Record ¥101 B Antitrust Surcharge: Inside Japan’s Electricity Cartel Crackdown

TL;DR

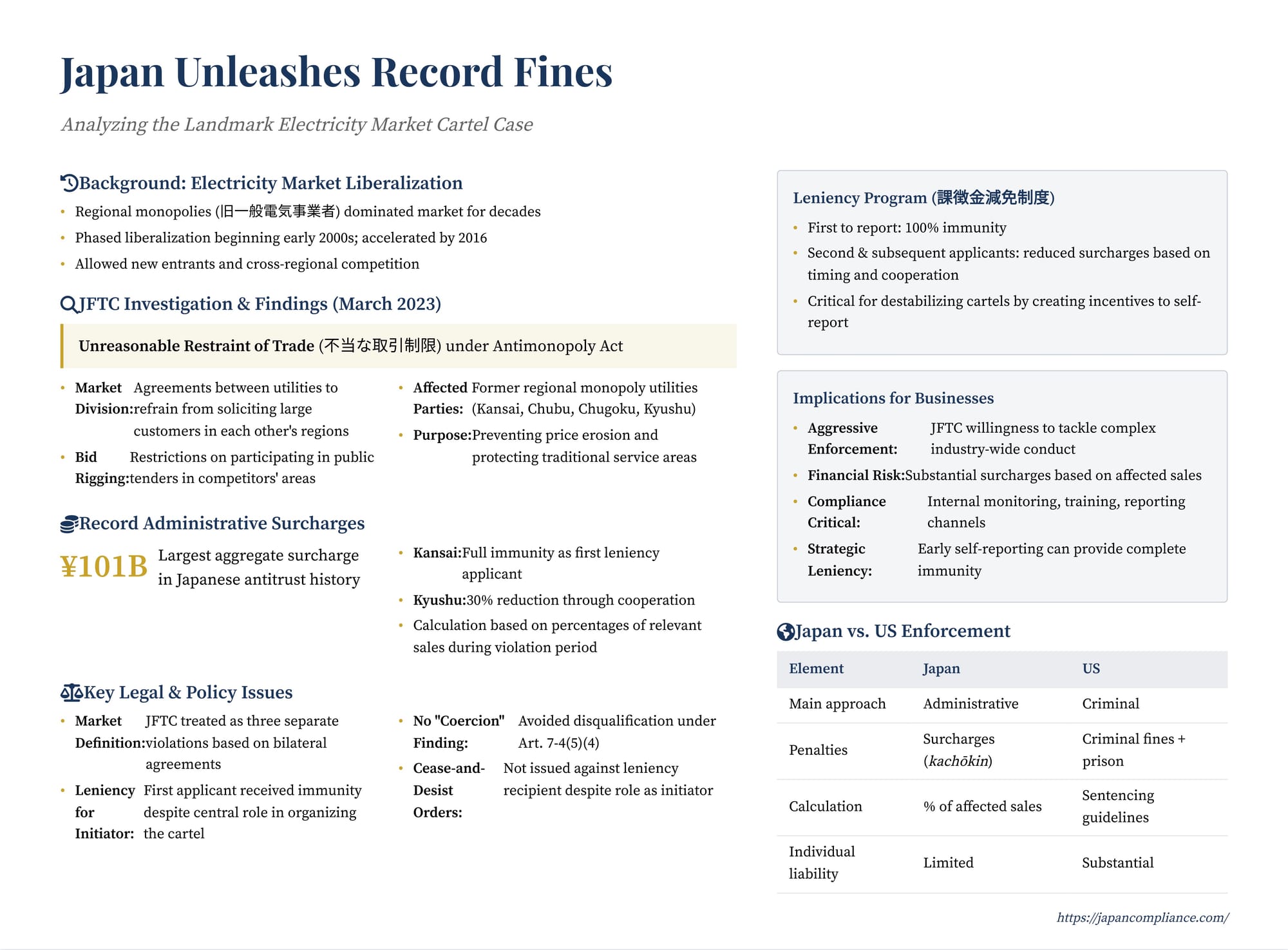

- ¥101 billion surcharge—largest in Japanese antitrust history—hit three regional utilities for market-division & bid-rigging cartels.

- Leniency first-in wins: the initiator gained 100 % immunity, underscoring the strategic value of self-reporting.

- Courts, regulators and industry players now face questions on market definition, repeat offenses, and post-2020 AMA surcharge multipliers.

Table of Contents

- Market Liberalisation & Background

- JFTC Findings: Three Separate Cartels

- Surcharge Calculations & Leniency Math

- Legal Issues: Market Definition, Ringleader Immunity, Remedies

- Compliance Takeaways for Regulated Industries

- Japan vs. U.S. Cartel Enforcement

Competition law enforcement in Japan reached a new high-water mark in early 2023 when the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC), the country's antitrust watchdog, imposed unprecedented administrative surcharges totaling approximately ¥101 billion (around USD 750 million at the time) against several major power companies. This decision, stemming from alleged cartel activity in the newly liberalized retail electricity market, represents the largest aggregate surcharge ever levied under Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA). The case not only highlights the JFTC's commitment to tackling anticompetitive conduct but also raises significant questions about market definition, the application of the leniency program, and the interplay between competition law and sector regulation. Understanding the intricacies of this case offers valuable lessons for businesses operating in Japan, particularly those in regulated or recently liberalized industries.

Background: Liberalization and Competition in Japan's Electricity Market

For decades, Japan's electricity market was dominated by ten regional monopolies, known as General Electricity Utilities (旧一般電気事業者, kyū ippan denki jigyōsha). Starting in the early 2000s and accelerating significantly by 2016, Japan undertook a phased liberalization of its retail electricity market, aiming to introduce competition, lower prices, and provide greater choice for consumers, including large industrial users and eventually households.

This liberalization allowed new players to enter the market and permitted the former regional monopolies to compete outside their traditional service areas. While intended to foster competition, this transition also created incentives for the incumbent utilities, facing new competitive pressures, to potentially coordinate their activities to protect market share and pricing levels in their respective home territories. It was within this context that the JFTC initiated its investigation.

The JFTC Investigation and Findings

On March 30, 2023, the JFTC issued cease-and-desist orders and surcharge payment orders against several former General Electricity Utilities. The investigation, reportedly triggered by a leniency application, uncovered three distinct sets of agreements aimed at limiting competition, primarily centered around a major utility based in the Kansai region coordinating with counterparts in the Chubu, Chugoku, and Kyushu regions.

The JFTC found that these utilities had engaged in conduct constituting an "unreasonable restraint of trade" (不当な取引制限, futō na torihiki seigen) under Article 2, Paragraph 6 of the AMA – Japan's primary provision prohibiting cartels. The specific anticompetitive agreements included:

- Market Division (between Kansai/Chubu and Kansai/Chugoku): Agreements where the participating utilities mutually agreed to refrain from or limit actively soliciting large-scale, high-voltage electricity customers located within each other's traditional geographic supply areas. The objective, according to the JFTC, was to prevent price erosion by avoiding aggressive price competition for these significant customers.

- Bid Rigging / Customer Allocation (between Kansai/Chugoku and Kansai/Kyushu): Agreements involving restrictions on participating in, or submitting aggressively low bids for, public tenders (e.g., contracts for government facilities) within each other's traditional areas. The Kansai/Chugoku agreement also included restrictions on soliciting certain non-tender ("relative") customers. The aim was again to prevent price competition and secure contracts within their respective regions.

The JFTC concluded that these agreements, designed to mutually restrict business activities and artificially maintain price levels, substantially restrained competition in specific fields of trade related to the supply of electricity to certain customer segments within defined geographic areas.

Record Administrative Surcharges (Kachōkin)

A key feature of Japanese antitrust enforcement is the JFTC's power to impose administrative surcharges (課徴金, kachōkin). Unlike punitive fines common in US criminal antitrust cases, kachōkin are primarily intended to disgorge the illicit gains derived from the anticompetitive conduct and act as a deterrent. The amount is typically calculated as a percentage of the relevant sales of goods or services affected by the violation during the infringement period.

In this case, the JFTC levied surcharges against four companies: Chubu Electric Power Mirise (a retail subsidiary of Chubu Electric), Chugoku Electric Power, and Kyushu Electric Power, along with one of its subsidiaries. The total sum reached approximately ¥101 billion, shattering previous records.

- Immunity and Reductions: Notably, the Kansai-based utility, which initiated the leniency application, received full immunity from surcharges. Chubu Electric Power itself was not fined as the relevant retail business had been transferred to its subsidiary (Chubu Mirise) which was fined. Kyushu Electric Power, having applied for leniency after the Kansai utility but cooperating with the investigation, received a 30% reduction in its surcharge. A Kyushu Electric subsidiary involved was not fined as it had no relevant sales during the calculation period.

- Calculation Nuances: The timing of the violation (ending before the effective date of major AMA amendments in December 2020) meant that older, generally lower, base calculation rates applied. However, Kyushu Electric's leniency reduction was calculated under the new rules introduced by the 2019 AMA amendments (effective December 2020), which allow for reductions based on the degree of cooperation provided. This blend of old base rates and new leniency rules highlights the transitional complexities following AMA reforms. Had the new, potentially higher, base rates and rules regarding aggravating factors (like ringleader status) fully applied, the fines could conceivably have been even larger.

The Critical Role of the Leniency Program

This case vividly demonstrates the power and significance of Japan's leniency program (課徴金減免制度, kachōkin genmen seido). Introduced in 2006 and reformed significantly in 2009 and 2019, the program provides full immunity from surcharges for the first party to self-report a cartel to the JFTC and provide qualifying information and cooperation, with subsequent applicants potentially receiving partial reductions.

The JFTC explicitly stated that the Kansai-based utility received full immunity as the first leniency applicant. Kyushu Electric and its subsidiary jointly applied later, securing the 30% reduction under the cooperation-based system introduced by the latest amendments. Without the leniency applications, particularly the first one, it is possible this large-scale, high-level coordination might have remained undetected or been significantly harder for the JFTC to prosecute effectively. It underscores the program's effectiveness in destabilizing cartels by creating a strong incentive for participants to break ranks and report the conduct.

Key Legal and Policy Issues

The JFTC's decision, while clear in its condemnation of the conduct, raises several interesting legal and policy questions that were noted in contemporary legal commentary:

1. Market Definition and Number of Violations:

Instead of treating the interlocking agreements as a single nationwide or multi-regional conspiracy among incumbents, the JFTC defined three separate relevant markets based on the pairings (Kansai/Chubu, Kansai/Chugoku, Kansai/Kyushu) and treated the conduct as three distinct violations. This approach might reflect the differing specifics of each bilateral agreement (pure market division vs. bid rigging vs. hybrid).

However, this fragmented approach could be questioned. From the perspective of a large customer in the Kansai region, for instance, both the Chubu and Chugoku utilities might be seen as potential alternative suppliers. Treating the competitive constraints as purely bilateral might not fully capture the market dynamics. Furthermore, dividing the conduct into three separate violations could, theoretically, lead to complexities in surcharge calculation, potentially resulting in overlapping calculations for the Kansai utility (though this was moot due to its full immunity). Consistency in market definition across related conduct is a common challenge in antitrust analysis.

2. Leniency for the Initiator:

Reports suggest the Kansai-based utility played a central role and initiated the approaches to its regional counterparts. This raises the question of whether granting full immunity was appropriate under the AMA's leniency framework. The AMA (Article 7-4, Paragraph 5, Item 4) allows the JFTC to deny leniency to a party that "coerced" (強要, kyōyō) others into participating in the violation. The JFTC presumably concluded that the Kansai utility's actions did not meet the high threshold of "coercion," which likely requires threats or illegitimate pressure beyond mere initiation or persuasion. This aligns with international practice, where leniency is often available even to instigators unless genuine coercion is involved, recognizing that ringleaders often possess the most valuable evidence.

Separately, the AMA allows for an increase in the surcharge calculation rate for parties playing a "leading role" (主導的役割, shudōteki yakuwari) (Article 7-3, Paragraph 2). While leniency trumped any potential increase here, legal commentary suggested that, based on the facts, the Kansai utility's conduct might well have qualified for such an increase had it not secured immunity.

3. No Cease-and-Desist Order for the Leniency Applicant:

A consistent practice of the JFTC is to generally refrain from issuing cease-and-desist orders (排除措置命令, haijo sochi meirei) against recipients of full leniency immunity. This held true here, with the Kansai utility escaping such an order despite its pivotal role. Cease-and-desist orders aim to eliminate the lingering effects of the violation and prevent its recurrence. While distinct from the punitive/disgorgement purpose of kachōkin, the automatic exemption of leniency applicants, particularly initiators or those whose conduct might warrant structural or behavioral remedies, is debated. Critics argue that ensuring future competition might sometimes require imposing specific conduct restrictions even on cooperating parties, and that relying solely on industry self-policing or sector regulators might be insufficient, especially where entrenched industry practices contributed to the violation. The JFTC did, however, make recommendations to the relevant industry association and liaised with the sector regulator, the Electricity and Gas Market Surveillance Commission.

Implications for Businesses

The JFTC's handling of the electricity cartel case sends several strong messages to businesses operating in Japan:

- Aggressive Enforcement: The JFTC is willing and able to tackle complex, high-level cartel conduct, even in industries undergoing significant regulatory change. The record surcharges demonstrate a low tolerance for hard-core restrictions like market division and bid rigging.

- Substantial Financial Risk: Violations of the AMA carry enormous financial exposure. The kachōkin system can result in fines amounting to a significant percentage of a company's revenue derived from the affected products or services over several years.

- Compliance is Critical: Robust antitrust compliance programs are not optional. This includes educating employees at all levels about prohibited conduct, establishing clear reporting channels, and potentially conducting internal audits, especially in concentrated industries or those with a history of cooperation among competitors.

- Strategic Importance of Leniency: The leniency program remains a crucial element of the enforcement landscape. Companies uncovering potential cartel involvement face difficult strategic decisions regarding self-reporting, weighing the benefits of potential immunity or reduction against the costs and risks of investigation and potential follow-on damages actions (which are becoming more feasible in Japan).

Comparison with US Antitrust Enforcement

While both Japan and the US vigorously prosecute cartels, there are some differences in approach:

- Criminal vs. Administrative: Hard-core cartel conduct like price-fixing, bid rigging, and market allocation are per se criminal felonies in the US, often leading to large corporate fines and individual prison sentences. While the JFTC can make criminal referrals to prosecutors, its primary tool is the administrative process involving cease-and-desist orders and kachōkin. Criminal prosecution for AMA violations is less frequent than in the US.

- Fines/Surcharges: US criminal fines are determined under sentencing guidelines considering factors like culpability, volume of commerce, and duration, potentially leading to very large fines. Japan's kachōkin are calculated based on affected sales, with rates specified in the AMA, aiming primarily at disgorgement but achieving significant deterrent effects through their potential size.

- Leniency: Both jurisdictions have highly effective leniency programs offering immunity to the first qualifying applicant and potential reductions for subsequent cooperators. Japan's recent AMA amendments have incorporated cooperation levels more explicitly into reduction calculations, mirroring aspects of the US system.

- Remedies: The JFTC primarily uses cease-and-desist orders for prohibitive relief. US enforcement (both DOJ and FTC) uses injunctions obtained through court proceedings and may require more structural or behavioral remedies in settlements or court orders.

Conclusion

The Japanese electricity cartel case stands as a landmark decision, demonstrating the JFTC's resolve to enforce the Antimonopoly Act rigorously and impose substantial financial penalties for hard-core violations. The record-breaking ¥101 billion in surcharges underscores the significant risks faced by companies engaging in anticompetitive agreements. The case also highlights the pivotal role of the leniency program in uncovering such conduct, while simultaneously sparking debate about its application, particularly regarding ringleaders and the scope of remedies beyond monetary penalties. For businesses operating in or interacting with the Japanese market, this case serves as a stark reminder of the critical need for effective antitrust compliance and the potentially severe consequences of engaging in cartel behavior. The JFTC has clearly signaled its continued vigilance in protecting competition, even within complex and evolving industry structures.