Japan Targets Mobile Ecosystems: Inside the Smartphone Software Competition Promotion Act

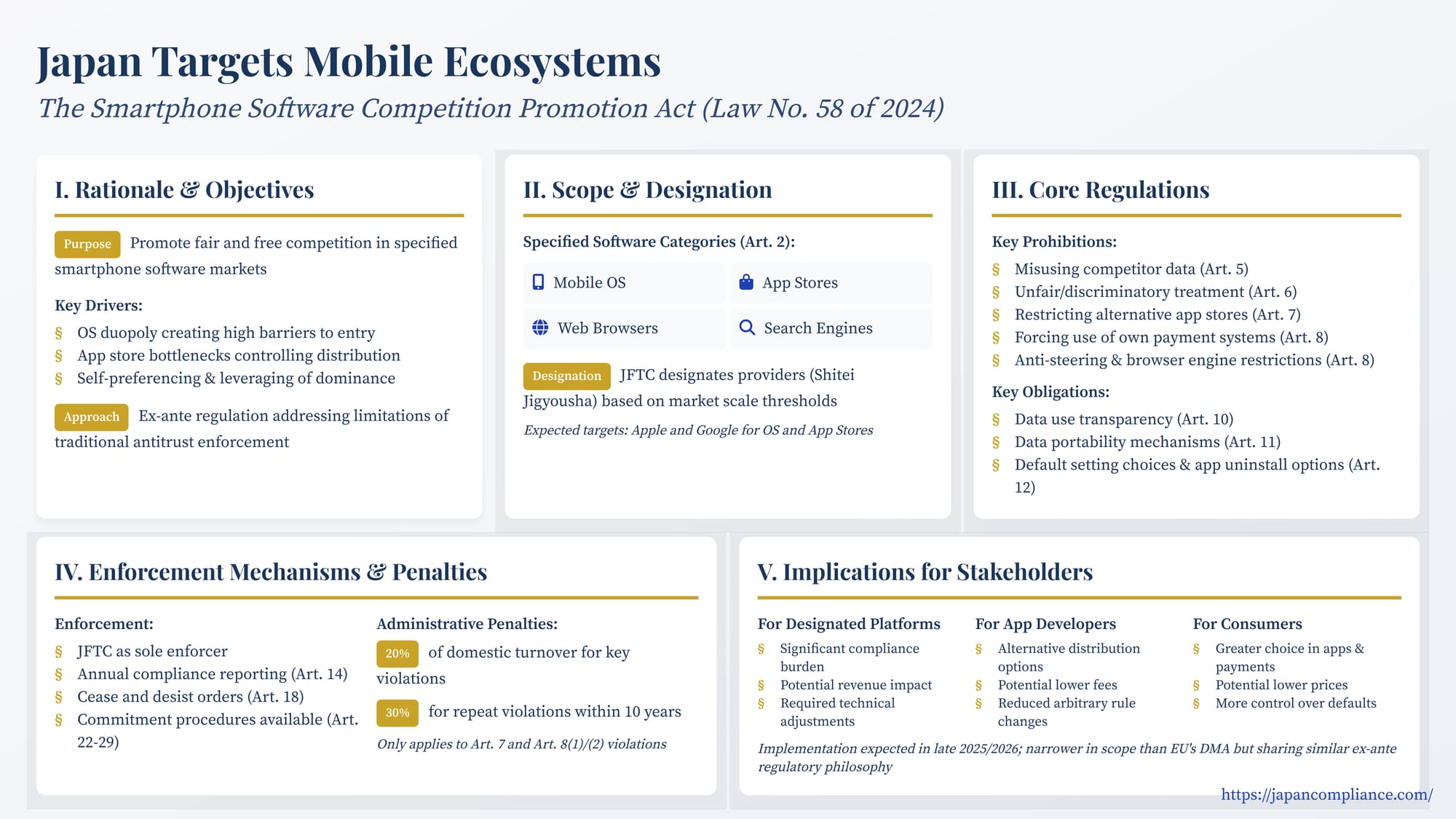

TL;DR: Japan’s Smartphone Software Competition Promotion Act channels EU-style ex-ante rules into mobile OS, app-store, browser and search markets. Designated gatekeepers face strict anti-self-preferencing and anti-tying bans, data-portability and default-choice mandates, plus up to 20 % turnover fines. Full enforcement is expected in 2026—global tech firms must prep compliance roadmaps now.

Table of Contents

- Why a New Law? Rationale and Objectives

- Scope and Designation: Who is Covered?

- Core Regulations: Obligations and Prohibitions

- Enforcement and Penalties

- Implications and Analysis

- Conclusion

Introduction

Smartphones have become the indispensable hubs of our digital lives, mediating access to information, communication, entertainment, and commerce. However, the very ecosystems that make these devices so powerful—primarily the mobile operating systems (OS) and application stores (app stores)—are dominated globally by just two major players. This concentration of power has raised significant concerns among regulators worldwide about potential anti-competitive practices that could stifle innovation, limit consumer choice, and disadvantage smaller businesses like app developers.

Joining a global trend spearheaded by the European Union's Digital Markets Act (DMA), Japan has taken decisive action by enacting the "Act on Promoting Competition for Specified Smartphone Software" (スマートフォンにおいて利用される特定ソフトウェアに係る競争の促進に関する法律, Law No. 58 of 2024). Enacted in June 2024 and promulgated on June 19, 2024, this landmark legislation (hereinafter "the Act" or "Smartphone Software Act") introduces a new regulatory framework specifically designed to address competition issues within Japan's crucial mobile ecosystems.

The Act moves beyond traditional antitrust enforcement by establishing ex-ante rules—specific obligations and prohibitions—for designated large providers of core smartphone software. While inspired by international models, it carves out a distinct Japanese approach. For global technology companies, app developers, and any business reliant on the mobile ecosystem in Japan, understanding the intricacies of this new law is critical. This article provides an in-depth analysis of the Act's objectives, scope, core regulations, enforcement mechanisms, and potential implications as Japan prepares for its full implementation (expected in late 2025 or 2026).

1. Why a New Law? Rationale and Objectives

The enactment of the Smartphone Software Act stems from a recognition by Japanese authorities that existing laws, primarily the Antimonopoly Act (AMA), were potentially insufficient to address the unique competition challenges posed by dominant digital platforms in the fast-moving mobile sector.

- Identified Competition Problems: The key catalyst was the "Final Report on Competition Assessment of the Mobile Ecosystem," published by Japan's Headquarters for Digital Market Competition (デジタル市場競争会議) on June 16, 2023. This report highlighted several concerns:

- OS Duopoly: The dominance of two major mobile OS providers creates high barriers to entry and locks users into specific ecosystems.

- App Store Bottleneck: These OS providers also control the primary app stores, giving them gatekeeper power over app distribution, discovery, and monetization.

- Leveraging Dominance: Concerns that dominant players leverage their control over foundational layers (OS, app stores, browsers, search engines) to disadvantage competing apps or services, often through self-preferencing or restrictive terms.

- Interlocking Issues: Problems across different layers (e.g., restrictions on browser engines within an OS affecting web app competition) create interconnected barriers that reinforce the incumbents' positions.

- Limitations of Traditional Antitrust (AMA): Relying solely on the AMA to tackle these issues presented difficulties:

- Proof Burden: Establishing anti-competitive effects under the AMA often requires complex market definition and economic analysis, which can be challenging and time-consuming in dynamic digital markets.

- Speed of Enforcement: Investigations and legal proceedings under the AMA can be lengthy. By the time a remedy is imposed, the market may have "tipped," and the competitive harm may be irreversible. The EU's experience prior to the DMA, facing similar challenges in bringing timely and effective antitrust cases against Big Tech, heavily influenced this perspective in Japan.

- Act's Stated Objective (Article 1): The Smartphone Software Act explicitly aims "to promote fair and free competition related to specified software used in smartphones." By setting clear, upfront rules for dominant players, it seeks to preemptively address potentially harmful conduct, foster innovation by third-party businesses, and ultimately benefit consumers through greater choice and potentially lower prices. It represents a shift towards proactive, sector-specific regulation for a market deemed critical to Japan's digital economy.

2. Scope and Designation: Who is Covered?

The Act employs a two-stage regulatory approach, first identifying core software categories and then designating specific large providers within those categories to be subject to the main obligations.

- "Specified Software" (Article 2): The law targets four types of software deemed essential to the smartphone user experience:

- Mobile Operating Systems (OS): Referred to as kihon dousa software ("basic operating software").

- App Stores: Platforms for distributing applications (kobetsu software).

- Web Browsers.

- Search Engines: Specifically those used for searching "unspecified websites" (excluding site-specific search tools).

- "Designated Providers" (Shitei Jigyousha) (Article 3): The Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) is tasked with designating specific business operators ("Specified Software Business Providers") for each category. Designation requires meeting certain size thresholds related to the scale of their business in Japan (e.g., number of users, transaction volumes). These specific thresholds will be defined by forthcoming Cabinet Orders.

- Expected Targets: Given the market structure, it is widely anticipated that global tech giants Apple and Google will be among the first designated providers for OS and App Stores, and potentially other categories like Browsers and Search Engines, depending on the final threshold criteria.

- Significance of Designation: Only providers formally designated by the JFTC will be subject to the core prohibitions and obligations outlined in Chapter 3 of the Act. This designation process provides clarity on who falls under the stringent ex-ante regime. (Note: The legal provisions related to designation procedures were scheduled to come into force by December 2024, preceding the full implementation of the substantive rules).

3. Core Regulations: Obligations and Prohibitions (Articles 5-13)

Chapter 3 of the Act lays out specific "do's and don'ts" for designated providers, tailored to address the competition concerns identified in the mobile ecosystem. These rules generally apply without requiring the JFTC to prove anti-competitive effects in each specific instance.

3.1. Key Prohibitions (Articles 5-9)

Designated providers are prohibited from engaging in certain types of conduct:

- Misusing Competitor Data (Art. 5): Prohibits using non-public data acquired from business users (e.g., app developers using the platform) for the benefit of the designated provider's own competing services. This aims to prevent platforms from unfairly leveraging data gleaned from third parties operating on their ecosystem.

- Unfair/Discriminatory Treatment (Art. 6): A general clause prohibiting designated OS or App Store providers from unfairly discriminating against or otherwise treating business users unfairly regarding terms, conditions, or implementation. This mirrors similar concepts in general competition law but applied specifically here without needing a full effects analysis. Justification may be considered more broadly under this article.

- OS Provider Prohibitions (Art. 7):

- Restricting Alternatives: Prohibits forcing the use of the provider's own app store (e.g., preventing installation of competing app stores) or hindering the use of competitor apps/services by limiting their functionality compared to the provider's own offerings (addressing interoperability concerns).

- App Store Provider Prohibitions (Art. 8):

- Forcing Own Systems: Prohibits requiring app developers to use the platform's own in-app payment system exclusively.

- Anti-Steering Restrictions: Prohibits preventing developers from informing users about, or linking to, offers available outside the app store (e.g., on their own websites, potentially at lower prices).

- Browser Engine Restrictions: Prohibits preventing app developers from using browser engines other than the one specified by the platform operator within their apps.

- Discriminatory Application of Rules: Prohibits unfairly applying app review guidelines or user identity verification systems in a way that disadvantages competing apps.

- Search Provider Prohibitions (Art. 9): Prohibits unfairly prioritizing the designated provider's own services over those of competitors in general search results display without a justifiable reason.

3.2. Key Affirmative Obligations (Articles 10-13)

Designated providers are required to take certain positive steps:

- Data Access/Use Disclosure (Art. 10): Obligation to disclose to business users the conditions under which the platform acquires or uses their data. Also requires facilitating disclosure of data acquisition conditions by other business users (potentially relevant for ad networks, etc.). A separate clause requires disclosure to end-users regarding data handling.

- Data Portability (Art. 11): Obligation to establish measures enabling users to smoothly transfer data acquired through the platform upon the user's request, aimed at reducing switching costs.

- Default Settings and App Choice (Art. 12):

- OS/Browser: Must allow users to easily change default settings (e.g., default browser) and provide choice screens presenting alternatives during initial setup or use.

- OS: Must allow users to easily uninstall pre-installed applications (with exceptions for those essential for OS functionality). Must obtain user consent before installing additional apps during OS updates.

- Fair Procedures (Art. 13): Obligation to establish fair procedures, provide necessary information, and ensure appropriate systems when setting or changing terms of use or refusing service related to the specified software. This addresses concerns about arbitrary changes impacting business users.

3.3. Justifications and Exceptions (Articles 7 & 8)

A crucial aspect is the limited scope for justifying conduct that would otherwise violate certain core prohibitions (specifically those in Art. 7 regarding OS restrictions and Art. 8(1)-(3) regarding app store payment/linking/browser engine restrictions). The Act permits such conduct only if it is deemed necessary for specific, enumerated purposes and there is no less restrictive alternative means to achieve that purpose. The recognized purposes are:

- Ensuring cybersecurity (saibaa sekyuriti no kakuho).

- Protecting privacy and personal information.

- Protecting youth (seishounen no hogo).

- Other reasons specified by Cabinet Order (intended for genuinely essential technical reasons, not broad loopholes).

This sets a high bar for designated providers seeking to justify potentially anti-competitive restrictions based on security or privacy grounds, reflecting a policy choice prioritizing the opening of competition in these core areas. The JFTC's interpretation and application of this stringent necessity test will be critical.

4. Enforcement and Penalties

The Act grants the JFTC significant enforcement powers, combining elements from both the AMA and the Transparency Act.

- JFTC as Enforcer: The JFTC is the sole authority responsible for designating providers and enforcing the Act's obligations and prohibitions.

- Annual Compliance Reporting (Art. 14): Designated providers must submit annual reports to the JFTC detailing their compliance efforts, providing a basis for ongoing monitoring.

- Orders (Art. 18): If the JFTC finds a violation of the prohibitions (Art. 5-9) or a failure to take the required measures (Art. 10-13), it can issue cease and desist orders or orders mandating necessary actions.

- Administrative Monetary Penalties (Kachoukin) (Art. 19): This is a major feature, designed for strong deterrence.

- High Rate: The penalty is set at 20% of the domestic turnover generated from the business related to the specific violation during the violation period.

- Escalation: For repeat violations within 10 years, the rate increases by 50%, leading to a 30% penalty rate.

- Limited Scope: Crucially, these high penalties apply only to violations of Article 7 (OS restrictions on alternatives/interoperability) and Articles 8(1) and 8(2) (App Store restrictions on payments and linking out). Violations of other prohibitions (e.g., self-preferencing in search under Art. 9, discriminatory treatment under Art. 6) or failures to meet affirmative obligations (Art. 10-13) are not subject to kachoukin under this Act, relying instead on cease and desist orders. This targeted application of heavy fines reflects a focus on what policymakers deemed the most critical bottlenecks (app distribution, payments).

- Commitment Procedures (Kakuyaku Tetsuzuki) (Art. 22-29): Designated providers can propose voluntary commitments to the JFTC to address competition concerns related to any of the prohibited conducts (Art. 5-9). If the JFTC approves the commitment plan, it will close the investigation without issuing orders or penalties for that specific conduct. This provides a potentially faster, less adversarial resolution path.

5. Implications and Analysis

The Smartphone Software Act is poised to have a profound impact on the mobile ecosystem in Japan and the global companies dominating it.

- For Designated Platforms (Likely Apple & Google): The Act imposes significant compliance burdens, potentially requiring substantial changes to their business models, technical architecture, and contractual terms in Japan. Key impacts include:

- Allowing competing app stores and potentially alternative payment systems could directly affect revenue streams (e.g., app store commissions).

- Mandated interoperability and data portability requirements necessitate technical adjustments and potentially reveal strategic data.

- The threat of high kachoukin for core violations (even if limited in scope) creates strong incentives for compliance in those specific areas.

- Increased scrutiny and ongoing reporting obligations to the JFTC.

- For App Developers & Competitors: The law offers potential benefits:

- More choices for app distribution beyond the incumbents' stores.

- Potential for lower payment processing fees through alternative systems.

- Fairer access to users and potentially OS functionalities.

- Reduced risk of discriminatory treatment or arbitrary rule changes.

- However, challenges may arise from ecosystem fragmentation and the need to adapt to potentially varying standards or security levels across different app stores or browsers.

- For Consumers: The intended benefits include greater choice (in apps, browsers, payment methods), potentially lower prices for digital goods and services due to increased competition, and more control over default settings and data. However, concerns have been raised (and are reflected in the Act's justification clauses) about potential risks to security and privacy if the ecosystem becomes significantly more open, requiring users to exercise greater caution.

- Comparison with EU DMA: Japan's Act shares the core philosophy of ex-ante regulation for digital gatekeepers but is narrower in scope (smartphone-specific vs. broader core platform services in DMA) and targets fewer specific practices with the highest penalties. The handling of justifications (especially security/privacy) may also differ in practice. It represents Japan tailoring the DMA concept to its perceived national priorities and market realities.

Conclusion

The Act on Promoting Competition for Specified Smartphone Software is a landmark piece of legislation marking Japan's most direct regulatory intervention into the competitive dynamics of core digital ecosystems to date. By imposing specific behavioral rules and obligations on designated dominant providers of mobile OS, app stores, browsers, and search engines, it aims to dismantle perceived anti-competitive barriers and foster a more open, innovative, and fair market environment.

Inspired by international developments like the EU's DMA but tailored to Japan's context, the Act introduces potentially powerful tools, including high administrative penalties for certain critical violations. However, its ultimate effectiveness will depend on several factors: the JFTC's approach to designation, the rigorous interpretation and enforcement of the prohibitions and obligations, the handling of justification claims (especially concerning security and privacy), and the practical impact of the high but narrowly applied penalty regime.

As the Act moves towards full implementation, likely in late 2025 or 2026, global technology companies operating in Japan, as well as app developers and other ecosystem participants, must prepare for significant changes. The law signals Japan's commitment to addressing gatekeeper power in critical digital markets and will undoubtedly reshape the competitive landscape for smartphone software and services within the country.

- Japan’s Evolving Platform Regulation Landscape: An Overview for Global Businesses

- Content Moderation and Intermediary Liability in Japan: Understanding the Revised Provider Liability Act

- Platform Power and Antitrust in Japan: Lessons from an Algorithm-Change Case

- Cabinet Office Headquarters for Digital Market Competition — Mobile Ecosystem Final Report (JP)

https://www8.cao.go.jp/digitalmarket/mobilereport_2023.html