Japan Tightens Shareholder Transparency: What the 2024 Large Shareholding Report Reforms Mean for Investors

TL;DR: Japan’s 2024 amendment cuts the Large Shareholding Reporting (LSR) threshold from 5 % to 3 %, shortens the filing window to three business days, and expands derivative and joint-holder coverage. Global investors must upgrade monitoring systems and prepare for real-time disclosure.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why LSR Reform Matters

- Key Changes Under the 2024 Amendment

- Derivative and Joint-Holder Expansion

- Compliance Timeline and Transitional Measures

- Practical Implications for Investors

- Conclusion: Toward Greater Market Transparency

Introduction

Transparency is a cornerstone of well-functioning capital markets, enabling investors to make informed decisions and promoting market integrity. In Japan, the Large Shareholding Reporting (LSR) system, mandated by the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA), serves as a primary mechanism for achieving this transparency regarding significant ownership stakes in listed companies. However, the LSR system has faced challenges in keeping pace with evolving investment strategies and the growing emphasis on corporate governance and shareholder engagement.

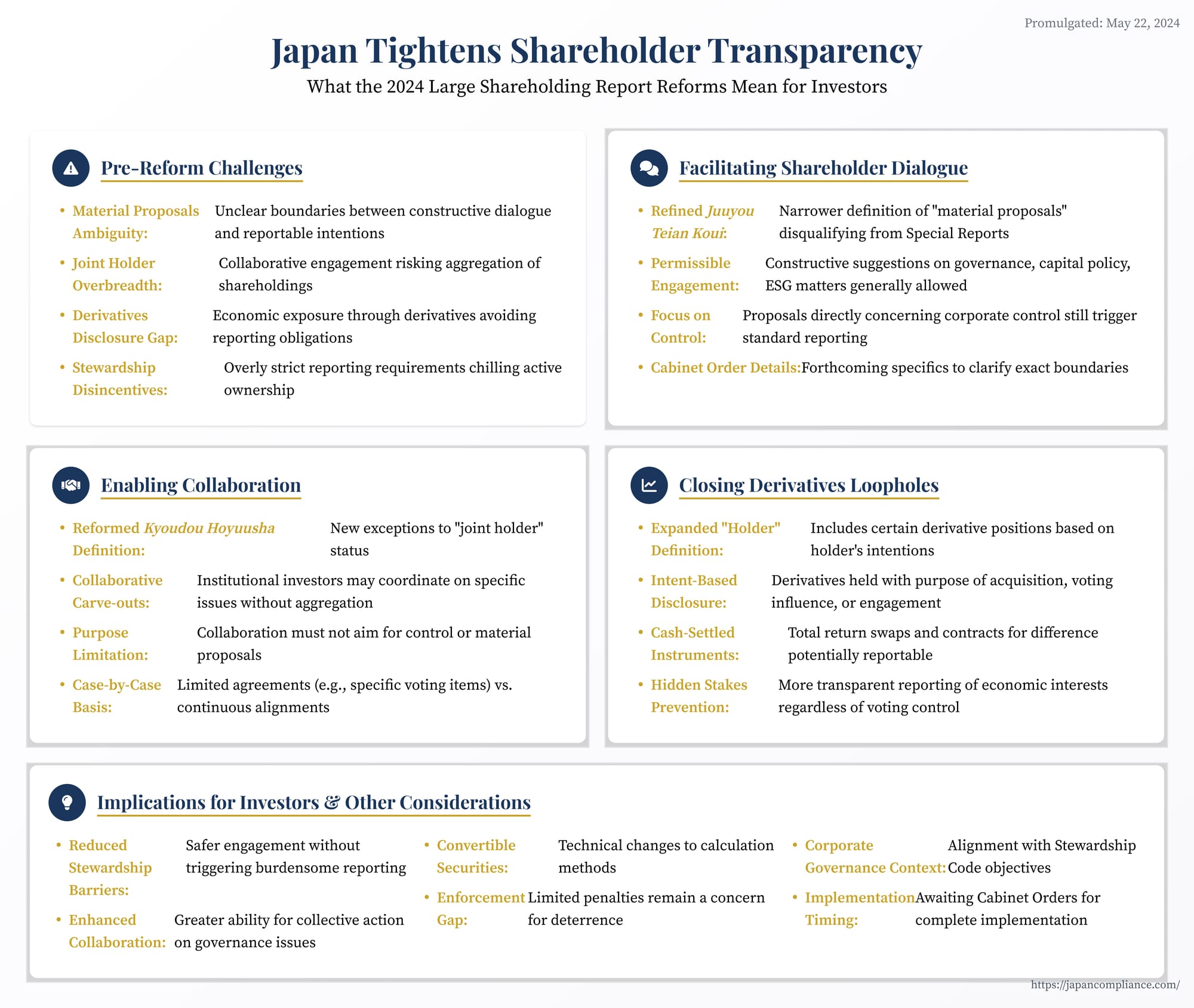

Recognizing these challenges, Japan enacted significant amendments to the FIEA in May 2024 (Act No. 32 of 2024), which include targeted reforms to the LSR rules. These changes, largely based on the December 2023 report from the Financial System Council's Working Group, aim to strike a delicate balance: enhancing meaningful transparency while simultaneously facilitating, rather than hindering, constructive dialogue between investors and investee companies.

The key reforms focus on clarifying ambiguous definitions that previously hampered shareholder engagement, expanding disclosure requirements to capture economic interests held through derivatives, and refining the concept of joint shareholding in the context of collaborative investor initiatives. This article delves into these critical changes to the LSR system and analyzes their implications for domestic and international investors operating in the Japanese market.

1. The Large Shareholding Reporting (LSR) System: Purpose and Pre-Reform Challenges

Japan's LSR system fundamentally requires any person whose holding ratio (hoyuuhoukokusho) of voting shares and related instruments in a publicly listed company exceeds 5% to file a Large Shareholding Report (tairyou hoyuu houkokusho) with the regulatory authorities within five business days. This report, publicly available through the EDINET system, must disclose the holder's identity, the number of shares held, the purpose of holding (hoyuu mokuteki), funding sources, and details of any "joint holders" (kyoudou hoyuusha). Subsequent changes in the holding ratio of 1% or more, or changes in previously reported material information (like holding purpose or joint holders), trigger the filing of an Amendment Report (henkou houkokusho).

The system's stated objectives are twofold:

- Market Transparency: To provide the market (including other investors and the issuer) with timely information about the existence of significant shareholders and their potential influence or intentions regarding the company.

- Investor Protection: To allow investors to make informed judgments based on the knowledge of who holds substantial stakes and whether changes in control or strategy might be forthcoming.

The Special Reporting Regime (Tokurei Houkoku)

A key feature is the Special Reporting system available under FIEA Article 27-26 for eligible institutional investors (such as banks, insurance companies, investment managers, trust banks). If these investors hold shares purely for investment purposes and do not intend to make "material proposals" (juuyou teian koui) concerning the issuer's business activities or exert significant influence, they can opt for a less frequent reporting schedule. Instead of filing within five days of every 1% change, they typically file reports based on holdings as of two fixed calculation dates per month, submitting the report within five business days thereafter. This significantly reduces the administrative burden for passive institutional investors.

Pre-Reform Challenges

Despite its aims, the LSR system faced growing criticism regarding certain ambiguities and gaps:

- "Material Proposals" Ambiguity: The lack of clarity on what constituted a "material proposal" created uncertainty for institutional investors committed to active ownership and engagement under Japan's Stewardship Code. Engaging in dialogue about governance, strategy, or ESG matters risked being interpreted as intending material proposals, potentially disqualifying them from the less burdensome Special Reporting regime and thus chilling constructive dialogue.

- "Joint Holder" Overbreadth: The definition of joint holders based on an "agreement" (goui) to act together could be interpreted broadly, potentially capturing collaborative engagement efforts among multiple investors on shared concerns (e.g., climate risk disclosure). This risked imposing significant reporting burdens (tracking aggregated holdings, complex information sharing) and revealing strategic coordination, discouraging legitimate collaboration.

- Derivatives Disclosure Gap: Investors could amass substantial economic exposure to a company using cash-settled derivatives (like total return swaps) without holding the underlying shares or voting rights, thereby potentially avoiding LSR disclosure obligations despite having significant economic interests or potential influence.

The 2024 FIEA reforms directly address these three core challenges.

2. Key Reform 1: Facilitating Shareholder Dialogue – Refining "Material Proposals"

The reform seeks to clarify the boundary between constructive engagement and actions triggering stricter reporting obligations.

- The Link: Eligibility for the simplified Special Reporting regime hinges on the investor not holding shares for purposes that include making "material proposals" concerning the issuer's business (FIEA Art. 27-26, Para. 1). Such proposals are defined in Article 14-8-2 of the FIEA Cabinet Order and include items like proposing significant changes to business objectives, dividend policies, major reorganizations, or nominating/opposing directors.

- The Problem: Before the reform, investors feared that suggesting improvements in areas like capital efficiency, board independence, or climate strategy – activities encouraged by the Stewardship Code – could be construed as falling under the existing broad categories of "material proposals." This uncertainty acted as a significant deterrent to robust engagement, as investors wished to avoid the operational complexities of standard reporting triggered by crossing the subjective line of "material proposal" intent. Previous guidance from the Financial Services Agency (FSA) attempted to clarify that general dialogue was permissible, but ambiguity persisted.

- The Reform's Direction (via forthcoming Cabinet Order): While the FIEA itself wasn't heavily amended on this point, the legislative intent, guided by the WG report, is to refine the Cabinet Order definition of "material proposals" that disqualify investors from Special Reporting. The anticipated changes aim to differentiate more clearly between:

- Actions likely remaining disqualifying: Proposals directly concerning corporate control (e.g., significant share acquisitions aimed at control, proxy fights for board control) or proposals intended to bind management's actions without leaving them discretion.

- Actions likely becoming permissible under Special Reporting: Constructive dialogue, suggestions, or recommendations regarding strategy, governance, capital policy, or ESG matters where the ultimate decision rests with the company's management. The focus shifts towards the nature and binding effect of the investor's action, rather than just the topic discussed.

- Implications: This clarification is expected to lower the perceived regulatory risk associated with active engagement for institutional investors. By providing greater certainty that constructive dialogue will not automatically trigger more onerous reporting, the reform aims to foster more meaningful communication between shareholders and management, aligning the LSR system more closely with Japan's broader corporate governance objectives. The precise wording of the revised Cabinet Order will be crucial in determining the practical impact.

3. Key Reform 2: Enabling Collaboration – Refining "Joint Holders"

The reform addresses concerns that the previous definition of "joint holders" inadvertently penalized collaborative stewardship efforts.

- The Aggregation Rule: Holdings of parties deemed "joint holders" are aggregated for the 5% threshold calculation. The definition hinges on an "agreement" (goui) to jointly acquire/dispose of shares or exercise shareholder rights (FIEA Art. 27-23, Para. 5).

- The Problem: "Agreement" could encompass informal understandings or coordinated approaches. When multiple institutional investors collaborated on common concerns (e.g., jointly requesting enhanced climate disclosures from portfolio companies), they risked being classified as joint holders. This status would necessitate constant communication to monitor their aggregated holdings (potentially exceeding 5% or changing by 1% collectively) and file reports, a significant operational burden that also risked revealing their coordinated strategy prematurely. This "chilling effect" discouraged potentially beneficial collective action on systemic governance or sustainability issues.

- The Reform (FIEA Amendment & forthcoming Government Ordinance): The FIEA (Art. 27-23, Para. 5) was amended to introduce the possibility of excluding certain situations from the joint holder definition, with specifics delegated to government ordinances. The legislative intent is to create a carve-out for collaborative engagement activities, primarily among institutional investors, under specific conditions:

- Eligible Investors: The carve-out will likely apply only to certain regulated financial institutions (banks, investment managers, etc.) specified in the ordinance.

- Purpose Limitation: The purpose of the collaboration or agreement must not be to jointly make "material proposals" (as discussed above) or to seek management control.

- Nature of Agreement: The agreement should pertain to the joint exercise of rights on a limited, typically case-by-case basis (e.g., agreeing to vote a certain way on a specific resolution at a specific meeting), rather than constituting a continuous, binding alignment of voting or engagement strategy across the board.

- Implications: This reform aims to provide a safer harbor for institutional investors engaging in collective stewardship. By excluding specific forms of collaboration focused on dialogue or issue-specific voting from the joint holder aggregation, it should reduce the administrative hurdles and disincentives previously associated with such activities. This could empower investors to work together more effectively on promoting better corporate practices across their portfolios. However, the exact boundaries of the carve-out (e.g., how "continuous" agreement is defined) will depend on the forthcoming ordinance.

4. Key Reform 3: Closing Loopholes – Enhancing Derivatives Disclosure

The reform tackles the potential for investors to use derivatives to gain substantial economic exposure while avoiding LSR filing requirements.

- The Issue: An investor could use instruments like cash-settled total return swaps or contracts for difference to replicate the economic risks and rewards of owning a large block of shares without actually holding title to the shares or possessing voting rights. Under the old rules, unless the investor could be deemed to have effective "control" over the underlying shares (e.g., dictating how the counterparty, often a broker holding shares as a hedge, voted or disposed of them), this economic interest might not trigger an LSR filing, masking the investor's significant financial stake and potential influence from the market.

- Previous Interpretations: FSA guidance acknowledged this issue but often focused on whether the derivative holder exercised practical control over the shares held by the counterparty, which could be difficult to establish.

- The Reform (FIEA Amendment & forthcoming Government Ordinance): The definition of "Holder" (hoyuusha) in FIEA Art. 27-23, Para. 3 has been explicitly expanded. A new Item 3 brings certain derivative positions within the scope of reportable holdings, even if cash-settled and without direct control over underlying shares, if they are held with specific intents. These critical intents, to be detailed in a Cabinet Order, are expected to include holding the derivative:

- With the purpose of eventually acquiring the underlying shares from the counterparty.

- With the purpose of influencing the exercise of voting rights attached to the shares held by the counterparty (e.g., shares held as a hedge).

- With the purpose of engaging with the issuer (e.g., demanding changes) based on the leverage or position provided by the derivative holding.

- Implications: This change significantly enhances transparency by requiring disclosure of substantial economic interests acquired through derivatives when coupled with specific intentions related to ownership, voting influence, or engagement. It makes it harder to build "hidden stakes" and aligns disclosure obligations more closely with economic reality and potential market impact. However, the practical challenge will lie in determining or proving the investor's "purpose" or "intent," which may require careful scrutiny of trading patterns, communications, and surrounding circumstances by regulators.

5. Other Adjustments and Considerations

- Calculation for Convertible Securities: A technical amendment (to FIEA Art. 27-23, Para. 4, implemented via Cabinet Office Ordinance) clarifies the calculation method for holding ratios involving shares with conversion rights or acquisition rights (shutoku seikyuuken-tsuki kabushiki, etc.). The calculation will now generally be based on the number of shares after assuming the rights have been exercised, if that number is greater than the number of shares held before exercise, ensuring the maximum potential voting power is reflected.

- Enforcement: While the substantive rules have been refined, the enforcement mechanisms for LSR violations remain largely unchanged by the 2024 FIEA amendments. The low level of kachoukin penalties continues to be a concern regarding deterrence, although recent administrative actions might signal a stricter approach. The WG's discussion on potentially introducing voting right suspensions for LSR violations did not translate into legislative change, leaving a gap compared to enforcement tools available in some other jurisdictions.

- Broader Context: These LSR reforms should be viewed within the wider context of Japan's corporate governance evolution, including the emphasis on the Stewardship Code and the drive for more constructive investor-company dialogue. They also complement the TOB reforms by ensuring greater transparency around significant stake accumulations that might precede a control transaction.

Conclusion

The 2024 FIEA amendments introduce crucial refinements to Japan's Large Shareholding Reporting system, aiming to enhance market transparency while simultaneously supporting productive shareholder engagement. By clarifying the ambiguous scope of "material proposals," refining the definition of "joint holders" to accommodate collaborative stewardship, and expanding disclosures to capture significant economic interests held via derivatives, the reforms seek to modernize the LSR framework for today's capital markets.

The overarching goal appears to be fostering a market environment where transparency informs, rather than inhibits, the responsible exercise of ownership rights and constructive dialogue between investors and corporate management. While the reforms represent a positive step, their ultimate success will depend on the precise details implemented through forthcoming government ordinances and the effectiveness of regulatory oversight and enforcement.

For all investors in Japanese equities, particularly institutional investors navigating stewardship responsibilities and those employing sophisticated financial instruments, understanding these updated LSR rules is paramount. Careful attention to the nuances of holding purpose, collaborative agreements, and derivative strategies, along with the specific definitions set forth in upcoming ordinances, will be essential for compliance and effective participation in the Japanese market.

- Japan’s 2024 FIEA Reforms: Key Changes to Takeover Bids and Large-Shareholding Reports

- Mandatory Tender Offers in Japan: Expanded Scope under the 2024 FIEA Amendments

- Antitrust Oversight in Japanese M&A: Understanding Merger Control and the Role of Monitoring Trustees

- Financial Services Agency — 2024 Large Shareholding Report Reform Outline (JP)

https://www.fsa.go.jp/news/r6/20240522/large_shareholding_reform.html