidelines (JP)